This post was originally published way back in 2014 but I have updated it with a few new photographs and edited the text slightly.

An raibh tú ag an gCarraig? / Were You at the Rock?

nó a’ bhfaca tú féin mó grá / Or did you yourself see my love,

nó a’ bhfaca tú gile, / Or did you see a brightness,

finne agus scéimh na mná? / The fairness and the beauty of the woman?

This beautiful song speaks to a revered tradition in Irish history and folk custom – the mass rock. During the period of the Penal Laws (late 17th and first half of 18th Century) when the practice of Catholicism was outlawed, parishioners would gather at a secret location to attend mass. The priest travelled from community to community in disguise, a lookout was posted, and mass was celebrated on a lonely rock far from the reach of the law. The song encodes the message that the people still find ways to attend mass, despite the harsh prohibition against it.

Mass rocks are often in remote locations, such as this one in Kerry, or the lead image on the Beara

Dr. Hilary Bishop, in her excellent website Find a Mass Rock says, As locations of a distinctively Catholic faith, Mass Rocks are important religious and historical monuments that provide a tangible and experiential link to Irish heritage and tradition. She also points out that, because of the imperative for secrecy, mass rocks are difficult to find.

This stained glass window shows mass at a mass rock, with a lookout posted to keep an eye out for the redcoats

We certainly experienced this when we set out for a day of mass rock hunting. Working from a list generated from the National Monuments Service database we spent a day on the Sheep’s Head and the Mizen and had trouble finding all the rocks on the list. One, if it was still there, had disappeared under impenetrable layers of gorse. A second rock was last recorded in the 1980s: residents were no longer familiar with it.

One of our favourite holy wells, at Beach on the Sheep’s Head, also incorporates a mass rock. Mass is celebrated here every August

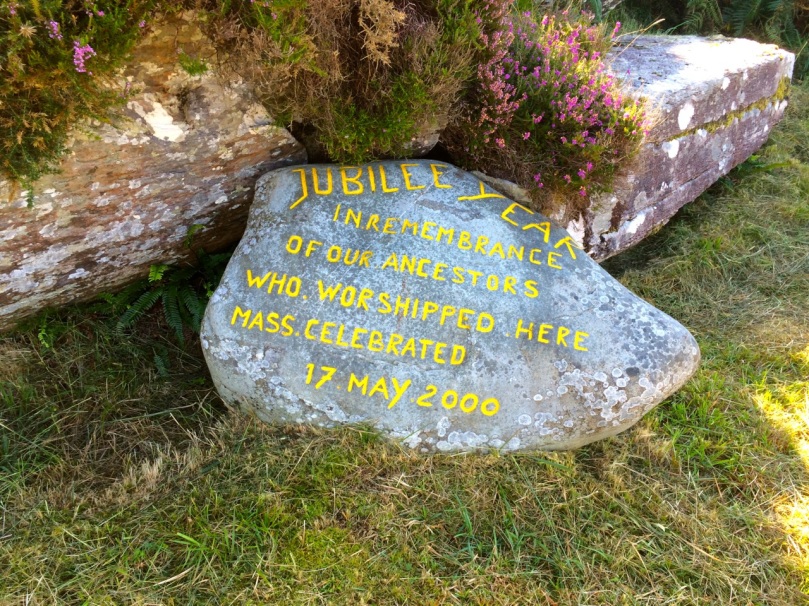

Knowledge of mass rocks has passed down from generation to generation. In the deep countryside, the sites maintain a mystique and a sense of the sacred. We’ve written about the mass rock and holy well at Beach, where Mary conjured up a blanket of fog to confuse the English soldiers and allow the priest to escape. At Beach and at our first stop, the mass rock at Glanalin on the Sheep’s Head Way, mass is still celebrated.

The Glanalin rock (above), and the one we visited on the Beara Peninsula, are good examples of the remote locations typical of many mass rocks, high on a hillside or hidden in an isolated valley. You can picture the procession of worshippers, in ones and twos, slipping silently through the bracken, pausing to make sure they are not being watched, climbing higher, following an overgrown trail, arriving at the meeting place where the hushed crowd awaits the arrival of the priest.

One of the rocks we found (above) looked for all the world like a fallen standing stone – and that’s probably what it was. (I wonder if I should go to confession, though – I’m sure that sitting on a mass rock would qualify as at least a venial sin.)

A mass rock that is easily visited is the one at Cononagh Village (above), right at the side of the main road into West Cork, the N71. This site is beautifully maintained – Cononagh is obviously proud of its heritage: signage and flowers invite the passerby to take a closer look.

The mass rock we visited last year, at Foherlagh, has a commanding view of the surrounding countryside. This one even had a small scoop-out in the rock, identified as a holy well

Another easily accessible site is Altar, at Toormore. This is a wedge tomb, probably over 4,000 years old and excavated in 1989. It remained in use through the Bronze Age and into the Iron Age. Dr. William O’Brien, in Iverni, says of this site: …over time this tomb came to be regarded as a sacred place, housing important ancestral remains in what was a type of community shrine. How fitting, then, that the flat capstone of the Altar wedge tomb became, in the Penal Days, a mass rock. And how intriguing to think of the continuation of this sacred space over the course of thousands of years.

But perhaps our favourite of all the mass rocks we have visited is the one at Castlemehigan. We wrote about it here. It started out life as a cupmarked stone perhaps in the Neolithic, then probably got converted into a bullaun stone in the Early Medieval period, before finally serving as a mass rock – and it has all the stories to go with its long history.