As I said in Part 1, this map was made to provide information for the purposes of plantation – that is, colonisation – of Munster, and in particular of those lands forfeited by the Desmonds after their ill-fated rebellions. Jobson, the cartographer who signed this was, according to Andrews, an enthusiastic map-maker who was unusually determined that his maps would survive. Accordingly, he made copies and presented them to likely future employers – hence this one, inscribed to Lord Burleigh, faithful and long-serving eminence grise to Elizabeth 1. That’s herself, below. (Full citation for the map is at the end of the post.)

Queen Elizabeth I, circa 1575 © National Portrait Gallery, London. Used under License*

Andrews says of Jobson:

He also showed unusual zeal in presenting duplicates to likely patrons: no one was going to deprive posterity of a Jobson map by “borrowing” the only copy. Other features of his complex cartographic persona were more distinctly Irish, such as his deceptively slapdash-looking style and his apparent ignorance of earlier Anglo-Irish cartography.

Colonial Cartography in a European Setting:The Case of Tudor Ireland

J. H. Andrews

Much of the ‘slapdash’ nature of the map can be explained when we realise that this map, in fact, was a reduction to small scale of detailed townlands surveys that he, Jobson, and others had carried out, and that he obviously had not been able to make all his observations ‘on the ground’ for whatever reasons. The map was studied in the late nineteenth century, along with a host of other evidence by W H Hardinge. He starts his paper, read to the Royal Irish Academy in 1891, by giving the background to the maps:

So soon, however, as the Queen and her Council decided upon establishing, under certain conditions and limitations, a plantation of her English subjects upon these forfeited territories; and for that purpose determined to grant them out to undertakers, in scopes of twelve, ten, eight thousand, and a lesser number of English acres, it became indispensable to the interests of the crown, as well as to equity in the distribution of the lands amongst the undertakers, to have the area of each town accurately measured, ascertained, and laid down upon a plot or map. Accordingly, I find a commission to that end, bearing date the 19th June, in the twenty-sixth year of the reign of Queen Elizabeth [1584], accompanied by minute instructions from the ministers and lords of Her Majesty’s Privy Council in England addressed to Sir Henry Wallop, Knt., under-treasurer of Ireland, and to other commissioners there, of whom the auditor-general, and the surveyor and escheator-general were two; authorizing and requiring them to make special inquiry in relation to said forfeitures, to measure the demesnes, and to reduce acres to plow lands, according to the custom of the country, and to value the acres rateably according to perches. The survey was completed in the year 1586, and must have been returned into England, as ” The Plot from England for inhabiting and peopling Munster” was soon afterwards sent to the lord deputy. And, further, a very large proportion of the principal plantation grants were passed under the great seal of England almost simultaneously, based upon that survey, and which could not have been so passed unless the guiding information enabling the distribution had been on the spot.

On Mapped Surveys of Ireland Author(s): W. H. Hardinge and Ths. Ridgeway

Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy (1836-1869) , 1861 – 1864, Vol. 8 (1861 – 1864), pp. 39-55 Available here

Hardinge then goes on to comment on Jobson’s Map of Munster:

In a long and expressive marginal note, Jobson sets out his services, stating “that he was three years in her majesty’s service, surveying and measuring part of the lands escheated to the crown in Munster ;” and further, “that Arthur Robinson and Lawson were employed on same survey.” The map in question is genuine, and clearly a reduction by Jobson from the townland surveys, made in pursuance of the pre-recited commission, as a gift likely to be acceptable to Lord Burleigh.

From such accumulated evidence, I concluded that there must have been mapped surveys accompanying the inquisitions and books of survey; and that nothing less could satisfy the exigencies of the plantation – a work that was to be guided by a measure of land up to that time unknown in Ireland, and by a scale of crown rent imposition of three-pence per English arable acre.

In a further note, he cites the cost of the survey as £2,900 – this translates to about £700,000 in today’s money.

This is the frontispiece to Saxton’s Atlas of the Countries of England and Wales. Christopher Saxton was one of the premier Elizabethan cartographers and in this glorious illustration he is showing how indispensable maps and map-makers are to Elizabeth and to the world. Source Wikimedia Commons

Munster in this map refers to the counties of Waterford, Cork, Kerry and Limerick, rather than the present-day province which also includes Tipperary and Clare. Let’s take a closer look now at some more elements of the map, starting with the section on the counties of Cork and Kerry. Two peninsulas (yes – only two!) are clearly delineated, surrounded by galleons. Note the two crests, one with a harp and the other with the English cross of St George, both bearing the regal motto of Honi Soit Qui Mal Y Pense.

Honing in to take a closer look at the green area (below) labelled the Counte (County) of Desmond we see that the principal families names are Macarte Moor (McCarthy Mór)), who were the overlords of West Cork, and O’Swellivan Bear (O’Sullivan Bear) on the south coast. Below is Donal Cam O’Sullivan Beare – the very man named on the map – read more about him in An Excursion to Dunboy.

Bere Island is Illan Moor (Illaun Mór, which is its traditional name – Large Island – as it is, in fact, Ireland’s largest island). Whiddy Island is called Illanfoyde, and is assigned to the O’Sullivans. All around Bantry is assigned to Rogers, a completely unfamiliar name, although one of our commentators last week noted that there is a strand there called Roger’s Strand!

That whole green area is odd, though, isn’t it? In fact, the Beara and Iveragh Peninsulas are shown as one large landmass, with the Beara marked off by an orange line. Here is the surest evidence we have that this map was not drawn on the ground (or by sea) using actual observations and measurements. The coasts and hinterland of both these peninsulas must have presented formidable obstacles to cartography and reminds us that mapping was a dangerous profession in Elizabethan Ireland.

The dangers are starkly revealed in an account by the Attorney General who related that Richard Bartlett, ablest of all the Queen’s Anglo-Irish cartographers, was beheaded in Donegal in 1609 “because they would not have their country discovered”.

how ireland was mapped By Rose Mitchell Map Specialist, The National Archives

And if it wasn’t the natives, then it was the arduous work of surveying these wild lands that challenged the map makers. This was highlighted by the story of Robert Lythe, an English military engineer who almost went blind and lame while serving in Ireland from 1567 to 1571.

Dingle (in red), however, is a different matter – it has assumed outsize proportions, probably an indication of its importance in the Desmond Rebellions. There are many more place names on it than there are on the green mass. Ventry and Smerwick Harbours are indicated since both were important sites of resistance in the Desmond Rebellions – the barbarous massacre of Spanish and Italian allies at Smerwick was one of the decisive acts in the war, and involved such luminaries on the British side as Black Tom Butler, Earl of Ormond (below), Walter Raleigh and Edmund Spenser. Ventry was where the English troops entered the peninsula.

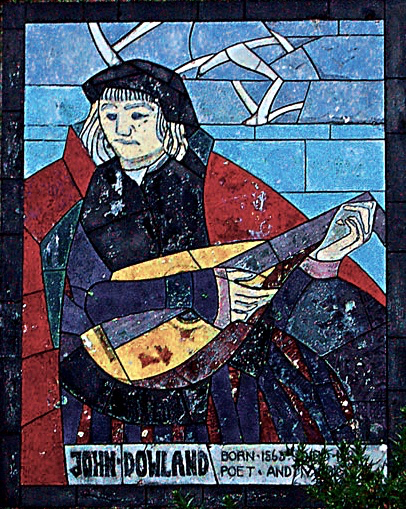

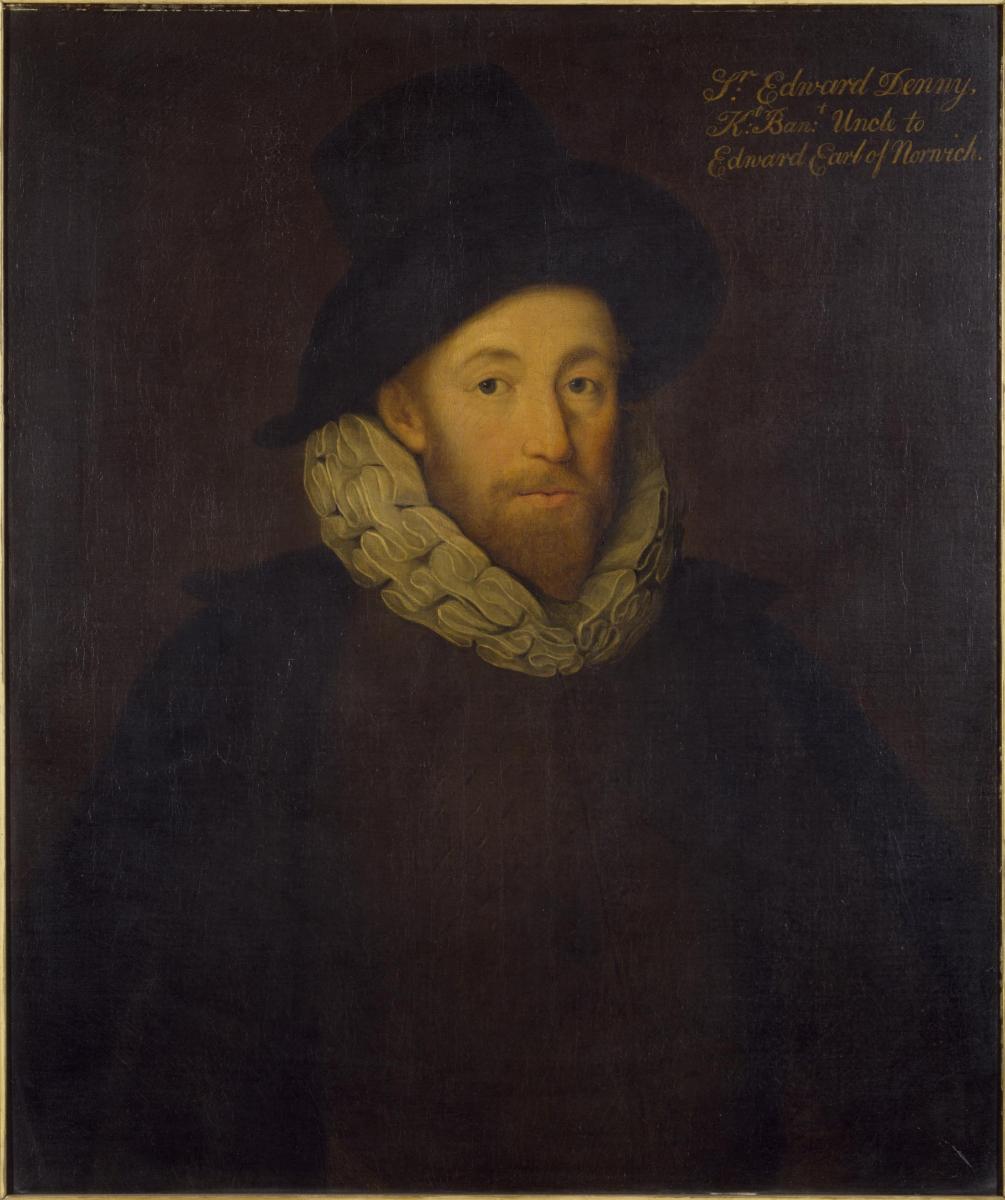

The Bay of Tralee is noted and the area around it is labelled DENE – this refers to the lands granted to Sir Edward Denny (below). I have written about the extraordinary story of the Dennys and their tenure in Tralee – a story that culminated in Ireland’s Newest Stained Glass Window. And by the way – can you see Sliabh Luacra at the bottom of this section – the home of a distinctive tradition in Irish music.

Whew – better end there for today. As you can see. we have barely scratched the surface of what can be gleaned from this map. Perhaps we will revisit it in a future post – but for now I leave you with the tip of the Dingle Peninsula, slightly expanded from the lead image, so you can try your own hand at making out what an Elizabethan planter might have been vitally interested in.

Coliemore Harbour in Dalkey – does it look like Elsinore?

Coliemore Harbour in Dalkey – does it look like Elsinore?