My name is Thomas – William Thomas. When I’m at the mines they call me Captain Thomas – because I’m in charge! I’m visiting some of my old ‘haunts’, and thought you might join me, to see what a working day was like in ‘ . . . one of the wildest districts in the United Kingdom . . . ‘ – Gortavallig, on Rinn Mhuintir Bháire. I know you call this place The Sheep’s Head now: that amuses me. I’m always trying to pick up on the Irish words – it’s such a poetic language. My grandfather was a natural Cornish speaker, but the language was gone by the time I was born – it’s only used by the Bards nowadays.

That’s my house – above – in the townland of Letter East. That’s where I stayed with my family when I was Captain at Gortavallig. It was rough going when I had to get to the mine – a solid hour’s trek across rough country, and the same back again. As part of the work that we did while developing this mine we built a good ten miles of road, which helped with communications in that untamed north-coast country.

Come with me now on the way that leads down, firstly, to the cove at Bunown in Eskraha townland: there’s a slipway there, and a house where my assistant Superintendent, Mister Bennett, lodges. It was once a coast-guard station. This cove has also been the scene of some tragedies in your own time. There was the writer, James Farrell, who drowned while fishing off the rocks there in 1979. He’s buried beyond by the church of St James in Durrus, looking out forever over Dunmanus Bay. The sea is a dangerous element: I know, because I’ve had to work with it. But it’s your friend, as well as your foe. If it wasn’t for the sea we would have no chance of transporting ore from the remoteness of Gortavallig.

The rocks at Bunown – on a good day! James Gordon Farrell is buried facing the water of Dunmanus Bay at St James’, Durrus

They say that, wherever you are in the world, if there’s a mine – or even a hole in the ground – you’ll find a Cornishman at the bottom of it! That’s because pulling the metal out of the ground – and from the cliffs – and even from under the sea – was our lifeblood in that far western peninsula. But the land was ravaged. This scene (below) is where I grew up and learned my trade: Dolcoath, near Camborne in Cornwall, in its heyday one of the busiest mining areas in the world. My father James was agent there and I enjoyed ‘ . . . a liberal education and had the very great advantage of being taught dialling and the whole routine of the profession by the most eminent miners of the day and worked for several years as a tributer – an admirable practical school . . . ‘

I was pleased to get away from the noise, the grime and the stench of that place when I was called to Ireland with my own family in 1845, firstly to Coosheen on the Mizen – where I revived an ailing venture by successfully rediscovering the copper-bearing lode. After that I came here to the Sheep’s Head where the surveyors, travelling on board small inshore vessels, could see promising ore-bearing strata on the cliff-faces which were being eroded on this coastline. My job was to work those veins – a gargantuan one bearing in mind the uncompromising nature of the landscape and the remoteness of the geography.

Looking back across silver waters as we walk together on the rough pathway to Gortavallig: nature has been tamed by the fields that go down to the coast west of Bunown, whereas the way to the east is across rough, wild country

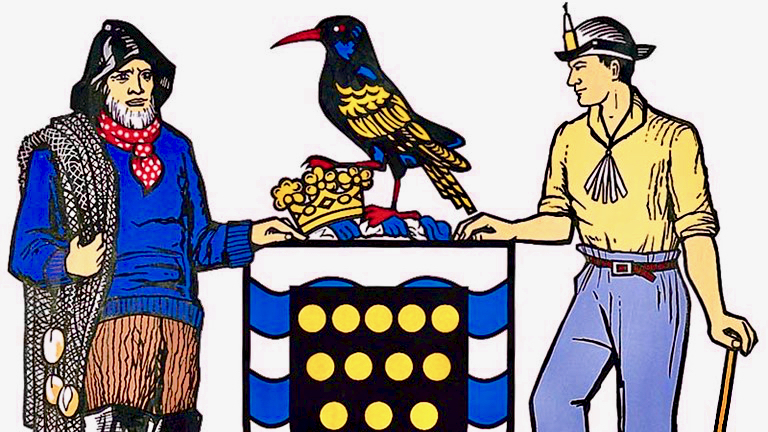

If you follow this path with me you will have to have good shoes and a steady gait, and the will to clamber upwards and downwards on sometimes steep and rough rock faces. But you will be rewarded by the remarkable vistas and the untamed surroundings. Your only companions will be the choughs: these sleek red-billed birds are a comfort to me as they have always been a symbol of Cornwall, sharing pride of place on that county’s coat-of-arms, together with an image of the Cornish miner! Did you know that the chough is the embodiment of old King Arthur, who is ready to rise again and save our nations in times of trouble?

A chough espied on our walk to Gortavallig, and the Coat-of-Arms of Cornwall which is shared between bird, fisherman and miner

After a vigorous hour’s trekking over the rough terrain we will catch our first glimpse of the mining works at Gortavallig: a row of small stone cottages perched on the cliff-top. This is known today as the Cornish Village, although it wasn’t just Cornish mine-workers who lived here. Good, strong Irishmen came to the place and earned their keep, and everyone here had to pay rent for the single-roomed lodgings. If there had been windows on the seaward side of these dwellings they would have enjoyed magnificent views, but we were more concerned at keeping out the extremes of the weather, and the few small windows only faced inland. There was plenty of ocean to be seen while you were working your hearts out to extract the minerals!

‘Cornish’ cottages close by the mine workings at Gortavallig

Once we have passed by the cottages we find ourselves traversing a sheer cliff edge. Below us the sea roars, but it’s down there that we built two quays, one 73 feet long and 40 feet high, the other 92 feet long and 36 feet high and, at the base of the cliff, a dressing floor 180 feet long and 50 feet wide, while above it we put in a stone dam and sluice so that we could wash the ore. Water was such an important element to us: in Cornwall we used its power to turn wheels and drive machinery such as crushers. We were never short of it here in Ireland.

Hold on to that rope or you might go over the edge!

Now, of course, on an idyllic day of blue sky and sunshine, you couldn’t find a place more picturesque, peaceful and redolent of nature’s beauty, but imagine what it was like in my time when men, women (we called them Bal Maidens in Cornwall) and children laboured long hours to bring out the precious ore and break, dress and prepare it for market: there was always the movement of ropes and machinery as trucks were pushed out of the mine-galleries on the rail-way, and figures constantly toiled up and down the precipitous rough stepways to and from the quays so far below. Although built in as sheltered a position as possible, they were constantly battered by heavy swells and breakers. In fact, they have now disappeared altogether.

Finola braves the cliff edge to get a view of the site of the old quays below, accessed by the rough and steep stone lined path

If we go up to the hillside above the mine workings we can look out over the reservoir, and we can also see the fenced-off openings of shafts. Most of the engineering took place, of course, underground: hard work in restricted spaces. We did our best to ensure safety, but there were accidents.

A lot of people have said that our mine was a ‘failure’, but I wouldn’t necessarily share that view. In May 1847 I presented my first report to the directors of the company:

. . . We have set bounds to the Atlantic waves, for though they lash and foam sometimes over craggy rocks, our works have withstood the furious storms of two severe winters. A complete wilderness and barren cliff, which had been for past ages the undisturbed resort of the Eagle, the Hawk and Wild Sea Bird, has by our labours for the past 16 months been changed into a valley of native industry, giving employment, food, and comfort, to numbers of the hitherto starving, but peacable inhabitants. We have in the course of 16 months, with an average number of 24 miners, whose earnings ranged from 9 shillings to 12 shillings a week, explored 174 fathoms of ground. We have also employed about 26 surface men, at the rate of 10 pence and one shilling a day . . .

In May 1848 the SS William and Thomas collected 88 tons of copper ore from the quay of our mine at Gortavallig. It sold for £269 14s in Swansea. Yes – it was the only shipment that the mine ever exported, but it gave employment and food to families in one of the remotest areas of the West of Ireland during the ‘Great Hunger’. In my time at Rinn Mhuintir Bháire I was able to set up – at my own cost – the Coosheen Fishery Association over on the Mizen, which also helped with food production through those bad years. With my brothers Charles and Henry, and my son John, we helped to bring industry to the remote fastnesses of West Cork and Kerry – including the mine at Dhurode, on the Mizen. I feel satisfaction that our lives have benefited our neighbours here in these far western peninsulas which bear such a similarity to our own native Cornwall . . . Now you will want to return to civilisation: thank you for your company and mind your step – I think I’ll rest a while here pondering on old times with my pipe and tobacco.

Captain William Thomas possibly in 1843 (left) and right, with one of his daughters in 1852. The latter photograph was taken by Hastings Moore in Ballydehob

From the Skibbereen Eagle, 7 June 1890:

Died, May 22nd at Coosheen, Schull, William Thomas, of Bolleevede, Camborne, Cornwall, aged 82 years, manager of mines in Cork and Kerry for nearly 50 years. He truly believed in Irish men and Irish mines. He wrote and spoke on their behalf to the utmost of his ability . . .