Who was Asenath Nicholson? When I saw that a new play was to be performed during the Skibbereen Arts Festival this year, I became curious about the subject. The play, Welcome to the Stranger, is based on Asenath’s books, Ireland’s Welcome to the Stranger, and Annals of the Famine in Ireland written about her sojourn in Ireland before and during the Great Hunger. As an eye witness account of the conditions she saw, it is invaluable. So why is she not a household name?

As I discovered, there is actually quite a lot about Asenath available online, much of it centred on the research of Maureen O’Rourke Murphy of Hoffstra University, who has written the definitive book on Nicholson, Compassionate Stranger, as well as editing Asenath’s own writings for re-release. Prof Murphy has provided a piece about the book to Irish Central, and the book itself has been comprehensively reviewed in the Irish Times by Christine Kinealy, Director of Quinnipiac’s Great Hunger Museum. Both of these articles summarise Asenath’s life and the significance of her account of her time in ireland, so pop over there now for a quick read, and then come back here. There is also a lecture by Prof Murphy online (entertaining and erudite), as well as a very well-done radio documentary (although I can’t find out who produced it). These take a bit longer so save them for later.

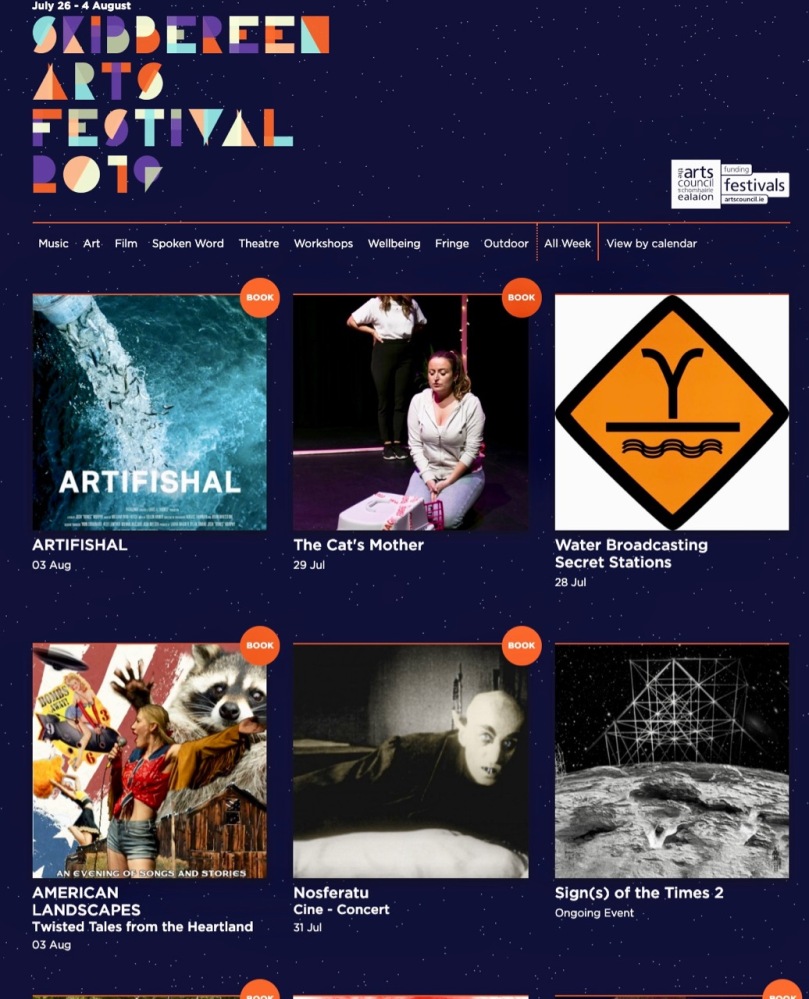

Rua Breathnach, the writer of the new play, is taking an interesting approach to depicting Asenath’s lengthy time in Ireland (four years in all) and the production is being staged and directed by his long-time collaborator, Rémi Beelprez. It will debut in Skibbereen on Aug 1, followed by a discussion session. Robert and I have our tickets already (you can get yours here) and are looking forward to seeing what Rua and Rémi have done with such rich source material.

Rua and Rémi

Seeking more information, I discovered that Ireland’s Welcome to the Stranger is available online in its original form, and also in a clickable version, and of course I was immediately drawn to the chapters about her time in West Cork and in Bantry in particular. This was in February 1845, before the potato crop had failed for the first time, but here Asenath describes perfectly the conditions that prevailed among the poor which led ultimately to the catastrophic events of the next few years – the extreme poverty and lack of resources, the lack of employment of any sort, and the dependence on a single food source.

Bantry as it is now, a thriving and attractive market town

Her chapter section heading is “Arrival at the miserable town of Bantry.” Here is why she went there:

When about leaving Cork for Killarney I intended taking the shortest and cheapest route ; but Father Mathew said, “If you wish to seek out the poor, go to Bantry; there you will see misery in all and in every form.” I took his advice, went to Bantry, and there found a wild, dirty sea-port, with cabins built upon the rocks and hills, having the most antiquated and forlorn appearance of any town I had seen; the people going about not with sackcloth upon their heads, for this they could not purchase, but in rags and tatters such as no country but Ireland could hang out.

This and the other wood engravings* are by James Mahony for the Illustrated London News of 1847, and are from Niamh O’Sullivan’s book, The Tombs of a Departed Race; Illustrations of Ireland’s Great Hunger, available at The Skibbereen Heritage Centre.

Asenath was in Ireland specifically to observe and record the conditions of the poor, but she was unprepared for what she saw in Bantry. She even feels moved to warn her readers, If you have tears, prepare to shed them now.

The morning opened my eyes to look out upon sights which, as I write, flit before me like haggard spectres. I dressed, went forth, and made my way upon the rocks, found upon the sides of them some deplorable cabins, where smoke was issuing from the doors, and looking into one, the sight was appalling – Like an African kraal, the door was so low as to admit only a child of ten or twelve, and at the entrance a woman put out her head, with a dirty cloth about it; a stout pig was taking its breakfast within, and a lesser one stood waiting at a distance. The woman crouched over the busy swine with her feet in the mud, and asked what I wanted?. . .Looking in, I saw a pile of dirty broken straw, which served for a bed for both family and pigs, not a chair, table, or pane of glass, and no spot to sit except upon the straw in one corner, without sitting in mud and manure.

There was a new workhouse in the town, which Asenath describes as lofty and well-finished but it was closed and shuttered, though all things had been ready for a year ; the farmers stood out, and would not pay the taxes. Asenath goes on to say The poorhouse was certainly the most respectable looking of any building in Bantry; and it is much to be regretted, that the money laid out to build and pay a keeper for sitting alone in the mansion, had not been expended in giving work to the starving poor, who might then have had no occasion for any house but a comfortable cottage.

The ruins of the Schull Workhouse

As an aside, in the end the workhouse did open, but the conditions in it were appalling. You’ll find a link to Dr Stephen’s report (be warned, it’s heart-rending) in our post about the Schull Workhouse, which also contains lots of information about workhouses in general.

Asenath refers to ‘wading’ through the streets of Bantry. She describes a set of dwellings called Wigwam Row: a row of cabins, built literally upon a rock, upon the sloping side of a hill, where not a vestige of grass can grow, the rock being a continued flat piece like slate. The favored ones who dwell there pay no rent, having been allowed in the season of the cholera to go up and build these miserable huts, as the air upon the hill was more healthy. And there, like moss, to the rocks have they clung, getting their job when and where they can, to give them their potatoes once in a day, which is the most any of them aspire to in the shortest winter days.

As she walks, Asenath sings hymns and dispenses tracts and testaments, some of which she keeps in an enormous bearskin muff. She attracts attention everywhere she goes and the children of Bantry follow her around. Begging is endemic and she is frequently cheated. However, she comes to admire the Irish and particularly their sense of hospitality and their generosity to her and to each other. In a typical description she writes about a Bantry woman with whom she interacts: I looked at this woman, and at the appurtenances that surrounded her. “The whole chart of Ireland,” from lips that could neither read English nor Irish! She had a noble forehead, an intelligent eye, and a good share of common sense; she had breathed the air of this wild mountainous coast all her sad pilgrimage, and scarcely, she said, had a “decent garment covered her, or a wholesome male of mate crossed her lips, save at Christmas, since the day she left her parents that raired her.”

Famine Memorial, Dublin

We will leave Asenath on the road to Glengarriff, struggling to make headway as the magnificent scenery claims her attention, to the relief of her helper, John, who, burdened with her ‘purse’ and her muff, is able to take frequent rests while she catches up. She has given us a unique, first-hand, eye-witness account of Bantry in 1844 – one that contrasts tragically with the beautiful market town we have come to know well. She went on to travel the length and breadth of the country and to open her own soup kitchen in Dublin at the height of the Famine, this time dispensing bread, rather than tracts – let’s follow up with her in August at the play!

The interior of an Irish cabin in 1844 by Francis William Topham, painting now in the Ulster Museum

This summer we also look forward very much (harrowing as it will be) to a major exhibition at Uillinn (the West Cork Arts Centre): Coming Home is an exhibition of the largest Famine-related art collection in the world. It’s on loan from Quinnipiac University in the US, and opens on July 20th. There will also be a very special Performance/Event at the Schull Workhouse by acclaimed Irish artist Alanna O’Kelly titled Anáil na Beatha, Breath of Life. Future posts!

*More about wood engravings, from Brian Lalor: The process is an exceptionally important pre-photography development in visual communication terms and, in its day (early 19C), quite as radical as email. The reporter, O’Mahony, drew on the spot in pencil, the drawings were sent by postal coach and packet boat to London where a team of engravers worked through the night to meet the publishing deadline, on the small (generally 4” square) blocks of fruitwood that fitted with the type into a letterpress printer. For speed, they often had a number of engravers working on a single image by using separate blocks which were then bolted together. On the ILS 1844 image of Ballydehob (not shown) you can see the joins.

Email link is under 'more' button.