Karen Minihan has spent the last two years seeking out the forgotten stories of West Cork women who played an active role in the founding our our state. She has compiled thirteen of these stories into a compelling book – Extraordinary, Ordinary Women: Untold Stories from the Founding of the State. This book has opened my eyes to the courage and commitment of young (and not so young) women who took on dangerous roles in the War of Independence and the Civil War. Most did so as members of Cumann na mBan (the Women’s Company – the word Cumann actually means friendship), founded as an auxiliary to the IRA. This RTE piece is a good introduction to what the Cumann was all about, and includes an interview with Leslie Price, one of the women quoted in this book. Cumann na mBan, famously, was particularly well organised in West Cork and these women did everything to support the war against British occupation.

Karen (centre) with her mother and Conor Nelligan, Cork County Heritage Officer at the book launch

The book was launched on Friday at Uillinn (West Cork Arts centre) in Skibbereen, with a talk by Maura Leane (below), Professor of Applied Social Studies at UCC. She said:

Reading through the stories, I felt like I was watching an old, grainy, movie reel. Scenes were spooling out in my mind, providing beguiling insights into the history of the countryside around us, and into the activities that dominated the lives of many people living here, between 1915 and 1923, a time when West Cork, along with the rest of the country, was an active war zone. . . .It subtly shifts the spotlight of history, to pick out scenes that conjure up time and place, a local landscape, the atmosphere, and most importantly, a set of women characters. Characters, who have remained in the shadows, while attention was paid to the male heroes whose stories dominate our understanding of the period.

The stories are of women who were full of courage, spirit, skill and cleverness. The war would have been impossible without them – they scouted, carried dispatches, concealed and transported arms, nursed wounded men, raised money, sent essential supplies (like cigarettes!) to prisoners, passed on intelligence, cooked, sewed (many, many haversacks) and laundered for men on the run. They learned to handle firearms and to do first aid. They looked after the farms while their brothers were off with their Flying Columns. They cycled for miles through dark country roads to raise alarms or deliver messages.

May Hickey lived in Skeaghnore – that’s her above in later life, not looking at all like the daring young woman revealed in her stories. They had a secret room where they hid men on the run – theirs being a ‘safe house’. May found herself many an evening cleaning rifles from the stashes she maintained in various hedges and ditches in the area. Also, “gelignite, tonite and detonators were given to me on various occasions to keep dry and often I was ordered to dry gelignite near the fire which was damp after the remainder being used for explosive purposes.”

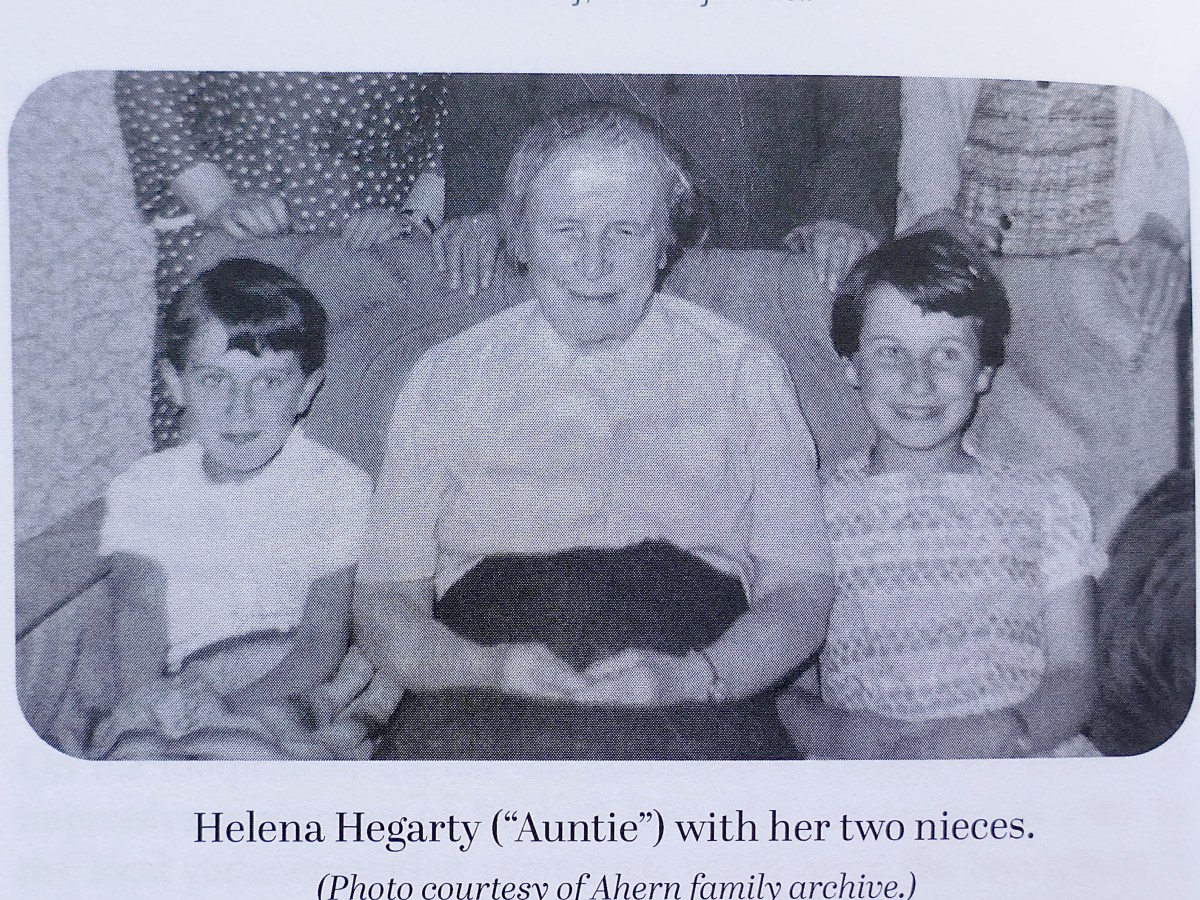

Helena Hegarty was the Matron of the Schull workhouse (above and below, as it is now). Incredibly courageous, she used her place of work to harbour IRA men and tend to the wounded. She even kept a British spy in the workhouse under lock and key for several weeks. She trained other women in first aid, and set up field hospitals. According to one account “she carried out her duties conscientiously and fearlessly.”

Having been given advance notice that the workhouse would be burned, she got out all the inmates and anything that could be saved. Because the British Military barracks in Schull was being attacked at the same time, she and her charges were under rifle and machine gun fire as they sheltered on the roads outside the workhouse. A recurring motif in the book is that few people knew of the heroism of the women who are portrayed. Below is Schull main street today – Helena Hegarty, warm and gentle and loved by all, ran a shop about where Brosnan’s Centra is now, after she was put out of work by the burning of the workhouse. She was known as Auntie by a generation of Schull children and their parents, who had no idea what she had done.

And in return the women were harassed by the Black and Tans and the RIC. Some women were roughed up and their hair was cut – it was called ‘bobbing’ and was a potent mark of punishment, used by all sides. They were threatened with having their house burned – they lived in fear but carried on. It took its toll – after Mary Ellen McLean’s brother, Michael John, was killed by the Black and Tans with appalling cruelty, she was ‘never the same.’ The memorial to her brother in Lowertown, (below), now occupies the spot where her post office was once the hub of intelligence for the region.

Most upsetting to us, as we look back from our present vantage point, is that their roles were undervalued. While heaped with praise both in the Bureau of Military History accounts of their deeds and in the Pension applications, they were routinely denied pensions by the (all-male) board, had their service downplayed and, where they were awarded a pension, were assigned to the lowest grade – E level. (Read more about that here.) Helena Hegarty was one such woman, awarded an E grade pension, despite the emphatic support by local IRA commanders for the work she had done

Karen includes the case of Bridget Noble, murdered by the IRA because she was a observed to be entering the RIC barracks. She had previously been bobbed and had lodged a complaint against the men who forced this on her, thus earning the ‘informer’ label. A thoroughly researched book by Sean Boyne (see his talk to the West Cork History Festival) has documented this case of the ‘disappeared’ woman of the Beara Peninsula.

A Cumann na mBan pin – note the centrality of the rifle

At the launch, Maura Leane summed up Karen’s work thus:

By inviting us as readers to engage with Bridget’s story, Karen pulls us, uncompromisingly, into the trauma and the violence and the highly emotive reality of this period of war, in our own localities. And when this period was over, and everyone had to start the journey of living together again, side by side, and in common cause, this trauma had to be set aside. The memories had to be put away, the stories had to be left untold. And so, this time was rendered silent. And this is why Karen’s work here, is so important. Because what Karen has done is to gently and skilfully evoke voices and emotions from this troubled time. She has storied these voices and brought forth war time memories, in all their complexity and in all their nuances. And most importantly of all, she has brought into relief the feelings and the emotional resonance that is embedded in accounts of the past.

Sullivan’s Toy Shop was once the home and business of Rose O’Connell, one of the extraordinary, ordinary women

At the launch, Karen enacted a short play based on the chapter on Rose O’Connell. Poignantly, the shop where the action took place could be seen from the room, and some of her descendants were at the event. Karen’s book is available at all good West Cork Bookstores but if you’re not lucky enough to live here you can order it from Schull’s wonderful Worm Books (thewormbookshop@gmail.com).

Fair play to Karen for highlighting these remarkable women. Though Pearse and Connolly constantly espoused gender equality, the role of women in the rising (particularly in 1916) was largely constrained to making tea, dressing wounds and running errands. The actions of the Military Pensions board doesn’t surprise me a bit. Any excuse to reject or downgrade an application was used.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Er – I don’t think Markievicz was making tea…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I attended the launch at the Arts Centre …. well done Karen

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wasn’t it lovely, Brigid!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What incredible women – I’m very glad that these stories are being told.

LikeLike

Yes – total bad-asses.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was a very difficult time in our country.

LikeLike

Yes – although some of the women saw it as exciting and the best time of their life as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I look forward to reading the book.

LikeLiked by 2 people

So wonderful to have these stories told!!

LikeLike

Your kind of history, Carol!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That looks like a remarkable and timely book, well done Karen. I will be purchasing a copy.

LikeLike

Well worth the money.

LikeLike