I was excited to be travelling to one of Ireland’s oldest – and most important – pilgrimage sites. Finola studies stained glass windows and their artists, and she knew that some particularly impressive Harry Clarke windows can be seen in the Basilica on Station Island, Lough Derg, in County Donegal. The roof of the Basilica, completed in 1931, towers over the island in the picture above, taken from the quay at Ballymacavany. Finola obtained special permission for us to visit the island to view and photograph the windows, after the main pilgrimage season was over: her account of them will appear in Roaringwater Journal in the near future.

It’s salutary to learn how many people and families we know have taken part in the pilgrimage at Station Island. It’s a particularly austere experience, involving a three day cycle of prayer and liturgies, bare-footed and with very little food or sleep. Finola’s father undertook the pilgrimage in the 1950s: the photograph above was taken at around that time, when pilgrims were ferried over in large open boats once rowed by eight oarsmen and subsequently motorised. One of these historic boats is kept on display at Ballymacavany (below). Nowadays the journey is made in a modern covered launch, as seen in the header photo.

Records of the number of pilgrims who travelled to Station Island have only existed in comparatively recent times. The peak seems to have been just prior to the famine around 1846, when over 30,000 went there in one season. The drawing above is by William Frederick Wakeman, who was a draughtsman with the Ordnance Survey of Ireland, and was probably made at that time. Through the twentieth century numbers seldom fell below 10,000 pilgrims each season, but in many years was considerably more. This news item from the RTE Archives demonstrates the strength of the pilgrimage in the year 2000.

The island’s long history takes us back to the time of St Patrick. Despairing at the arduousness of persuading the Irish people to accept his Christian teachings he appealed to God to help. The story is admirably recounted by Dr Peter Harbison, Honorary Academic Editor in the Royal Irish Academy:

…St Patrick … was having difficulty convincing the pagan Irish of the 5th century of the truth of his teaching about heaven and hell; they were not prepared to believe him unless one of them had experienced it for themselves. To assist Patrick in his mission … Christ showed Patrick a dark pit in a deserted place and told him that whoever would enter the pit for a day and a night would be purged of his sins for the rest of his life. In the course of those twenty four hours, he would experience both the torments of the wicked and the delights of the blessed. St Patrick immediately had a church built, which he handed over to the Augustinian canons (who did not come to Ireland until the 12th century), locked the entrance to the pit and entrusted the key to the canons, so that no one would enter rashly without permission. Already during the lifetime of St Patrick a number of Irish entered the pit and were converted as a result of what they had seen. Thus the pit got the name of St Patrick’s Purgatory…

(from Pilgrimage in Ireland: the Monuments and the People by Peter Harbison, Barrie & Jenkins, 1991)

The entrance to this cave is on Station Island, and is the reason for the enduring popularity of the pilgrimage, which has persisted there for over 1500 years. In the medieval illustrations above, the gateway into Purgatory can be seen on the right, while on the left is a knight – Owein – whose terrifying adventures in the cave in medieval times have been written about in many languages: a summary can be found here.

St Patrick’s Purgatory: the name is over the entrance at the reception centre at Ballymacavany, the point of departure for Station Island. The cave which marks the entrance into Purgatory was permanently sealed up in October 1632 when the pilgrimage was suppressed by order of the Privy Council for Ireland; in the same year the Anglican Bishop of Clogher, James Spottiswoode, personally supervised the destruction of everything on the island. Later, in 1704, an Act of Parliament imposed a fine of 10 shillings or a public whipping …as a penalty for going to such places of pilgrimage… The site of the cave entrance lies under the bell tower, seen above. In front are the penitential beds where pilgrims perform rounds to this day. It is thought that these formations are the remains of monks’ cells or ‘beehive huts’.

On the left is a map of Station Island by Thomas Carve, dated 1666. The words Caverna Purgatory, centre left, show the site of the cave entrance. In spite of the efforts of the Penal Laws to suppress the observances, pilgrimages have continued unabated. Above right is a photograph from the Lawrence Collection, dated 1903, showing pilgrims about to embark for the island.

A young St Patrick portrayed as a pilgrim stands in front of the island: the Basilica is on the right. This view indicates the huge development of the island since its complete destruction in the 18th century and shows the facilities provided for the many thousands who have come here over the generations.

The Basilica is the focus of the pilgrimages today: it was formally consecrated in 1931. The entrance door is a modern interpretation of Romanesque architecture, while the tabernacle is an impressive example of fine bronze work.

Ireland’s great poets and writers have visited St Patrick’s Purgatory, and have responded to the experience:

Donnchadh Mór Ó Dálaigh (1244) “Chief in Ireland for poetry”:

Truagh mo thuras ar loch dearg

a Rí na gceall is na gclog

do chaoineadh do chneadh’s do

chréacht

‘s nach faghaim déar thar mo rosg.

(Sad is my pilgrimage to Lough Derg, O King of the cells and bells; I came to mourn your sufferings and wounds, but no tear will cross my eye)

Patrick Kavanagh:

Lough Derg, St. Patrick’s Purgatory in Donegal,

Christendom’s purge. Heretical

Around the edges: the centre’s hard

As the commonplace of a flamboyant bard.

The twentieth century blows across it now

But deeply it has kept an ancient vow.

W B Yeats:

Round Lough Derg’s holy island I went upon the stones,

I prayed at all the Stations upon my marrow-bones,

And there I found an old man beside me, nothing would he say

But fol de rol de rolly O.

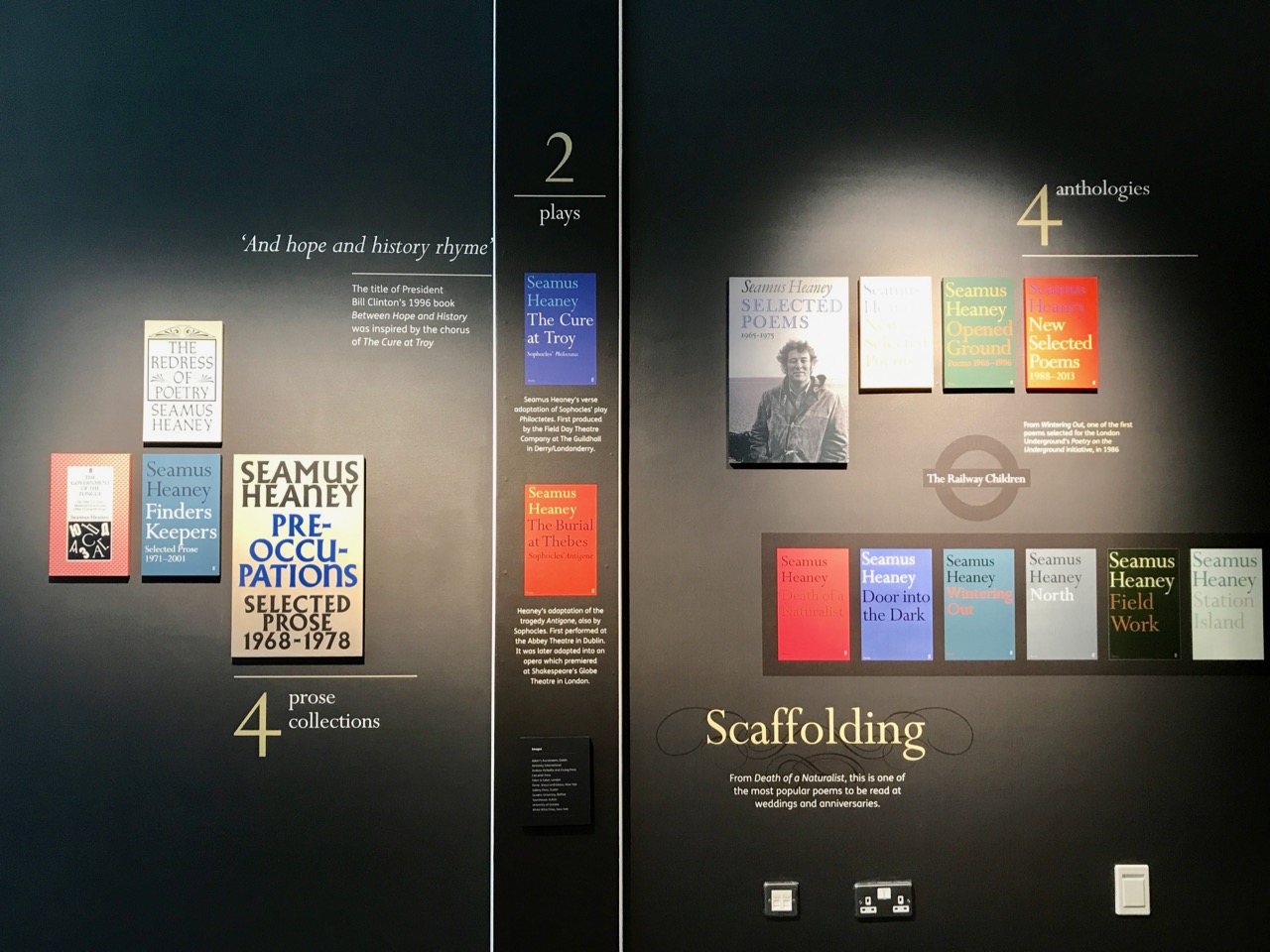

Most impressive of all, perhaps, is Seamus Heaney whose moving contemplations took him back through his life experiences and produced twelve memorable poems in a volume entitled Station Island:

How well I know that fountain, filling, running,

although it is the night.

That eternal fountain, hidden away,

I know its haven and its secrecy

although it is the night.

But not its source because it does not have one,

which is all sources’ source and origin

although it is the night.

I know no sounding-line can find its bottom,

nobody ford or plumb its deepest fathom

although it is the night.

And its current so in flood it overspills

to water hell and heaven all peoples

although it is the night.

And the current that is generated there,

as far as it wills to, it can flow that far

although it is the night.

Finally, here’s a contemporary journalist’s view, well worth the read!

Email link is under 'more' button.