Today I am looking at what happened to Teampall na mBocht when the Catholics finally got the resources together to win back Fisher’s converts. As we saw in the last post, the Rev William Allen Fisher built Teampall na mBocht (above) with money raised through his own efforts, confining the work to the poorest labourers. There is no evidence that he made employment on this project conditional on conversion, and his own accounts quantify payments to Catholics as well as Protestants (going by the evidence of last names, which can, of course, be misleading).

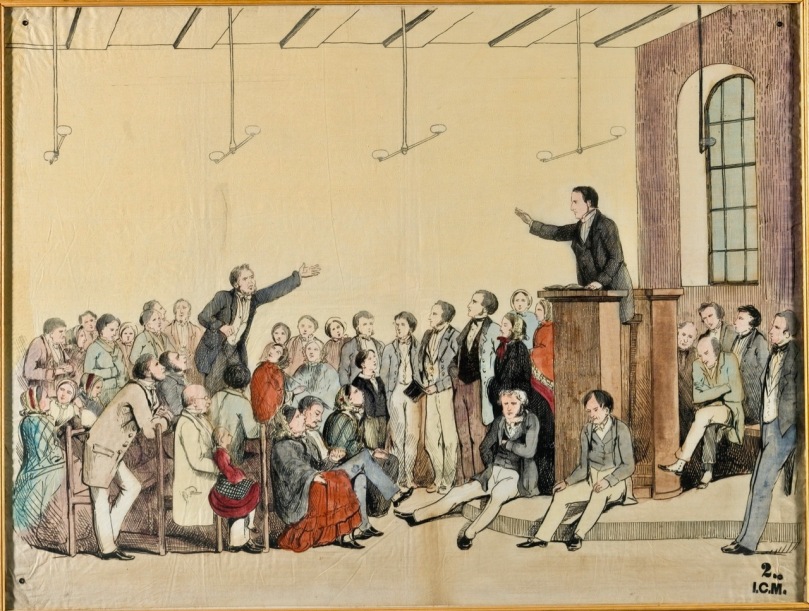

Reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Ireland (with permission) from a collection of prints by the Irish Church Missions to Roman Catholics. The notes accompanying the image say: This image shows a Protestant clergyman standing at a pulpit with his right arm raised in anger while arguing with a Roman Catholic clergyman in the audience. Audience is divided into 2 groups determined by features. Those seated have more prominent features with upturned noses and those standing have more stern features with straight noses

However, he also supplied food to the Christian missionary schools in the area, the enrolments of which surged accordingly, and he enthusiastically welcomed those who wished to confess and be converted: the number of Church of Ireland adherents rose dramatically in the Goleen area during this period. He denied all charges that he ‘bought’ such conversions. The activities of a clergyman who also happened to be a large landlord using relief funds to build a Protestant church and fund Protestant mission schools, even if by doing so he saved many from starvation, were always going to excite odium within the minds of his Catholic counterparts.

Alexander Dallas, founder of the Irish Church Missions to Roman Catholics Photo from Archive.org

The Protestant Crusade, with its colonies and schools and aggressive proselytising, had reached its zenith in the period leading up to and during the famine. Led by men like Alexander Dallas of the Irish Church Missions, or Bishop Robert Daly of Cashel, it never succeeded in winning the numbers of converts that its proponents and funders hoped for. What it did, in fact, was to drive a sectarian wedge deep into the heart of Irish society and create a legacy of bitterness and distrust.

Lord John George de la Poer Beresford, every inch the aristocratic Lord Bishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland

Moderate and liberal Church of Ireland leaders such as Archbishops Whately of Dublin and Beresford of Armagh, tried to curb the worst excesses of the movement, worrying that that The ICM was doing “Irreparable mischief to the Church in Ireland”. While they both deplored the ‘Romish’ religion they hoped for conversions through Irish Catholics seeing what a model of bible-based virtue looked like, not by means of radical evangelical activities and proselytising.

Richard Whately, Archbishop of Dublin, a complex and possibly misunderstood prelate

A Catholic backlash was inevitable and when it came it was as complete and heavy-handed as it was possible to be. Seeing the situation, and the number of converts in Goleen and Toormore, Bishop William Delany of Cork sent in the big guns, in the form of Fr John Murphy, AKA The Black Eagle of the North.

William Delaney’s rather magnificent statue in Cork. Note the Papal Insignia

Wait – the what? Yes, you heard me right! A scion of the famous and wealthy Catholic merchants, distillers and brewers (themselves accused of exporting grain during the Famine by none other than Fr Matthew) John James Murphy was the stuff of legend. Here’s a quote in full from one account (based on a well researched biographical sketch), because, well, you can’t make this stuff up.

The scene changes to a clearing in the virgin forests of Canada. There a French-Canadian priest has pitched his camp. He has no flour to make Hosts for the Holy Sacrifice and then down the little stream that bordered the clearing there drifted a birch-bark canoe paddled by an Indian. He shared his flour with the priest who was surprised at the soft cadences of the Indian’s English. And no wonder, for the Indian was born not on the banks of the St. Lawrence but on the banks of the Cork Lee. It was John James Murphy, one time an officer in the navy, now a hunter in Canada. In the course of his journeyings the Corkman had fallen in with a tribe of Red Indians and had thrown in his lot with them. They initiated him into their tribe, crowned him with feathers and dressed him in all the accoutrements of an Indian brave. To them and to all of the Five Nations he was known as the Black Eagle of the North.

In Black Eagle’s wanderings through the forests he came one day upon a green glade in the centre of which was a statue of the Blessed Virgin. And there in that silent glade there came back to him the faith and the teaching of his childhood. Perhaps the spirit of some martyred Jesuit was hovering around that neglected shrine.

So he returned to his tribe, washed off his war paint, relinquished his chieftain’s features and started off on a long trek, down the Hudson river, across the broad Atlantic, over the European continent to Rome, to commence his studies for the priesthood.

This account, by the way, omits to mention that in Murphy’s own words he also “dismissed his squaws.” The language, by today’s standards, is shudderingly horrifying throughout, isn’t it?

Murphy (above, illustration from Patrick Hickey’s Famine in West Cork) arrived dressed in black, wearing a tall black hat and flowing black cloak, and riding an enormous black ‘charger.’ He brought supplies of meal for the schoolchildren in the national school, took lodgings in Goleen, and set about sniffing out the converts. He marched them to Teampall na mBocht, mounted the wall, and proceeded to give a fiery sermon exhorting them to return to their true faith and insisting they recant at Fisher’s gate. His appearance and eloquence was electrifying and soon had the desired effect.

Interior of St Peter and Paul Church in Cork City, established and partly built by John Murphy’s considerable inherited wealth

Reinforcements arrived shortly thereafter in the form of a Vincentian mission. These missions, in which a group of priests from particular orders such as the Vincentians or the Redemptorists, would descend upon a town and preach every night for a week, were a staple of my young life. This one was reported to be a great success. Fr Hickey quotes from a contemporary report:

Our mission in West Schull (Kilmoe). . . is doing much good. A great number of the poor who were perverted in the time of the famine by relief given for that purpose by the Protestants, have returned already. The chapels, even in weekdays, are not able to contain the congregation and the confessional is crowded far beyond the power of our confreres to accomplish its work.

In fact, the famine was not over, and the Vincentians brought more than The Word of God (and the Fear of God) with them – they also distributed great quantities of food relief and some cash, both to individual families and to the schools. They established a chapter of the Society of St Vincent de Paul and the members busied themselves visiting the poor and distributing supplies. Fr Hickey says:

Food was now being used by the Catholic Church in order to hold on to its flock and win back the lost sheep. Did hunger tempt them to stray in the first instance? Were they now coming back because they were simply going to the church which would give them the most food, as some of them had bluntly told Fr Laurence O’Sullivan?

St Vincent de Paul. Most Irish people today recognise the Society of St Vincent de Paul as an active Catholic charitable organisation. The Vincentians, on the other hand, have declined in numbers to the extent that their Cork headquarters had to close for lack of vocations

Revs Fisher, Triphook (successor to Dr Traill), Donovan and Crossthwaite wrote a published statement which accused John Murphy and the Vincentians of failing to come during the horrors of famine and arriving only now in the harvest ‘to propagate Romanism’.

Fisher’s church in Goleen, now in use as a sail-making space. His pulpit would have been an important part of the church furnishings and I am pleased it has survived

It was a telling counter-accusation to the charges of Church of Ireland souperism, but in any case the heyday of the radical and fundamentalist evangelicals was nearing an end. A new era was dawning for the Irish, that of the Ultramontane Catholicism of Cardinal Cullen – the ethos that would drive Irish Catholicism for the next one hundred and fifty years.

This photograph is captioned Late nineteenth-century evangelical preacher addressing a crowd under police protection, and is credited to Michael Tutty

Although I had hoped to finish this series with this post, I have learned so much now about the religious legacy of this extraordinary time in Irish history that I find myself unable to resist one final episode in the saga. In my next and last (I promise!) post in this series, I will endeavour to relate how the foundations of the kind of Catholicism I grew up with were laid down upon the contested ground of Teampall na mBocht and on the battle for the hearts of souls of the people of Ireland that such places epitomised. I shall also attempt to draw some personal conclusions from what I have learned, and to share with you some of the excellent resources I have used in this series.

Reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Ireland (with permission) from a collection of prints by the Irish Church Missions to Roman Catholics. This print is captioned Two preachers standing in a street preaching to an audience. In the background a rabble sings, dances and jeers. The notes given for this image in the NLI collections are: The differences between those converted to Evangelicism and the “unconverted” Roman Catholics are emphasised in this image. The captivated audience surrounding the preachers are dressed well whereas the rabble causing trouble behind them are badly dressed with the stereotypical Irish look about them

This link will take you to the complete series, Part 1 to Part 7

Very enjoyable article, Finola. As you say, you could not make this up! I look forward to your next post.

LikeLike

Thanks, Pat. I’m enjoying the reading.

LikeLike

Good Heavens full of incredible characters today, the wildly eccentric Black Eagle of the North, the pompadourish Lord Bishop of Armagh and the rather kindly and thoughtful looking Archbishop Whately. They don’t make them like this any more – do they? What a riveting story.

LikeLike

I lived the description of his horse as a ‘charger’.

LikeLike

Hi Finola. As always, a wonderful post – many thanks. The description of a horse as a “charger” appears in the song “The Galloping Major” which was written in the early 1900’s. I heard it sung from the stage of the Cork Opera House in the 70’s.

LikeLike