It’s surprising that it’s taken us eight episodes of this series to reach Brow Head, as it is one of the nearest to us, and one of the best preserved – albeit a ruin. It’s not far from the last one we explored: Cloghane, on Mizen Head. In fact, at 3.8km apart, these two towers are the closest of any in the whole system of signal towers around much of the coast of Ireland: 81 towers, each one generally in sight of two others.

Above – views north-west across to Cloghane, Mizen Head, from Brow Head. The lower photo is taken with a long lens. Cloghane is 3.8km away from Brow Head: it doesn’t sound very far but, as you can see from the centre picture here, it’s remarkable that telescopes were good enough, in the early 19th century, to make out visual signals in any great detail. Weather conditions were obviously an important factor in this. Below, the tower at Knock, Lowertown, near Schull, is some 19km away to the east. When we visited the vestigial Ballyroon signal tower, on the Sheep’s Head to the north, we could also clearly see across to Brow Head – a distance of about 17km.

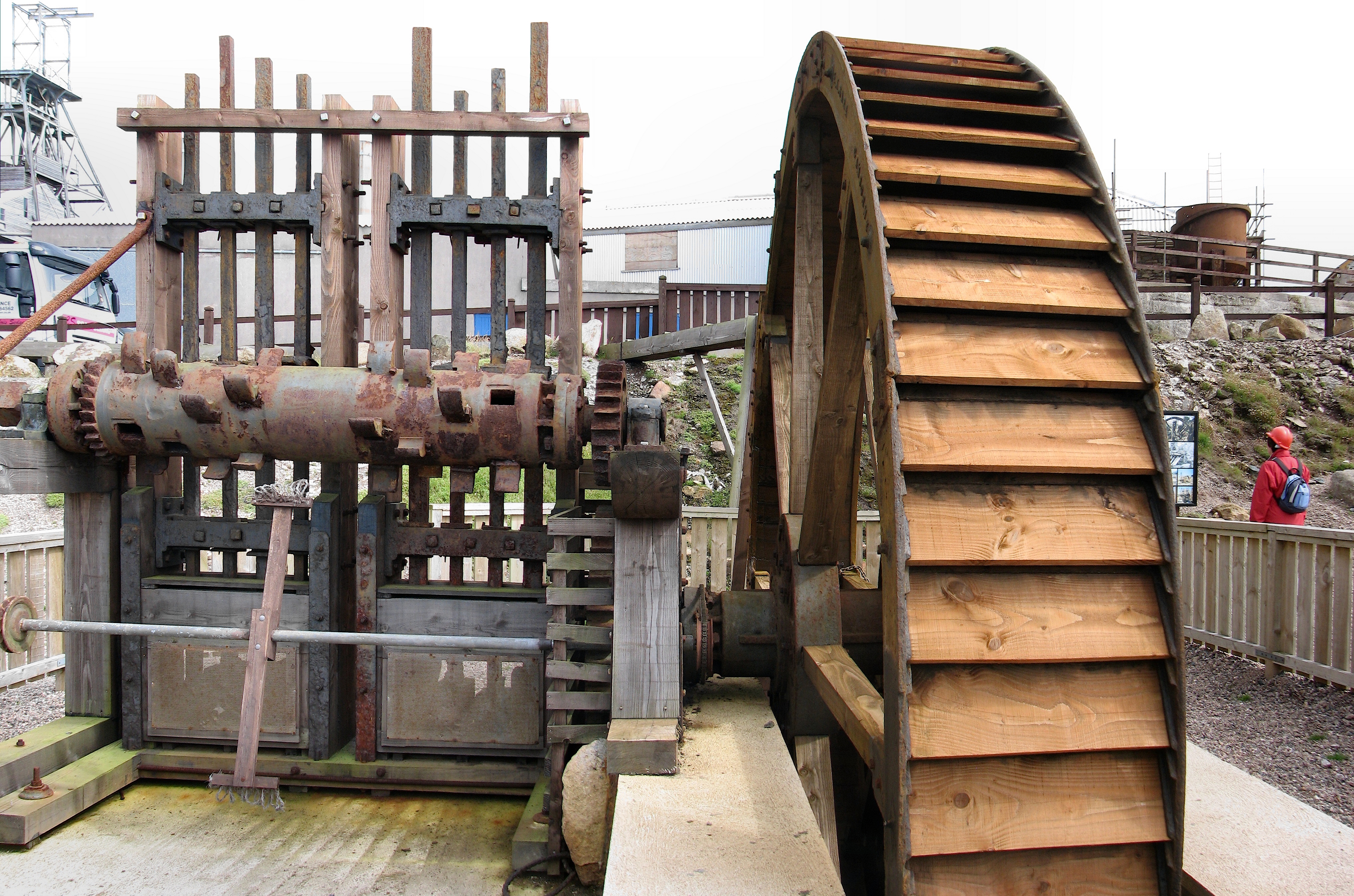

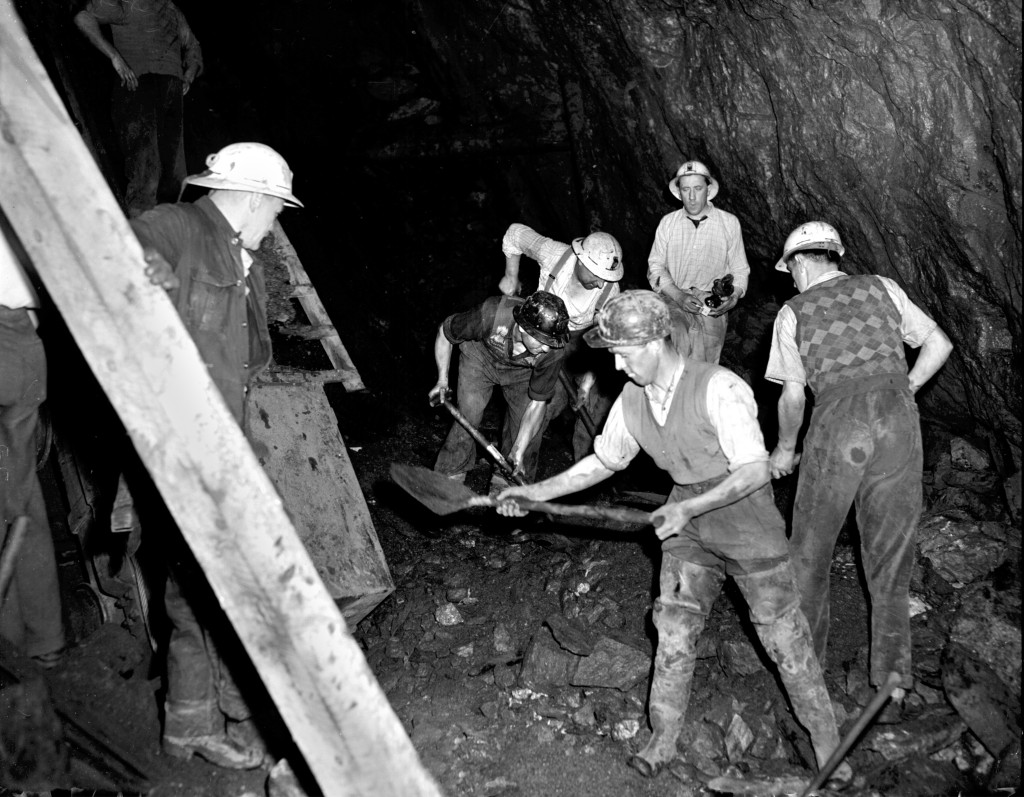

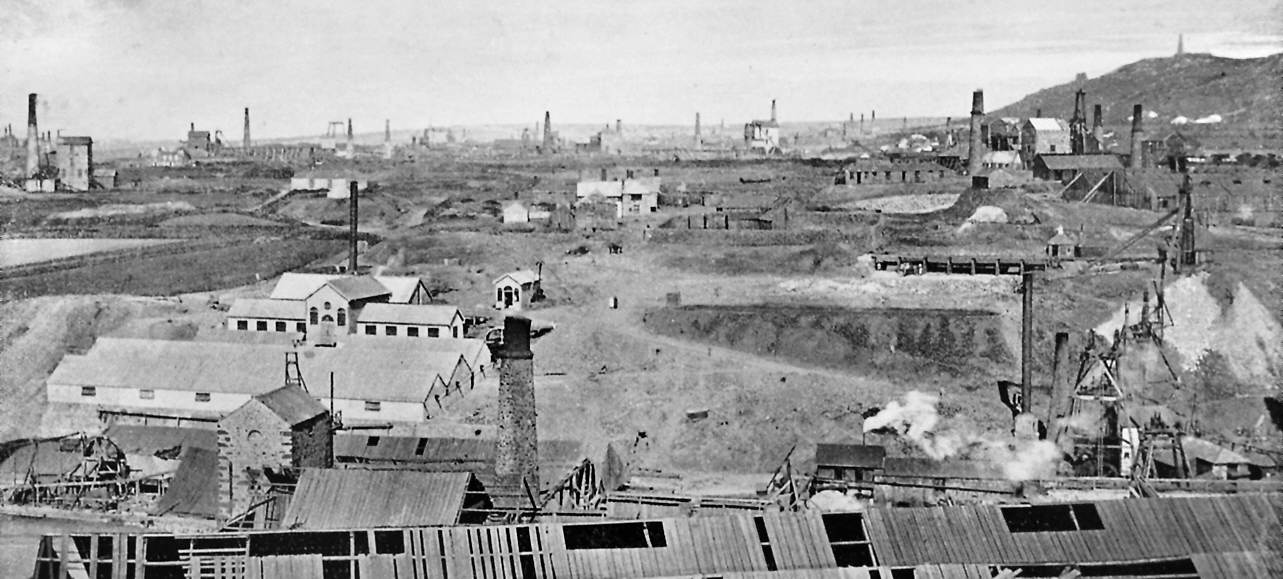

Brow Head – the headland itself – has been the subject of a previous post on Roaringwater Journal. It has a remarkably diverse history: not only is it the site of the Napoleonic-era signal tower, but of industrial and scientific activity. There are the substantial remains of a nineteenth century copper mine (photo above): I noted that the Mine Captain here was Hugh Harris from Cornwall – and wondered if he was a relation – until I read that he was dismissed as ...an incompetent authority…! Most interesting, perhaps, are the ruins of a signalling station set up by Guglielmo Marconi – established in 1901.

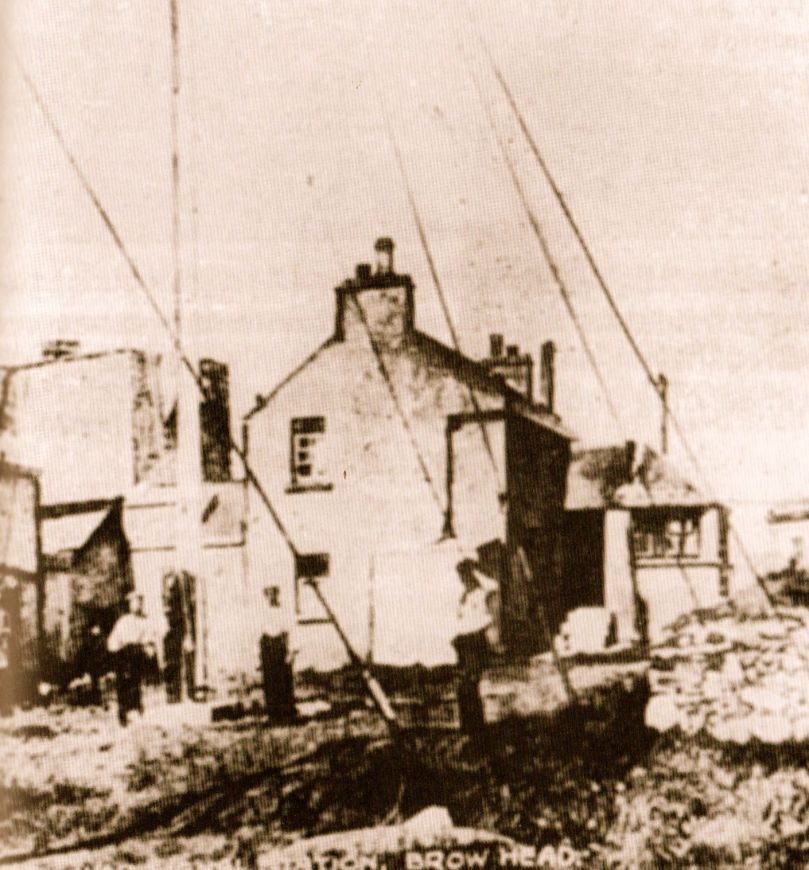

This photograph was taken in 1914. It shows the Marconi installation still in use: the signal tower is visible in the background, on the left. On the far right is a building which I take to be the electricity generating station, powering the telegraph. During the Emergency (1939 – 1945), a lookout emplacement was built to the south of the Marconi station: many of these were built around the coast, the majority sharing a site with a Napoleonic-era tower. Have a look here for more information on these comparatively recent structures.

For this excellent drone picture of the Brow Head site, taken in 2017, I am most indebted to Jennifer & James Hamilton, mvdirona.com. Jennifer and James are intrepid adventurers, travelling around the world on their Nordhavn52 vessel. It’s well worth going to their website to see what they get up to: it makes our own travels in the West of Ireland seem a little humdrum… On the right of the photo is the 1804 signal tower; on the left is the Marconi station with – just in front of it – all that is left of the 1939-45 lookout post. On the right in the foreground is the generating station shown in the present day photo, below. Note, also, in all these images can be seen the four-block supporting base for the Marconi transmission mast.

What happened to these buildings? Here’s an account I received from a RWJ correspondent (very many thanks, Rachel), after I had published an earlier post on them in 2014 – it is based on contemporary newspaper articles during the Irish War of Independence:

. . . Brow Head was destroyed on the 21st August 1920 at 12:45 – 1am, having been raided less than 2 weeks earlier on the 9th August. All reports mention the use of fire; only some mention the use of bombs. Explosives had, however, been stolen during the earlier raid on Brow Head (they were used for fog-signalling). Due to delays in reporting, some articles suggest different dates for these events but I’m fairly sure the 9th and 21st of August are the correct ones. 9th August: Armed and masked men raid the station and take stores of explosives, ammunition, and rifles. There are conflicting reports over whether any wireless equipment was taken during this raid. 21st August: Reports that all buildings at Brow Head (war signal station, post office, coastguard) destroyed, either by fire, or fire and bombs depending on the article. Some reports say 40 men were involved, some 70, some 150, some 150-200. These men had masks and were armed with revolvers to cover the three or four guards, they were described as young and courteous. The raid is said to have taken 5 hours; all Post Office equipment was taken away, as well as other stores. Other wireless equipment was smashed. The raiders helped the guards move their furniture/belongings out before setting fire to the buildings . . .

Rachel Barrett

So far we haven’t said much about the 1804 signal tower itself. Although ruined, it is a good example, reasonably stable, and has survived two centuries of severe Atlantic gales remarkably well. All the elements are recognisable: projecting bartizans, slate hung external walls for improved weatherproofing, an intact roof and distinct internal features – and a little enigmatic graffitti. Compare all these with the other towers in our series so far (there are links at the end).

If you set out to visit the Brow Head site on a good day, you can’t do better than to park at Galley Cove – at the bottom of the long, steep access road (and beside the Marconi commemoration board and sculpture by Susan O’Toole) – and then walk up. You will enjoy continuously changing spectacular views in all directions, and you will begin to see the signal tower above you as you approach the brow of Brow Head.

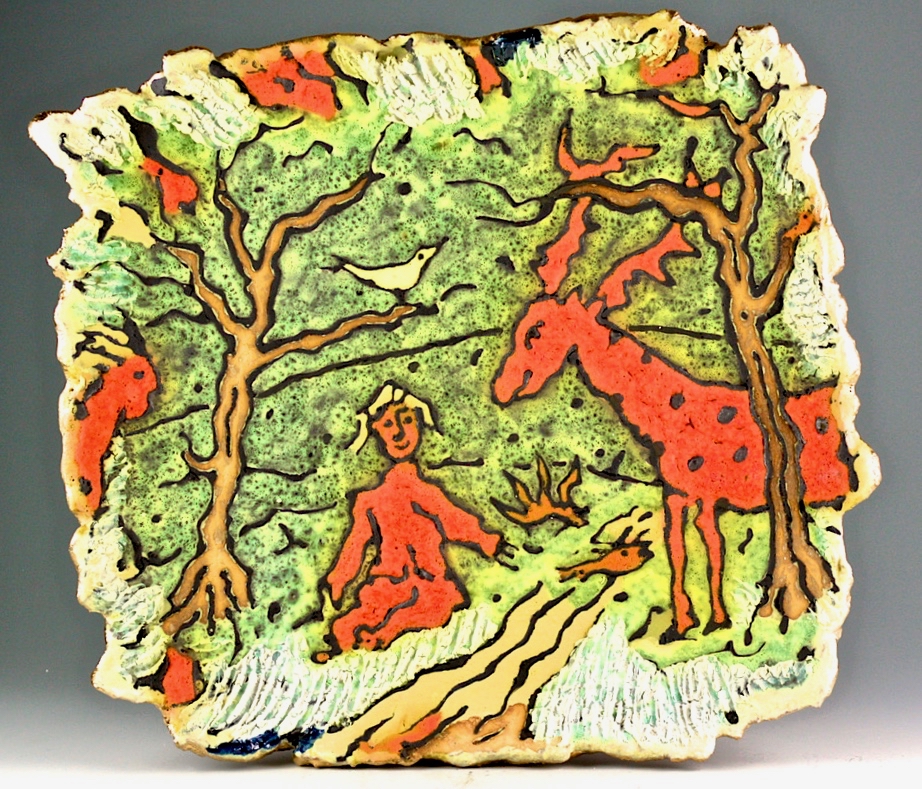

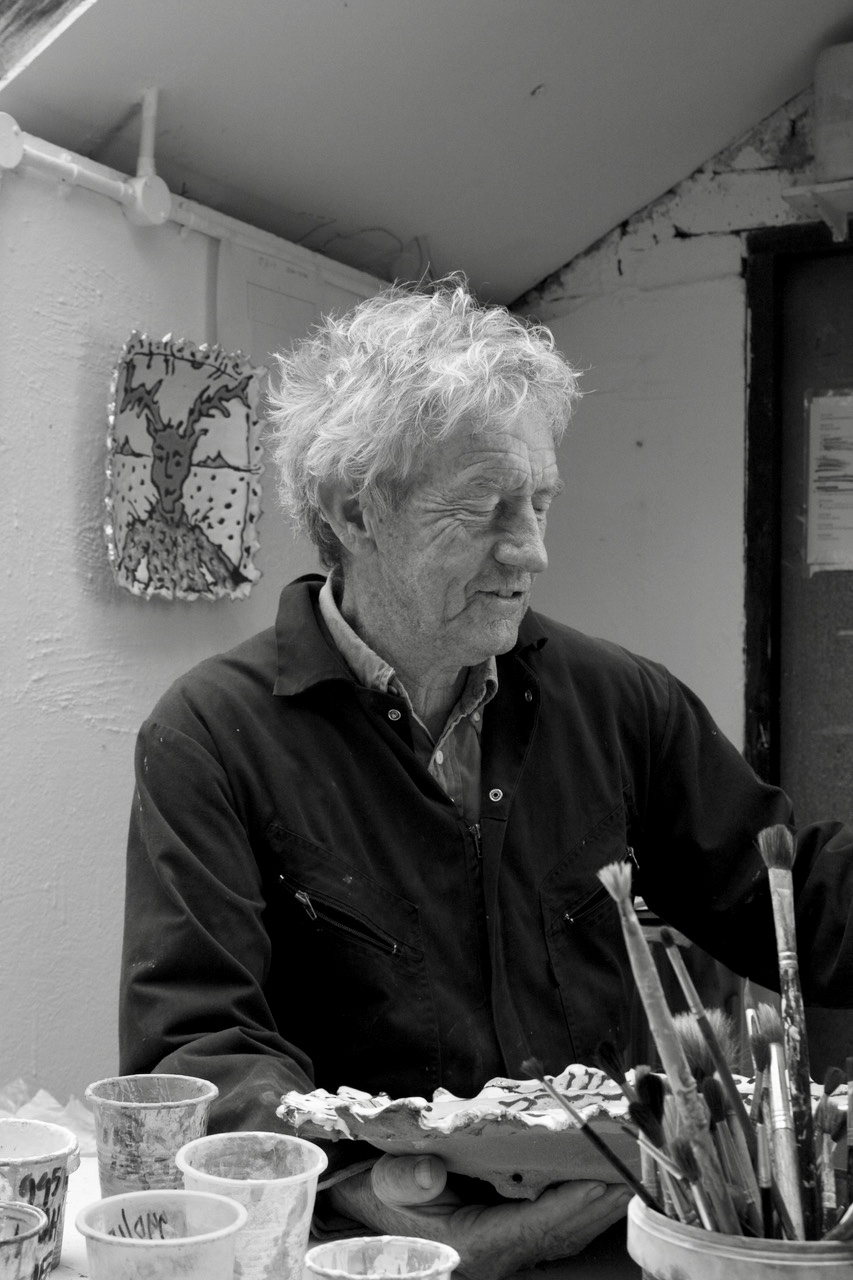

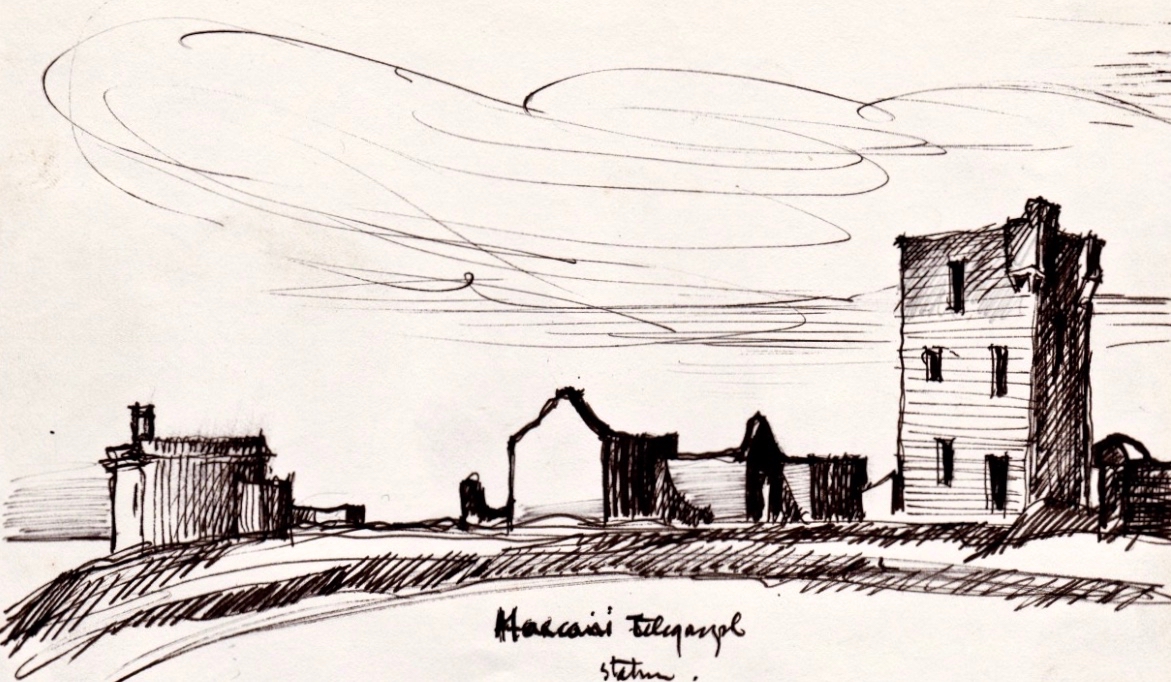

West Cork based artist Brian Lalor visited the Brow Head site with the Mizen Field Club in 1984. His sketch of the buildings is an interesting record as it appears to show, on the left, the 1939-45 lookout post intact (below). Very little remains now, 37 years later (lower). I wonder what led to this particular piece of destruction?

I’ll finish off with another sketch view of the Brow Head signal tower: this is by Peter Clarke, who runs the excellent Hikelines site. Many thanks, Peter.

The previous posts in this series can be found through these links:

Part 2: Ballyroon Mountain, Co Cork

Part 3: Old Head of Kinsale, Co Cork