Anybody interested in exploring West Cork will have copies of Jack Robert’s books in their libraries. We have several but until this weekend we hadn’t really known the man himself. We were fortunate to be invited along on a field trip organised by old friends of his, on the occasion of one of his visits to West Cork.

Jack arrived from England in 1975 as a fisherman. As he describes it, he was immediately intrigued with the landscape and the deep sense of history he saw all around him. He worked with Martin Brennan at Newgrange and Loughcrew, learning about the ancient monuments and observing first hand the astronomical alignments of passage graves and stone circles. Eventually returning to West Cork, he started to write guides to the ancient and spiritual sites of the area, illustrating them with his own charming and highly accurate pen and ink drawings. Well researched, delightfully succinct and displaying his vast knowledge of the area, these guides came to be prized possessions of those who purchased them. They’re still available, from Jack’s website, from Whyte Books in Schull and other bookstores, and on Amazon.

Jack lives in Galway now and has branched out. His latest book, The Sun Circles of Ireland, covers the whole country, as does his research into Sheela-na-Gigs. He makes jewellery based on prehistoric, Celtic and Early Christian motifs and has a stall in the Galway market.

Our field trip took us into parts of West Cork unfamiliar to Robert and me, to visit a wide variety of monuments. In Inchigeelagh we stopped to examine a strange stone built into a grotto in the grounds of the Catholic church. Listed under Rock Art in the National Monuments site inventory, it is an anomalous piece of carving that is as mysterious as it is interesting. Of course Robert and I can never resist a peek inside churches, and this one contained some very fine stained glass. Lots of lovely windows but my favourite was this one of St Columbanus, an early Irish missionary who founded monastic houses throughout Europe. One of his miracles was to tame a bear – and somehow he ended up as the patron saint of motorcyclists!

A couple of holy wells followed, the first dedicated to St Lachtan had two stone bowls and a large concrete cross. The second was the complete opposite – a quiet little spot in a wood with a simple bullaun stone (more about bullaun stones in a future post), white quartz pebbles, and two cups to use for drinking. It was part of an ancient monastic site of which little remains.

We stopped to walk over an old clapper bridge, recently restored, and tramped through a field to where a standing stone loomed over us, standing guard in the landscape, and ended the day with a visit to a cross slab.

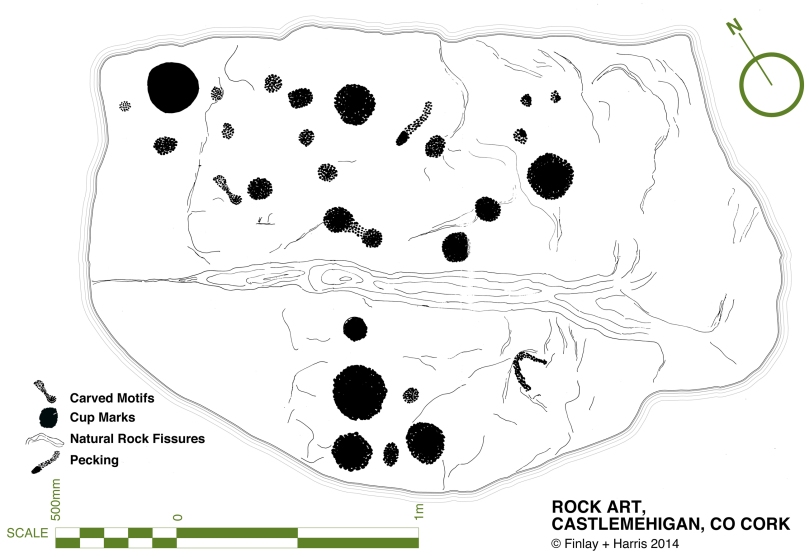

The next day Jack came to us for lunch followed by a trip to the Derreennaclogh and the Ballybane West rock art sites. At Derreennaclogh Gary, the discoverer of this spectacular site, showed us the lines of ancient field fences he is tracing through the bog.

While Derreennaclogh was new to Jack, he had visited the Ballybane site many times and had cleared away scrub there, to reveal hitherto hidden carvings. We were particularly interested to hear this, as my drawings of the site, done in the early 70s, were missing some of the motifs that are now obvious and we had long wondered why.

It’s always a treat to put a face to a well-known name and with Jack it was a rare privilege. We enjoyed very much continuing our education into the wonders of West Cork, through his eyes. We highly recommend his books to anyone who wants to do the same.