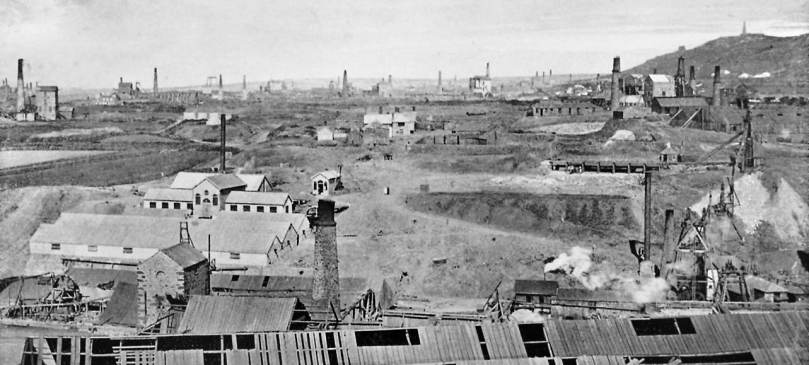

Many of you will know that I was a frequent traveller between Cornwall and West Cork from the 1990s and onwards – until I happily met with Finola and we came and settled permanently here in Nead an Iolair just a few years ago. We have never looked back! But I have often wondered about the various ways in which that journey was made – not just in the last century, but three or four thousand years ago… For we do know that tin mined in Cornwall was brought across to the west of Ireland then, in order to manufacture Bronze – the ‘supermetal’ of those advanced times: it symbolized strength and gave wealth and status.

MV Julia, the car ferry which plied between Cork and Swansea: top picture – in her heyday, when she operated throughout the year. Above – Julia leaving Cork in 2012 after the closure of the Fastnet Line. Her name was changed to Wind Perfection and she became a floating dormitory for workers on the offshore wind farms in the North Sea

Not only tin was brought from Cornwall. A study carried out in 2015 by universities in Southampton and Bristol – (using laser ablation mass spectrometry) – concluded that many of the gold artefacts in the National Museum of Ireland and dating from the Bronze Age were manufactured from gold imported from Cornwall – even though there were rich supplies of gold being extracted in Ireland. Author Chris Standish suggests:

…It is probable that an ‘exotic’ origin was cherished as a key property of gold and was an important reason behind why it was imported for production…

Gold artefacts from Ireland: left – Tyrone Lunula, early Bronze Age; right – Gleninsheen gold gorget, late Bronze Age (photos courtesy National Museum of Ireland)

I would really like to know what type of boat was used all that time ago to bring that precious metal across the Irish Sea. Some have suggested that it would have been a forerunner of the currach – implying a small hide-covered boat. But metal was heavy – even if it was smelted into ingots before the journey: something larger than a currach must surely have been needed. My own not-too-distant memories of having survived a night crossing in the MV Julia, from Swansea to Cork, in a Force 9 storm – with the thudding of huge waves against the steel hull and ominous creakings and crashings coming from the car decks below – lead me to think that any craft that had to traverse those seas in all weathers had to be substantial and sturdy.

A traditional currach in Dingle, Co Kerry – without its covering skin of hide or canvas

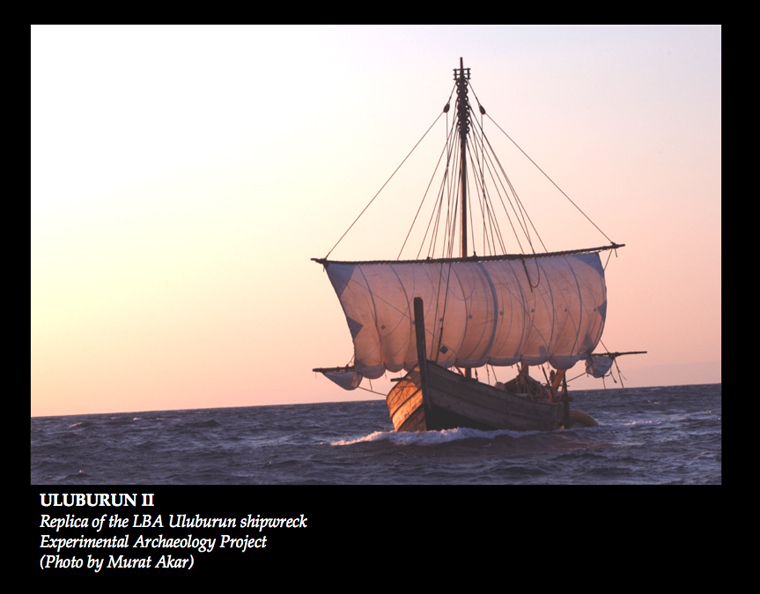

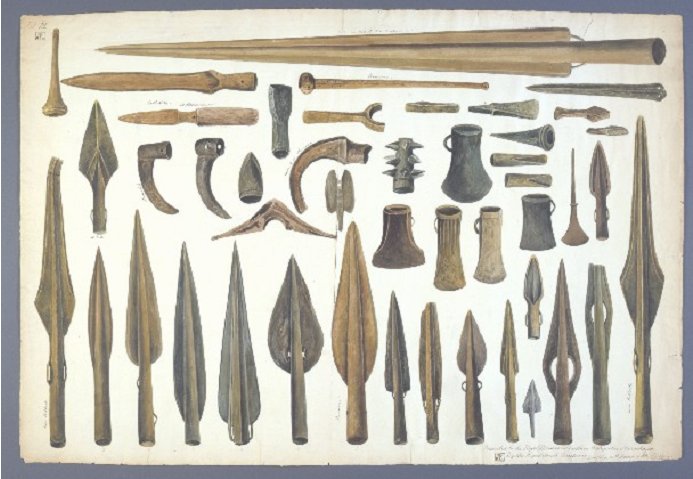

I began to research types of craft that were used in the Bronze Age: examples have been found, some preserved underwater or in bogs. These included ‘log boats’ such as the 14 metre long Lurgan Canoe in the National Museum, which doesn’t seem ideally suited to cargo carrying – especially on open sea. The most likely candidate comes from the Mediterranean: the Uluburun Shipwreck, found underwater in Turkey in 1982.

The Uluburun was a cargo boat: we know this because much of its load was intact when the wreck was found. Amazingly, archeologists were able to pinpoint its route: the ship set sail from either a Cypriot or Syro-Palestinian port and was probably heading for a Mycenaean palace on mainland Greece. It was wrecked in the late 14th century BC. The boat was constructed of cedar planks with morticed and tenoned joints and carried a huge cargo: 500 copper ingots; one ton of tin (which when alloyed with the copper would make around 11 tons of bronze); around 150 Canaanite jars, some filled with glass beads, many others with olives and some with an ancient form of turpentine; 175 glass ingots; African blackwood (ebony); ivory; tortoise-shells; ostrich eggs; Cypriot pottery and oil-lamps; a trumpet; quartz, gold, faience, amber, weapons, tools, pan-balance weights and a gold scarab… The list goes on.

Underwater archaeology: it took ten years to excavate and recover the cargo of the Uluburun vessel

This was in the Mediterranean, not in the Irish Sea. But it’s perfectly possible that the marine technology of those times extended to the northern outposts of Bronze Age Europe. We have to be very clear in our minds that we are looking at a sophisticated society capable of metallurgy, communication and long-distance travel.

Coming back to my own journeys from Cornwall to Ireland, I mourn the passing of the Swansea Cork Ferry, in those days by far the best way to get me and my car to the west of Ireland: I have good memories of arriving in the Lee estuary at daybreak and, excited to be here, watching the sun rise as we sailed up through Cobh to Ringaskiddy. On other journeys I also came over by air: there was a wonderful flight in a small aircraft from Exeter going to Cork. The homespun Devon airport in those days was unsophisticated: on one occasion I lined up to have my luggage checked by security and was asked to take my concertina (a constant travelling companion) out of its case for inspection. I was then asked to play it – in front of the queue – and everything stopped so that the serenade could be heard! It was a small aeroplane – about a dozen seats in the cabin, with the pilot up front – no partition. As he started the engines his broad Cork accent came over the speakers: “…let’s see if we can get this thing off the ground…” He succeeded and – once in the air and cruising at a lowish altitude – got out packs of sandwiches and passed them around. I thoroughly enjoyed watching the outline of Cornwall (exactly as it’s shown in the atlas!) passing below us, to be replaced shortly by the distinctive – and similar – geography of south-west Ireland, soon followed by a sketchy and invariably bumpy landing on Cork’s runaway – especially in any sort of stiff breeze.

Air Lingus Regional flights – operated by Stobart Air – now directly connect Cornwall with Cork. Photo – Trevor Hannant

It’s exciting that – just in time for Uillinn’s West meets West exhibition of Cornish artists, there is finally a direct link from within Cornwall to Cork! A new Air Lingus Regional flight – operated by Stobart Air started operating this month and it’s already popular: extra flights have been added to the planned timetable to cater for higher than expected demand. These flights leave from Newquay Airport and are very reasonably priced. I wish them every success… Back in the day, my journey from Newlyn to Skibbereen via the ferry took all day and a night: the new flight barely takes an hour.

Depart here for West Cork! Newquay Airport, in Cornwall

When the Swansea to Cork ferry stopped running the West of Ireland felt the loss: tourism numbers dropped significantly and businesses which relied on visitors suffered. Things have improved since then, particularly with the Wild Atlantic Way initiative. Hopefully the new air link will lead to increased business between the two western outposts of Britain and Ireland, hearkening back to historical times when close links were first forged. Meanwhile, please don’t forget to come along to West meets West and see the work of contemporary artists from Cornwall. The artists (some of whom will have flown over on the Newquay service!) will be speaking about their work at 12 noon on Saturday 3 June, and I will be giving a gallery talk on Saturday 10 June – also at 12 noon – about the many historic links between Cornwall and the West of Ireland. West meets West – the work of contemporary Cornish artists, at Uillinn, Skibbereen, from 3 June to 8 July. Opening at 6pm on Friday 2 June.