This was the scene in the Working Artist Studios, Ballydehob, on Friday evening. It was the launch of a brand new book by our friend Amanda Clarke: Holy Wells of County Cork. That’s Amanda, above, in the centre, with Finola on her left. Regular readers will know that we share many adventures with Amanda and Peter, and we were so pleased to see the successful fruition of her years of research with this outstanding volume, exquisitely designed by Peter, now available to purchase online, and in bookshops. Finola wrote about this venture last week. I thought I would indirectly celebrate it today by reviving a Roaringwater Journal post from five years ago, about one of our own expeditions that included a visit to a holy well.

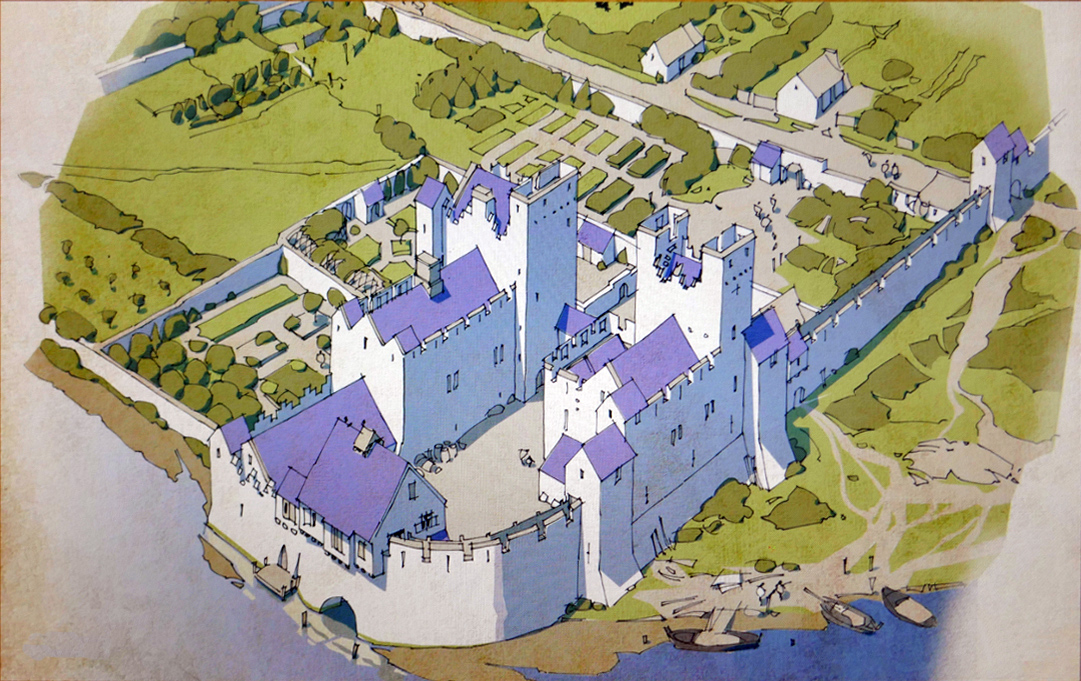

Once again we followed in the footsteps of Amanda and Peter: they had visited the Glen of Aherlow in County Tipperary and pointed us to St Berrehert’s extraordinary site at Ardane which I described in this post. Not far away is another site, equally remarkable, and related to St Berrehert’s Kyle in that they were both restored by the Office of Public Works in the 1940s. They are also both very easily accessible in a few minutes from the M8 motorway at Cahir.

We were delighted to be travelling again through the beautiful Glen in the shadow of the Galtee Mountains (above) as we searched out a boreen that led us down to the railway. We parked and crossed at the gate, watching out carefully as this is the Waterford to Limerick Junction line used by two trains a day (except on Sundays!)

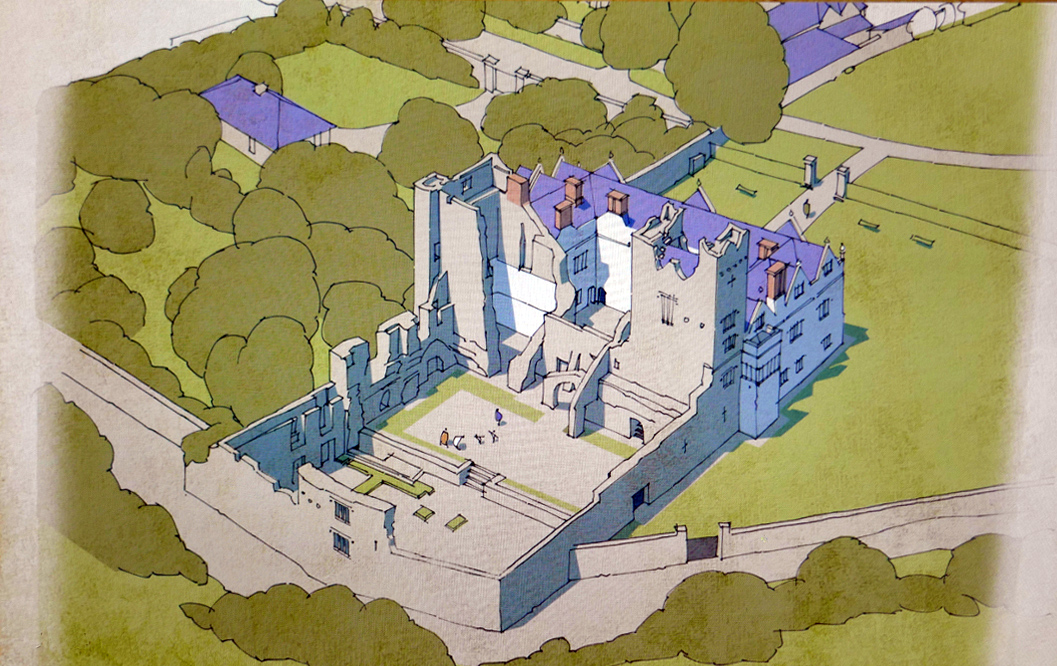

Once across, we were in an idyll. It’s a private lane, running alongside a gentle stream, but the Bourke family allow visitors to walk (as they have done for centuries) to the old church, the cell and the holy well of Saint Péacáin. Ancient stone walls line the way, and trees overhang, shading the dappled sunlight in this most exceptional of Irish seasons. We met Bill Bourke, who regaled us with tales of his life spent mostly far away from this, his birthplace – but who returned to rebuild the family home and to enjoy perpetual summer in what is, for him, the most beautiful setting in the world. He also told us of the crowds who used to come to celebrate St Péacáin at Lughnasa – 1st August – paying the rounds and saying the masses.

In her monumental work (it runs to over 700 pages) The Festival of Lughnasa – Oxford University Press 1962 – Máire MacNeill points out the harvest feast day was such an important ancient celebration that it survives as the focus of veneration of many local saints who would otherwise have been known for their own patron day, and she particularly mentions Tobar Phéacáin in this regard: a place well away from any large settlement where the great agricultural festival was so critical to the cycle of rural life.

The rural setting of St Péacáin’s Cell can be seen above, just in front of the trees; the church and the well are nearby. MacNeill provides a description of Tobar Phéacáin and includes some variant names:

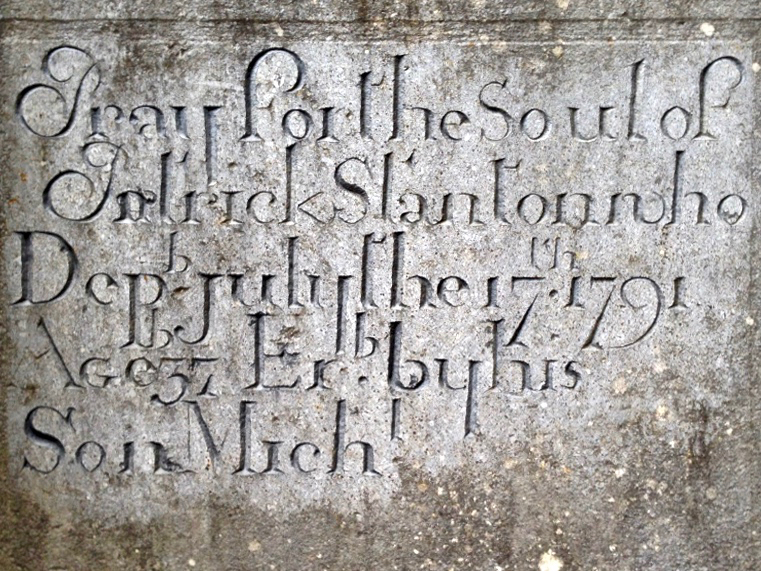

. . . Tobar Phéacáin (Peakaun’s Well), Glen of Aherlow, Barony of Clanwilliam, Parish of Killardry, Townland of Toureen . . . On the northern slope of the Galtee Mountain at the entrance to the Glen of Aherlow and about three or four miles north-west of Caher there is a well and ruin of a small church. About a mile beyond Kilmoyler Cross Roads a path leads up to it . . . In 1840 O’Keefe, of the Ordnance Survey team, reported that the old church was called by the people Teampuillin Phéacáin, or just Péacán . . .

. . . The well, which he described as lying a few perches south-east of the church was called Peacan’s Well or Tobar Phéacáin. It was surrounded by a circular ring of stonework. He stated: ‘The pattern-day still observed at this place falls on the 1st of August, which day is, or at least until a few years since, has been kept as a strict holiday.’ Devotions were also, he said, performed there on Good Friday . . .

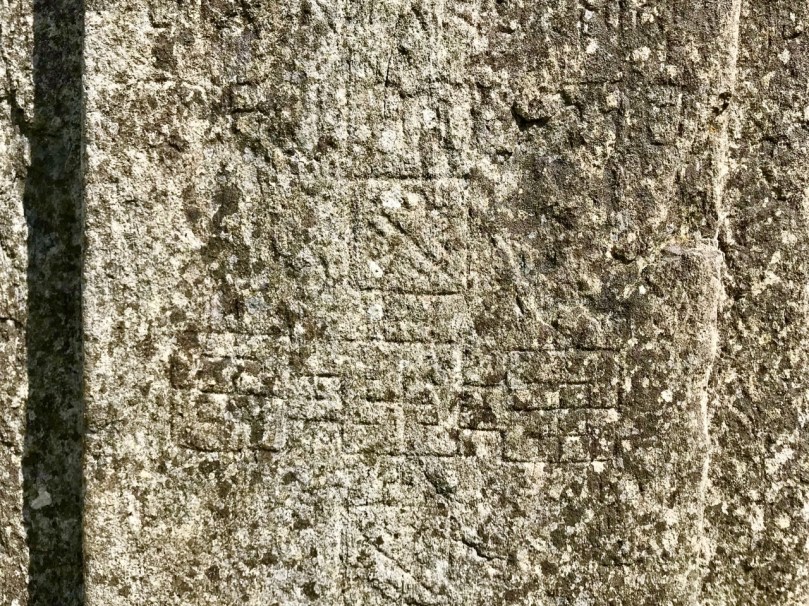

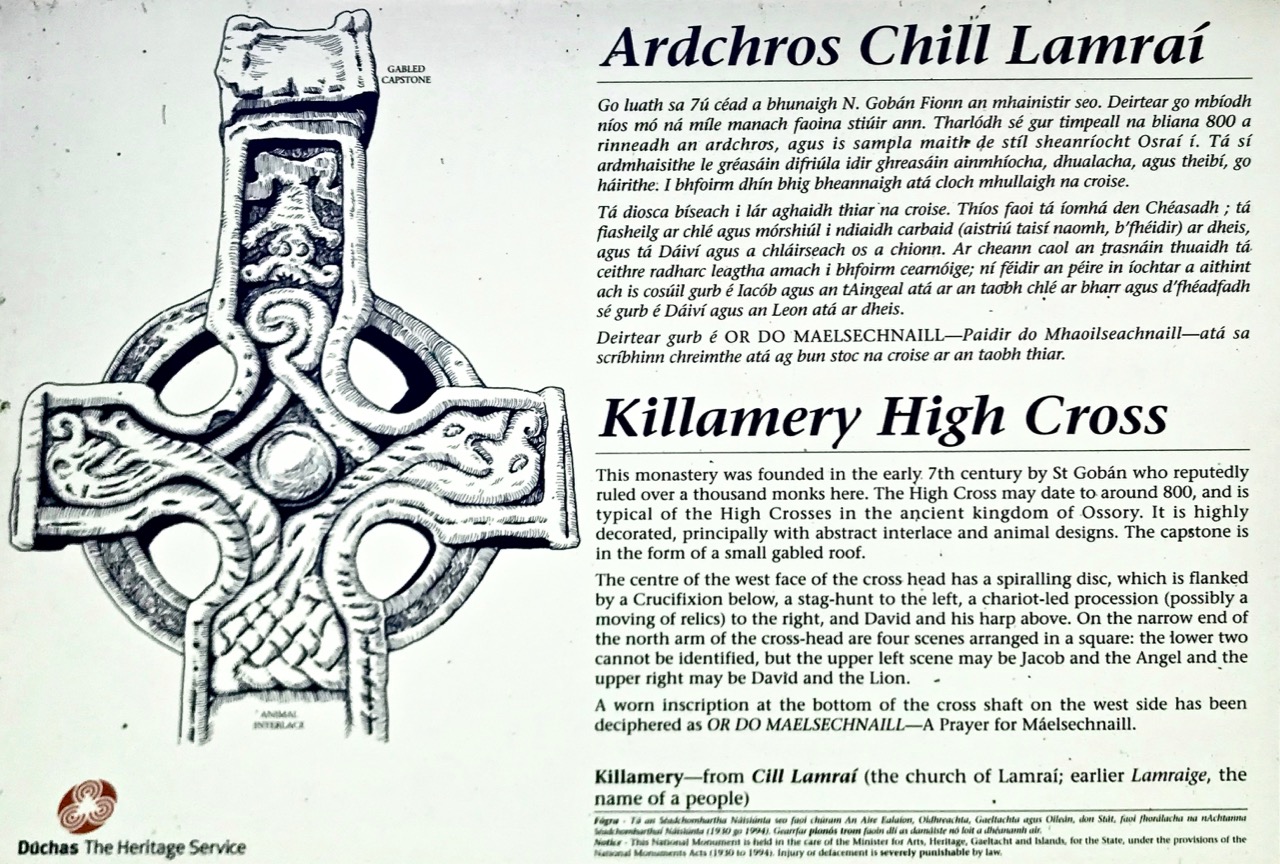

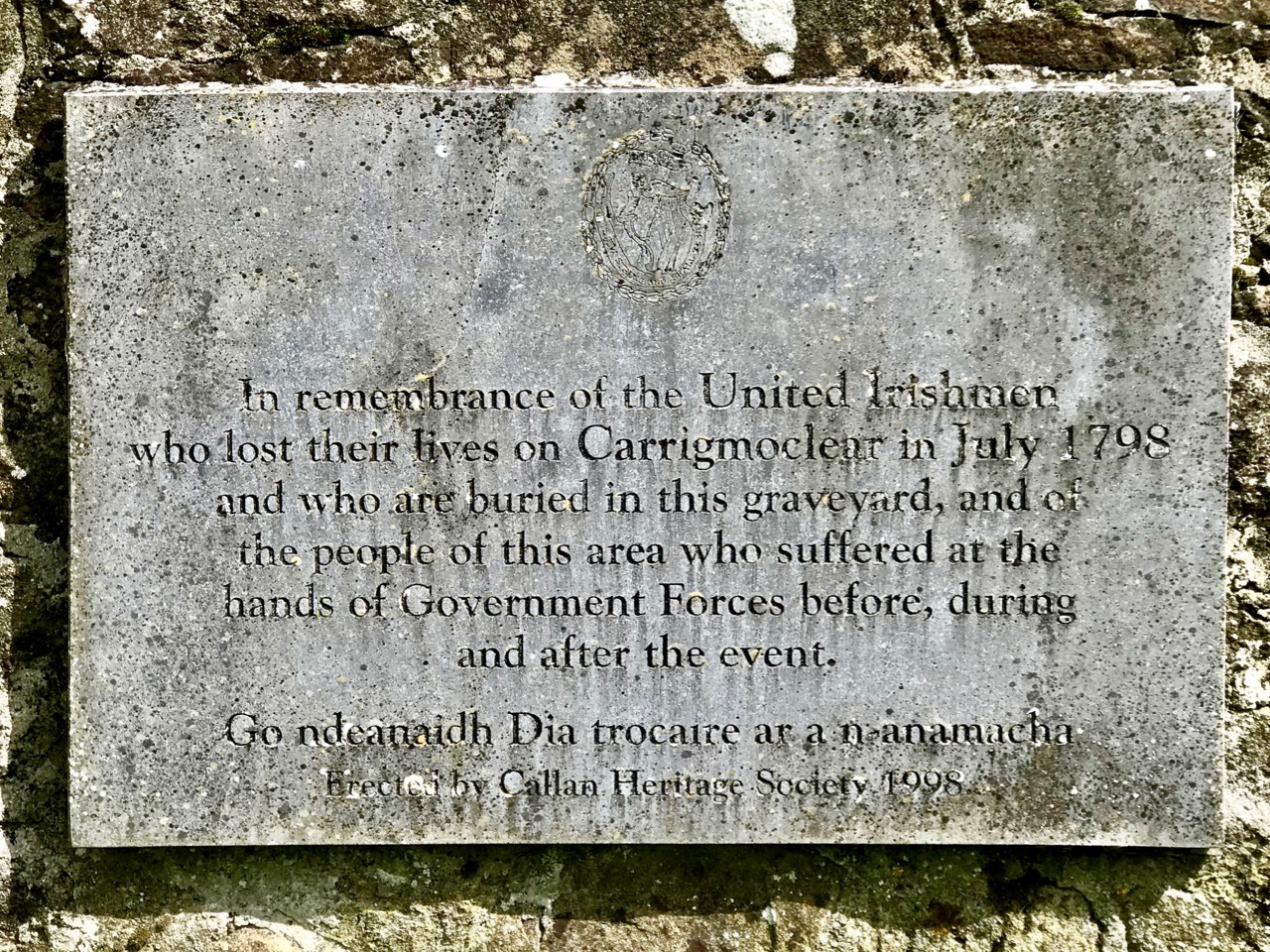

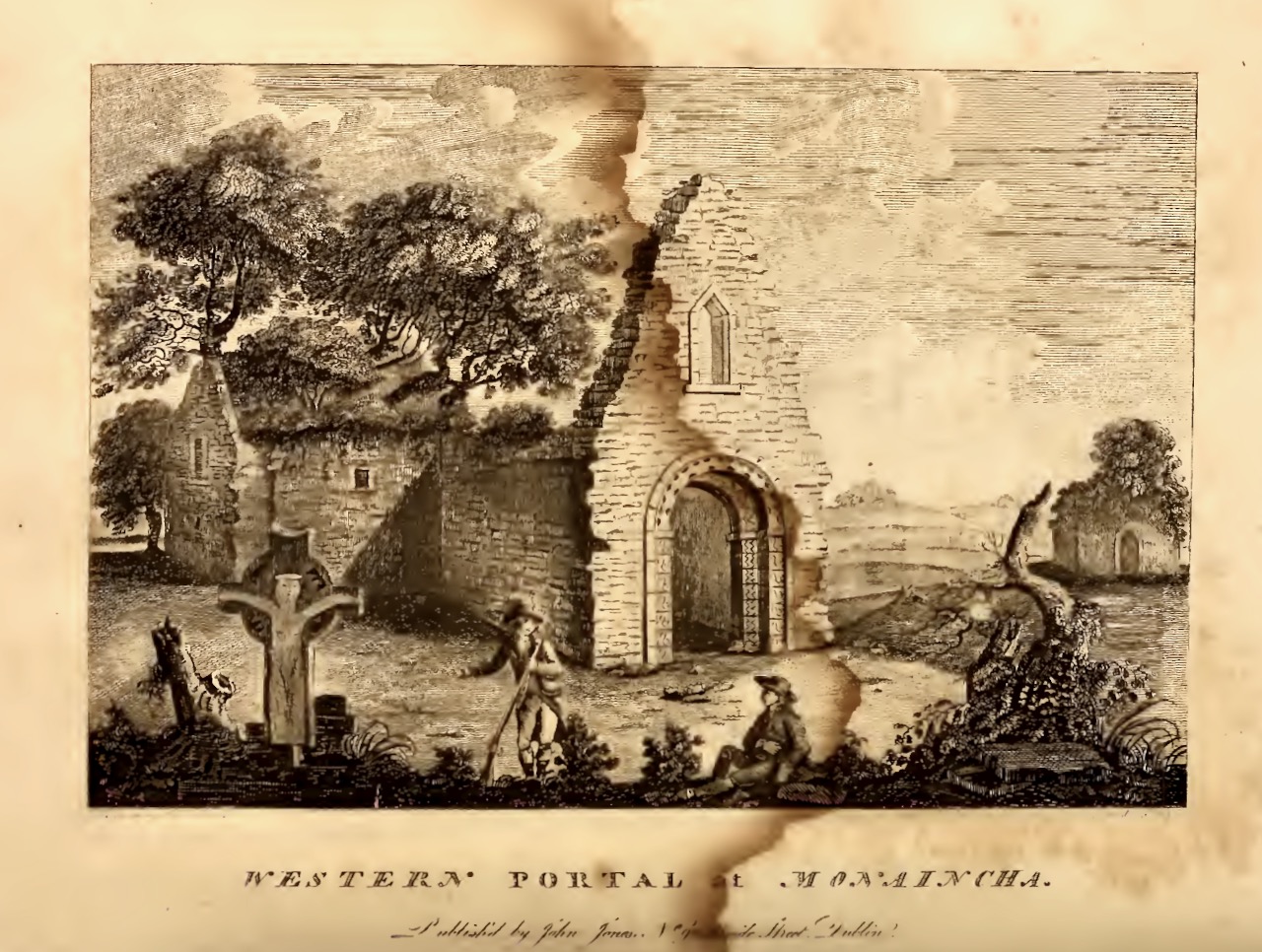

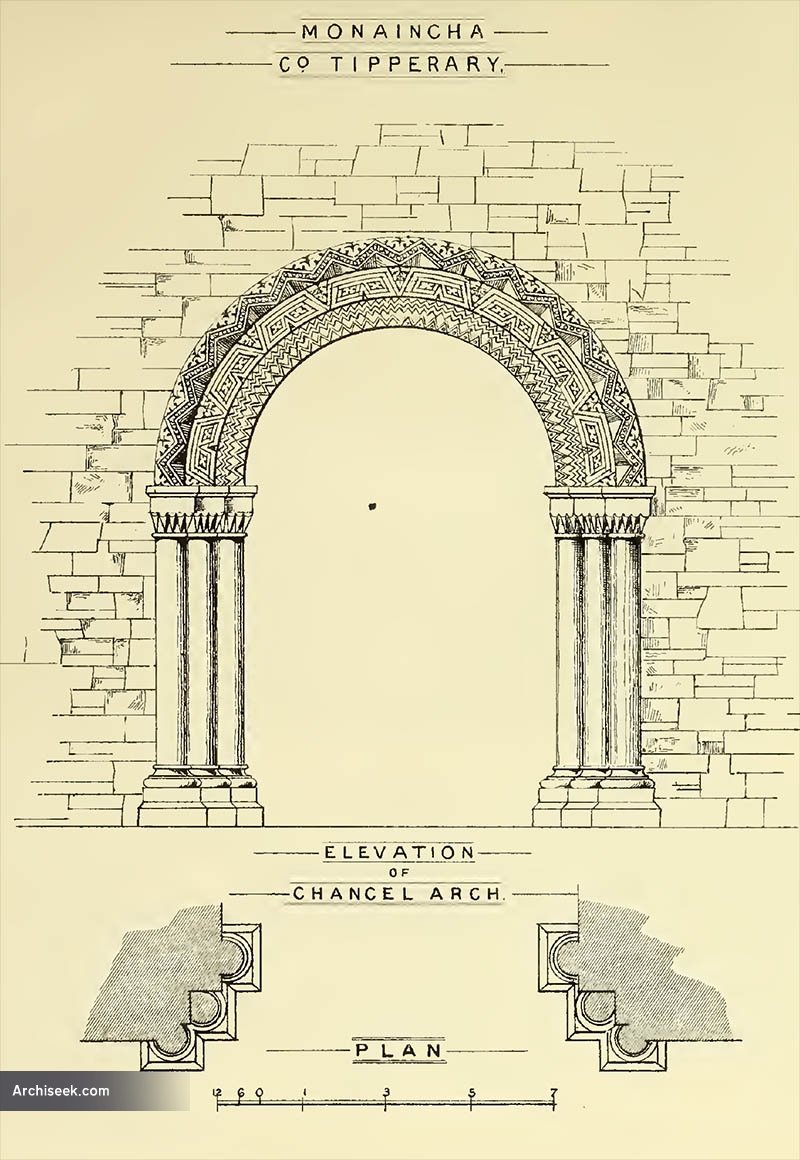

A hundred years after O’Keefe wrote this, the church ruins were tidied up by the Office of Public Works. As at St Berrehert’s Kyle, it seems there were numerous carved slabs on the site and remnants of high crosses, implying a significant ecclesiastical presence here. All these have been fixed in and around the church ruin for safekeeping, and in an intelligent grouping. It’s wonderful to be able to see such treasures in the place they were (presumably) made for, and to experience them in such a remote and peaceful ambience.

McNeill continues:

. . . Nearby is the shaft of a cross which tradition avers was broken in malice by a mason who was then stricken with an inward pain and died suddenly as a punishment for his sacrilege . . . O’Keefe was told a story of a small stone, 6 or 7 inches long and 4 or 5 in depth, having ten little hollows in it and resting in a hollow of the ‘altar’ of the old church. Christ, or according to others St Péacán, asked a woman, who had been churning, for some butter; she denied having any and when the visitor departed she found the butter had turned into stone which retained the impression of her fingers . . . Nuttall-Smith speaks also of a cave where the saint used to practice austerities . . .

The carved fragments are quite remarkable and are in all likelihood well over a thousand years old. I have yet to see anywhere in Ireland – outside of museums – which has such an extensive collection of fascinating medieval antiquities as these sites in the Glen of Aherlow. Here you can also see cross slabs and a sundial said to date from the eighth century.

Nuttall-Smith’s ‘cave’ – quoted by MacNeill above – is likely to be St Péacáin’s Cell, set in a field on the far side of the river. This was probably a clochán, or beehive-hut, of the type once used by anchorites. It is protected by a whitethorn tree, but was quite heavily overgrown on the day of our visit. We could make out the ballaun stones inside, said to be the knee prints of the Saint who made his constant devotions there. Amanda – in her post on the holy well – reports that Péacáin would also stand daily with arms outstretched against a stone cross, chanting the psalter.

McNeill discusses the significance of weather at the August celebrations:

. . . Paradoxically for a day of outing so fondly remembered, no tradition of the Lughnasa festival is stronger than that which says that it is nearly always rainy. No doubt this has been only too often experienced. Saint Patrick’s words to the Dési: ‘Bid frossaig far ndála co bráth’ (Your meetings shall always be showery) must be as well proved a prophecy as was ever made. Still there must be more significance in the weather beliefs than dampened observation. Certainly it was expected that rain should fall on that day, and sayings vary as to whether that was a good or bad sign . . . There are a few interesting beliefs about thunder, which was also expected on that day: the loud noise heard at Tristia when the woman made rounds there to have her jealous husband’s affection restored; the prophecy that no-one would be injured by lightning at Doonfeeny, a promise also made by St Péacán . . .

The holy well is tucked away in a stone-walled enclosure hidden under the trees on the edge of the field which contains the Saint’s cell. It is also a tranquil place, obviously still much visited: the water is crystal clear, refreshing and will ensure protection from burns and drowning. This is a magical setting to complete our day’s travels in the beautiful Glen of Aherlow.