Rathruane More: the view from the rock art site includes a knoll with a row of cupmarks on its upper surface, and Mount Gabriel on the horizon

QUESTION: Is there a real difference between rock art and cupmarked stones?

A joint post by Finola and Robert

Distribution of ‘rock art’ (left) and ‘cupmarked stones’ (right) in Ireland, according to the National Monuments classification scheme

In recording the rock art of County Cork so far we have concentrated mainly on those examples described in the National Monuments Records as rock art. In the course of planning the Cork survey, years ago, a decision was made to distinguish between rock art and cupmarked stones and so they are listed separately. However, other counties appear to lump them together, or use the generic term rock art to include stones bearing only cupmarks. In addition, some monuments are classified using their most distinctive feature: a wedge tomb or a standing stone, for example, may well bear cupmarks on a surface, but do not therefore show up as examples of either rock art or cupmarked stones on the records.

Drishane Cupmarked Stone. In other counties, this would be recorded as Rock art

This is how the National Monuments Website describes cupmarked stones: A stone or rock outcrop, found in isolation, bearing one or more small, roughly hemispherical depressions, generally created by chipping or pecking. There are a total of 99 examples listed in Ireland, of which 64 are in Cork. However, as we have seen above, this is an arbitrary and misleading classification and varies from county to county. The number of cupmarked stones that fit the NM description is likely to be much larger. The question is – should we preserve this distinction between stones labelled rock art and those labelled cupmarked stones? Is it useful or merely confusing?

Rathruane – included in the list of rock art because, besides numerous cupmarks, it also has cup-and-ring marks, a rosette, and lines. The first photograph in this post was taken from this surface

The cupmark is the most basic and numerous element or motif of rock art in Ireland and elsewhere. In the examples labelled rock art in County Cork, they occur with other motifs, principally concentric rings, sometimes with radial grooves, and a variety of curved or straight lines. They can be incorporated within a motif (as in cup-and-ring marks, rosettes, or where enclosed by lines) or they may be scattered, seemingly randomly, over the surface of the rock, between and among the other motifs.

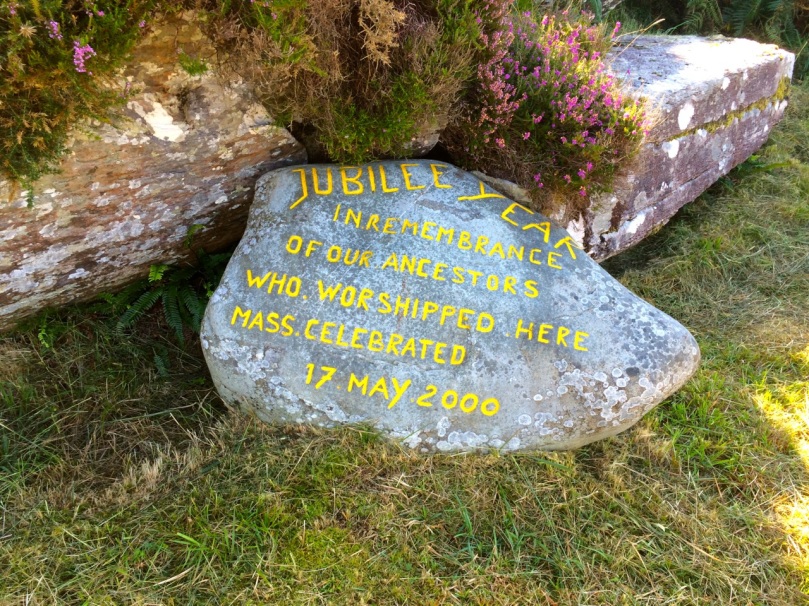

The two images above are from the shores of Lough Hyne. Two cupmarked stones lie on the beach, having probably fallen from the stone wall above. The right hand image is Robert’s drawing of the stone with 12 cupmarks

Since we have almost finished our recording of the rock art examples, we have moved on to focusing on those labelled cupmarked stones. As we spend time in the field recently with this class of monument we have begun to appreciate their differences from and similarities with rock art.

This simple cupmarked stone was placed many years ago within Knockdrum Fort, near Castletownshend, in the townland of Farrandau. It was brought to Vice-Admiral Boyle Sommerville by a local farmer

Let’s start with what differentiates them from rock art, apart from the obvious fact that the cupmark is the single motif employed in the carving.

- Where a stone is smaller and moveable, it is more likely to bear only cupmarks. This also makes them more vulnerable to loss and to incorporation into field walls and other structures. While there are examples elsewhere, here in Cork we have found no examples of cup-and-ring carvings on small, easily moveable, stones.

- We have found cupmarks on boulder burials here – Bohonagh is a good example, and Derreennatra (currently hidden under a mound of compost) may be another.

- In general standing stones, where they have carvings, are more likely to have only cupmarks (we have three exceptions to this in West Cork).

- The Bluid stone has cupmarks on both sides – there are no Cork examples with rock art on both sides.

The Bluid Stone is in Cork Public Museum but comes from near Castletownshend. It is a rare example of a stone with cupmarks on both sides, quite portable. Note the semi-circular patterns of the cupmarks

Bluid Side A

Bluid Side B

Now – what’s the same?

- Location: Most cupmark-only carvings are found in the open countryside, on large earthfast boulders or rock outcrops.

- Clusters: as with rock art, cupmarked stones are often found within a kilometre or two of other examples or are within sight of each other or within site of rock art (intervisibility).

- Carving technique: where it can be discerned, it appears to be the same as for rock art – pecking with a harder stone. In the case of some of the shaley sandstone that laminates easily, it is impossible to tell how the cupmarked was formed – it may have been simply bashed out.

- Siting: where the cupmarks are found in situ, their siting is equally spectacular to rock art. In particular, many of them are found on rising ground with strongly marked horizons that include views, even quite distant views, of Mount Gabriel, Mount Kidd, or other prominent horizon features. The sea, or water in the form of a lake, stream or river, is often a feature of the vista from the rock. We have not worked with enough of them yet to form any opinion on whether they are sited at what may have been routes through a landscape or territorial boundaries.

- Patterns: as with more complex rock art, often the cupmarks appear to be scattered randomly over the surface of the rock. However, patterns of straight lines, or of rough circles or semi-circles, can be made out in several of the stones we have recorded to date.

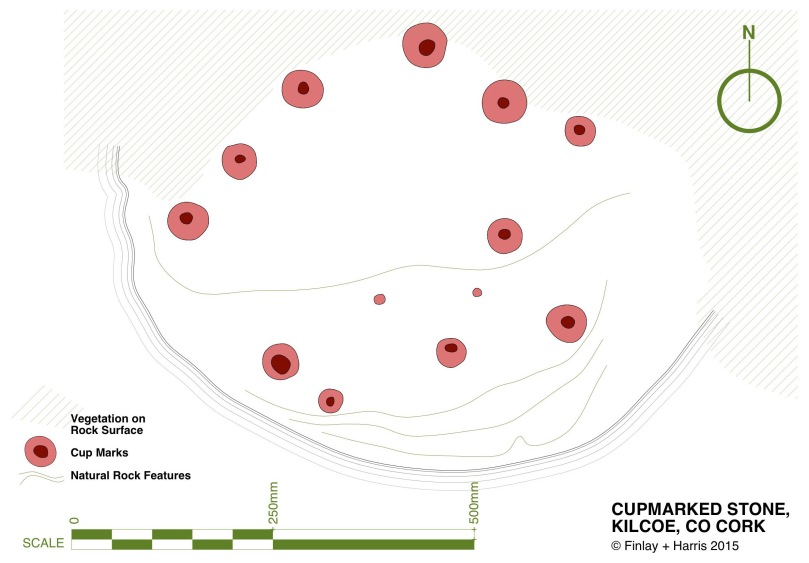

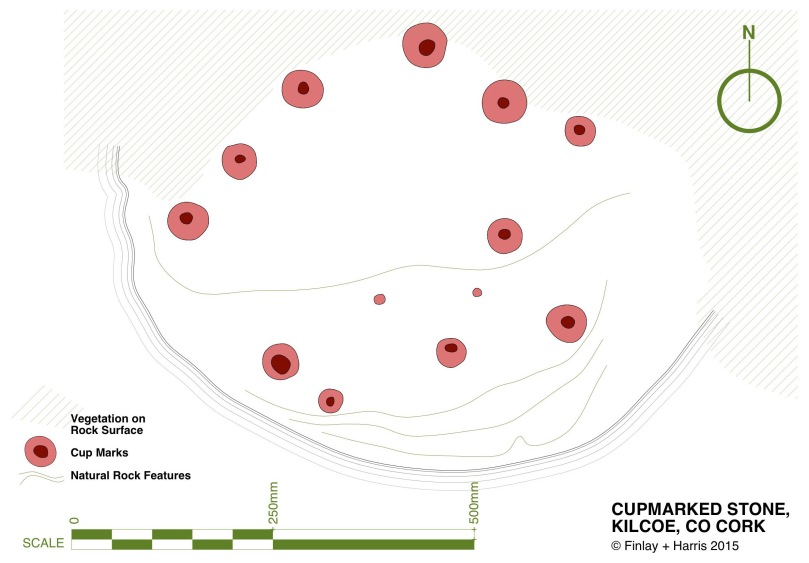

Robert points to two outcrops in Kilcoe. The lower one has one cupmark, the upper one has 13 cupmarks arranged in a rough circular patter. The sea and Mount Gabriel are visible from this location, as well as some rock art

In researching this piece we have been influenced by Christiaan Corlett’s book Inscribed Landscape: The Rock Art of South Leinster. Christiaan is an archaeologist with the Dept of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht and specialises in the archaeology of Leinster, and especially Wicklow. His book has been the first to catalogue the extensive body of rock art in the South Leinster area (indeed the first published work on rock art in Ireland) and in his corpus he includes both cup-and-ring art and cupmark-only stones without undue distinction. He notes many of the same things about rock art that we have observed. For example, he was struck, as we were, by the dominance of high mountains (in his case, Mount Leinster, the Blackstairs, or Brandon Hill) in the horizon views from the rocks he studied, and by the intervisibility of stones from each other.

The newly-discovered Kilbronoge cupmarked stone. From it you can see Roaringwater Bay and a wedge tomb to the SE, and Mount Gabriel diametrically opposite in the NW

Robert’s drawing of the Kilbronoge Cupmarked Stone, made using architectural survey and CAD techniques

His work is a strong argument for the inclusion of all cupmarked-based prehistoric carving under one rubric – rock art. First of all, he argues that it is all likely to be of a similar early origin. Recent thinking is that rock art may predate megalithic art and belong to the Early Neolithic (at least 5,000 years old). In fact, the cup-and-ring art may already have been dying out during the great flowering of megalithic art that we see at Newgrange, Knowth and Loughcrew. Cupmarks on their own may have persisted longer, as they are found in association with Bronze Age monuments such as wedge tombs and boulder burials. Here’s what he has to say about our search for meaning, vis-a-vis the humble cupmarked stone (p.78):

Arguably, it is only within the context of the overall composition that we may come close to some comprehension of the motifs found in rock art. Even the meaning of a completed composition, however, may only have been understood by the person(s) responsible for it. Perhaps the symbols represent a complex message of family history or a personal spiritual journey associated with an initiation ceremony or rite of passage, or perhaps they simply served to delineate family, tribal or sacred boundaries… [There is] a natural temptation to focus on the more elaborate designs and compositions found in rock art, as if they are more important because they are more accomplished. Yet the frequency of compositions consisting solely of plain and unelaborated cup-marks should not devalue their significance. Clearly their commonness would strongly suggest that these examples were just as important as, or maybe even more important than, the most elaborate examples of rock art found in the region. Given the intrinsic simplicity of a composition consisting entirely of cup-marks, however, it is arguably impossible to decipher or decode the specific meaning of the symbols themselves. That is not to say, of course, that we cannot attempt to understand the broader message of rock art, particularly where a complex of sites can be analysed. In such cases it may be the context of these sites that will provide the key to unlocking the meaning of rock art, in terms of the position and relationships within a given landscape, and the relationship with other examples of rock art on the vicinity.

The Kilcoe Cupmarked stone. The original record described three cupmarks – in fact there are 13, arranged in a rough circle

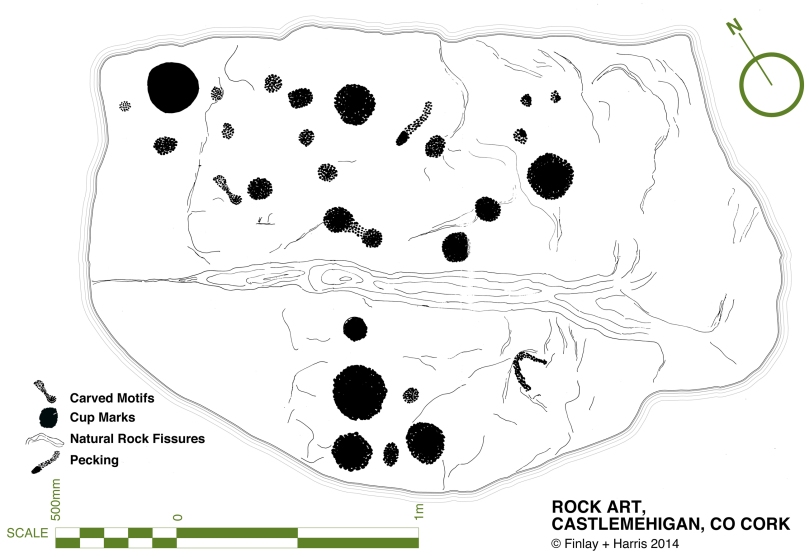

Christiaan deals with the similarity of cupmarks to the bowl-shaped depressions known as bullauns, assumed to be Early Medieval. But that’s a topic for another day. Suffice it to say here that one of our favourite stones, Castlemehigan, may have both cupmarks and bullauns on its surface, as well as a cross indicating its later use as a mass rock. In its extraordinary mix of seemingly-randomly-scattered but also possibly-linear-arrangement of cupmarks; large bowl and basin-shaped elements; a spectacular siting that includes views to a distant Mount Gabriel and a closer view of the sea; a nearby cluster of other cupmarked stones; and the folklore that surrounds it – this very special cupmarked stone embodies all that is wonderful about this class of ancient monument.

Castlemehigan cupmarked stone

To come back to the question we posed at the beginning – should we preserve or abandon the notion that we are dealing with two classes of monument – rock art versus cupmarked stones? Our answer is that we’re not sure. What do YOU think?

The Giant’s Grave, Drishane. It bears numerous cupmarks on the upper surface of the ‘capstone’

For those interested in more of our posts on rock art, go to Derrynablaha Expedition and scroll to the end for a list.

Email link is under 'more' button.