The term boulder burial was coined in the 1970s by Sean O’Nualláin, an archaeologist with the Ordnance Survey, to describe a class of monument that was quite prevalent in the south west, consisting of a single large boulder sitting on three or four support stones. The support stones lift the boulder off the ground and provide a small chamber-like area under the stone. Previously, this type of monument was known as a dolmen, a boulder dolmen or a cromlech, but O’Nualláin was convinced that the main purpose of these boulders was to mark a burial.

Illustrations from Jack Robert’s book Exploring West Cork

He based this belief partly on his extensive experience with other megalithic monuments, but also on the findings of the excavation of the Bohonagh complex, where Fahy found fragments of cremated bone in a pit under the boulder.

The Bohonagh complex includes a multiple-stone circle, a boulder burial and a cup-marked stone. A standing stone stood close by but has disappeared. Note the quartz support stone

However, William O’Brien excavated three boulder burials in the late 1980s and found no evidence of burials. In his book, Iverni, he comments in an understated way, “The absence of human remains at Cooradarrigan and Ballycommane does pose some questions as to their use.” His findings dated the sites to the Middle Bronze Age, between 3000 and 3,500 years ago.

A boulder burial from Lisheen Lower

What is unquestioned, though, is that they are predominantly found in the south west, especially in Cork, and that, while most occur alone, they are often found in groups, and/or in association with stone circles or standing stones.

This one is at Rathruane More, close to a significant rock art site and with views of Mount Gabriel and Mount Corrin

A boulder burial is a striking and unmistakable sight. Often situated on a high point or ridge it can be seen silhouetted against the sky – a large glacial erratic standing proud in the landscape. There are lots of examples around us here and most of them command extensive and often panoramic views. These are monuments that were built to be seen and to see from.

An exception to the high ground location is found at Dunmanus on the north side of the Mizen Peninsula. This boulder-burial is so low-lying, in fact, that one can only reach it at low tide

Ballycommane – the boulder is of white quartz

William O’Brien has pointed out that quartz is a feature of West Cork prehistoric sites and this is particularly evident in the case of boulder-burials. At Bohonagh, for example, some of the support stones are of gleaming white quartz, while at Ballycommane, Cooradarrigan and Cullomane the boulder itself is quartz. The sun was low in the sky when we visited Ballycommane and the sight of the quartz boulder gently gleaming was truly memorable.

The Mill Little complex

Boulder burials often occur in groups and in association with other monuments. Mill Little is a good example of this: three boulder burials are in a line with a standing stone pair at one end and a five-stone circle at the other. See our post Family-Friendly Archaeology Day for more photos of the Mill Little Complex.

This photograph shows the Cullomane boulder burial in the foreground, and a ‘penitential station’, in the background. This ‘station’ was part of a pilgrim round that involved prayer and penance – see Holy Wells of Cork for more detail on this site

At the Cullomane site, east of Bantry, the quartz boulder is surrounded by a variety of other monuments: a small stone circle, an ‘anomolous’ group of stone, a stone row, and standing stones all lie within a few fields of each other. Intriguingly, this site has seen continued ritual use through the millennia – there are also ring forts, burial grounds, a holy well and a ‘penitential station’ within the same small area.

The Ballycommane boulder is in close proximity to a standing stone pair

At Breeny More, near Kealkill, four boulder burials in a square pattern lie inside what remains of a large multiple-stone circle. This is an awe-inspiring site – you feel you are on top of the world with mountains all around and stunning views out to the end of the Beara and Sheep’s Head Peninsulas. See Robert’s post Walking the Past for a sense of what this site offers.

The Kenmare stone circle, above, has a boulder burial in the middle of it, while the Gorteanish stone circle on the Sheep’s Head, below, has at least one and possibly two boulder burials

So – if they weren’t tombs, or weren’t solely tombs – what was the purpose of these striking boulders? Their association with stone circles and rows provide evidence that they fit the calendrical pattern that we find in so many monuments of this era. Mike Wilson, the archeo-astronomer of the Mega-What site, has surveyed many of the West Cork boulder burials and has this to say: This survey shows that boulder-monuments were functional objects marking astronomically important places in the landscape. They cannot generally define an azimuth as accurately as a stone row or circle but capstone shape and orientation are usually significant, helping to indicate directions of interest.

At Breeny More the square layout of the four boulder burials within the stone circle provide many possible alignments

In several of the boulder burials we have observed, capstone shape and direction certainly seem to be a deliberate feature of the monument.

Robert checks the orientation of the long axis of the capstone at Rathruane More

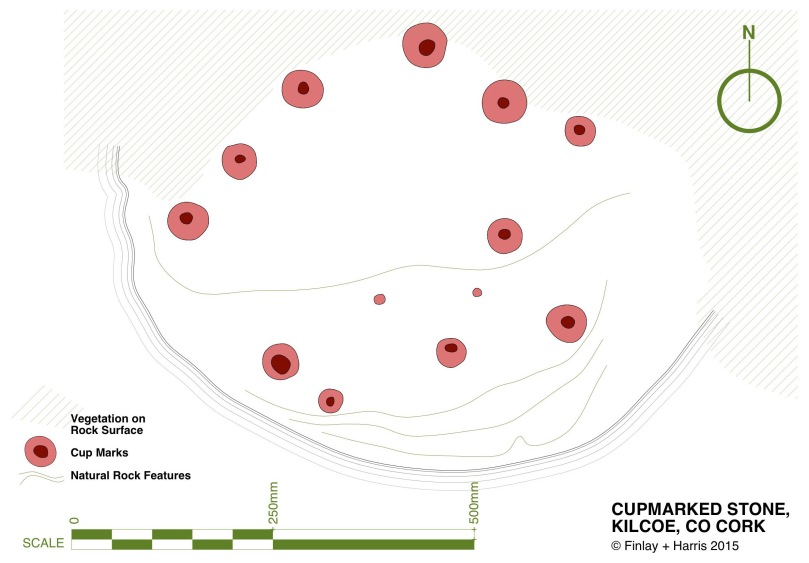

But perhaps the best example we have of how a boulder burial can have an orientation was drawn to our attention by local historian Brigid O’Brien – and she even sent us the evidence! If you stand at Bawngare, your attention is immediately drawn to the spectacular views to the west and north west – views that include Mount Gabriel, Mount Corrin and between them, faraway Hungry Hill on the Beara Peninsula, as well as the Sea in Roaringwater Bay. Interestingly, one of the support stones has several small shallow cupmarks (cupmarks are found on the capstones of several boulder burials).

The view west from Bawngare boulder burial

However the capstone with its distinctive long furrow holds the real secret, and Brigid’s persistence in braving the cold to visit at exactly the right time has unlocked that secret for us now.

From the other side the long furrow can be seen running the length of the capstone

Brigid visited it last year at the winter solstice and took this photograph of the setting sun. It seems the capstone was deliberately positioned to mark this alignment.

Brigid’s photograph, taken on December 21st, 2015

Perhaps it’s time to go back to calling them something other than burials – I rather fancy the old term boulder dolmens. What do you think?