There are places on this island that seep into your soul. You come away with a sense of having visited another world, of having passed through a portal and been lucky enough to come back to tell the tale. Such a place is Monaincha in Tipperary.

We made this trip because I was studying Irish Romanesque architecture and Monaincha is a fine example, but we had no real idea what to expect and it caught us off guard. An ancient signpost directed us down a rough track through the trees and then by foot across the fields. Our first glimpse was of what looked like an island in the middle of flat land.

We weren’t wrong – this had been an island, called Inchanambeo (Incha na mBeó) which translates as Island of the Living. Curious name, but of course, this being Ireland, there’s a story to it. Here it is from Dúchas, the School’s Folklore Collection, collected by a 12 year old in the 1930s:

On this lake were two islands; the Island of the living which was the smaller of the two was a place to where saints went who wanted to live alone – with God. It was called the Island of the Living because it was said that no one could die who went on this island. Of course this is not to say that their bodies could not die – it meant that their souls could not die, because Our Lord said “He that eateth of this bread shall live for ever”. No woman could go on the large island because she would die. This was often experimented, when men brought female animals on the island but they dropped dead the moment their feet touched the island.

Hmmm – as a woman, perhaps I did indeed go through some kind of portal, since I managed to live through the experience. That explains the Otherworldly feeling!

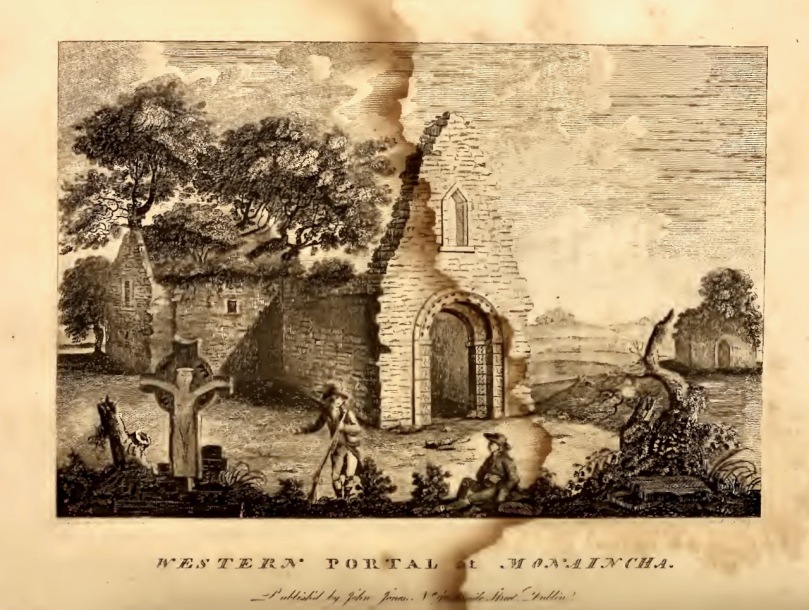

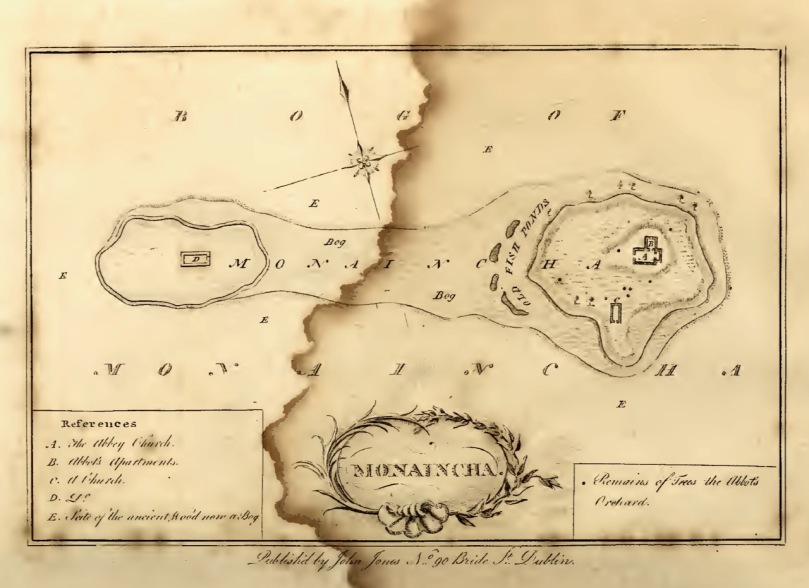

The top image and this one are from Ledwich’s Antiquities of Ireland, published in 1790. His map clearly shows that both islands were still there at that time, with a building still in place on the small island, while the first illustration shows the second building on the large island, no longer there

For this and more Duchas stories about Monaincha, go to this link on the Dúchas website. You will see that Cromwell sacked the monastery, that the woman who gave away the monks’ location was turned to stone along with her cake of bread, that the lake contains hidden treasure, that the water if used improperly would not boil, that many miracles were associated with the saints who lived on Monaincha, and that a white lady roamed the area until banished by a priest but not before she left her mark on him (read the story).

And here it is – the cake of bread that was turned to stone

One of those saints was St Canice, who came on retreat to this sacred spot:

He did not let anyone know where he was but he got letters and messages each day by means of the Garnawn Bawn. This was the White Horse which passed each day without a guide from Agherloe to Monahinche.

St Canice (second from right) in good company with Sts Patrick, Brigid and Eugene. He’s holding his cathedral. The window is in St Eugene’s church in Derry

But it was St Cronan who built the church:

St Cronan and his monks sought a place where they could build a residence. They proceeded to the parish of Bourney to a place called Bogawn but looking towards Monahincha they saw the sun shining on it and so fixed the site of their future home on Monahincha. St Cronan lived for a long time in Monahincha and while he was there he prayed a great deal and performed many miracles.

For a more academic history of Monaincha we turn to the bible of all things Romanesque, the Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture. From it we learn that:

Originally known as Inis Loch Cré, the name Mona Incha was only given to the site in the in later centuries. The earliest monastery here was founded by St Cainneach of Aghaboe in the 7thc as a hermitic settlement. Column Mac Fergus died on Inis CrÈ in 788 as did Elarius, anchorite and scribe, in 807. The latter was St Elair, or Hilary who was patron of the monastery in which the Culdees were instituted in around the 10thc. In 902 Flaithbertach, King of Cashel, came here on pilgrimage. An Augustinian community was established at Mona Incha during the mid-12thc.

In 1397 the monastery, containing a prior and eight canons, was taken under the Pope’s protection and released from paying Episcopal dues because of its extreme poverty. At about the same time the Book of Ballymote described Mona Incha as the 31st wonder of the world! In c.1485 the prior and convent finally moved to Holy Cross at Corbally, as the canons found the vapours from the marshes surrounding the island unhealthy. Following the Dissolution the church was used as a penal chapel.

Much of this is based on the erudition and scholarship of Harold Leask, whose three volume book Irish Churches and Monastic Buildings has a section on Monaincha. He also authored, along with C MacNeil, an article in the Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland which is a very comprehensive account of all that can be gleaned from annals and hagiographies of the history of Monaincha*.

Leask’s plan of the ruins at Monaincha

He cites Gerald Barry’s (better known as Giraldus Cambrensis) Topographia Hibernia (written in 1188), to show how ancient is the tradition of the Isle of the Living.

There is, he says, a lake in North Munster containing two islands, a greater and a less. The greater has a church of an ancient religious order and the less has a chapel served by a few celibates whom they call Celicolae or Colidei [Culdees – an ancient hermetic order]. No woman or animal of the female sex could enter the greater island without dying immediately. This has been put to the proof many times by means of dogs, cats, and other animals of that sex, which have often been brought to it as a test, and have died at once. As regards the birds of the district, it is wonderful how, when the males settle at random on the bushes of the islands the hen birds fly past and leave the males there and avoid that island like a plague, as if well aware of its natural power. No one ever died or could die in the smaller island, whence it is called the Isle of the Living; yet from time to time persons are afflicted with deadly ailments and suffer agonies to their last breath. When they feel there is no longer any hope of really living, and by the increase of their disease they are in the end so distressed that they would rather dies outright than continue in living death, they have themselves brought at last in a boat to the greater island, and they give up the ghost as soon as they touch the land.

Leask and MacNeill go on to state that the place had been the site of pilgrimage formerly and some stations were still visible in 1848, and that the proprietor of the place had drained the lake in the 1820s or so and forbade all access to the church either for burial or pilgrimage, destroyed tombstones and erected round the church a circular mound, composed, the people say, of the mortal remains of the hundred generations deposited in that favourite churchyard.

What was once the larger island (there is no sign now of a second one) is still, as Leask described in the 1920s, a circular raised platform, due to the draining of the surrounding land, but there is still very much a sense of travelling across an open expanse to get to it. Marooned in the middle of a large field, the island is visible as a group of very tall trees and it’s not until you get close to it that you begin to see the structures.

As with many such sites in Ireland, the graveyard surrounding the ruined church, despite what Leask asserts, appears to be still intact. This adds to the reverential feeling of the place, as do the enormous trees, which must be hundreds of years old. A partly reconstructed high cross stands at the entrance – Robert wrote about this one in his post Fading Treasures.

The church is a Romanesque gem. (For more about Irish Romanesque architecture, I have provided a list of previous posts at the bottom of this post.) Dating to the twelfth century, it is a nave and chancel church, fairly typical of the time. There is a later addition on the north side, referred to as a sacristy in Leask’s plan. The sacristy is shown in the Ledwich drawing (first image at top of post), which dates from the 1790s. As could be seen also in Ledwich’s site map, there was much more to the whole site than there is now.

The main door has three (or four, depending on who’s counting) orders, each one carved in the Romanesque fashion with chevrons, zigzags, pellets, floral motifs within lozenges, and some scrollwork. Although weathered, most of the the carvings are still clear to see and very attractive. There are hints of animal heads but they are difficult to discern.

One of the pleasure of Leask’s accounts is his wonderful line drawings. In his plan of the door M stands for ‘modern’ – the doorway was repaired, probably by the Office of Public Works, at some time before his visit

The door is much plainer on the inside, with only one order and no visible carvings. This is normal in Romanesque buildings – the difference between the elaborate entrance and the unadorned exit is often quite startling.

Above the door is a narrow window that was modified in the 15th century by adding an ogee head to the top of the frame

Inside, the nave has some fine windows, although not all of them bear scrutiny as original to the 12th century period of construction.

Only the smallest window is recognisably Romanesque

But it is the chancel arch that dominates the space. It separates the small chancel – the area where the altar would have been and mass would have been celebrated – from the nave where the monks and the faithful would have gathered.

Photograph taken in 2017 and drawing done in 1790. In Ledwich’s drawing the entry to the vaulted sacristy (probably 15th century) is on the left

The arch is characteristic – three orders with carvings on both the arch and on the jambs, which are slightly inclined. The capitals are scalloped. The decoration is similar to that on the main door, indicating it was probably carved at the same time and maybe by the same hands.

The experts at the Corpus compare the carvings to the Nun’s Chapel at Clonmacnoise and say, The squared patrae on the outer order of the doorway find an almost identical parallel at Clonfert (Galway), although at Clonfert the floral decoration of the motif does not vary. The closest comparisons to the chevron ornament are found at Killaloe and Tuamgraney (Clare). These comparisons suggest a construction date of c.1180, perhaps to coincide with the establishment of the Augustinian canons at the site.

Another view of the chancel arch, this time from Archiseek

The ground floor of the sacristy is vaulted and contains tombs. This one memorialises A Sincere Friend and An Humble Christian and dates from 1832

The vaulted sacristy was added in the 15th century (Leask comments on the inferiority of its construction) and several other later modifications are visible to windows. There are now no other buildings on the island, and of course no trace of the second island or of any other structures that one would associate with a 12th century monastic settlement, such as a round tower or an enclosing circular wall.

No matter – what is there is magical. We spent so long at Monaincha that the light was declining as we were leaving. It added to the atmospheric feeling of the place, and a sense that we were travelling back to ordinary life from the storied Isle of the Living.

In this, I share the emotion with Harold Leask, whose love of this site shines out in his writing. In his book he states, Perhaps no other church ruin in Ireland is so attractive in site, interesting detail and appearance. . . In the Architectural Notes that follow the JRSAI history he writes, I first saw it. . . upon the afternoon of a summer, its walls golden in the rays of the westering sun, the little green mound with its circling wall and groups of beech trees forming a perfect setting in the level bogland, bright with ragweed and and bordered in the distance by woods. The whole effect was very suggestive of a Petrie water-colour sketch, with just that delicacy and precision which is the great charm of his work.

Leask may have been thinking of this very sketch by our old friend George Victor Du Noyer from a drawing by Petrie. It is marked ‘unfinished’ and indeed the sacristy is entirely missing**

*McNeill, C., and Harold G. Leask. “Monaincha, Co. Tipperary. Historical Notes.” The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, vol. 10, no. 1, 1920, pp. 19–35. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25514550. Accessed 16 Feb. 2020

**George Victor Du Noyer, “Ideal Irish Church from a colour drawing by Geo: Petrie. Monaincha. Unfinished,” Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, accessed February 16, 2020

More about Irish Romanesque Architecture:

Irish Romanesque – an Introduction

Cormac’s Chapel: The Jewel in the Crown (Part 1)

Thank

You for your very interesting article. I live only a few miles from there and have visited it quite a few times. I feel it has its own “energy” – that it is protected.

LikeLike

How nice to be able to go there whenever you want!

LikeLike

An astonishing and wondrous place, happily ignored by the modern world. I wonder has anyone poked about in search of the ruins on the smaller island in recent times?

LikeLike

Yes, I wonder that too.

LikeLike

Well done on this article, its a great place and you have given it a very worthy digital overview 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks, Sean – glad you liked it.

LikeLike

Fascinating stories, and fine, evocative, images that make me want to visit for myself,

John

LikeLike

Thanks, John – for your next trip?

LikeLike

Wonderful text and photos! (Stephanie Christelow)

LikeLike

Thanks, Stephanie – right down your alley!

LikeLike

What a magical spot – it always pays to follow ancient signposts. You were living dangerously though! Great photographs and the drawings too are very attractive.

LikeLike

Brigid or Gobnait must have been looking out for me.

LikeLike

Absolutely fascinating – had never heard of it Paul

On Sun, 16 Feb 2020 at 23:07, Roaringwater Journal wrote:

> Finola posted: ” There are places on this island that seep into your soul. > You come away with a sense of having visited another world, of having > passed through a portal and been lucky enough to come back to tell the > tale. Such a place is Monaincha in Tipperary. W” >

LikeLike

On your list to visit now, Paul?

LikeLike