The popular Atlas Obscura defines itself as the definitive guide to off-the-beaten-track and little known wondrous places. So we’ve captured that idea and, as our Christmas present to our readers, bring you our own carefully-curated, slightly eccentric, Roaringwater Journal Guide to West Cork’s Hidden Wonders. Robert’s selection is here. No well-know tourist spots for these posts! No car parks and visitor centres! You may need wellies for some, a good map for others, and, although all are accessible, some may require permission.Each place I recommend will link to a blog post with more information. As an example, Sailor’s Hill, just outside Schull (above) is an easy walk and look what you get at the top!

This is the view from Brow Head, looking back towards Crookhaven, and Mount Gabriel in the distance. Brow Head is much less visited than Mizen Head, but just as spectacular

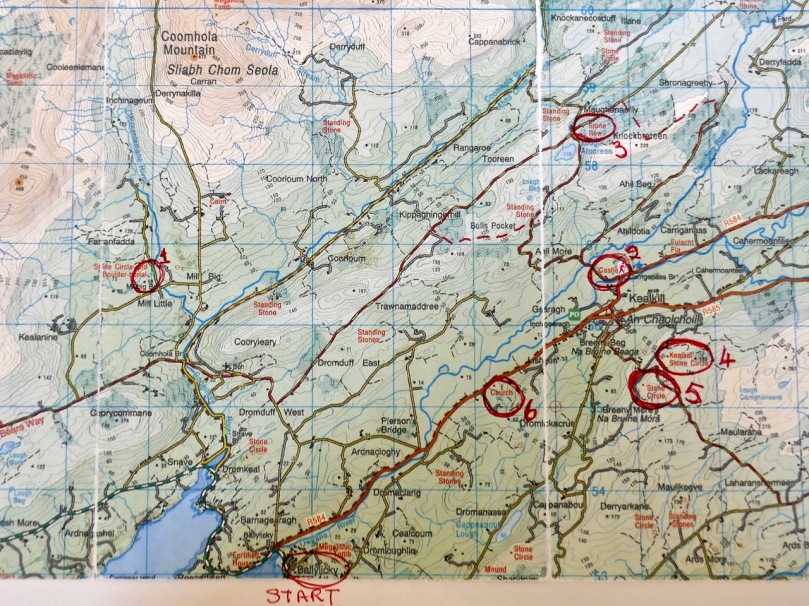

I’m going to start with some archaeology and a couple of spectacular sites. The first is the Kealkill Stone Circle – but this isn’t just a stone circle, it’s a complex of monuments that includes a five-stone circle, a radial cairn (very rare in this part of the world) and two enormous standing stones. The views are immense in every direction, and the site is easy to find.

We all know about Drombeg – and we love it when the sun goes down at the midwinter solstice, and even when it doesn’t. But fewer people know about another stone circle, equally spectacular, with a spring equinox orientation. It’s called Bohonagh and it’s quite a complex. First of all, there’s a boulder burial, with quartz support stones and cupmarks on the boulder. Then there’s a cupmarked stone, partly hidden in the brambles between the boulder burial and the stone circle. Finally, there’s the circle itself, almost complete, with views in all directions.

Equinox sunset at Bohonagh

We were lucky to have a session there one equinox, and another one with Ken Williams of Shadows and Stone. For access, park just off the main road, across from the salmon coloured house 4.5km east of Rosscarbery and walk up the farm road to the barns and from there to the top of the hill. This is a working farm – please close all gates and be respectful of animals!

Maughnasilly Stone Row broods on the hilltop

A stone row to round out the archaeology sites – this one is at Maughnasilly and I chose it because it’s been excavated, so there’s an informative sign, access is easy and it’s a beautiful, atmospheric site, overlooking a small lake. The row has been calculated to have both lunar and solar alignments.

And from the ground…

A couple of churches now, beginning with the Church of Ireland Church of the Ascension in Timoleague. This is one of those places that is dripping with unexpected stories. As soon as you go through the door your jaw will drop – the whole church, floor to ceiling, is covered in mosaic, partly paid for by an Indian Maharajah. Read the story here and here – and look carefully at the stained glass windows, some of them are among the oldest stained glass we have in Ireland. The key used to be at the grocery store on the main street, but I’m not sure where it is now, so you may have to ask around. Let us know if you find out.

The interior of the church, and one of the beautiful Clayton and Bell windows

You may wonder at my next choice – it’s not everyone’s cup of tea – but the modernist church in Drimoleague is the work of Frank Murphy, the architect hailed as Cork’s ‘Unsung Hero of Modernism’.

I love the spare minimalist space, very rare in West Cork, but it’s the stained glass windows that drew my attention. It’s not that they are particularly beautiful or skilfully done: they’re by the Harry Clarke Studios long after Harry himself had died. It’s that they fascinate me as a social document – they are, in fact, a prescription for how to live your life as an Irish Catholic in the 1950s. As such, they will resonate with anyone of my vintage. Research by the brilliant young scholar, Richard Butler, has revealed that the design was practically dictated by Archbishop Lucey, still a name to invoke an image of the all-powerful churchman of the 20th century.

And a final church, but this one strictly for the windows. (No – not St Barrahanes in Castletownsend for the Harry Clarkes – everyone knows about them already, and this is a selection of lesser-known wonders.) Do NOT go through Eyeries, on the Beara Peninsula, without stepping into the little church of St Kentigern. Here is where we were first introduced to the work of the stained glass artist, George Walsh.

The Annunciation and Nativity window

The Annunciation and Nativity window

When Robert wrote his original post, we couldn’t find out much information on George Walsh, but now he has become a friend and I have written about his work for the next issue of the Irish Arts Review (due out in March, 2019) and spent many happy hours photographing his windows and his artwork around Ireland. It’s bold, graphic, modern and incredibly colourful, and the windows in Eyeries, along with the religious themes, tell the story of Ireland and the Beara through time.

Some places to visit now for a good walk or a swim. First, one of my favourite walks is to hike up to Brow Head, at the end of the Mizen Peninsula (you can drive up too, but pray you don’t meet a tractor coming down) and then walk out to the end of the Head (see the second photo on the post for the view from the top of the road). Stop first to explore the ruins of the old Marconi Station – there’s also a Napoleonic-era signal station and a WW2 Lookout Post. Then wander through the heather and the low-growing gorse until you get to the part where the sea is crashing below, with vertiginous drops off either side. I will leave it to you how far you go from there!

Brow Head showing the signal station and Marconi station silhouetted against the evening sky

Although Barley Cove is well known, Mizen locals love Ballyrisode Beach for a swim or a lounge in the sun. White sand, sheltered bays, and water warmed by running over the shallow bay. The final little beach holds a secret – a Bronze Age Fulacht Fia or Water-Boiling Site, that Robert and I recorded for National Monuments this summer. It was an exciting find, hiding in plain sight. The beach has an association with pirates too!

Ballyrisode Beach – yes, the water really is this colour. The three sided rectangular stone thing is the fulacht fia

The final choice for a walk is Queen Maev’s tomb, a short hike up from Vaughan’s Pass car park, up behind Bantry. For this photograph I am indebted to Peter Clarke, of the wonderful Hikelines blog. He and Amanda (with whom we have explored SO many holy wells) were our companions that day. When you reach the top there is a small wedge-tomb, but this is one place where the journey is the real story, with the Mizen, the Sheep’s Head and the Beara all spread out before you.

Photograph © Peter Clarke

I leave you with a detail from the George Walsh windows in Eyeries, together with the poem the scene is based on, Pangur Bán, written in the 9th century by an Irish monk labouring away in a scriptorium in Europe. Here is the poem read, at a memorial service for Seamus Heaney, first in the original Old Irish and then in Heaney’s translation.

Merry Christmas from us! If you live here, get out and about this year to some of our picks, and if you don’t, come see us soon!