it’s not just for long walks – the Sheep’s Head is also perfect for wandering with intent, having, as my father used to say, a dander. Our trip there this week, in the excellent company of Amanda and Peter, was that sort of day, where we drove around and dropped in and out of interesting places. Amanda and Peter Clarke, our regular readers will know, are the couple behind Walking the Sheep’s Head Way, so who better to have as companions and guides for a day of exploring. Amazingly, given all the time we’ve spent there, only one of our stops was familiar.

Our first stop was a curious stone overlooking Dunmanus Bay. Known as the Giant’s Footprint, the local legend tells a familiar story about two giants throwing rocks at each other. This must have been a mere pebble, because one of the missiles became the Fastnet Rock. Footprint stones are also associated with inauguration sites, where kings were acclaimed in early medieval society. (See the comments section below for a link to an amazing piece of art from our friend, the acclaimed photographer EJ Carr, who used this stone in his fantasy photography piece on the Arthurian legend – follow the link in the comment to view his images.)

Being with Amanda is always a great opportunity to visit a holy well and we had never been to Gouladoo. It also ticked a box for me as I’ve been wanting to visit promontory forts. The holy well first – it’s a Tobar Beannaithe, a Blessed Well, not associated with any particular saints. Amanda’s research revealed that it did have a particular purpose, though – girls would visit to pray for a husband. Read Amanda’s comprehensive account here.

Because this is on the Sheep’s Head Way, the route is signposted and maintained. The well itself has a cup thoughtfully provided so you can have a drink if you dare. The path down to it has been carved out of the hillside and roughly paved, indicating that this was a site to which many people once came.

If you turn your back to the holy well, the promontory fort is straight ahead of you.

Where you have a promontory jutting out into the sea it’s easily fortified by building banks and ditches at the neck. Promontories with narrow necks were usually chosen, as being easiest to defend, and archaeological evidence suggests that some were in use as early as the Bronze Age but most evidence of occupation dates to the Early and Later Medieval Period (400 -1500AD).

As promontory forts go, this is a classic – a narrow neck with evidence of walls across it, steep cliffs on all sides, and a flat and verdant area in the middle for houses and cattle. This one has an added feature – sea arches underneath! The sea arches mean that this may eventually become an island.

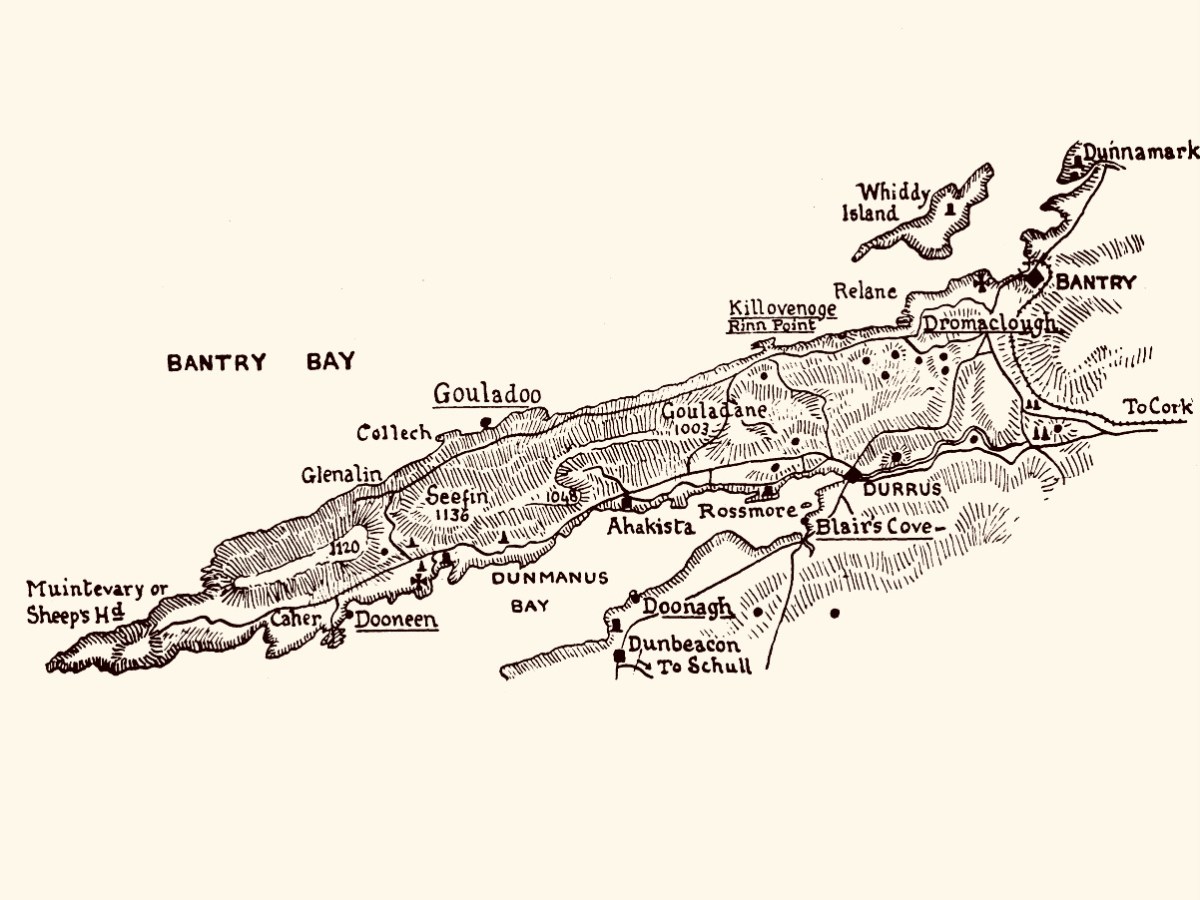

The antiquarian Thomas J Westropp set out to visit all the promontory forts along the Beara and Sheep’s Head in or around 1920 and has left us his account, written over three articles in the Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. Gouladoo, as his map shows, was one of his destinations.

Here is his description of the fort as he found it then.

Far to the west of Rinn, in Kilcrohane, is a remarkable fortified headland of dark grey slate, up tilted and separated from the mainland by a gully. This is spanned (like those at Doonagh and Dursey) by a natural arch. The adjoining townland is called Dunoure, but no fort is known to have existed near this, so perhaps that name refers to Gouladoo. The arch is lintelled, like a great Egyptian pylon, and is 15 ft. or 16 ft. wide at the gully. The neck is wider to the landward, and was strongly defended. First we find a trace of a hollow or fosse; then the foundation of a drystone wall 82 ft. long (E. and W.); behind, a natural abrupt ridge forms a banquette over 4 ft. high; the wall is about 12 ft. thick, the terrace 12 ft. to 15 ft. wide. Beyond this the neck was enclosed all round by a fence about 6 ft. thick. The whole work measures about 80 ft. each way. As at Doonagh, I think that the line of debris on the peninsula along the edge of the chasm is a trace of a wall, and that the bare slope behind it was stripped by a landslip. The whole is tufted with luxuriant masses of rich crimson heather.

The Promontory Forts of Beare and Bantry: Part III, Thomas J Westropp

The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 1921

It’s quite difficult to see those features now, although there is a piece of the wall remaining, and what must be his ‘terrace.’

There are other compensations to visiting a site like this – those sheer cliffs which provide such an impregnable defence for the fort, also host many gulls in nesting season. The Bluebells and Sea Campion were abundant there too.

Westropp wrote his article, The Promontory Forts of Beare and Bantry, over several issues of the Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, and maybe it would be fun to retrace his steps a hundred years later to see what’s on the ground now – what do you think?

From there it was off to the Mass Rock at Glanalin, an easy walk down from the Pietà in the pass above Kilcrohane. It’s a particularly lovely walk to this mass rock (above), and in May the spring flowers are everywhere, especially St Patrick’s Cabbage, one of the group of plants known as the Lusitanian Flora, that only grows here and in Iberia.

And finding a lone Heath Spotted Orchid (above) was a real bonus too!

By sheer coincidence we were there on the same day, May 17th, when Mass was celebrated here in 2000 in remembrance of the ancestors who worshipped here.

Our final stop of the day was another site new to us, the Marriage Stone! That’s Peter’s sketch of it above, from his Hikelines Blog. Tradition has it that people would get married here, as described by local farmer Jack Sheehan:

The hole in the stone is narrow on one side and wide at the other. The man had a bigger hand and he put his hand through the big side and the woman put her hand through the narrow side. They made their promises when they put their hands through the stone

Of course we all had to do it!

There was a ring fort nearby – actually described as an enclosure in the National Monuments records – but over the years it has been disturbed to the point where it is hardly recognisable. Perhaps it is this site that gave its name to the townland, Caherurlagh. A caher is a stone fort and so the townland name means Fort of the Slaughter. Perhaps there are some aspects to the history of this area into which we should not delve too closely.

I highly recommend a day like this on the Sheep’s Head, with Walking the Sheep’s Head Way as your travelling companion, and channeling the spirit of old Thomas Westropp. I will leave you with what he had to say about the views north to the Beara as he journeyed along the north side towards Gouladoo

We pass beneath the beautiful woods of Bantry House and the picturesque old graveyard, where the Franciscan Friary once stood erected by O Sullivan in 1330. We reach the shore out of a maze of low green hills, several with ring forts on their summits, near Dromclough. Thence on past Rinn Point and up the lofty road, often unfenced and narrow, along the edge of cuttings and precipices to Gouladoo and Collack. The sweep of the high mountains in Beare and those inland heights towards Muskerry is magnificent as seen across the great bay. From Black Ball Head and Dunbeg past flat-topped Slieve Miskish and the great domes of Hungry Hill and the Sugarloaf, on to the shapely cone of Mullach Maisha, the stately range extends.