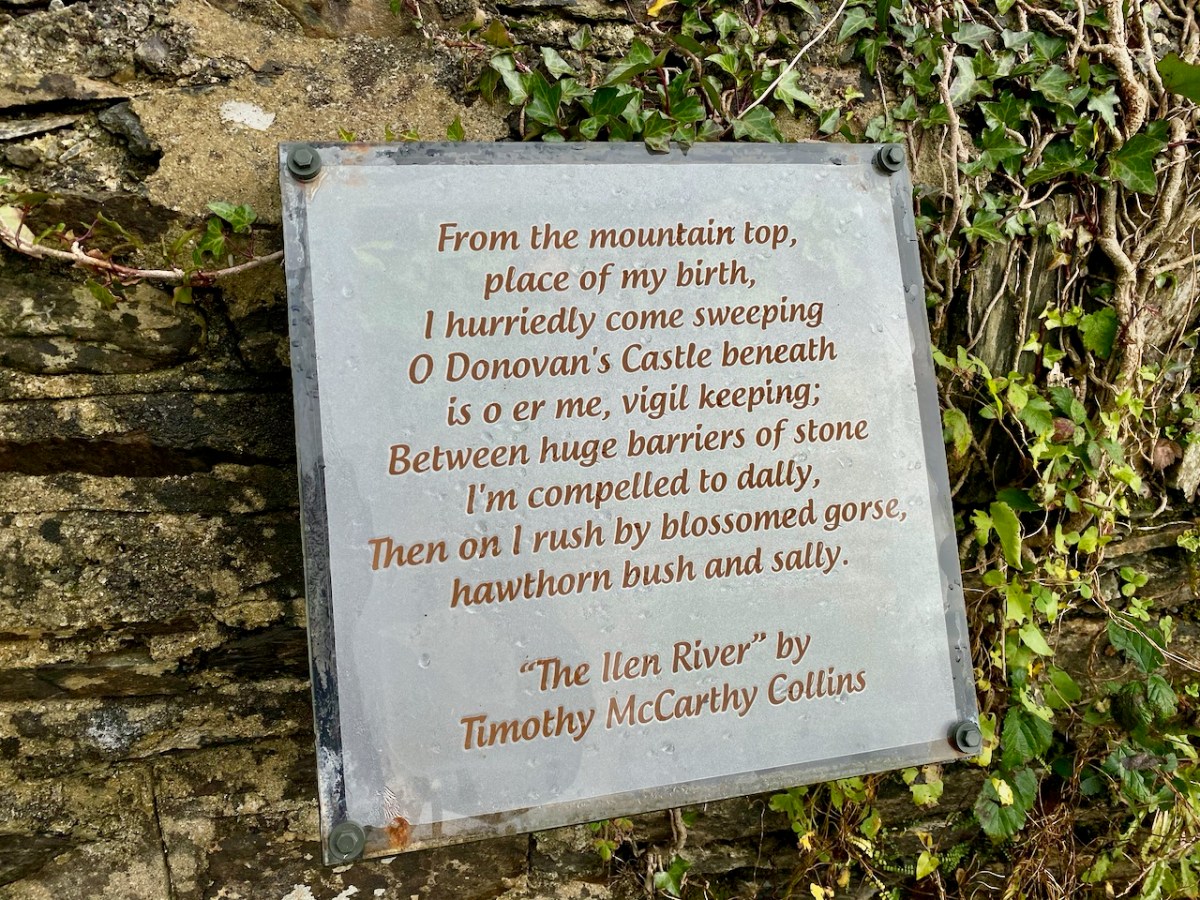

There’s a walk that goes down from Castledonovan to Drimoleague: it follows an ancient mass path and much of it is right alongside the Ilen River. At its northern end there is a section known as the Deelish Cascades: this is geologically fascinating, and gives us some insights into how our West Cork landscape was formed thousands of years ago.

. . . The oldest rocks exposed in West Cork are of Devonian age (410 – 355 million years ago) . . . These mostly red and green sandstones, siltstones and mudstones were deposited on a continental landmass in a low latitude desert or semi-arid environment. The sediments were deposited from rivers, whose flow was dominated by flash-floods fed by episodic rainfall, which originated predominantly from mountainous areas lying to the north which were were formed during the Caledonian Orogeny (mountain building event) in latest Silurian and early Devonian times. The environment was perhaps similar to the present day Arabian desert. This “Old Red Sandstone” continent extended over what is now northwest Europe. In Cork and Kerry these sediments accumulated in a large subsiding trough (the Munster Basin), resulting in one of the thickest sequences of Old Red Sandstone encountered anywhere in the world (at least 6km thick) . . .

Geology of West Cork, M Pracht and A G Sleeman, geological Survey of Ireland 2002

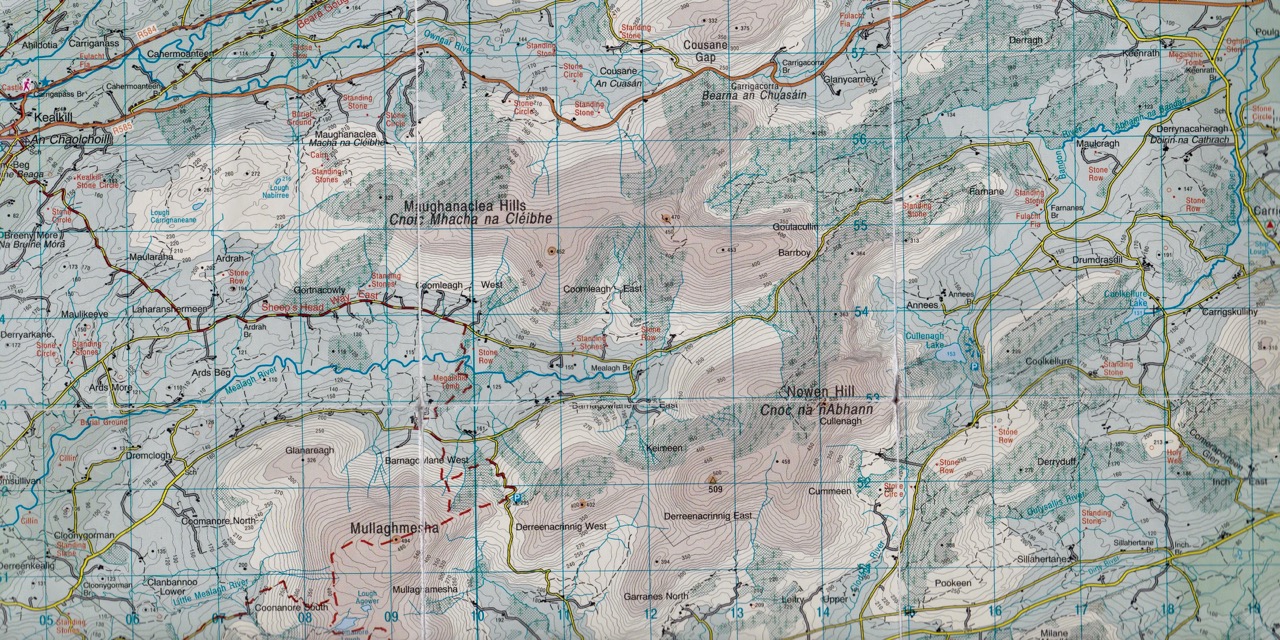

I have marked on this Geology Map the course of the Ilen River from its source on Mullagmesha Mountain to the tidal estuary which begins at Skibbereen. The map shows the ‘grain’ of the various faults which run SW to NE over the terrain: the river generally flows perpendicular to these faults, and the ‘grain’ is clearly seen in the exposed river bed running over the Deelish Cascades.

Praeger usefully simplifies the geological definition of the landscapes (for more on Praeger see Finola’s complementary post today):

. . . The story which geology tells as to how West Cork and Kerry got its present form is interesting, and I shall try to tell it in non-geological language. Towards the close of Carboniferous times – that is, after the familiar grey limestone which covers so much of Ireland and the beds of sandstone and shale which succeeded it were laid down on an ancient sea-bottom, but long before the beginning of the Mesozoic period, when the New Red Sandstone and white Chalk were formed – the crust of the Earth in Ireland and beyond it was subjected to intense lateral squeezing from a north-south direction. This forced it into a series of great east-west folds, thousands of feet high from base to summit – the Carboniferous beds on top, and below them and following their ridges and hollows the massive strata of Devonian time, and other deeper-buried systems. A series of pieces of corrugated iron laid one over the other will illustrate what happened. The folding was developed particularly conspicuously in the Cork-Kerry area. What we see is the result of this ancient crumpling, now greatly modified by the effect of millions of years’ exposure to sun and frost, rain and rivers . . . The more resistant slates, carved into a wilderness of mountains, still tower up, forming long rugged leathery ridges. A sinking of the land has enhanced the effect by allowing the sea to flow far up the troughs. That the ridges were longer is shown by the high craggy islands that lie off the extremities, and continue their direction out into the Atlantic . . .

The Way That I Went, Robert Lloyd Praeger, Methuen & Co London, 1937

While the upheavals of far-off eras reaching back millions of decades certainly laid the foundations of our landscape, the geological events which actually honed the shaping of the terrain as we see it today are far more recent – the ‘Ice Ages’ which developed only 30,000 years ago and had receded by about 10,000 BC. During that time sea levels fell and then rose again, and the topography and shoreline of the island with which we are familiar today was established. The ice sheets covered most of the land and were up to 1,000 metres thick. As they melted, glaciers fell away from the highest points and carved fissures into the slopes, creating valleys and rivers. One of the most extensive ‘local’ ice-caps was in south-west Munster where a ‘Cork-Kerry’ glaciation, centred on or close to the Kenmare river, developed independent of the general ice sheet. Our own ‘Sweet Ilen’ was a consequence of the ice movement, and the rock formations that we see in the Deelish Cascades are good evidence of these modern geological events.

All the way down the Cascades you will see evidence of the scouring of the rocky river bed, and huge ‘erratic’ boulders that have been carried from the mountain-top on the ice flow, to be deposited randomly – and picturesquely – in the torrent. Of course, you don’t have to know about geology to appreciate the walk: you are free to explore the well kept path and delight in this West Cork experience which has been laid out for us all through the mighty efforts of the Drimoleague Heritage Walkways and the Sheep’s Head Way.

Previous episodes in this series: Sweet Ilen : Sweet Ilen – Part 2 : Sweet Ilen – Part 3 : Sweet Ilen – Part 4 : Sweet Ilen – Part 5 : Sweet Ilen – Part 6