There’s a main road between Ballydehob and Schull, and then there’s a back road – a road that meanders through farmland and down half-forgotten boreens, a road lined with wildflowers and dotted with the remains of past history, a road that looks over once-inhabited islands. South of this road lies Mizen Magic 9.

Along the back road in early summer

We’ll start at Rossbrin Cove – a place that Robert has written about over and over, like any writer with his own ‘territory.’ This was the home, in the 15th century, of Fineen O’Mahony, the Scholar Prince of Rossbrin.

Looking down now on what’s left of his castle, it’s hard to imagine that this was a place teeming with life and learning – a mini-university where scribes and poets and translators transcribed to vellum (and to paper – a first in Ireland) psalters, medical tracts and even the travels of Sir John Mandeville. The castle has been in ruins since the 1600s, and we live in fear that the next storm will bring the last of it down.

Rossbrin Castle from the sea

The road runs through the townlands of Rossbrin, Ballycummisk, Kilbronogue, Derreennatra and Coosheen. Ballycummisk has a wedge tomb from the Bronze Age and a ring fort from the Early Medieval period – just to remind you that you are far from the first to want to settle in this place. In more recent times, and like Horse Island, it was once the centre of a thriving mining industry, but a spoil heap and stone pillars are all that remain.

Large ring fort, and the remains of mining activity, in Ballycummisk

Two islands dominate the views of Roaringwater Bay along this road. The first is Horse Island, owned now by one family, with its industrial past a distant memory. There have been various plans for Horse Island in recent years – a resort, a distillery – but so far it has resisted development.

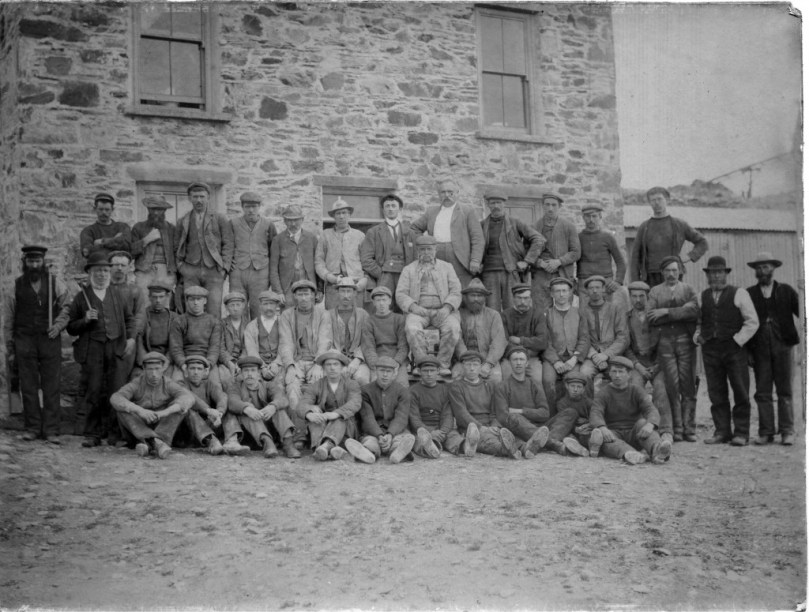

Horse Island Miners in 1898 and the ruins of miners’ dwellings

The other is Castle Island, home to yet another vestigial O’Mahony Castle – one of a string along the coastline, all within sight of each other and sited strategically to control the waters of Roaringwater Bay and their abundant resources.

There’s not much left of the castle on Castle Island

The O’Mahonys became fabulously wealthy in their day, charging for access to fishing and fish processing facilities and for supplies and fresh water. They also forged strong alliances with the Spanish and French fishermen and visitors who plied those waters – a friendship that was to cause great concern to the English crown and that was to spell, in part, their eventual downfall.

Ruined farm houses on Castle Island. The photograph was taken from a boat – that’s Mount Gabriel in the background

The closest spot to Castle Island (also uninhabited) is the beautiful little pier at Derreennatra. There is a large house up behind the pier, now inaccessible but once run as a guest house and famous for its hospitality. A curious bridge once gave access to the demesne and it remains a striking landscape feature, with its pillars and giant Macrocarpa tree.

Derreennatra Bridge

Continuing towards Schull we come to the last of the O’Mahony castles and the best preserved in this area. This is Ardintenant (probably Árd an Tinnean – Height of the Beacon – possibly referring to a function of the castle to alert others to the presence of foreign vessels) and it was the home of the Taoiseach, or Chief, of this O’Mahony sept.

Two ‘beacons,’ ancient and modern – Ardintenant or White Castle below and above it the signal stations on Mount Gabriel

The castle, or tower house, still has a discernible bawn with stretches of the wall and a corner tower still standing. If you want to learn more about our West Cork tower houses, see the posts When is a Castle..?; Illustrating the Tower House; and Tower House Tutorial, Part 1 and Part 2.

Ardintenant is also known as White Castle, a reference to the fact that it was once lime-washed and stood out (like a beacon!) to be visible for miles around. It appears to have been built on top of an earlier large ring-fort which in its own day was the Taoiseach’s residence before the fashion for tower house building.

Sea Plantain at Coosheen

From Ardintenant we head south to Coosheen, a picturesque pebble beach known only to locals. It’s one of my favourite places to go to look for marine-adapted wildflowers. On a rainy day last August I saw Sea-kale, Sea-holly, Sea Plantain and Thrift, and drove back on a boreen lined with Meadowsweet and Wood Sage and past a standing stone whose purpose has been long-forgotten but that continues its vigil through the centuries.

Our final spot in Coosheen is Sheena Jolley’s mill house, now the gallery of this award-winning wildlife photographer. She has restored it beautifully and the gardens are a work-in-progress that manage to capitalise on, rather than overwhelm, the mill stream and the rocky site. This is also the starting point for the Butter Road walk – but that deserves a new post one of these days, a post in the Mizen Magic series. We have written one but it was a long time ago.

Take a walk, or a drive, down any part of this road – do it in summer when the boreens are heady with wildflowers, or do it in winter when the colours of the countryside are at their most vivid. Heck, do it any time!