This post might also have been called A Monument to Imprudence because of the story which it encompasses. But, first and foremost, it is a bit of an architectural wonder, and certainly worth the deviation from the motorway if you are travelling between Cork County and Dublin. It will add only 20 minutes to your journey – plus however long you decide to spend walking the publicly accessible woodland to discover the nineteenth-century extravagances of Arthur Kiely, Esq. Leaving the M8 motorway at Fermoy, head east towards Lismore on the R666: you will reach a car park and trailhead for Ballysaggartmore on the left within half an hour. After your visit, find the R668 heading north and rejoin the M8 at Cahir.

We felt we were capturing the last of the summer as we embarked on the beautiful sunlit trails on the first day of October in this Covid laden year. We were convinced that a week or so later we would be feeling the first cool winds of autumn and undoubtedly be noticing the changing hues in the ash, beech and oak tracts of the Ballysaggartmore Demense. The name in Irish – Baile na Sagart – means ‘Priests’ Town’. I cannot find out which priest is being remembered here, but – as you will see – there is some local lore which mentions a priest – and also Kiely, the unpopular local landlord.

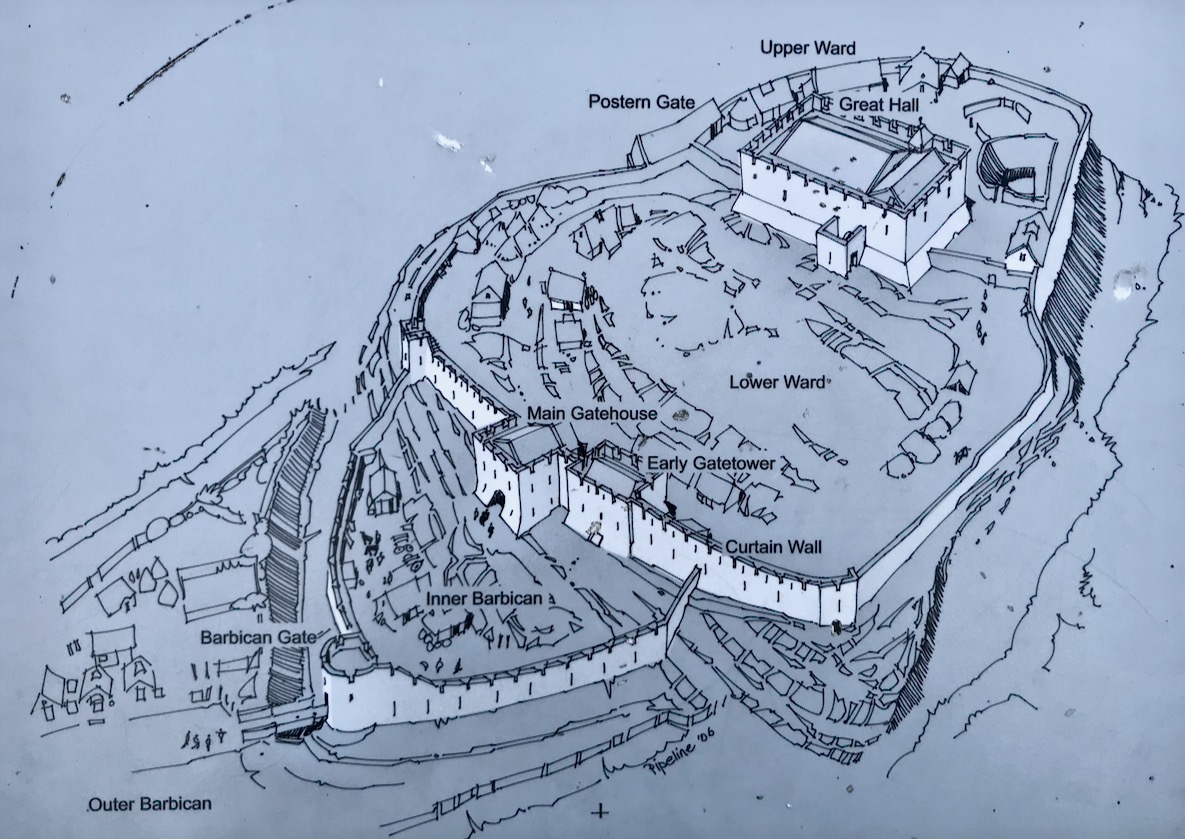

These extracts from the c1840 first edition 6″ Ordnance Survey maps show parts of the Ballysaggartmore Demense. In the upper plan, a house can be seen, probably newly built at the time of the survey. Nothing remains of it now, but some photographs exist, dating from 1904.

It’s time to piece together what can be found on the history of the place and its people. The first Kiely – John – purchased some 8,500 acres of land here in the late 1700s. He had two sons. On the senior John’s death in 1808 the elder brother – also John – inherited good lands at Strancally, on the Blackwater River, and proceeded to build an imposing castle there. The younger son – Arthur – had to make do with the less propitious lands around Ballysaggartmore, and built the modest house pictured above, but apparently harboured notions to match John Junior’s aspirations, embarking on a grand design to upgrade the property, starting with a splendid carriage drive and gatehouse which survives today near the beginning of our walk in the woods.

. . . Sir, Permit me through the medium of the Dublin Penny Journal an opportunity of giving the public a brief description of the situation and scenery of Ballysaggartmore, the much improved residence of Arthur Keiley, Esq, situate one mile west of Lismore, on the north side of the river Blackwater. The porter’s lodge at the entrance to the avenue is composed of cut mountain granite or free stone, of a whitish colour, variegated with a brownish strata, which gives the whole a rich and pleasing appearance; it consists of a double rectangular building, in the castellated style, flanked by a round tower at either end, through which is a passage and carriage-way of twelve feet in the centre, over which is a perpendicular pointed arch, enriched with crockets and terminated with a finial; the buildings at either side of the gateway, although similar, form a variety in themselves; and the situation is so disposed as not to be seen until very near the approach; the gate is composed of wrought and cast iron; and is, I will venture to assert, the most perfect gothic structure formed principally of wrought iron, in the kingdom. It was executed by a native mechanic, and cost about one hundred and fifty pounds . . .

Dublin Penny Journal, December 1834

The ambitions of Arthur Kiely knew no bounds. Egged on by his wife, jealous of her in-law’s estate at Strancally, he continued the carriage drive (today a further part of the picturesque walking trail) towards a humble stream which had to be crossed in order to reach the vicinity of the house which was to be upgraded to – or replaced by – something of suitable substance. The stream could easily have been culverted but no! Only an ornate neo-Gothic three-arched bridge with gate-houses at either end and surmounted by towers and pinnacles would do: a prelude, presumably, to the architectural magnificence that was being planned beyond.

At the same time as directing the building project, Arthur decided that a change of name would be advantageous. Something double-barrelled was called for, and he chose to add Ussher, a family name derived from ancestors on his mother’s side. Arthur Kiely-Ussher certainly has a ring to it. Arthur’s ambitious wife was born Elizabeth Martin of Ross House, Co Galway. Always on the look-out for a West Cork connection, I can tell you that the author Violet Martin was a great-niece of Elizabeth. Violet lived in Castletownshend and famously collaborated with Edith Somerville.

The gate-lodge and ‘Towers’ of Ballysaggartmore are remarkable survivors, and represent the sum total of Arthur’s striving to equal his brother’s show of opulence. After the extraordinary towered bridge the carriage drive peters out, and one assumes the money also dissipated. Kiely-Ussher attempted to revive the fortunes of his estate but this centred on evicting tenants in time of scarcity, which only resulted in the lands becoming less productive. The family lived through the famine but were considered notoriously bad landlords. In the 1850s Ballysaggartmore Demense was virtually bankrupt: the house was sold in 1861 and Arthur himself died shortly afterwards.

Like many another bad landlord, Arthur Kiely-Ussher has entered into folklore. It’s worth reading this lengthy entry from the Duchas Schools Folklore Collection – a superb tale of just retribution being visited on the memory of – not one – but three ghastly incarnations of a man who probably wished to be well remembered, but failed catastrophically.

. , . In Ballysagart there lived three landlords named Ussher Kiely. The three of them were brothers and they were all called Ussher. They were terrible tyrants and they evicted people every time they got the chance, and allowed no one near their land. Of the many stories told about their cruelty here is one: On Ussher’s land there is a Spring well. A very old, goodliving woman lived near the place. One day she had no water. The nearest place she could get water was the well, which was in a field behind her house, but Ussher allowed no one near the land. The neighbours always brought her a churn of water from the Blackwater, but this day she had no one to get it for her. As the Blackwater (which was two miles away) was too far for her to walk, she thought there would be no harm in going to the well for once. When she was bending down to fill her gallon in the well she heard a shout behind her; “Get away from that well and get off my land you cursed wretch. How dare a dying old hag like you interfere with my water or dirty my land with those rotten feet of yours”. It was the eldest Ussher and he made her throw back the water and he threatened to beat her if she did not get off his land immediately. She obeyed and when she was out of his sight she knelt down and cursed him saying “O God, may the brothers of this man, Ussher, who hunted me away without a drop of water, be at his funeral before the year is out, and may he grow silly and his tongue hang out of his head so that he cannot offend you again”. Another woman cursed him saying “May you die in agony, you tyrant”. Before the year was out he grew silly, and he had to be sent to a home where he died in terrible agony. His body is still to be seen in Ballysaggart where his body is embalmed in glass. His mouth is to be seen wide open and his tongue is hanging out and is as black as soot. Another of the Ussher Kielys saw a man crossing his land. He brought out his gun and threatened to blow the man’s legs from under him. The man who was only going home said “Ussher Kiely, I was walking on this land before you and I’ll be walking on it after you, so why don’t you shoot me”. Ussher put away the gun and never used it again. A few days later he complained of pains and only lived two hours. He was embalmed in glass and laid by his elder brothers side. The third Ussher Kiely was worse than the others. Every night a man used to bring cattle on Ussher’s land to graze. Ussher heard of this and one night he lay in wait and without warning shot the man. When the people heard of the shooting they piled curses on Ussher. A few days passed since the shooting when a priest was walking on Usshers land. He was reading his ‘Office’ when he met Ussher. Ussher cursed him and called him every name he could think of as well as ordering him off the land. “All right”, said the priest, “I’ll go off the land, but mark my words, tyrants like you never live a long life”. Two hours later the last of the Kielys dropped dead. The three brothers are to be seen, embalmed in glass lying side by side in a small graveyard in Ballysagart . . . Mr Tom O’Donnel told me these stories – Tom Conway

Duchas Schools Folklore Collection, Volume 0637

If you would like to read in greater detail the fortunes and fall of Arthur Kiely-Ussher I commend you to the excellent account by The Irish Aesthete. The ‘modest’ house at Ballysaggartmore was burned down during the Irish Civil War, obliterating its physical history and committing its memories to fascinating folk recollection. We are fortunate, nevertheless, that we may freely wander a trail and reminisce on misfortune. And justice.