While the Church of Ireland was the Established Church in Ireland since the time of Henry VIII, it was not the only Protestant group operating in Ireland. Methodists, in particular, had won many converts since the days when John Wesley himself had come preaching (above). However, like Catholics, breakaway and Dissenter communities were disadvantaged in comparison to the Church of Ireland.

Bandon Methodist Church, established in 1821

This privileged position, while it came with all the advantages conferred by reliable revenues, political power and access to education, was also accompanied by the constant awareness of being a minority, often an unwelcome one, and by the decadence and laxity that generations of wealth can confer.

1864 Map of the Church of Ireland Dioceses

Dr Kenneth Milne, writing in The Church of Ireland: An Illustrated History (Published by Booklink, 2013) describes the situation thusly:

. . . plurality and non-residency came to be regarded as endemic. There is evidence that there were many faithful (and often impecunious) Church of Ireland clergy, but their existence has been somewhat masked by the prevalence of ambition and negligence among many others, particularly of the higher rank.

While it was to the bishops that one would have looked to remedy the situation, they themselves were frequently non-resident, at least for long periods, preferring the amenities of Dublin (or sometimes London and Bath, for most of the more remunerative sees were given by the crown to Englishmen as part of that great web of patronage that lay at the heart of government and was the norm). Such episcopal failings were by no means peculiar to the bishops and other dignitaries of the Church of Ireland, and were common throughout Europe, but what made the Irish episcopate more vulnerable to criticism was its remoteness (in more sense than one) from the great majority of the populations, and the fact that it drew it emoluments, often very considerable indeed, from lands to which its entitlement was often in dispute. In addition, it demanded tithes paid by a resentful population who, be they Roman Catholic or Dissenter, were also encumbered with contributing towards the support of the ministry of the Church to which they gave their fealty.

The Tithe Collector – collectors were employed on behalf of the clergy and were called Proctors. They took a cut, so there was a strong incentive to collect

Catholic Emancipation in 1829 was followed by a period of intensified conflict over tithes, known as the Tithe Wars. (Tithes had been a source of great conflict forever – see Robert’s post for La Tocnaye’s observations about tithes in the 1790s.) A large anti-tithe meeting was held in Skibbereen in July 1832 and the speech made by Father Thomas Barry of Bantry was reported in full. Here are some extracts from it, reported by Richard Butler in his paper St Finbarr’s Catholic Church, Bantry: a history for Volume Three of the Journal of the Bantry Historical and Archaeological Society:

The Rev. Thomas Barry, P. P., in seconding [an anti-Tithe] resolution, announced himself as a mountaineer from Bantry, and was received with a cead mille failthe [sic], which was sufficient to affright all the proctors in the kingdom from their propriety. . . .

But (continued the Rev. Gentleman) . . . If to assist the people in their peaceful and constitutional efforts for the removal of grievances to hear the insolence of power in defence of the poor man’s rights, invariably to inculcate on the minds of my flock the most unhesitating obedience to the laws, and at the same time, to raise my voice boldly and fearlessly against injustice and oppression. If these constitute the crime of rebellion, then do I rejoice in acknowledging the justice of the charge. [tremendous cheering.]

. . . Some time since I commenced building a chapel in Bantry, which, owing to the poverty and privation of the people, I have been unable to finish, although thousands are extorted from them for the Parson and the Proctor – the Churchwarden applied to me for Church rates – I desired him to look at the Chapel, and there he would find my answer: he begged of me not to give bad example by refusing to pay, and I told him, that I was well convinced that the example which I gave in this instance was particularly edifying. – (great laughter and much cheering.) – The proctor came next, and threatened me with distraint for the amount of tithes with which he charged me, and which I must do him the justice to say he never previously demanded. I told him to commence as soon as he pleased; and so gratified did I feel at the honour which he intended for me, that I was resolved to make a holyday day for him (laughter and cheers.)

– The Rev. Gentleman sat down amidst the most enthusiastic cheering.

This meeting was but one in a series in West Cork throughout the 1830s. Patrick Hickey, in Famine in West Cork, reports on meetings in Bantry and at the foot of Mount Gabriel – meetings attended by thousands, each parish under the leadership of their priest. In Bantry, the various tradesmen of Bantry marched in procession, each trade with its own banners. On one side of the tailors’ banner was a portrait if Bishop Doyle with the inscription, ‘May our hatred of tithes be as lasting as our love for justice’ and on the other side a portrait of Daniel O’Connell. At the Mount Gabriel meeting a procession of boats came from the islands and the men of Muinter Bheara arrived under the command of Richard O’Donovan of Tullagh and many Protestants (including Methodists and the descendant of Huguenots) attended.

One of the most outspoken of the Church of Ireland community against the anti-tithe movement was Rev Robert Traill, Rector of Schull (above). In doing so he was following the example of his father, the Rev Anthony Traill, who had used a particularly brutal proctor, Joseph Baker, to collect his tithes, while he himself resided in Lisburn. Fearing, of course, the loss of his income, Rev Robert railed against the meetings, declaring that in doing so he waged war against Popery and its thousand forms of wickedness. When cholera broke out after one of the monster meetings he wrote that is was God’s punishment for the agitation stirred by the iniquity of these wicked priests. He had reason to be afraid – the rector of Timoleague had been murdered and throughout the country killings, assaults and riots had occurred. It was a challenging time to be a Church of Ireland rector. (Remember Rev Traill, by the way, and don’t cast him as a villain in this story – he will feature again for his heroic role during the famine – yet another twist in the complex role of the Protestant church in this part of Ireland.)

The battle at Carrickshock, Co Kilkenny (from Cassell’s Illustrated History of England). This confrontation over tithes resulted in several deaths and sent shock waves through the country

Eventually (see Part 2) the Tithe Wars eased, a compromise (if not a solution) was reached and outright protests ceased. Let us turn our attention now to what was happening within the Church of Ireland in matters of doctrine.

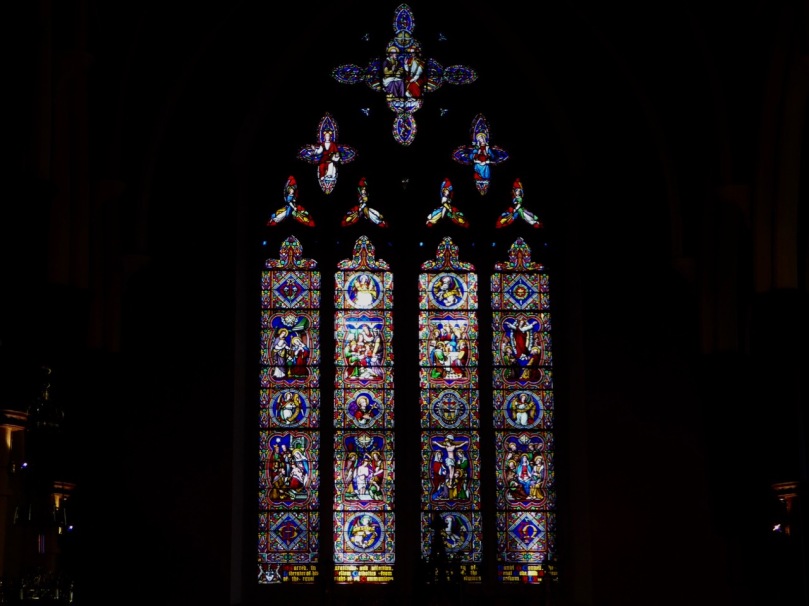

An enormous stained glass window in Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Cork is dedicated to Daniel O’Connell, The Liberator, by a grateful people

Latitudinarianism – lovely word, isn’t it? It refers to the live and let live philosophy that was generally adopted by Protestants in the 18th century. Actually a reaction against the Puritan insistence on a single form of Truth, it was sometimes called Broad Church and was a mode of thought that tolerated variations on thought and practise and sought to peacefully co-exist with other forms of worship. However, by the beginning of the nineteenth century, this emphasis on compromise and moderation was gradually being replaced with a new evangelical fervour, leading to a movement known as the Second Reformation.

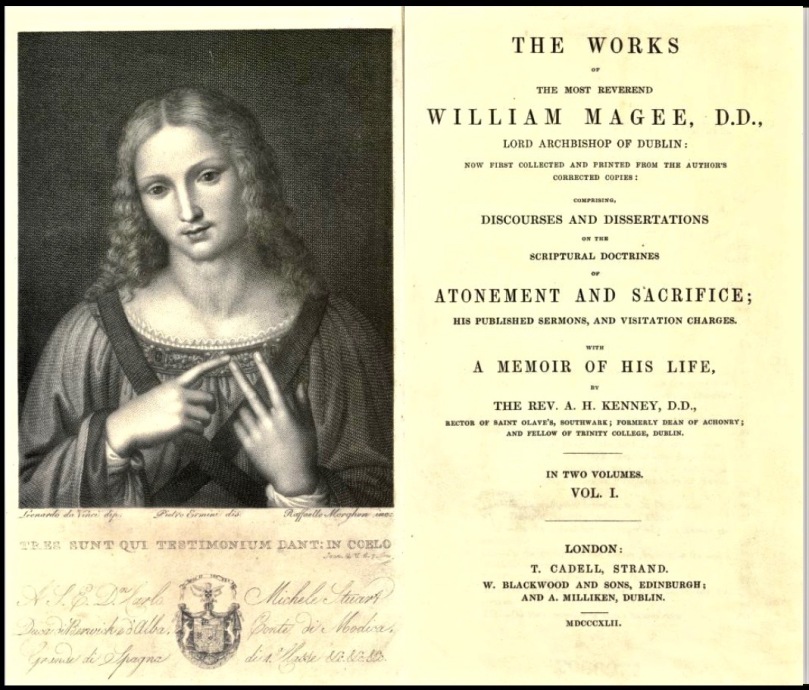

This movement, it is often said, was kick-started in Ireland by William Magee, Archbishop of Dublin and fervently committed to the Second Reformation. He gave a firebrand sermon upon his inauguration in 1822 in which he accused the Catholics and the Methodists thus:

. . . the one possessing a church without which we can call a religion, and the other possessing a religion without which we can call a church: the one so blindly enslaved as to suppose infallible ecclesiastical authority, as not to seek in the word of God a reason for the faith they possess; the other so confident in the infallibility of their individual judgment as to the reasons of their faith that they deem it their duty to resist all authority in matters of religion. We, my Brethren, are to keep free of both extremes, and holding the Scriptures as our great charge, whilst we maintain the liberty with which Christ has made us free, we are to submit ourselves to the authority to which he has made us subject.

In this sermon, which created a furore at the time, he was essentially giving voice to prevailing Protestant opinion at the time regarding the other churches, and also to the claim of the Church of Ireland to be the only national church. It is important to note here that the Church of Ireland considered then, as it does to this day, that far from being an imported or imposed religion, it was, and remains the only true successor of the original faith of the Irish. This was first argued by James Ussher (portrait below by James Lely) in the seventeenth century.

The Church of Ireland, Ussher said, was not created by Henry VIII, but that St Patrick was Protestant in his theology and that the real problem was the interference of the Pope. (Ussher, by the way, is the same prelate who established that the world is only 6000 years old, another statement that continues to resonate in fundamentalist circles – but that’s another story.) In this origin story, it was important to “rescue” the true Irish church from Rome and restore it to the vision of St Patrick. The current catechism on the St Patrick’s Cathedral website continues this tradition. To the question “Did the Church of Ireland begin at the Reformation?” the answer is “No – the Church of Ireland is that part of the Irish Church which was influenced by the Reformation, and has its origins on the early Celtic Church of St Patrick.”

William Magee bust in Trinity College

Magee’s assertions were sincerely held positions. Although a cultured and erudite man, and tolerant in many respects, he was violently opposed to Catholic Emancipation, seeing the conversion of Romanists to Protestantism as a far better option both for them and for the country. His sermon effectively marked the end of any leftover latitudinarian attitudes in Ireland and heralded the arrival of a new era for the church of Ireland, in which educational, evangelical and proselytising activities were seen as essential. Next week we will see what effect those activities had on the already deepening divide between Ireland’s faith communities in the pre-famine period.

St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin – along with the position of being the Established Church, all the ancient churches became the property of the Church of Ireland, including this one. Magee delivered his famous sermon here

This link will take you to the complete series, Part 1 to Part 7

Just catching up on weeks of blogs by each of you.. Learned so much from this series. Excellent research and photos–as always! Best to you and Robert.

LikeLike

Thank you for the fascinating story of one aspect of life on the Mizen; have passed by the church several times. This all helps to understand some of my own family background.

(My gtx4 grandfather was Rev. Paul Limrick, vicar and rector of Kilmoe and Schull (1723-1754).

Brian Limrick

LikeLike

What a tangled web of faith, blindness, bigotry, poverty and hellfire!! I do like the sound of the mountaineering Rev Thomas Barry though!

LikeLike

Richard Butler’s paper on St Finbarr’s In Bantry is full of such gems.

LikeLike

I am learning so much from this series. Doesn’t improve my attitude towards the ‘organised madness’ of religion though!

LikeLike

Thanks – it seems like it’s taking a long time to tell the story, but we’ll get there in the end.

LikeLike

Finola, did you know that my father’s family consisted of Methodists and Huguenots from the environs of Cork. I was brought up as a Methodist and left it as soon as I could!

LikeLike

Didn’t know that – I assumed it was C of I. I wonder if he went to that Bandon church. It’s quite beautiful inside.

LikeLike

My grandfather, James Orr Burchill, was Baptised March 14, 1864 by Rev. Wallace McMullen at the Methodist Church in Ballymodan, Bandon, Co. Cork, Ireland.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So that IS the same church as pictured above, in which your Grandfather was baptised! He went on to have a son, John Burchill, who married my mother’s first cousin, Hilda Brabazon – that’s how come you and I are second cousins. It’s probably a safe bet that your father attended that church as a child.

LikeLike