We have written previously about the sacred site reputed to be the “Centre of Ireland”. In other words the midpoint of the country: that’s the whole of the island of course – the division into Ireland and Northern Ireland is an artificial designation barely a century old. It’s a many-centuries-old tradition that the Hill of Uisneach, in Co Westmeath, is regarded as the geographical centre of this whole island and has been regarded as a major ritual site for the assembly of the ruling families and debate on the lore of the land.

We visited the hill in October 2016, while preparations were being made to celebrate autumn festivities there. In the picture above, you can see the Godess Eriu being decorated. It was she who gave Ireland its name – Eire. Before you read on about Uisneach’s other claim to fame, have a look at my post from six years ago, here. My friend Michael read this post and sent me a fascinating article on the subject of ‘the geographical centre of Ireland‘. Please read it – and, if you understand the technicalities of the process, please let me know!

. . . The calculation to find the exact geographic centre of Ireland was carried out by OSi using the most up-to-date, openly available geospatial data and widely used geographic information system (GIS) technology. Specifically, OSi used Esri’s Mean Centre Point tool in ArcMap and features data for the Republic of Ireland from its own open-source data set, OSi Admin Areas Ungeneralised, as well as an openly available OSNI Largescale County Boundaries data set from Land & Property Services of Northern Ireland (LPS). The Northern Ireland features were reprojected from an Irish National Grid coordinate system to line up with the OSi features for the republic of Ireland (ITM), enabling the datasets to be processed together. In just a few short minutes, the coordinates 633015.166477, 744493.046768 were revealed, providing one scientific answer to an age-old question . . .

Ordnance Survey of Ireland Data February 25th 2022

To get to the salient point, the Ordnance Survey of Ireland is rejecting tradition in favour of science! They claim the true centre of this island is a little distance from Uisneach:

. . . According to a new calculation from Ordnance Survey Ireland (OSi), the centre of the island of Ireland actually lies at the Irish Transverse Mercator (ITM) coordinates 633015.166477, 744493.046768, near the community of Castletown Geoghegan, between the towns of Athlone and Mullingar. This scientifically-calculated centre point is situated, as the crow flies, approximately 31km east of the Hill of Berries, 35km east-south-east of the townland of Carnagh East and a mere 5km south-east of the Hill of Uisneach, Loughnavalley, Co. Westmeath . . .

Ordnance Survey of Ireland Data February 25th 2022

Whilst acknowledging that ” . . . Over time, new data, advancing technologies and new techniques could generate different versions of the truth . . .” the Ordnance Survey throws out a challenge to tradition. I’m throwing that challenge right back!

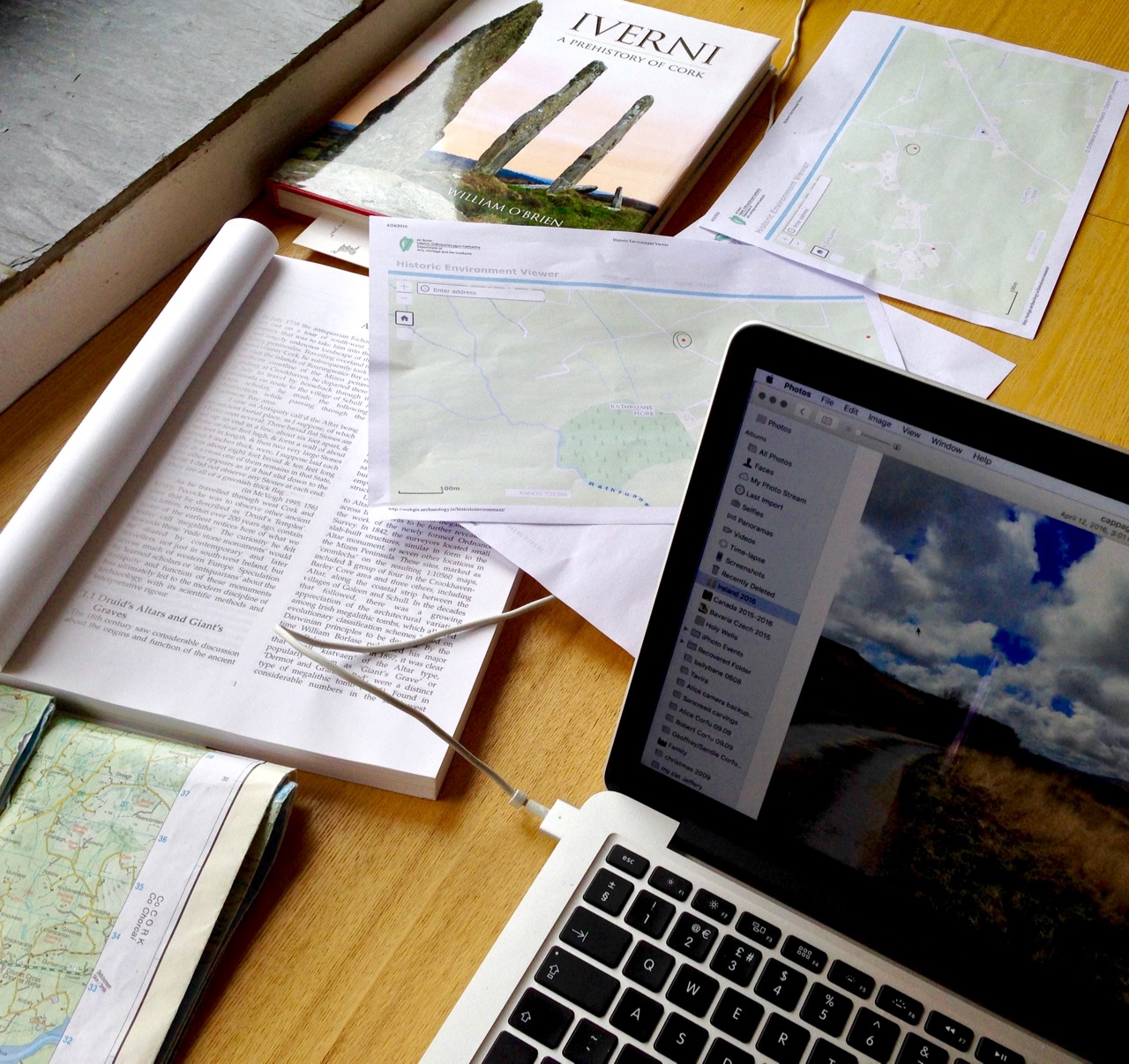

If I was going to set out to find the geographical centre of Ireland, I would take a large map and pin it up on the wall:

Then I would throw a dart at it – aiming for the middle! I’d get somewhere near, for sure. In fact, there’s a little red dot on this map – just under Mullingar: this is where Uisneach is located. But, if you want something more technical, might you work out a centre based on distances from the extremities? Here are some possibilities:

However, this map does rather show up the inadequacies of this methodology! So, what does Uisneach have to recommend it – and justify the long-held tradition? Well, it does have a large rock, known as ‘The Cat’s Stone’ . . .

This enormous erratic is also known as ‘The Navel’, which is quite a clue as far as I’m concerned. so, how might our ancestors have come to this conclusion – by maps?

This is known as Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland. It is often said to date from 140AD, but is in fact a Greek copy dating from around 1400AD. Ptolemy did produce maps: he didn’t visit the distant locations, but based his projections on information recorded by sailors who explored the corners of the world.

This map of the British Isles has a similar heritage. Again, you could throw a dart at the centre of Ireland on either of these maps and get pretty close to Uisneach!

This map is somewhat later (1325) and is far more accurate. It’s interesting to me that it shows the fabled islands of Brasil and Demar, mentioned in accounts of St Brendan’s sixth century voyage. We can also wonder at the fact that the only place marked on the south western part of Ireland here is Dorsie (Dursey). But none of these early maps – while fascinating – can support the observation that anyone living in those days could calculate the ‘centre’ of Ireland by looking on a map!

Examining the area around Uisneach on the earliest Ordnance Survey maps (above) gives an idea of the earthworks which were considered important to record in the area. I’m wondering what the ‘cave’ is that’s indicated lower right in the top extract?

Interestingly, in the UK, the village of Meriden is traditionally said to mark the centre of England. But the UK Ordnance Survey has also challenged this.

Preparing for the autumn ceremony at Uisneach Hill, above. We can ponder and argue on the claims to be able to locate the centre of an island (and it’s certainly fascinating to do so) but – while thanking my friend Michael for stimulating this thought process – perhaps the UK Ordnance Survey should be given the final word here:

. . . The truth is, that there can be no absolute centre for a three dimensional land mass sitting on the surface of a sphere and surrounded by the ebb and flow of sea water. If you consider the movement of tides on a beach, the shape of the object will change on a constant basis. Another contributing factor is how far you consider the coast to stretch up river estuaries. Different projections, scales and methods of calculation will all produce different results . . .

Ordnance Survey UK 2014