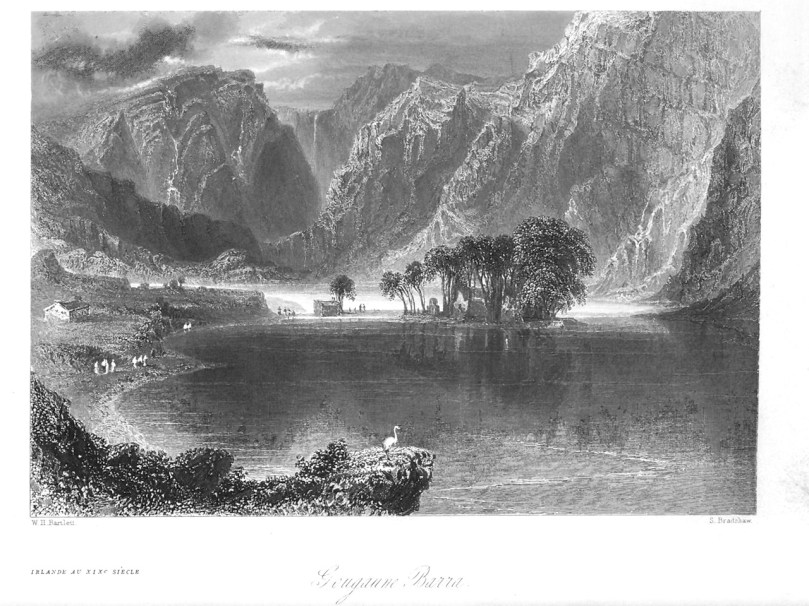

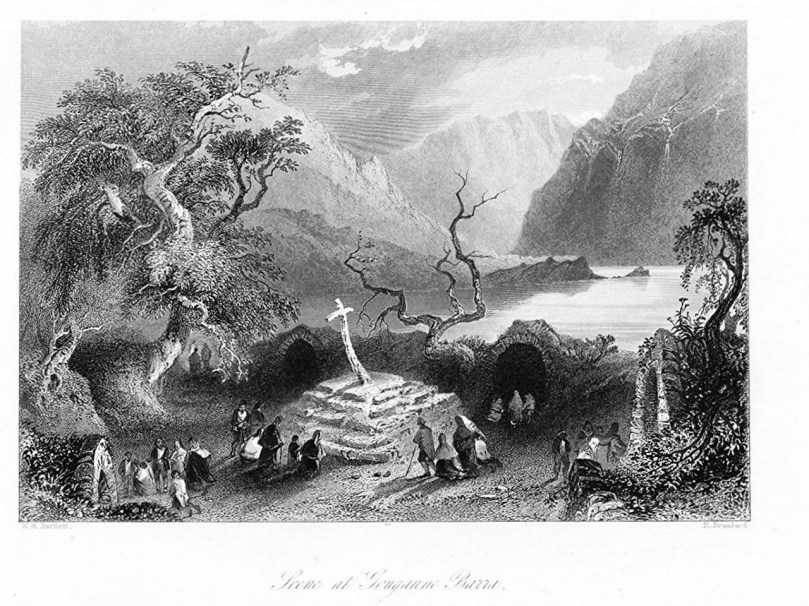

William Henry Bartlett was one of the foremost illustrators of his day, specialising in exotic scenes from all over the world – including Ireland, a favourite destination for Victorian travellers. I gave you an introduction to Bartlett in Scenery and Antiquities – W H Bartlett in Nineteenth Century Ireland. He loved ruins and wild and romantic scenery and wasn’t above enhancing its grandeur and magnificence. What better place for him to come than Gougane Barra? He was there sometime between 1830 and 1840 and he left us two engravings of what he saw – incredibly valuable as evidence of what has changed and what has not.

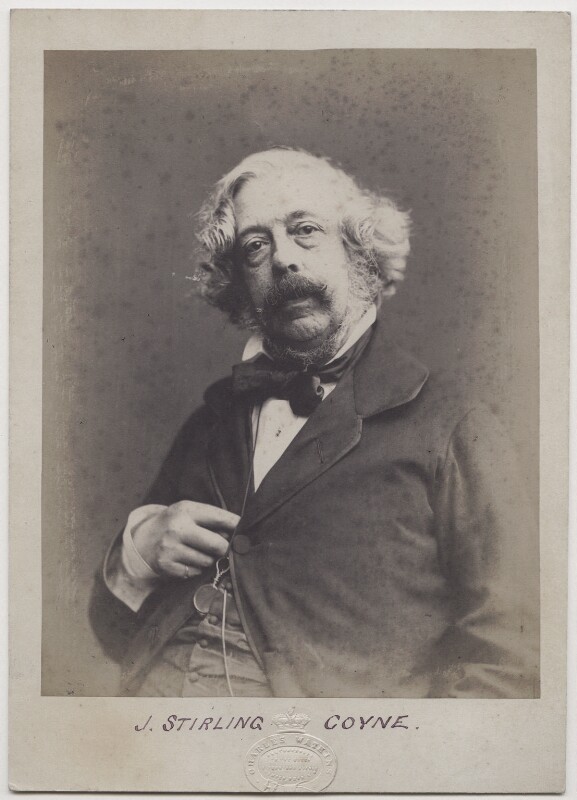

Joseph Stirling Coyne by Octavius Charles Watkins, salt print, late 1850s, © National Portrait Gallery, London, used under license

The writer of this volume of Scenery and Antiquities of Ireland was an Irishman – Joseph Stirling Coyne, born in Birr in 1803. Although he studied for the law, he had such success with his first couple of plays that writing become his full time profession and he eventually moved to London and wrote a string of hit comedies for the stage. He was one of the founders of Punch and contributed many pieces to newspapers and magazines, but Scenery and Antiquities seems to have been his only book. His ear for dialogue, it was said, was particularly good – but you can decide that for yourself as you read the story he tells about St Finbarr and the Serpent (see another version here).

The wild and romantic country around Gougane Barra

Coyne certainly knew how to match Bartlett’s penchant for overblown romanticism with his own hyperbolic language. Why don’t we leave the two of them at it now? Bartlett’s engravings and Coyne’s descriptions (edited for brevity) will carry us through Gougane Barra as it was in the 1830s. I will intersperse a few of my own images to provide some modern contrast and a certain reality check on the ‘precipitous crags’ and the ‘wild and beautiful solitudes.’

Detail from Bartlett’s view of Gougane Barra – he used scale to emphasise the towering nature of the cliffs above Gougane Barra Lake in the romantic style of the period

From Scenery and Antiquities of Ireland, published in 1841

Leaving Inchageela I found myself entering into the deep solitude of the mountain district, where the Lee expands itself into a beautiful sheet of water called Lough Allua (from Lough-a-Laoi, the Lake of the Lee,) about three miles in length, and in some places nearly a mile in breadth. This lake is picturesquely dotted with clusters of islands; but the natural beauty of the scene has been considerably impaired by the destruction of the woods which clothed the islets, and skirted the shores of the lough. The road which has been recently constructed lies on the northern side of the lake, following the indentations of its winding shores, through scenery of the most diversified yet solitary character, which will gratify the warmest expectations of the tourist who has leisure to investigate all its various beauties. After passing the lake, the river contracts itself into a narrow stream, and the traveller approaches, through narrow defiles and deep glens, the sequestered lake of Gougaune Barra, the first pausing place of the infant Lee, which bursts from the deep recesses of a rocky mountain a short distance from this spot.

I’ve done the same thing – foreshortened the view in order to dwarf the oratory under the ‘towering’ cliffs

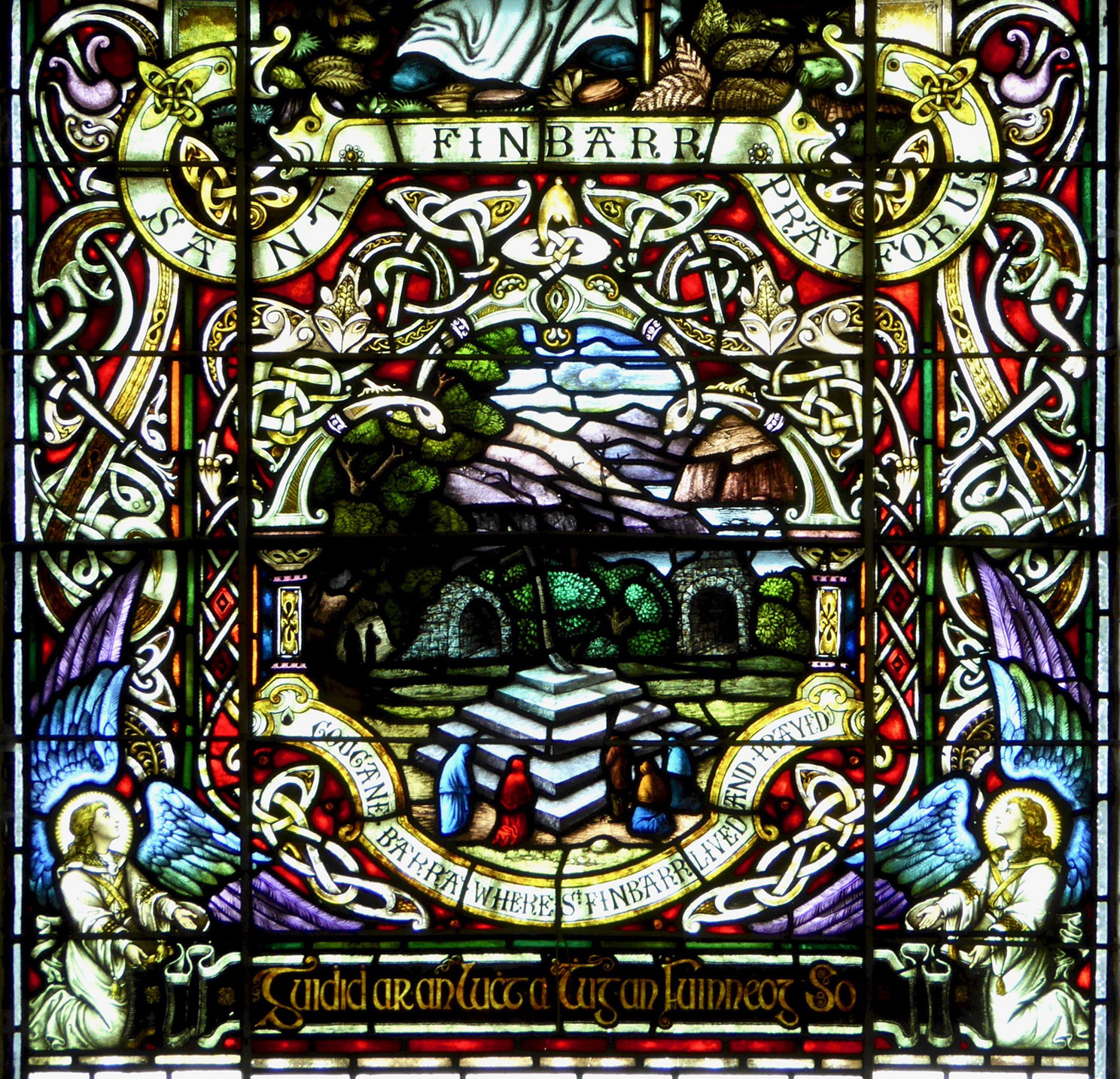

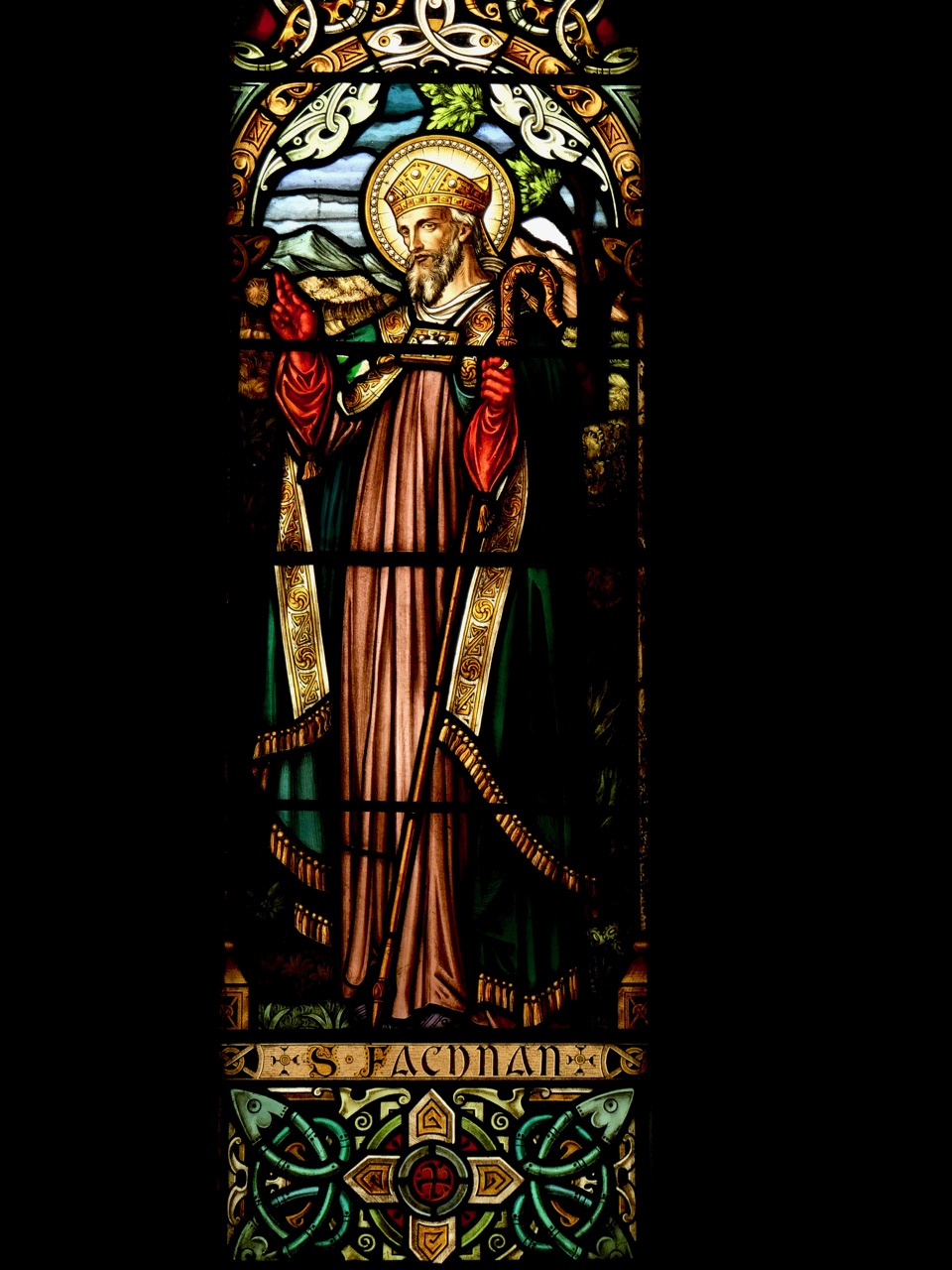

Antiquarians have assigned different etymologies to the name of this lake; some translate it, the Hermitage or Trifle of St. Barr or St. Barry. Mr. Windele, who is generally accurate in his derivations, says, that Gougaune is taken from the Irish words Geig-abhan, i. e. the gorge of the river. How he could have fallen into such an error is surprising, when it is evident that the name is derived from the artificial causeway, which connects with the shore a small island in the centre of the lake, where St. Fineen Barr lived a recluse life before he founded the Cathedral of Cork. The word gougaune is applied in the south-western districts of Ireland to those rude quays of loose stones jutting into the sea or river, constructed for the purpose of fishing. The lake, which is situated in a deep mountain recess, is enclosed on every side except the east with steep and rocky hills, down whose precipitous sides several mountain-streams pour their bright tributes into the placid waters beneath.

A beautiful scene but a more realistic view of the height of the mountains at the end of the lake

The sanctified character of Gougaune Barra has, according to popular tradition, preserved it from that legendary monster, which, under the form of an enormous eel, infests many of the lakes in Ireland. One of these enchanted worms had in past ages taken up his quarters in this lough, where he remained unmolested until, by an act of daring sacrilege, he provoked the anger of St. Fineen Barr, and caused his own expulsion from the pleasant waters he had so long inhabited. The story was told to me by an old man whom I found fishing in the river, where it issues from the lake; and, as I should only detract from the simplicity of his legend by giving it in other language than his own, I shall, as nearly as possible, repeat it in the manner in which it was told to me.

Richard King’s St Finbarr and the Serpent published in ‘The Capuchin Annual’ (1946-7), used with thanks

”There was wanst upon a time, sir,” said he, “a great saint, called Saint Fineen Barry, who lived all alone on the little island in the lake. There he built an illigant chapel with his own hands, and spent all his time in it day and night, praying, and fasting, and reading his blessed books. So, sir, av coorse, his fame went about far and near, and the people came flocking to the lake from all parts ; but as there was no ways of getting into the island from the shore—barrin’ by an ould boat that hadn’t a sound plank in her carcash—there was a good chance that some of the crathers would be drownded in crassing over. So, bedad, St. Fineen seeing how eager the poor christhens wor for his holy advice, tuck pity upon them, and one fine morning early he gets up, and, afore his breakfast, he made that pathway of big stones over from the land to his own island. After that, the heaps of people that kem to hear mass in his chapel every Sunday was past counting; and small wondher it was, for he was the rale patthern of a saint, and mighty ready he was at all sorts of prayers that ever wor invinted. But I forgot to tell you, sir, that there was living at that time, snug and comfortable, down in the bottom of the lake a tundhering big eel; some said he was a fairy, more that he was a wicked ould inchanther, that the blessed St. Patrick had turned into that shape. Any way, he used to divart himself now and then with a walk upon the green shores of the lake, and those that saw him at these times said, that he had the ears and mane of a horse, and was thicker in the waist than a herring-cask. But with all that, the crather never milisted nobody, till one fine Sunday, after St. Fineen had finished saying mass in his little chapel, and was scatthering the holy water over his congregation, all of a suddent the ould eel popped up out of the lake, and, thrusting his long neck and head into the chapel window, caught hoult of the silver holy wather-cup betune his teeth, and without so much as ‘ by your lave,’ walks off with it into the wather. Of course, there was a terrible pillalieu riz in the chapel when they seen what the blaggard eel was afther doing, and in half a minute every mother’s son had run down to the wather-side pelting him all round the lake. But the plundhering ould rogue only laughed at their endeavours, till St. Fineen himself kem out of the chapel, drest in all his vistmints, ringing the mass-bell as hard as he could. Well, no sooner did the eel hear the first tinkle of the blessed bell than away he swum for the bare life out of the lake into the river, purshued by St. Fineen, till he got to the fall of Loneen, when he dropped the cup out of his mouth. The saint however hadn’t done with him yet, for he kept purshuing him to Lough Allua, where he thought to hide; but the sound of the bell soon forced him to leave that, and swim down the Lee to Rellig Barra, and there St. Fineen killed the oudacious baste with one kick of his blessed fut, and afterwards built a church on the spot; which, as your honour may perhaps have heard tell, is now the cathedral of Cork. At any rate, sir, there has never been another of them big eels seen in the lake from that time to the present.”

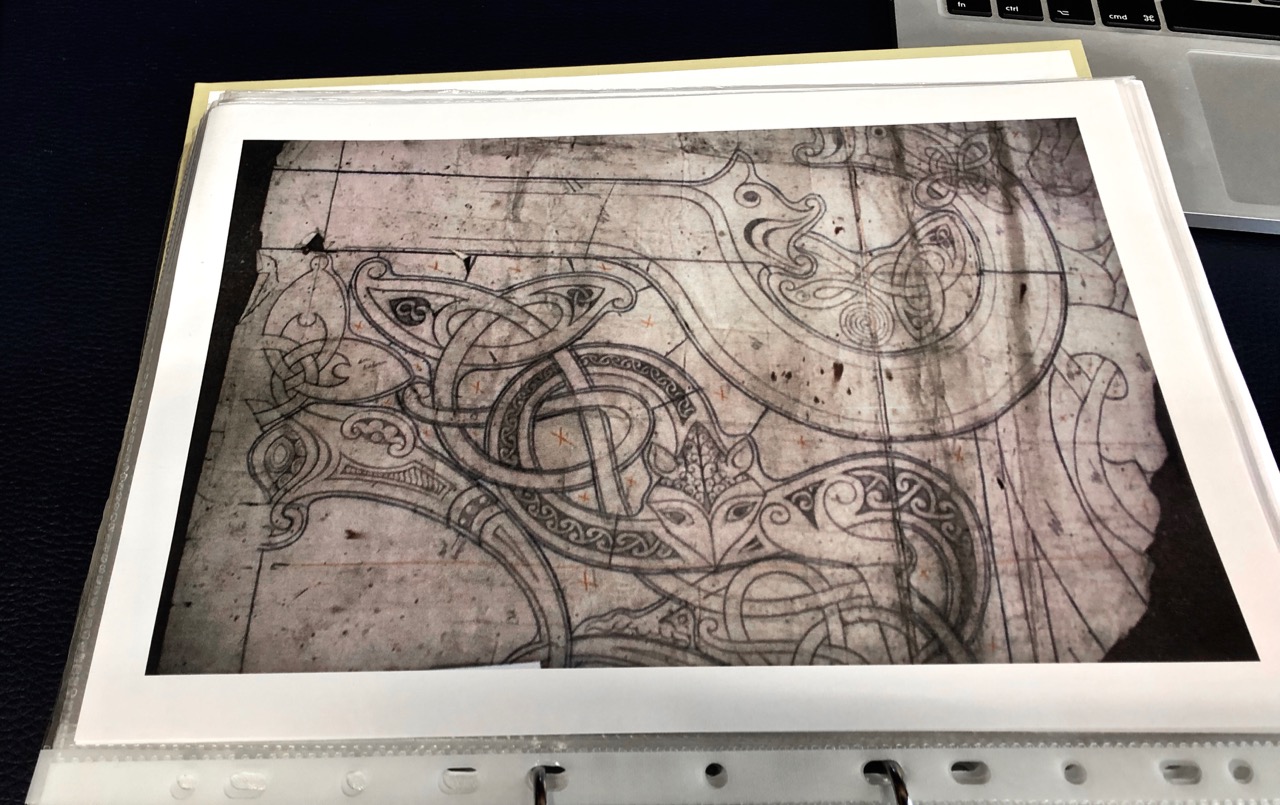

Bartlett’s engraving of the cells at Gougane with the wooden cross and pilgrims paying the rounds

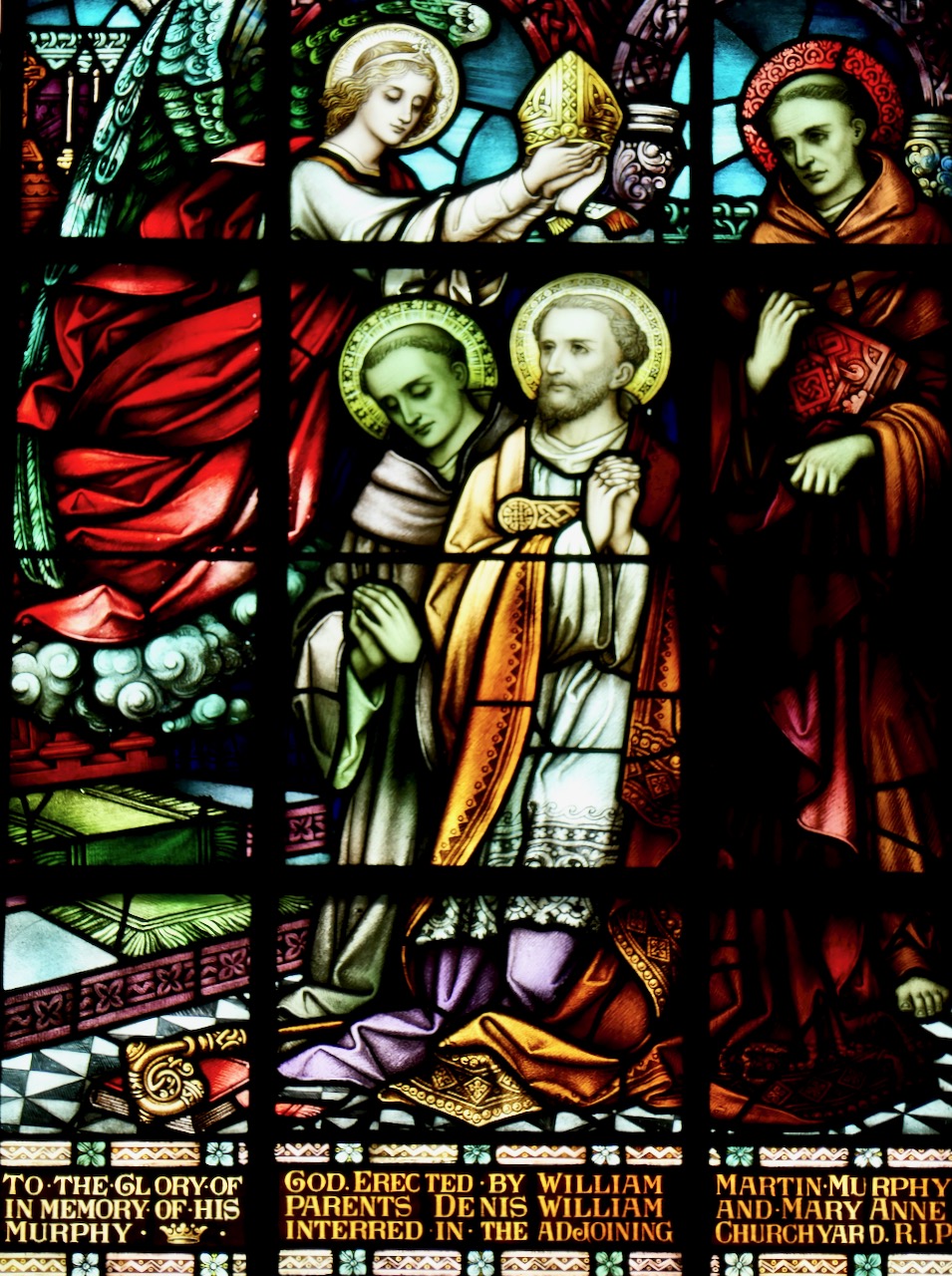

The little island to which St. Fineen Barr retired, alluded to in the legend, was, indeed, an admirably chosen place for the enjoyment of undisturbed solitude, and the indulgence of devout meditation. Several aged trees of the most picturesque forms grow upon its shores, and overshadow the ruins of the chapel, the court or cloister, and other buildings appertaining to them, which cover nearly half the area of the island. In the centre of the court stands the shattered remains of a wooden cross, on which are nailed innumerable shreds and patches, the grateful memorials of cures performed on the devotees who have made pilgrimages to this holy retreat, and by whom this sacred relic is held in extraordinary veneration. Around the court are eight small circular cells, in which the penitents are accustomed to spend the night in watching and prayer.

The ‘cells’ probably date from the seventeenth century, repaired and improved in the 1890s

The chapel, that adjoins it, stands east and west; the entrance is through a low doorway at the eastern end. . . . when we consider their height, extent, and the light they enjoyed, we may easily calculate that the life of the successive anchorites who inhabited them, was not one of much comfort or convenience, but much the reverse—of silence, gloom, and mortification. Man elsewhere loves to contend with and emulate nature and the greatness and majesty of her works; but here, as if awed by the sublimity of surrounding objects, and ashamed of his own real littleness, the founder of this desecrated shrine constructed it on a scale peculiarly pigmy and diminutive. Indeed, while contemplating this and many other unworldly recesses in different parts of Ireland, it is impossible to avoid a conviction, that the wild scenery of those solitary islands and untrodden glens must have had considerable effect in nurturing an ascetic tendency in the minds of religious enthusiasts.

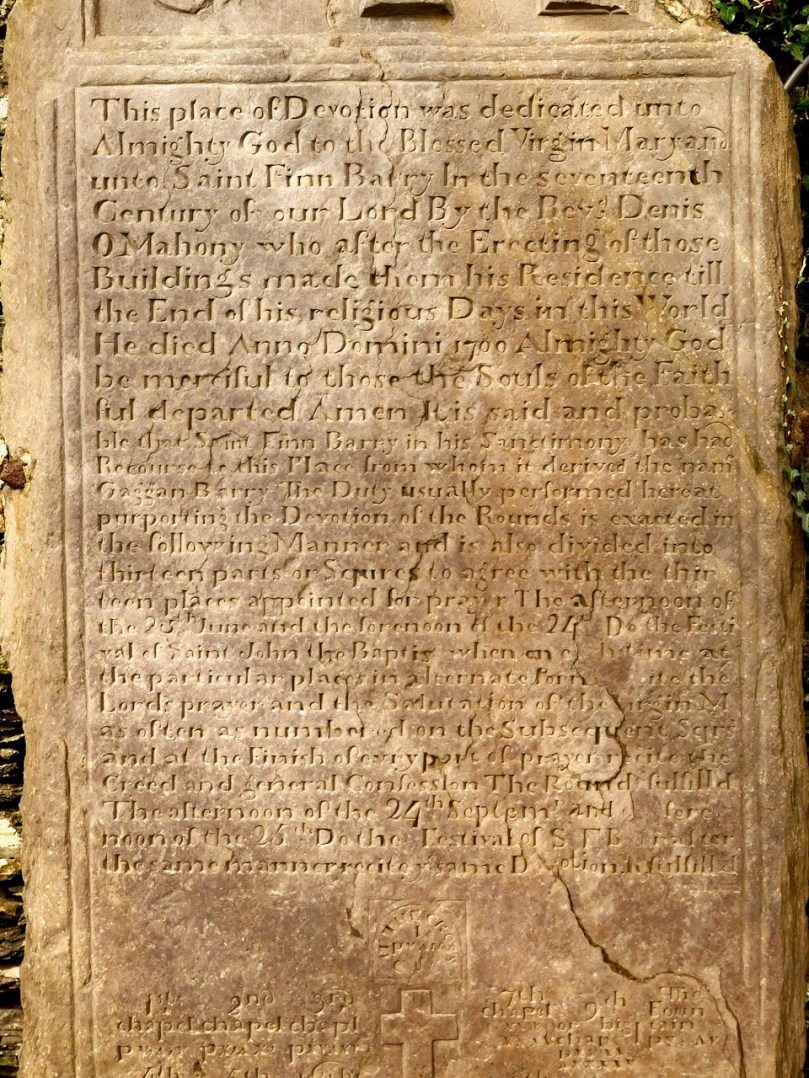

The memorial to O’Mahony, the recluse Coyne refers to, below. It’s certainly more modern than 1728. It’s been found and re-erected since Coyne’s visit.

On the shores of the lake, near to the Causeway leading into the island, a few narrow mounds indicate the unpretending burying-place of “the rude forefathers” of this remote district ; and in this solitary spot, the broken remains of an arched recess mark the last resting-place of a religious recluse, named O’Mahony, who terminated his life here sometime about the commencement of the last century. Smith, the historian of Cork, mentions having seen a tombstone with the following inscription ‘Hoc sibi et successoribus suis, in eadem vocatione monumentum imposuit Dominus Doctor Dionisius O’Mahony presbyter licit indignus’. The flag is not to be discovered now, it either has been removed or is buried in the rubbish of the place. Dr. Smith adds, that O’Mahony was buried in the year 1728.

Coyne’s ‘stepping stones’ (below) are probably this wonderful little clapper bridge

A little to the east of the island, the waters issue from the lake, and form the head of the River Lee, which at this point is so shallow that it may be crossed by a few stepping-stones. From thence it pours its irregular course over huge ledges and masses of rock—now sweeping onward headlong, and now pausing in dark eddying pools through the rugged valley, until it reaches Lough Allua, of which I have already given a description.

The Pass of Keimaneigh (above and below) is fairly dramatic, but I am not sure it quite deserves Coyne’s hype nowadays. It would have been wilder and more picturesque before the wide tarred road

Before quitting this neighbourhood I visited the Pass of Keimaneigh, which, for picturesque though gloomy grandeur, I have never seen surpassed, even in this region of romantic glens and mountain defiles. Through this Pass runs the high road from Macroom to Bantry, having the appearance of being excavated between the precipitous crags, that, rising on either hand, assume the resemblance of fantastic piles and antique ruins, clothed with mosses and lichens, with here and there the green holly and ivy, contributing by the richness of their tints to the beauty of the scene.

Having completed my examination of Keimanheigh, I began to retrace my route to Macroom highly gratified with my visit to these romantic scenes; which, had they been thrown in almost any other part of Europe, would have been a favourite pilgrimage for those lovers of the picturesque, who haunt the Rhine and traverse the Alps, in search of nature in her wild and beautiful solitudes.