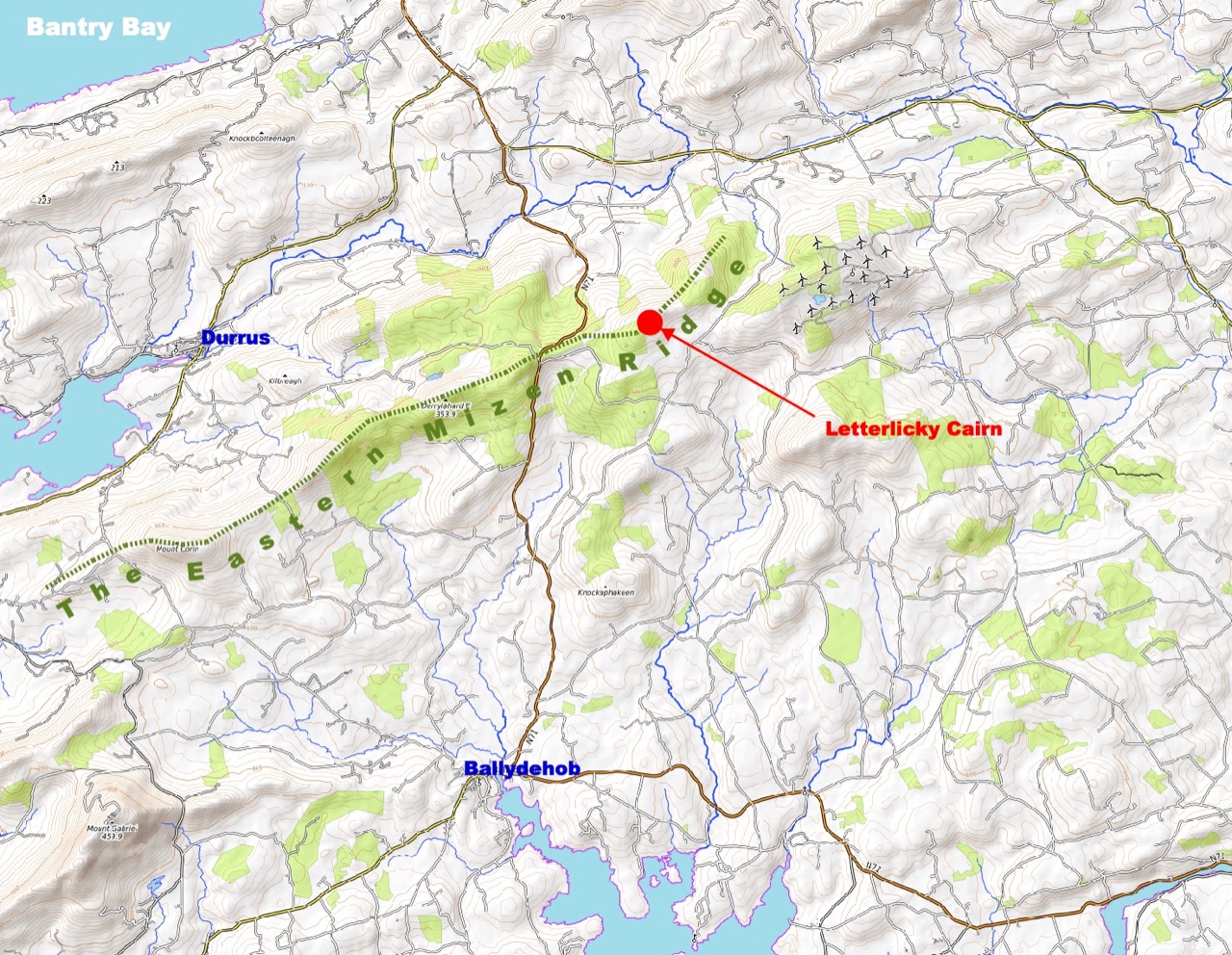

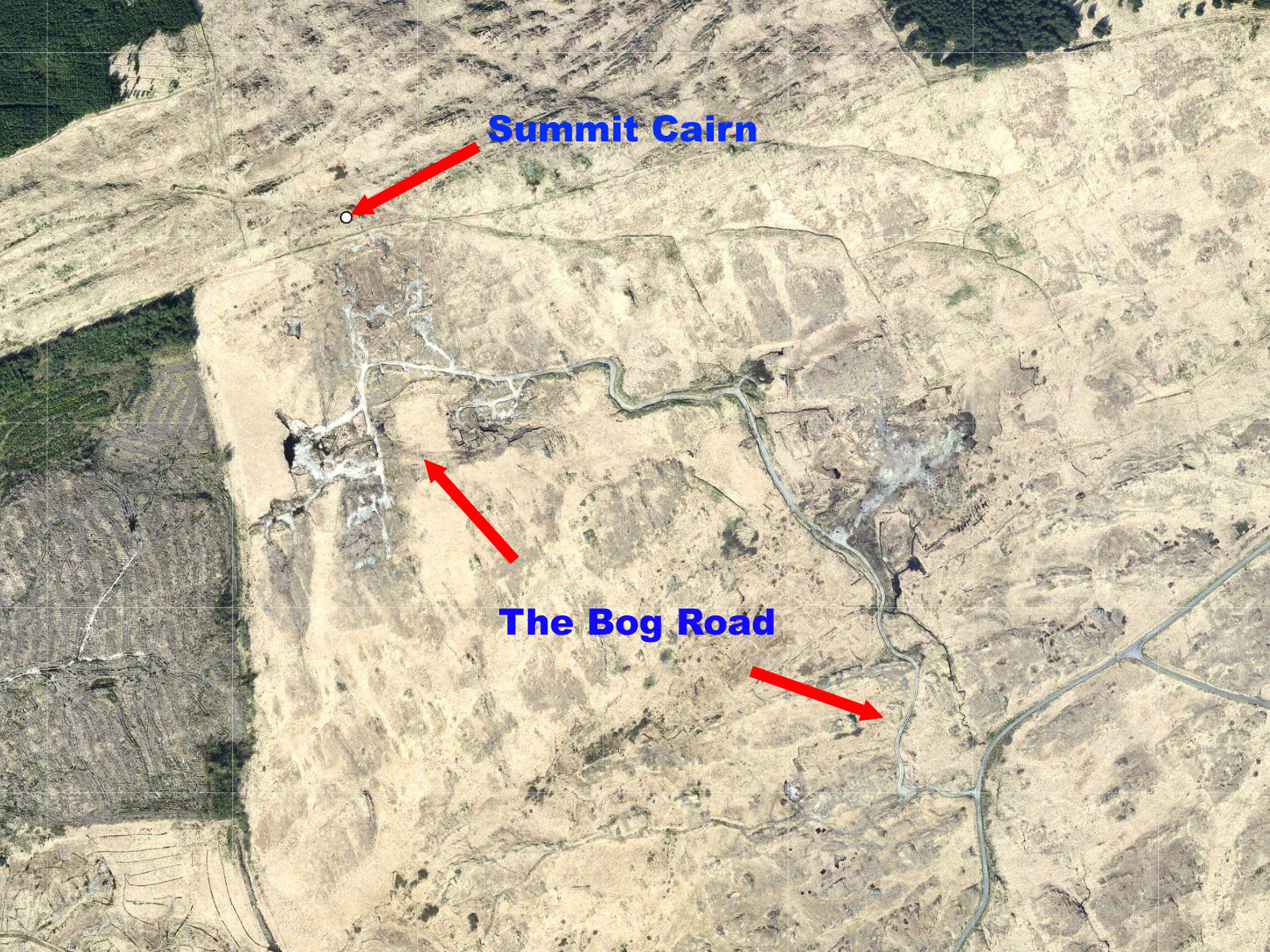

Today there is a story to tell, with lots of connections to the West of Ireland – and our own Ballydehob! That’s Levis’s Corner Bar, below, one of the village’s fine hostelries: try them all if you visit. Levis’s is known for its musical events but also for its traditional appearance inside. Look at the photo of the Irish music session (you’ll see me bottom left playing concertina) – that was taken a few years ago, before Covid; we are still waiting for those good times to return. On the wall behind the players you can catch a glimpse of a painting of men with pints and pipes.

There’s a better view of the painting, above. When I first saw it – very many years ago now – I knew immediately that it was based on a photograph that had been taken by Tómás Ó Muicheartaigh – an Irish cultural hero who spent most of his life documenting traditional life, mainly in the western counties. He lived through the founding of the Irish Free State and was an enthusiastic proponent of the Irish language. This sketch portrait of him is by Seán O’Sullivan, a friend and compatriot:

Way back in the 1970s my then wife and I ran a small bookshop in a Devon market town, specialising in folklore and traditional life. It had a substantial section on Ireland, and Irish culture. We stocked a recently-published volume (1970) celebrating the work of Ó Muicheartaigh, and I very soon had to sell myself a copy, as it is a superb record of mainly rural life in Ireland during the early twentieth century. I have it to this day – of course.

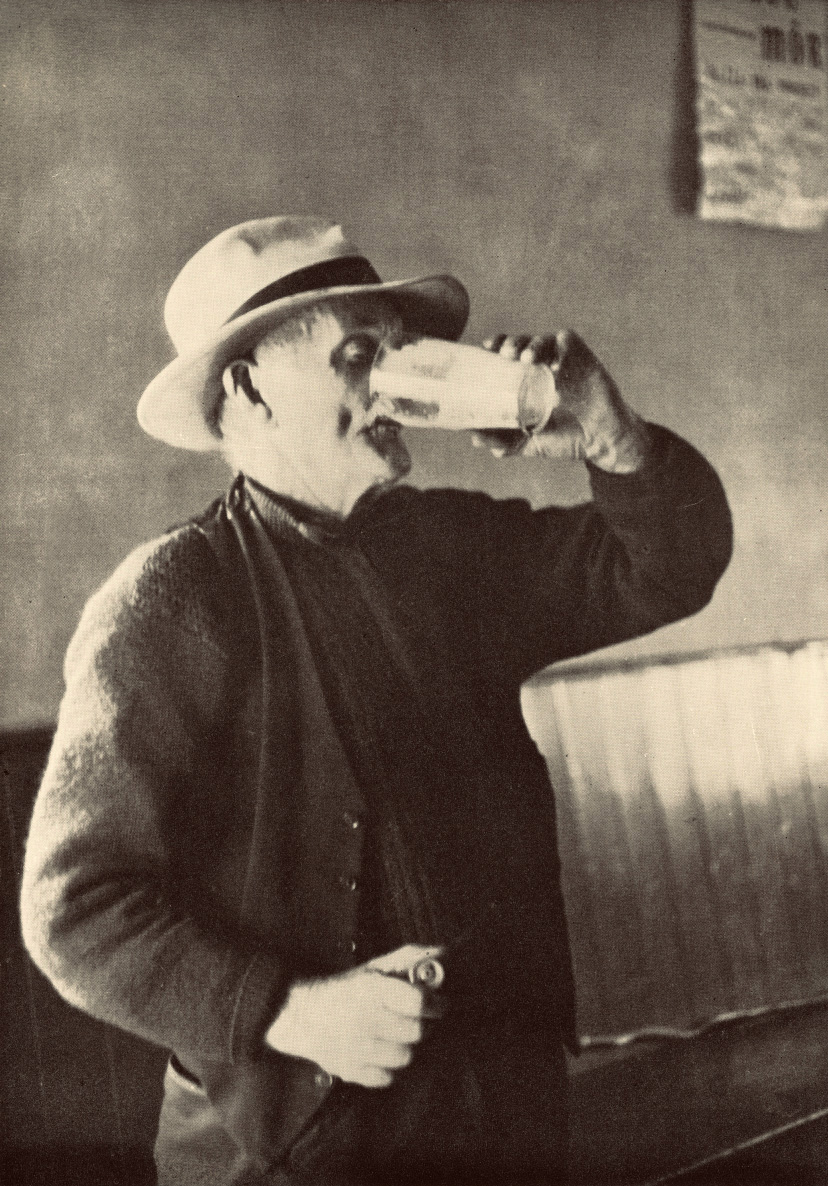

There is the photograph in the book, above. It is captioned Piontí Agus Píopaí – Pints and Pipes, hence the title of this post. Below it is a photograph of two Aran Island fishermen relaxing on the rocks while waiting for the weather to improve before they set out to sea. But there is more – a list of the photographs with some expanded captions at the end of the book. The whole book is written in Irish so I have recruited Finola’s help in providing a transcription for the Pints and Pipes – here it is, in the original and then translated:

Piontí Agus Píopaí

Ceathrar pinsinéirí ag baint spraoi as lá an phinsin le píopa agus le pionta Pórtair. B’fhéidir nach mbeadh pionta go hAoine arís acu. A saol ar fad tugtha ar an bhfarraige acu seo. Féach, cé gur istigh ón ngaoth agus ón aimsir atá an ceathrar go bhfuill an cobhar ar píopa gach duine acu. Is mar chosaint are an ngaoth a bhíodh an cobhar agus chun tobac a spáráil, ach ní bhainfí an cobhar anuas den phíopa instigh ná amuigh

Pints and Pipes

Four pensioners enjoying pension day with pipes and pints of porter. They might not have another pint until Friday. They’ve spent their whole lives on the sea. Look, even though the four of them are inside, away from the wind and the weather, the cover is still on each of their pipes. The covers are to protect the tobacco from the wind and to make it last longer and they aren’t taken off inside nor out

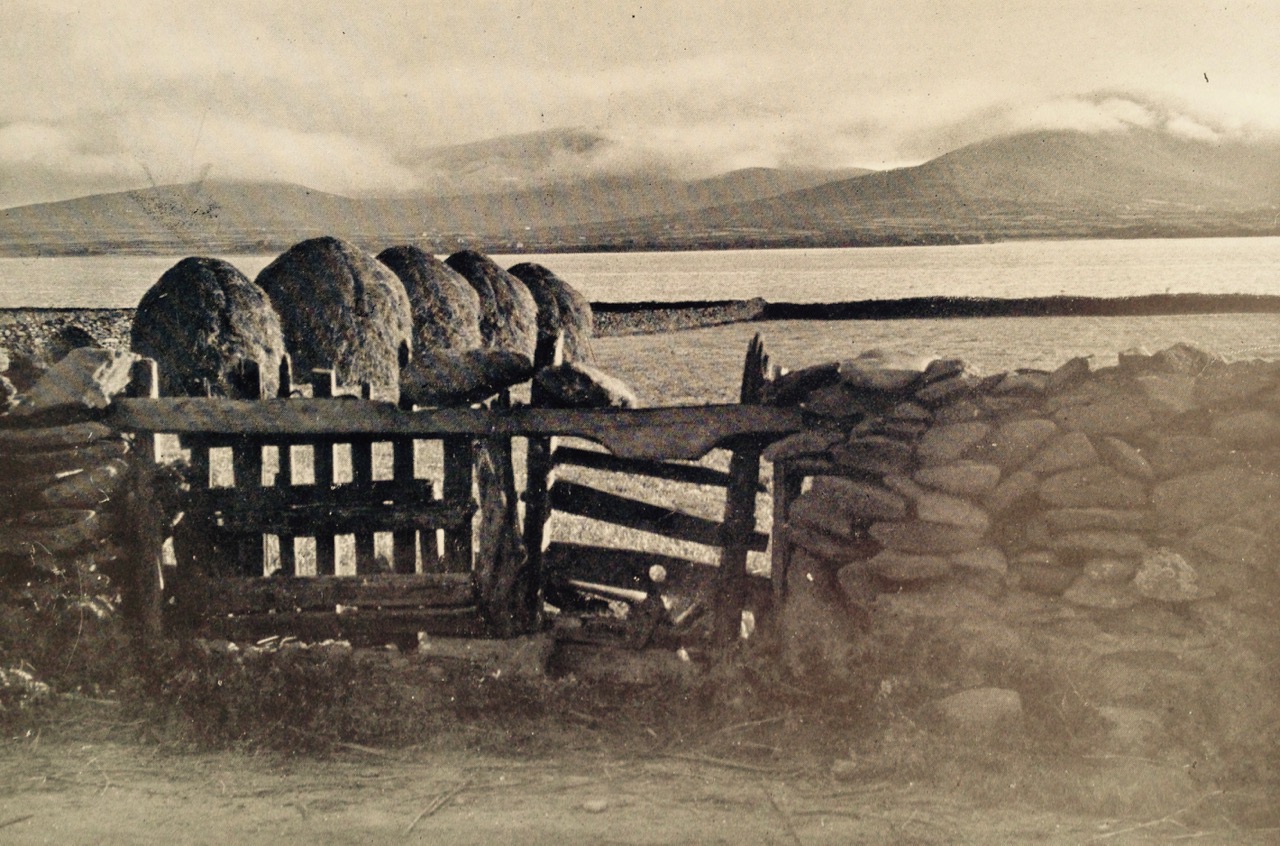

So, a fascinating piece of social history. Apart from conjecturing a date for the photo, I didn’t have much information to add when I first published it on Roaringwater Journal in February 2016. Because of the juxtaposition in the book, I guessed that the picture might have been taken around 1938, when Tómás is known to have visited and photographed the Aran Islands (and would have travelled through Kerry to get there). Here is one of his views of a Curragh being launched on Inis Meáin at this time (Dúchas):

I didn’t expect my story of Pints and Pipes to advance beyond this. But, last week, I received a message from a reader who had seen the photograph in Roaringwater Journal and was able to provide very significant additional information!

. . . My name is Joanne and I live in London. My dad found a photo on your website from a blog dated 14 Feb 2016 entitled Images – it is the Tomás Ó Muircheartaigh photograph of the 4 men drinking in a bar. My great-grandad is the man on the far left. It was great to find the photo as it is much better quality than the copy we have, unfortunately my nan had an original postcard but it was borrowed by a representative of Guinness many years ago and never returned!

Joanne, September 2021

Joanne has proved to be a wonderful contact, and I am so grateful to her for providing information and allowing me to use it here. In summary:

. . . My great-grandad’s name was Seán Mac Gearailt but he was known as Skip. He was from Baile Loisce in Kerry. The photo was taken in a bar which was then called Johnny Frank’s in Baile na nGall (Ballydavid) but I think is now called Tigh TP. I can see from the photos that have been digitalised Tomás Ó Muircheartaigh took a lot of photographs at Baile na nGall. Pints and Pipes isn’t in that digitalised collection . . .

. . . I gave my dad a call tonight and discussed the extract with him; he lived with his grandparents as a child in the late 1940’s/50’s and visited regularly so knows a lot about Skip. Dad remembers him collecting his pension on a Friday at Ballydavid and having a beer in Johnny Frank’s before going home to hand over the rest of the pension to his wife – so the extract in the book is correct on that. Skip was primarily a farmer but dad says he did go out fishing in a curragh at night. Dad remembers his nan being worried for him when he was out at sea. Dad doesn’t know the name of the other men in the photograph. Skip was friends with two Moriarty brothers (from Gallarus) – so dad thinks maybe the two men in the middle are them but he can’t know that for sure . . .

Joanne, September 2021

Wow! You can imagine how delighted I was to receive that information. But there’s more. I managed to find some early photos of Ballydavid (Baile na nGall in Irish), which is part of the Corca Dhuibhne Gaeltacht area. In fact we have been there – when we took the Irish language immersion course two years ago.

We didn’t photograph the Ballydavid bar, Johnny Frank’s at that time, but here (above) is a view of it from Wiki Commons. Also, to help set the scene, is a little piece online which features the bar, and weaves a tale…

Regular readers will know my interest in the Napoleonic-era signal towers which dot the coast of Ireland, all built in the early years of the 19th century. There was one at Ballydavid Head, drawn (above) by George Victor Du Noyer as he passed by on one of his geological expeditions on 12 June 1856. We didn’t climb the Head when we visited, but we viewed it from a distance (below). The tower is now a ruin.

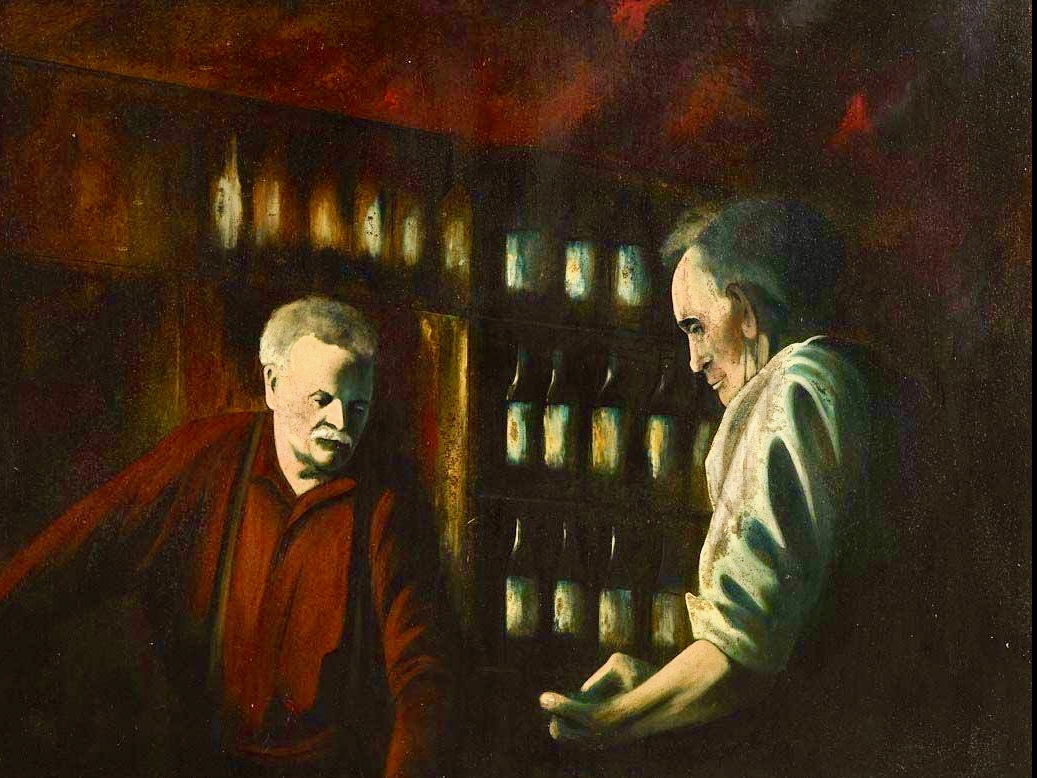

We have travelled far, far away from Ballydehob where, in some ways, the weaving of this tale began. We had better return. Here’s a reminder of that painted image of the ‘Pints and Pipes’ photograph in Levis’s Corner Bar. Compare it to the header photograph of this post.

It is so obviously based on the Tómás Ó Muicheartaigh portrait, yet there are some differences. The pipes of the two men in the middle are missing! I can’t tell you why this is the case, but I can tell you now who produced the painting, as I was given a valuable link by Joe O’Leary, landlord of Levis’s (which his been in his family for some generations – but that is another story). The painting has a signature:

Paul Klee was, of course, a well known Swiss-born German artist who lived between 1879 and 1940: he had no connection whatsoever with Ireland! Nor did he have anything to do with this painting, which was in fact from the brush of Raymond Klee, born in Barry, South Wales, in 1925 but living out much of his later life in Bantry, West Cork, until his death there in 2013. During the 1950s and 60s he lived in the Montmatre artists’ quarter in Paris, and is said to have been a close friend of Pablo Picasso. There can be no doubt that the Levis’s painting is his work, as I came across a short video, taken late in his life, in his Ballylickey Gallery. I managed to ‘freeze’ the fast-moving film at this point:

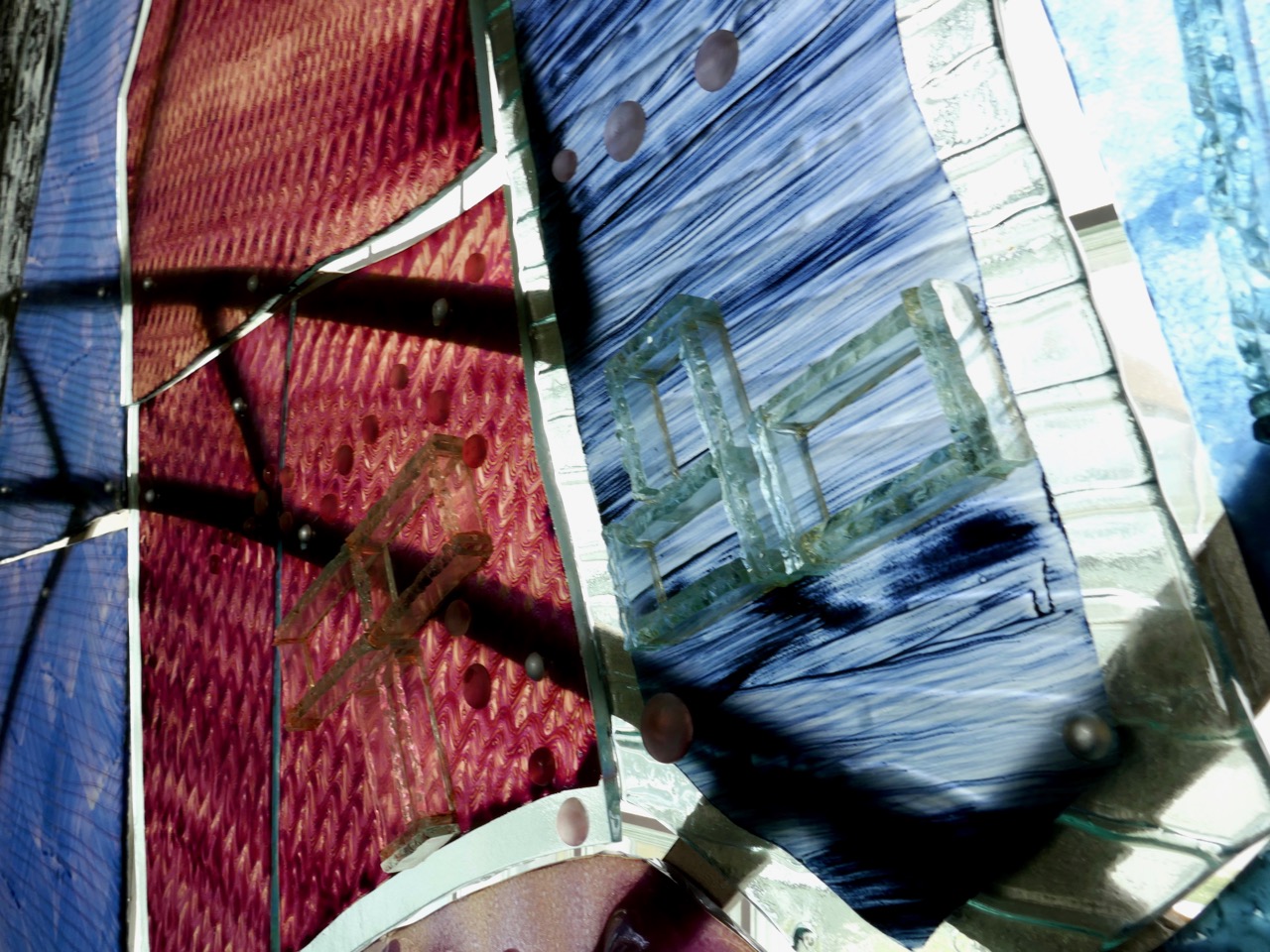

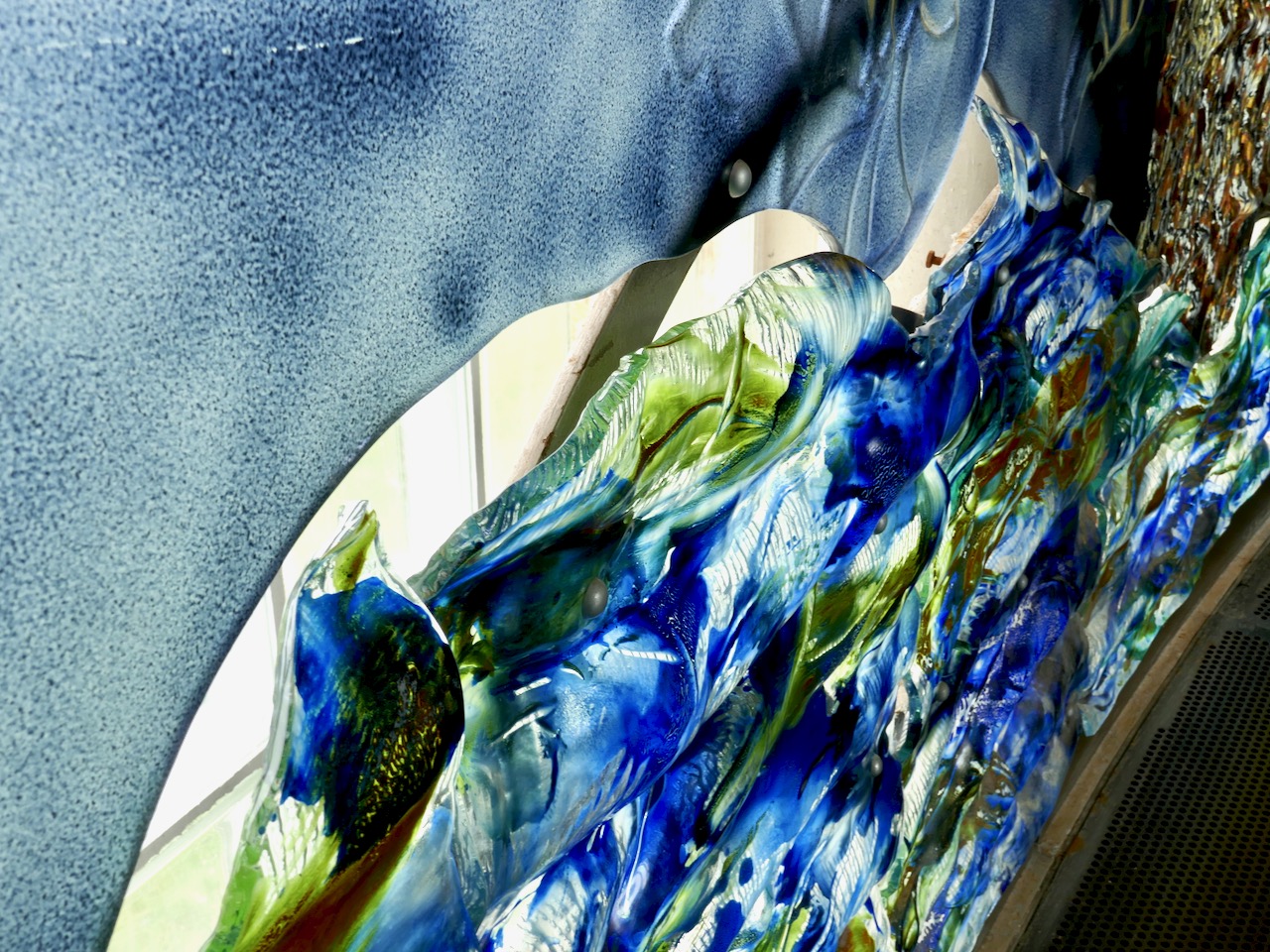

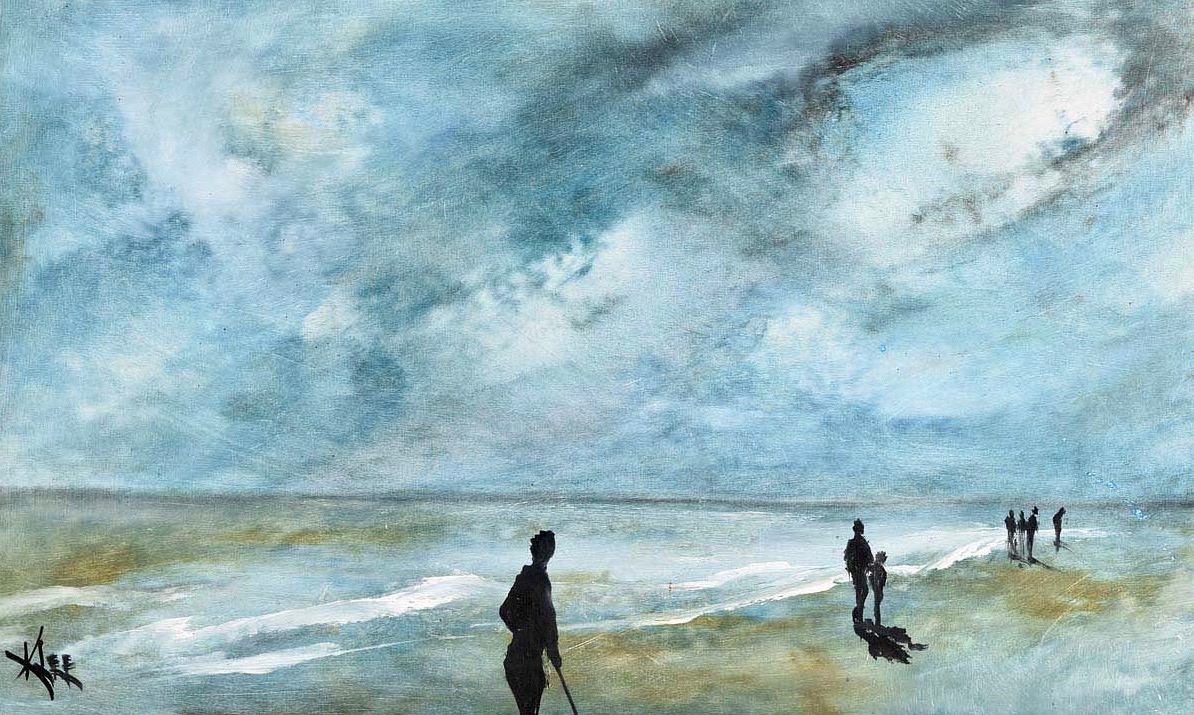

There, you can see the artist himself on the left, and over on the right is the partial image of a huge painting propped up: it’s another version of Pints and Pipes… I wonder what became of it? Or, indeed, of much of the large body of work which he left behind in Ballylickey? You will find examples on the internet, including several from the catalogues of art dealers. He doesn’t seem to have exhibited a particularly consistent style and – by repute – ‘churned out’ some of his works very quickly but – it has to be said – to a willing audience. During tours of the United States he would paint large canvases in front of a crowd – perhaps 200 spectators – and produce work which he immediately sold to the highest bidder in the room! I have selected a couple of images of paintings which might be of interest to my audience. The upper painting is titled The Local, while the lower one is Sky Over Inchydoney.

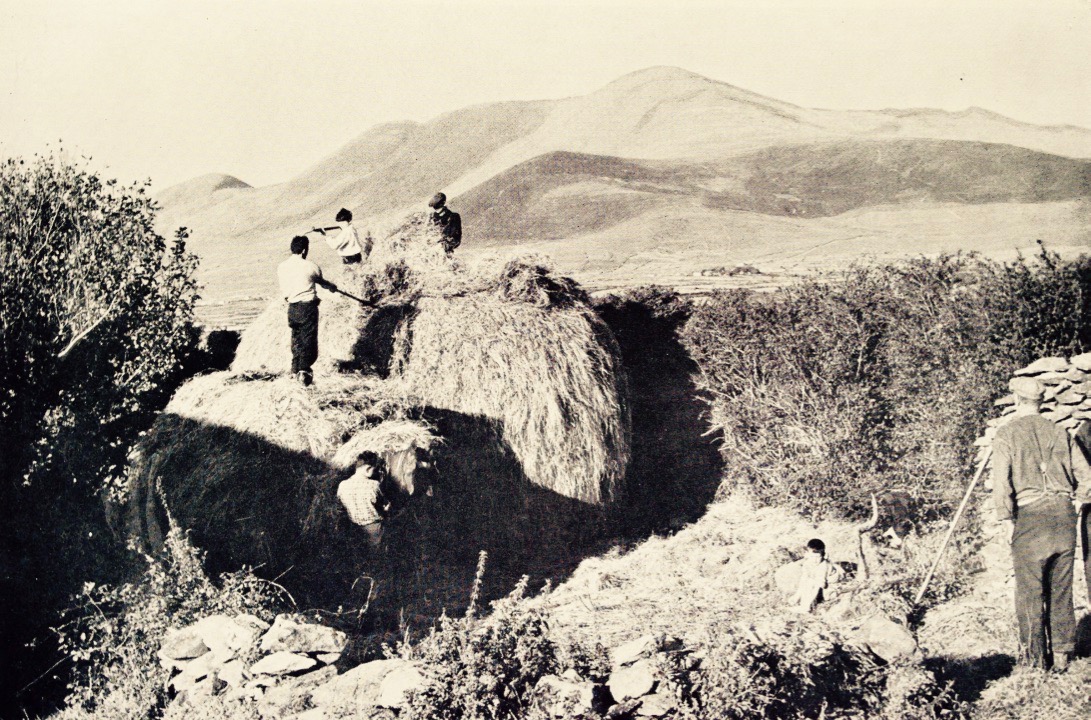

I must end my tale. Here is a little bonus, especially for my correspondent Joanne – and she won’t see this until she reads this post for the first time. We were leafing through the Tómás Ó Muicheartaigh book; it’s hard to put down – over 300 seminal photographs of Irish life. Finola’s eagle eye picked out one which I had never noticed before – and here it is: Seán Mac Gearailt, Joanne’s Great Grandfather, Skip. The caption underneath is apt. Many thanks, Joanne, for setting me on this journey…

GO mBEIRIMID BEO AR AN AM SEO ARÍS . . .

Thanks go to my very good friend Oliver Nares, who worked on the photographs of Pints and Pipes and Skip for me, and greatly improved their quality. Have look at his own site