When we could still walk within the boundary of our own county – and in company – we went with our friends Peter and Amanda in the footsteps of a saint! The walk from Drimoleague to the Top of The Rock – and beyond – is one which has been on our ‘to do’ list for a long time, not least because the first person to do it was our own Saint Finnbarr, founder (in 606AD) and patron saint of Cork city. The motto of University College, Cork is Ionad Bairre Sgoil na Mumhan which means ‘Where Finbarr taught let Munster learn’.

Finbarr is also famous for establishing a monastic site at Gougane Barra in the sixth century, and today you can follow St Finnbarr’s Way all the way from the Top of The Rock to that magical lake in the mountains where you can find an oratory and chapel dedicated to the saint: the full walk is 37km. Our own walk was a mere 3.5km but rewarding nevertheless.

Our walk started at the former Drimoleague railway station. The line opened in 1877, connecting Dunmanway with Skibbereen, and subsequently extension lines went in all directions: to Cork, Bantry, Bandon, Courtmacsherry and – via our own narrow gauge line – from Skibbereen through Ballydehob to Schull. Sadly, all lines coming south west out of Cork have closed, some of the routes surviving until the 1960s. The picture below, dating from 1898, shows the track at Schull Harbour, the most south westerly point on any railway line in Ireland.

Leaving the old station at Drimoleague the path follows the road going north past the architecturally intriguing All Saint’s church, built in 1956. Finola has written about the building and its unusual stained glass (above) – it’s well worth a look inside. Beyond the modern church is the ruins of an ancient one, surrounded by a burial ground which is full of history (below):

After a steep climb we reached our highest point: Barr na Carraige – which translates literally as Top of the Rock. Evidently the first settlement of Drimoleague was established up here and only moved downhill to be more convenient when the railway arrived. At the ‘Top’ we were fortunate to meet David Ross (below) who owns the farm and ‘Pod Park’ here, and has also masterminded the establishment of these walking routes. Great chat was had, and David suggested our best routes for the day as storms had affected some pathways: work is in hand to restore these. We couldn’t leave the ‘Top’ until we had fully appreciated the long views across to Castle Donovan: our own way then headed downwards and along the Ilen River.

Descending from Top of the Rock we were mainly ‘off-road’ on dedicated footpaths. We first met the Ilen River at Ahanfunsion Bridge, a place which has seen a lot of action historically. The name means ‘Bridge of the Ash Trees’. There was a battle here in ancient times and it is said that the victors planted trees at the ford to commemorate the event. The bridge was built originally in 1830 but was blown up in the War of Independence and subsequently reconstructed. It’s a great spot for a picnic and everyone has a good time crossing the stepping stones, hopefully while keeping their feet dry.

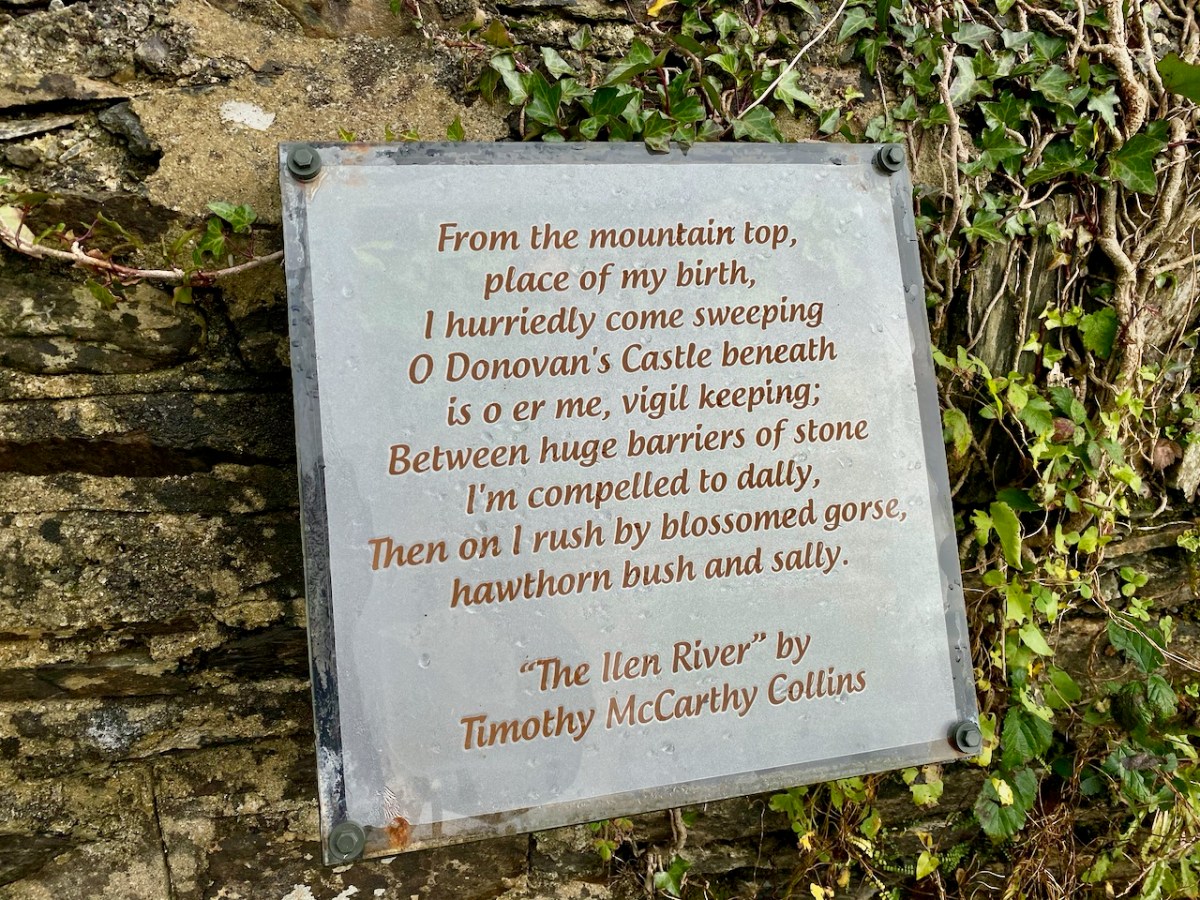

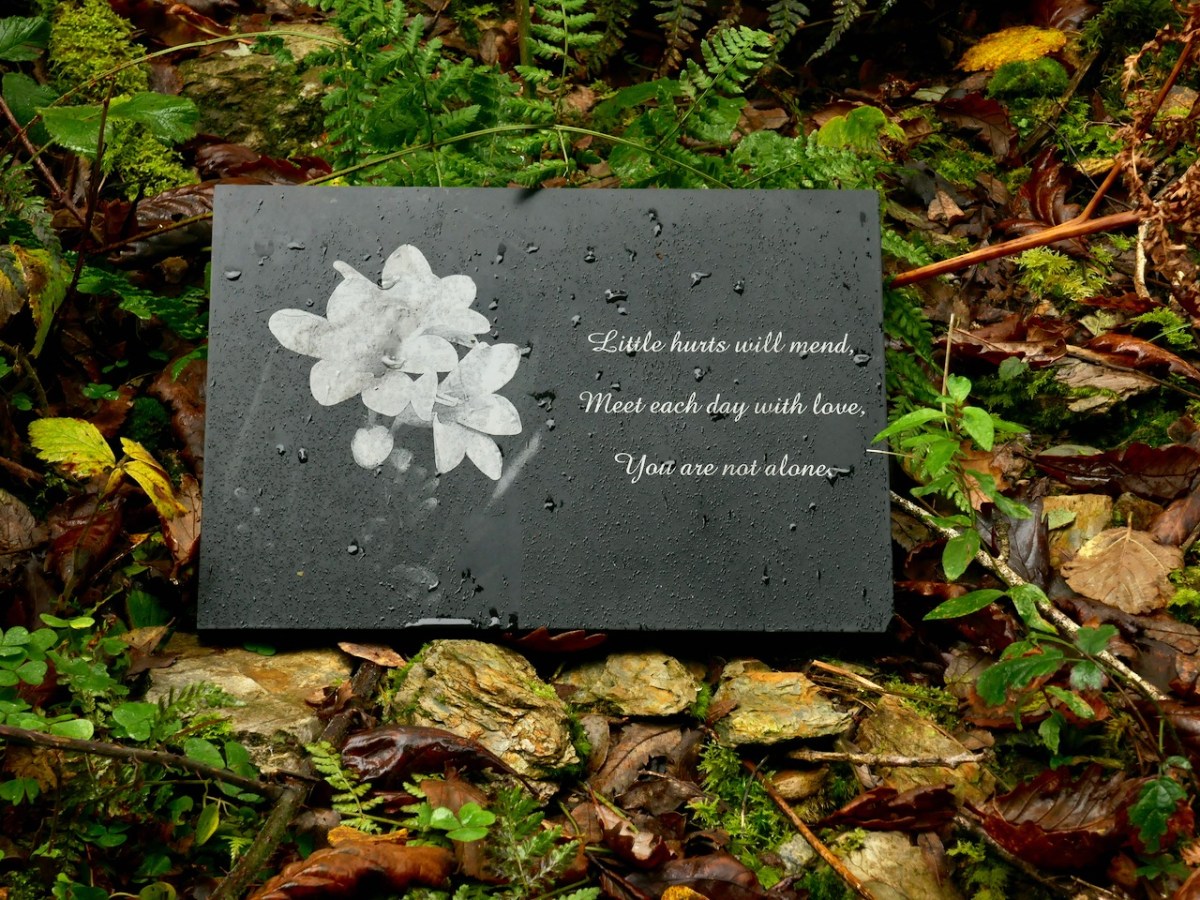

David and his team have worked hard to create and maintain these paths. They have also embellished them with discrete but apposite plaques which include local information and poetry. The work has also involved bridging the river in places to maintain a continuous footpath. We have to commend and appreciate the work they have done and the legacy they are leaving to future generations.

The river walk is truly beautiful, and the wooded valley is quite unusual terrain for West Cork, which is more often high, craggy and dramatic. Wildlife and wildflowers abound, in season. All too soon we came to the boreen which would take us back to our starting point. We are determined to return and follow the network of pathways further when our current restrictions are lifted. We promise we will report back!