John Speed was one of the greatest of Britain’s map-makers, but it is unclear how much actual original cartography he did. Much of the information in his maps appears to be based on Mercator’s maps, which we featured in Mapping West Cork, Part 1. What does appear to be original, as there are no previous records of them, are the city maps, so we can be reasonably sure that these were done from his own calculations – laid out by paces rather than by measuring implements.

Who was John Speed? Born in 1551, he trained as a tailor but his passion was for maps and he finally worked his way into a full time position as a historian and geographer, even being allocated a room for his research by Queen Elizabeth I.

His magnum opus was The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine, published in 1611 and 12. This marks them as later than Mercator’s maps, but earlier than Joan Blaeu’s (see Part 1). They were also drawn with the collaboration of Iodicus Hondius, who had drawn Mercator’s, which also explains the similarities to Mercator’s maps.

The edition of Speed’s atlas that is most often referenced is the one published in 1676, and that is the one that the wonderful David Rumsey acquired and uploaded to his map collection site. Until I read the fine print, I hadn’t realised that the maps in fact dated to 1611/12 and therefore were older than the Blaeu atlas.

This is the period immediately following the Battle of Kinsale in 1603, which marked the decisive end to the Nine Year’s War, and to the old Gaelic way of life. The maps were also made in the period after the failed Desmond Rebellions of 1569–1573 and 1579–1583. They still name the great Irish families rather than the English planters who would so totally supplant them over the course of the next century. In this regard, it is an important record of what was happening on the ground in 1611.

Along with his Atlas he produced a work that combined history and geography – the Invasions of England and Ireland, in 1601 and 1627. He was, of course, a devoted subject of the Queen (‘her sacred maiestie’) and his political opinions tended to the conservative, if not puritantinical.

This map is accompanied by the history of invasions, with suitable illustrations. I am particularly taken with the depiction of ‘Desmond beheded’

True to his day, he depicted the Irish quite differently from the British – the lowest grade of English person was the Countryman or Country woman, whereas in Ireland it was the Wilde Man or Woman.

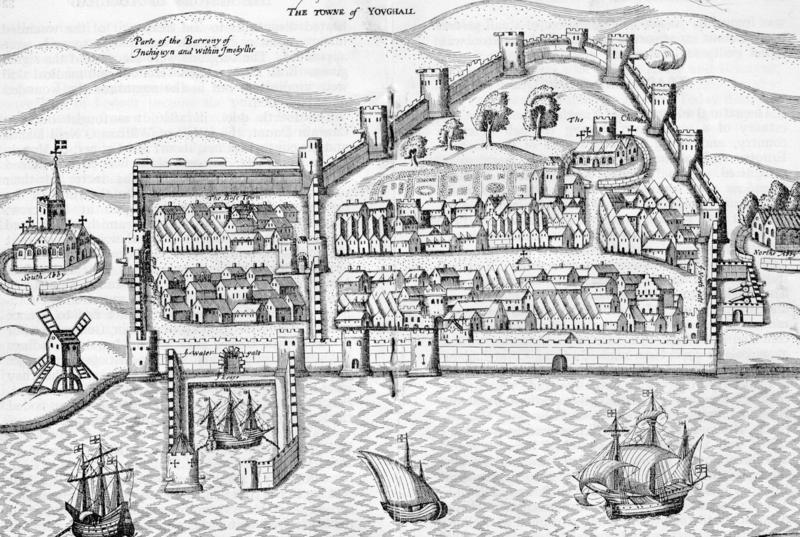

The city maps were all new and it seems that Speed, with one of his sons, actually travelled to the cities he includes in his atlas and paced out the distances, drawing the maps based on these calculations. They are a unique and invaluable record of a time when Ireland had walled cities, especially given that so few intact stretches of those walls remain. (We’ve visited some impressive remains, though – see Youghal’s Walls and our post on the walled town of Fethard.)

The Dublin map is from a later edition

The actual physical depiction of the land is recognisably based on the Mercator map but there is more information now about locations and families. I was delighted to see Rossbrin show up (Roßbrenon) along with Ardintenant (Artenay), since it is this castle that we look across to from our home. Mizen Head and Brow Head are both marked, and the Sheep’s Head is also noted as Moentervary (Muintir Bheara is the Irish designation for that Peninsula).

Besides the O’Mahonys, the O’Driscolls, the McCarthys, the O’Donovans, Sir Peter Carew occupies a chunk of land. Someday I will write about his claim to that land and the lengths he went to to secure the deeds to it. But perhaps I shouldn’t be too exclusive to West Cork: below is a section of North Cork and part of Kerry in 1612. What can you see?

Maps drawn by a colonising power, have an agenda far beyond simply charting the territory. John Speed’s became the defining maps of the expanding British Empire during the seventeenth century and indeed they influenced British people’s perceptions of the world until well into the eighteenth. For us in Ireland, and in West Cork, they are an invaluable social document.