I set out several weeks ago to write a single post about essays from Ireland of the Welcomes in 1972 devoted to our tradition of literature. There were six issues, therefore 6 essays – focusing on what Ireland had given to the literary world was one of the ways that the magazine ‘sold’ Ireland to its readers. I found myself so entranced with the first two topics – The Gaelic Story Teller and a translation by John Montague of a poem, Under Sorrow’s Sign, by the bard Gofraidh Ó Dálaigh – that each got a post of its own. And now I am down to the wire to do the four remaining essays in one post, before we more on to 1974 and I can stay 51 years behind, or maybe even catch up a bit. So here goes.

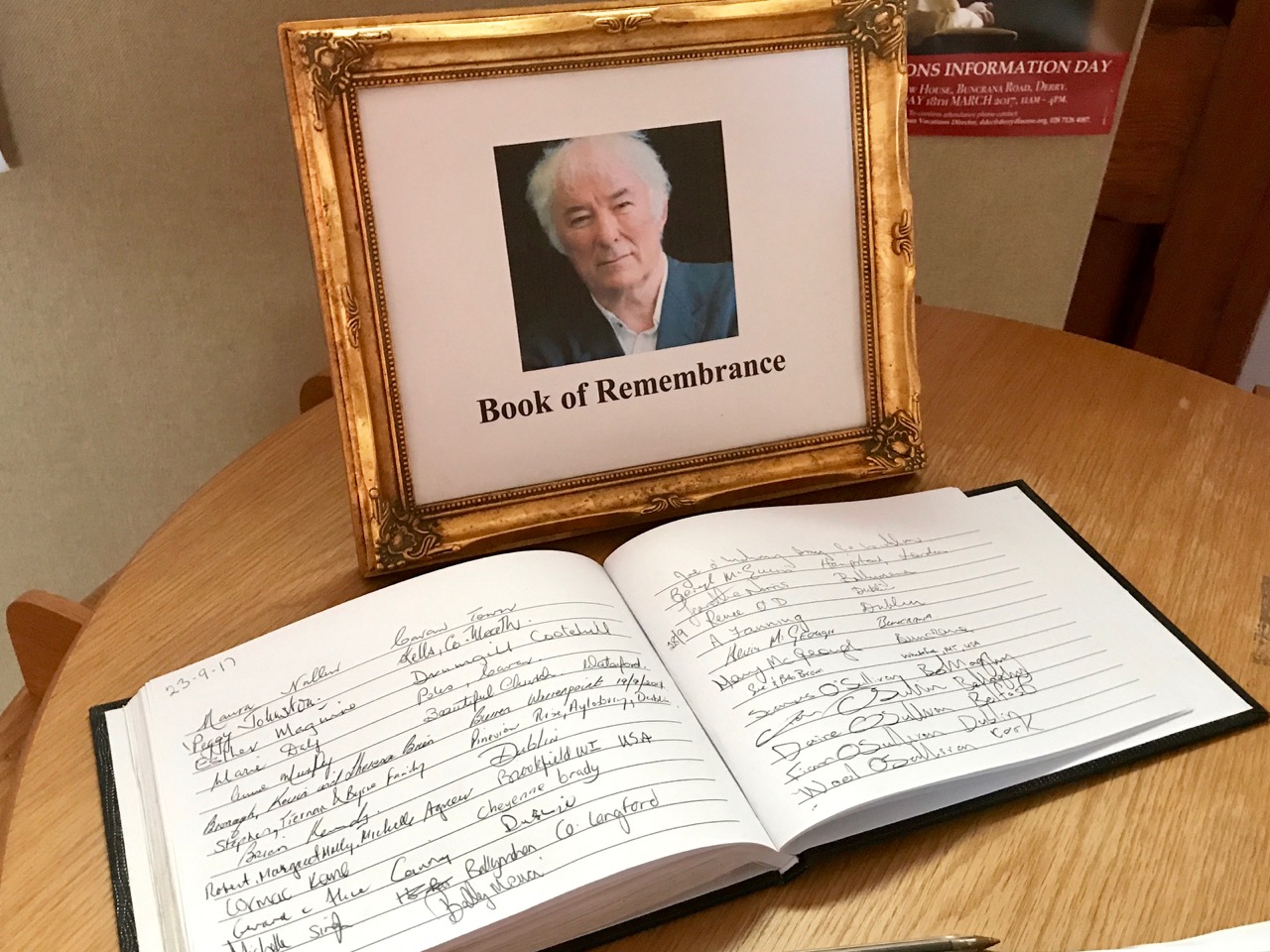

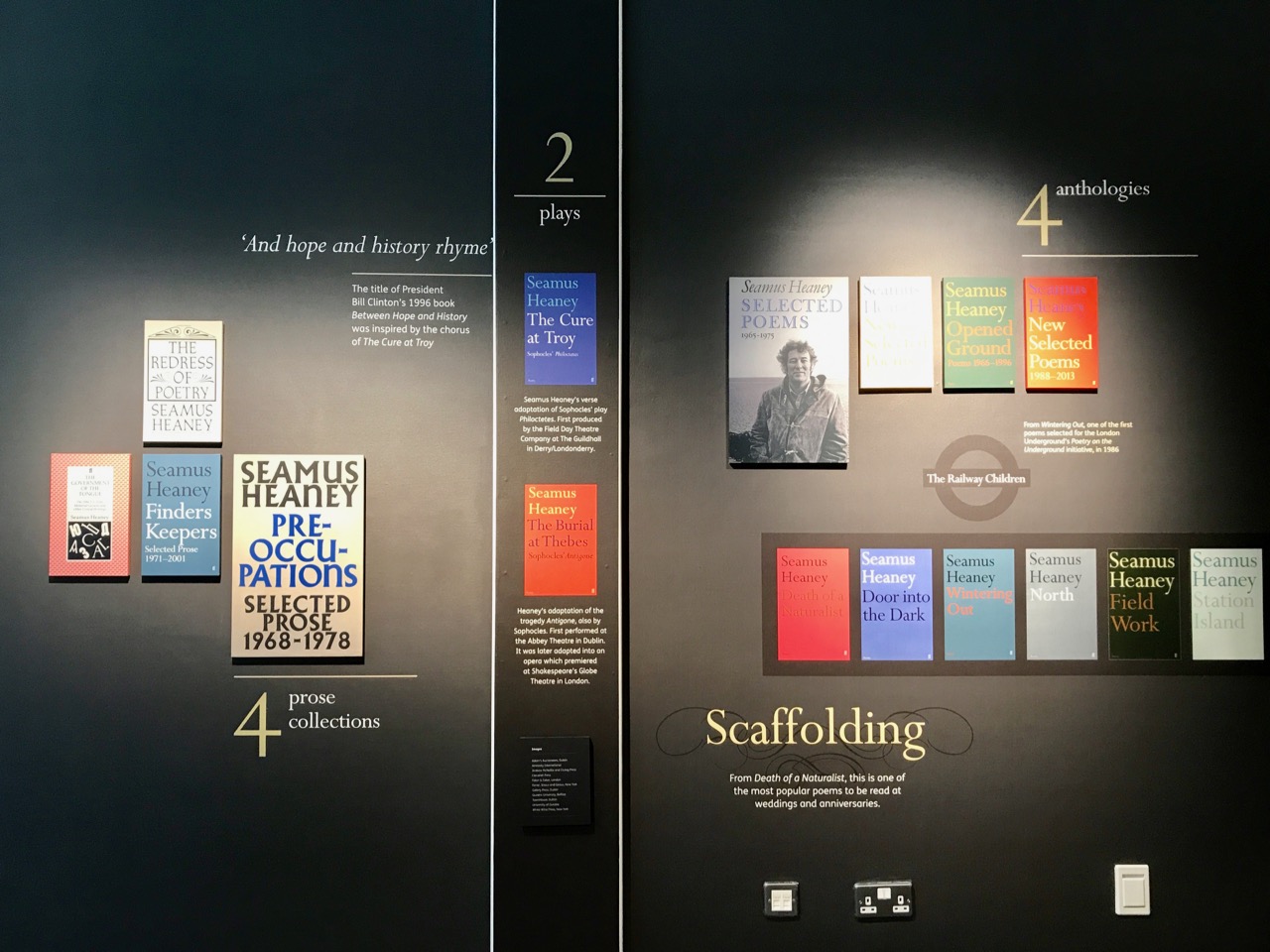

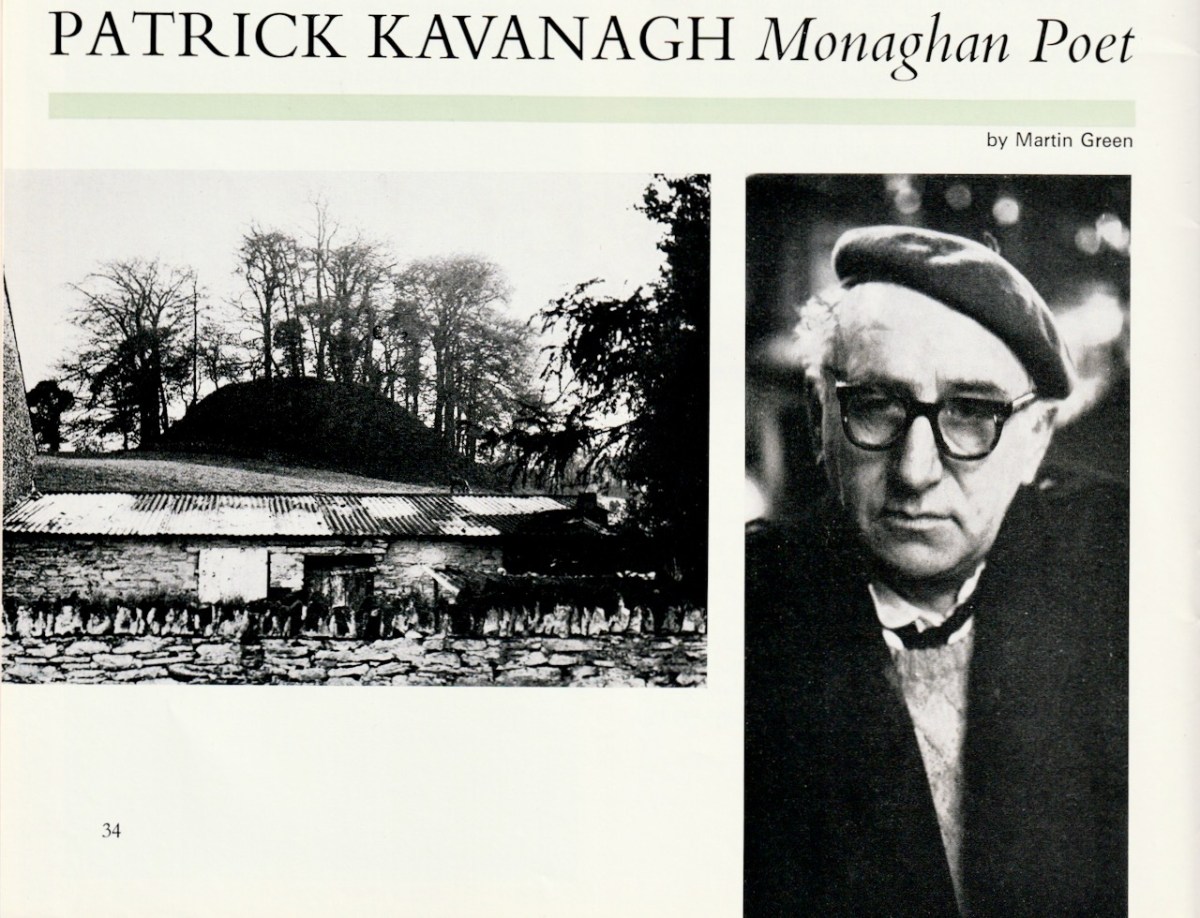

The January-February essay is by Martin Green and is titled Patrick Kavanagh, Monaghan Poet. Martin Green would make a column by himself – but I mustn’t get distracted. Here, he gives a brief description of Kavanagh’s life and considers how his rural Irish roots informed all his writings. He picks out Kavanagh’s autobiographical The Green Fool for special praise.

The Green Fool, in spite of the author’s later remarks that the book was ‘a stage-Irish life’, must surely be one of the gayest autobiographies ever written. There are no fearful soul searchings or tormented adolescent confessions, it is simply and purely a celebration of life, and way of life that was lived in rural Ireland in the early years of this century. And yet is is not dated, it is as fresh as today.

We have visited the Kavanagh Centre in Inniskeane – highly recommended.

I haven’t read The Green Fool – I wonder if that statement still holds up, 50 years later. Comments on a postcard, please. For a little more on Kavanagh, see Robert’s post On the Passing of Poets.

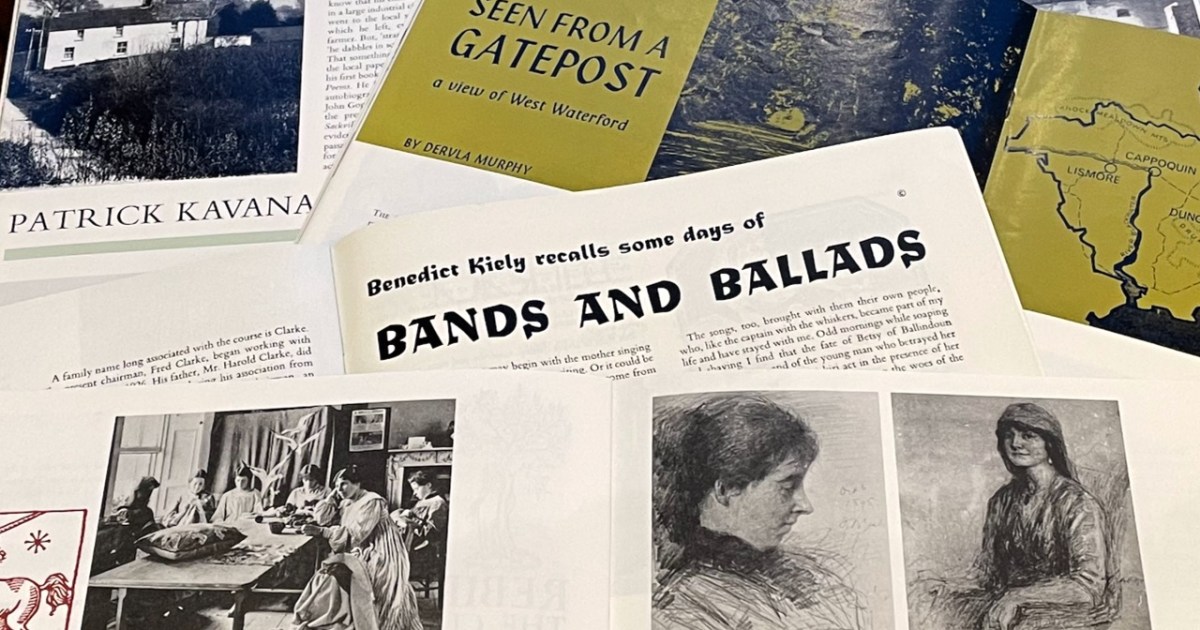

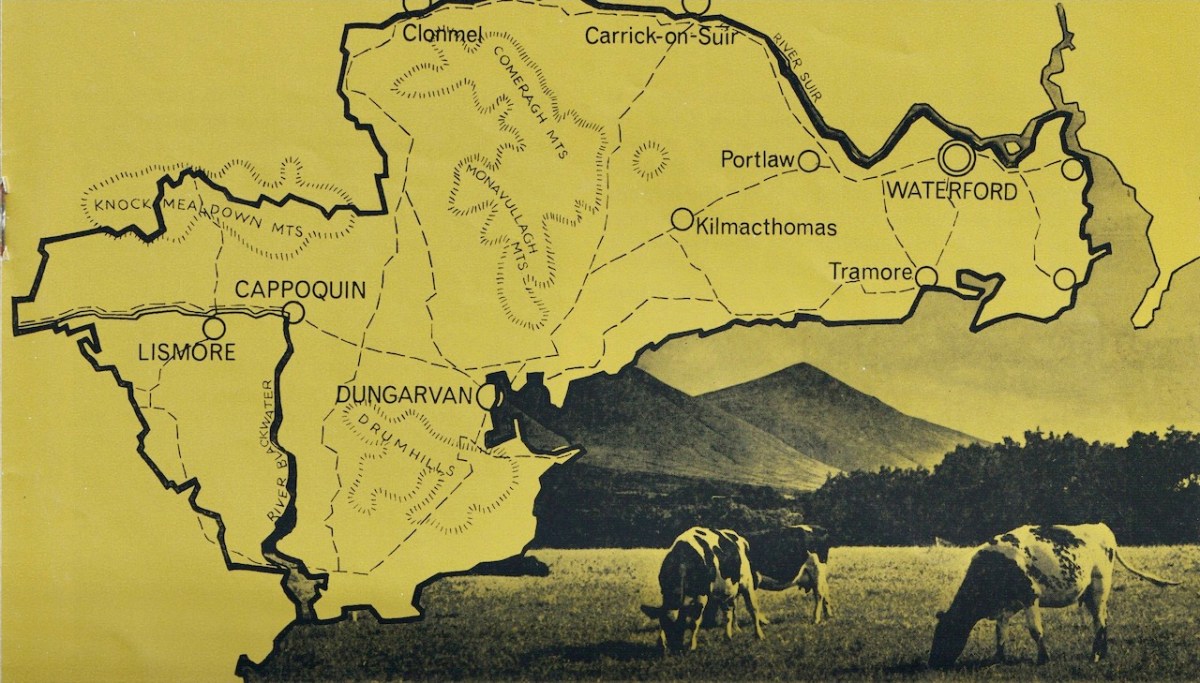

The second essay, from March-April, is by Dervla Murphy, much loved and missed Irish travel writer, who died last year at 90. Numerous obituaries will tell you more about Dervla, but perhaps my favourite is the one in the New York Times. All of them start with the gift from her parents at age 10 of an atlas and a bicycle, resulting in her plan to cycle until she got to India. Similarly, all of them speak of her love of Lismore and West Waterford, her home.

Dervla’s essay, Seen From a Gatepost: A View of West Waterford, is about this very place. In it you come to understand how, not unlike Kavanagh, her rootedness in an Irish rural landscape gave her that sense of security from which she could explore the world.

My third selection, from September-October, is a piece called Bands and Ballads by Benedict Kiely. From Co Tyrone, Kiely was one of the best known public intellectuals of my youth, frequently on radio and TV, or writing in the paper. Read his bio on the always-excellent Dictionary of Irish Biography site, written by Patrick Maume. This is a nostalgia piece for Kiely, here talking about his father:

The essay was originally written for the Irish Times. Unusually for Ireland of the Welcomes, it has a tiny © above the title, but no credit is given to the illustrator.

I have scanned the second page in full, as it is such a delight to read.

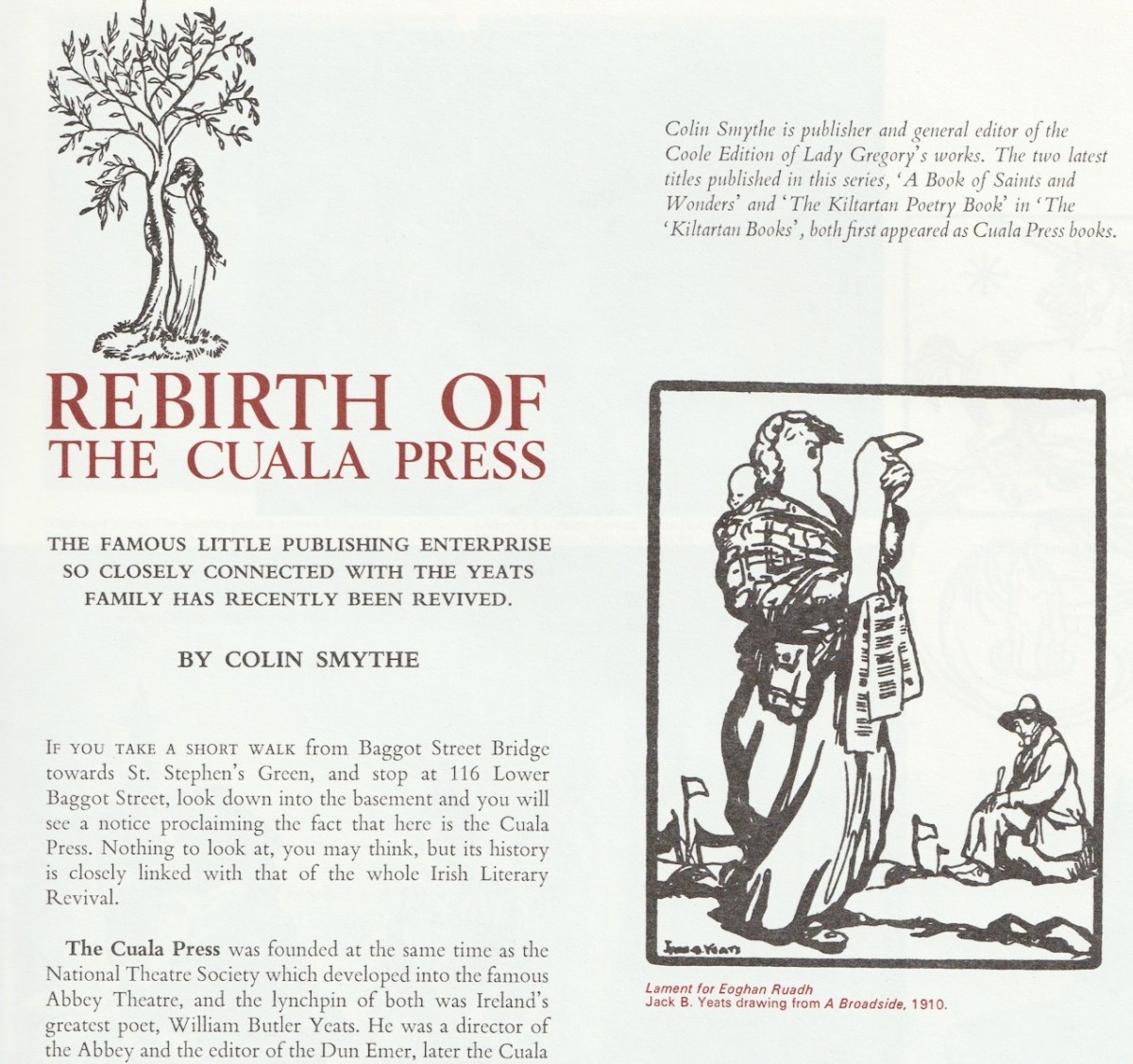

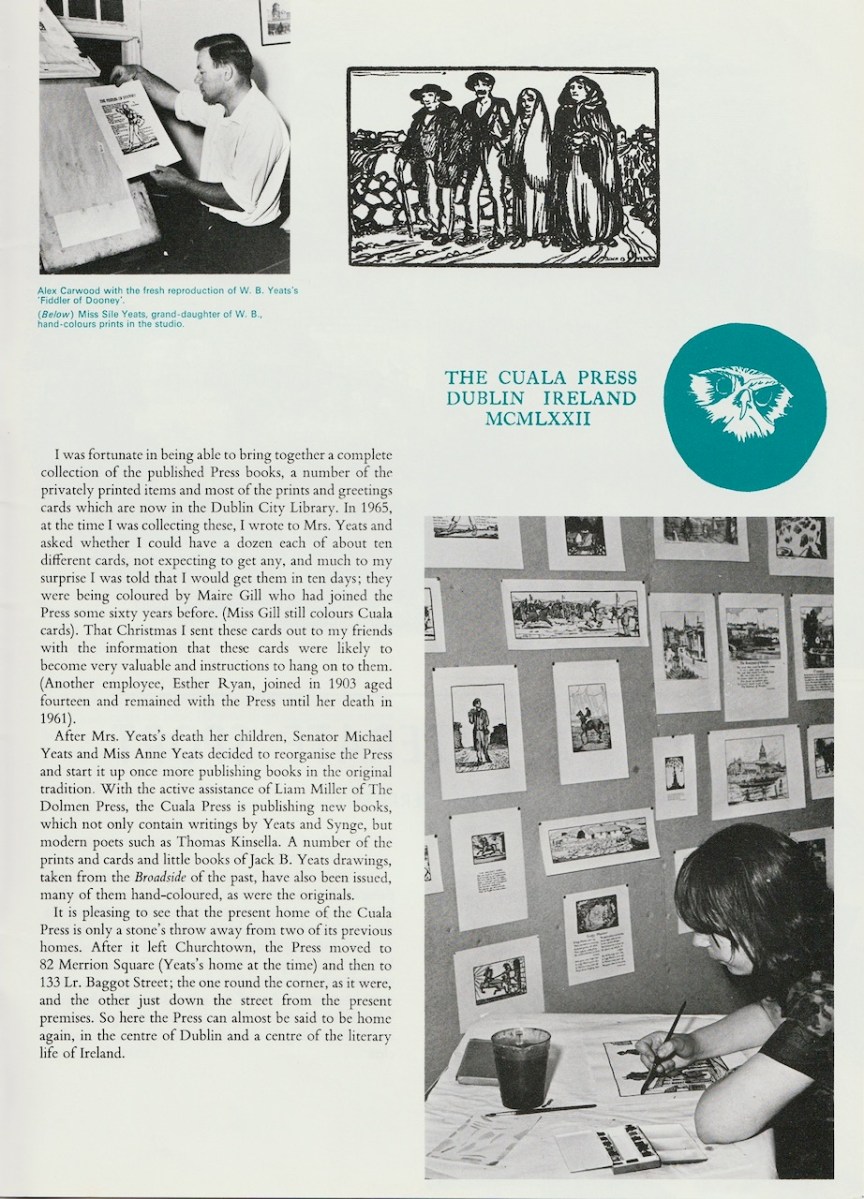

My final choice, from November-December, is by Colin Smythe and tells the story of the Rebirth of the Cuala Press. Managed by Elizabeth Corbet Yeats, the Press published its first book in 1903, and from then until 1946 it produced beautiful hand-coloured books of poetry of stories in limited editions – works of art in themselves. After that time it continued with cards and prints.

As the page below explains, it was revived by Michael and Anne Yeats, son and daughter of WB Yeats and Georgie Hyde-Lees, along with Liam Miller of the Dolmen Press.

Some of the archive has now been digitised by Trinity College Library and can be seen at The Cuala Press Collection. Here’s one of my favourites, in honour of the approaching Christmas season. It’s by Beatrice Elvery (©️ Estate of Beatrice Elvery Moss Campbell, Lady Glenavy.)

Whew – I made it. It was touch and go – any one of those topics is good for a full post. But I look forward to diving into the next whole year of Ireland of the Welcomes issues soon.