One of the many archaeological excitements in Ireland last summer was the discovery of a hitherto unknown passage grave with significant carvings beside Dowth Hall in the Bru na Boinne area of County Meath. These carvings are likely to date from around 5,500 years ago. In the picture above (courtesy of agriland.ie) from left to right are Minister for Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht Josepha Madigan; agri-technology company Devenish’s lead archaeologist Dr Cliodhna Ni Lionain; Devenish’s executive chairman Owen Brennan; and Professor Alice Stanton.

As you know, we are Rock Art addicts, so this week went along to this year’s Stone Symposium in Durrus, West Cork, to hear Cliodhna, above, give a fascinating illustrated talk on the finds at Dowth. Have a look at this post on the inaugural Stone Symposium from 2017. It’s great that the event is thriving and attracting interest and participants from far and wide.

Our attendance at the Symposium set me thinking about the whole subject of stone. It’s the most basic of creative materials, as relevant today in construction and art as it was to our Neolithic ancestors. Proleek Dolmen in County Louth (above) is an example of the early use of stone to create a structure which made a huge impact on the landscape. It’s a portal tomb over 3 metres high, and the supporting stones are around 2 metres high: the capstone is estimated to weigh 35 tons. It’s probably a more visually impressive structure today – in its ‘naked’ state – than it was when completed, as it is likely to have been covered over with a mound of earth and / or stones. There is folklore attached to this monument: it is known locally as the Giant’s Load, having been carried to Ireland by a Scottish giant named Parrah Boug McShagean, who is said to be buried in the tomb or nearby.

Here’s another portal tomb – the largest in Europe – which I discussed in this post from last year. It’s known as Brownshill Dolmen, and is in County Carlow. Finola is in the picture to give the scale. This capstone is said to weigh 103 tons. The portal tombs demonstrate the use of stone in its rawest and most spectacular state: they are examples of Ireland’s earliest architecture, and we don’t really know what they were for. Perhaps it’s to do with status, either of the builders or of the chiefs or priests who might have been buried in them. They certainly make mighty marks on the landscape…

…As do all the other stone monuments which celebrate their makers – although perhaps they remain enigmatic to us today. Bronze Age stone circles have always fascinated, and at least we know that they have orientations which must have been significant. Drombeg in West Cork (above) is much visited at the winter solstice, when the path of the setting sun falls over the recumbent stone when observed through the two portal stones at the east side of the circle.

While the earliest dwellings of the inhabitants of Ireland thousands of years ago were probably constructed from organic materials – earth, sticks and furze – stone began to play a part in architectural construction in Christian times. The remarkable Gallarus Oratory (above) on the Dingle Peninsula, County Kerry, was long thought to have dated from around the 8th century, although an early commentator – antiquarian George Petrie, writing in 1845 – suggested:

I am strongly inclined to believe that it may be even more ancient than the period assigned for the conversion of the Irish generally by their great apostle Patrick . . .

It’s a fascinating discussion to follow – Peter Harbison sets it out in detail here, and concludes that the Oratory could have been built as late as the 12th century, even after the great Romanesque flowering which included the building of monastic settlements and round towers.

The 12th century cathedral and (possibly earlier) round tower at Ardmore, County Waterford (above), should be a Mecca for stone enthusiasts because of its monumental architecture and carvings: St Declan founded the site in the 5th century, and his monastic cell survives. The Romanesque period in Ireland has many other examples of stone craftsmanship to show, proving that working with stone had become a high art in those medieval times. The examples below are from Killaloe Cathedral in County Clare.

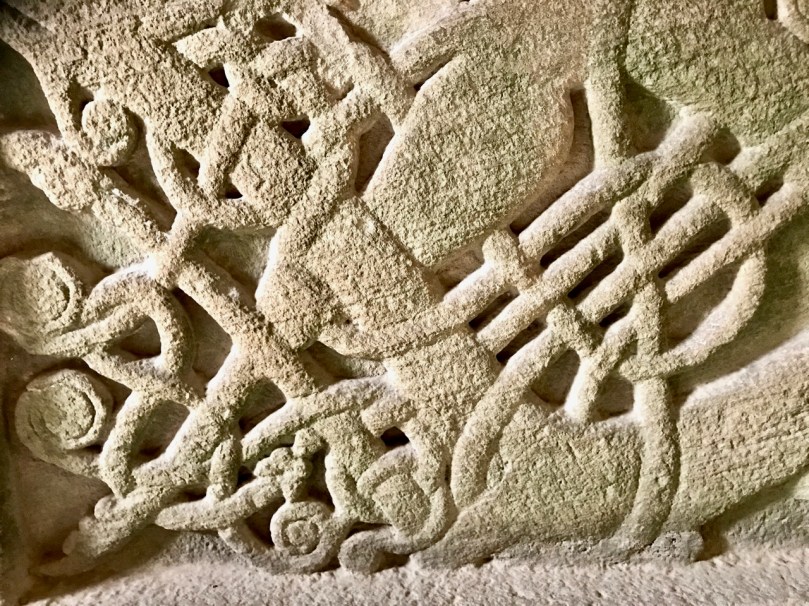

One of the finest Romanesque sites is the Rock of Cashel in County Tipperary. Finola has written in detail on this architectural gem here and here. Suffice it for me to illustrate only one of its treasures – Cormac’s tomb, a sarcophagus beautifully carved in the ‘Urnes’ style – a Scandinavian tradition of intertwined animals.

For centuries, stone has also been a ubiquitous utilitarian building material all over Ireland. ‘Castles’ or – more properly ‘Tower Houses’ – date from roughly 1400 to around 1650, and many remain in a ruined condition, particularly on the coastline of West Cork: we can see five of them from Nead an Iolair. Some have been restored in modern times, including Jeremy Irons’ Kilcoe Castle. The example below is from Conna, East Cork.

Ireland’s landscape is sculpted from stone. Drystone walling is an ancient tradition still practiced for dividing up land, and varies considerably in style regionally, reflecting the differing geology across the island. Two examples from the Beara Peninsula (below) show the essential geometry of field patterns which stone wall building has created over the centuries.

Stone has also long been a medium for communication. We have commemorated our ancestors for centuries with grave markers, often with elegantly carved lettering. Of the two examples below, the first is from Clonmacnoise, and is likely to be early medieval, while the second is an inscription from 1791.

This is just a brief history of our use of stone, dating over thousands of years: I have chosen many examples – almost at random – but hope that I have demonstrated how important it is to continue this ancient craft. The West Cork Stone Symposium is doing sterling work in promoting it today: long may this continue!