Lissagriffin (the fort of Griffin) lies on the south-facing slope on the northern side of the salt marshes behind Barley Cove. It is a sunny spot with panoramic views back to the hills beyond Goleen and across the salt marshes below to the dunes of Barley Cove and the sea beyond.

The Barley Cove salt marshes – sit on the wall and just listen to the breeze in the reeds

Nowadays, it’s a peaceful place of farms and pasture land, but there are clues in the landscape and the old maps and records that there was much more going on here in times past.

The most visible reminder is the ruined church, surrounded by a graveyard. Once, these lands were in the possession of the Rev Fisher – remember him from my Saints and Soupers saga? They were associated with the Glebe Lands accruing to the Church of Ireland, which means that the rector was also the administrator of the graveyard, to whom you had to apply for permission for burial. The church and graveyard is known as Kilmoe (pronounced kill moo, meaning the the church of Muadh, although I haven’t been able to identify this saint), like the parish of the same name which occupies most of the Mizen west of Schull.

The graveyard has headstones going back to the 1700s, although I couldn’t find any from that era on my searches. All the local names are represented here, including the Burchills and the Wilkinsons of my Cousins Find Each Other post. It was in use as a burial plot during the Famine – a memorial plaque on the wall attests to this.

A feature of graveyards from this time was a watch-house, a reminder that bodysnatching was a lucrative trade. During the famine watch-houses also enabled people to be on the look out for dogs – there are accounts of dogs attempting to get at bodies barely covered by soil during this terrible time. There’s a ruined structure just inside the gate at Kilmoe (below), probably a watch-house from this time.

Like all historic graveyards around here there are many plots marked by simple stones, headstones and foot-stones, where people could not afford the services of an engraver. Remarkably, the knowledge of who is buried in some of those unmarked graves still resides somewhere, whether in church records or in the folk memory of local people. You can browse the listings of the graves here.

At the centre of the graveyard is a ruined church. It’s a very interesting structure to me, because I believe it is actually older than its normally-ascribed date. It was occupied, according to Brady’s Clerical and Parochial Records in 1581, when Dermot McCormack McCarthy was the rector and the church belonged to the College at Youghal and was dedicated to St Brendan. The Down Survey described it thus in 1700: Kilmoe : the church is ruinous, the walls that are standing are bad, built with stone and clay. The church stands about a mile from Crookhaven, to the westward near the head of Barlycove bay. 8A. of glebe on the north of the church; good land, set for £20 per an. There are the ruins of a vicaridge house joining to ye church-yard.”

There are hints in the structure of the Romanesque style, which would place it in the 12th century. The east window is clearly Romanesque in construction, while the door, with its plain lintel and ‘relieving arch’ also appears so.

I am seeking some confirmation of this and will update this post if or when I get a response. The west end appears to have been two storey – the joist supports are still projecting from the wall, which means that the old ground level was lower than it is today and that the window was in the second storey. That window (below) is ogee-headed – a clearly gothic element, which means (if I am right about the west end) that it was inserted later. The whole church may have been modified many times over the years it was in use.

There is a record of a cross-inscribed stone inside the church – we have looked for this but cannot find it. It may be gone, or it may be partially buried in the long grass. There’s no sign of the vicaridge house joining to ye church-yard.

The unusual ‘buttress’ feature on the north wall

But the landscape around has other elements too – or rather had other elements. There used to be an O’Mahony Castle just to the east of the church, of which no trace remains today. We know of it from Griffiths map of the 1840’s, (below: apologies for the blurriness, it seems to be the best resolution one can get) where it is clearly marked as a ruin. While many of the O’Mahony castles were closer to the shore, this one would have benefited from all-encompassing views of both land and sea, and from proximity to the church, for worship. According to James Healy’s The Castles of County Cork, it was probably tenanted by the O’Meighans, a bardic family associated with the O’Mahony clan. Although there is nothing left, local people told Healy in the 1980s that the site was cursed and that bad luck attached to it.

The view out to sea from the church

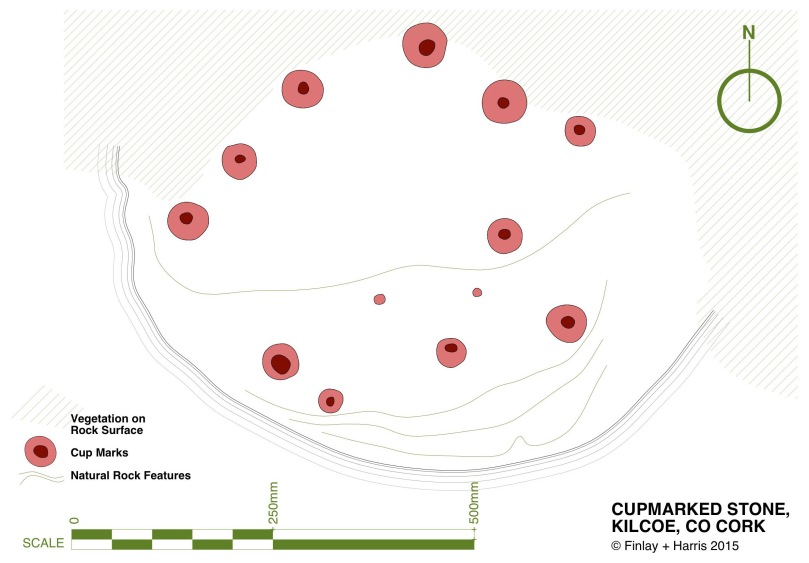

Even older still are the numerous standing stones that dot the hillside to the east and north. The photograph below shows one – a rather stumpy example. And probably even older than those are the cupmarks reported on the rock face just to the east of the graveyard. We have searched for these too, but were defeated by the gorse and brambles.

Of unknown vintage is the bullaun across from the graveyard gate. Although bullauns are often carved in free-standing boulders, this one was scooped out of the bedrock: it is known locally as a wart well. Dip your finger in, say the requisite prayers, and your wart will disappear. We even found a small bottle for Lourdes holy water left by it on one of our visits, showing that it is believed to still possess curative powers. Robert agrees! Amanda has included it in her Holy Wells blog.

Next time you’re headed out to Barley Cove on a fine day, take a little detour up to Lissagriffin church. The views alone are worth it, although a little wander around the graveyard will do a lot to soothe your soul.