Clonfert is only a couple of counties over from us: we just have to skip through a bit of Cork and Tipperary and there we are in Galway – a tiny corner of it that is shaped by the River Shannon. So, on a Thursday afternoon at the beginning of June, we found ourselves tripping along dead straight boreens – narrow for the most part – taking us through lush dairy lands – on a quest to revisit Clonfert’s medieval Cathedral, and its associations with one of Ireland’s most famous saints: Brendan the Navigator.

As we approached the little settlement of Clonfert, our empty road ahead was interrupted by a small white car, which seemed to travel erratically from one side of the lane to the other, and our arrival made little difference to its progress. As we got near, we realised that there was a wiry Jack Russell ambling along the road in front of the car: it was clear that the terrier was having its daily walk, with the owner driving along protectively behind it, regardless of where its fancy might take it. Ah, sure – we were in no hurry, so we joined the procession and waited as the dog sniffed and shuffled its way back home: eventually, dog, car and owner vanished through a gate, and we had the road to ourselves once again . . . This is life in Ireland, and it’s good!

Clonfert’s grandly styled ‘Cathedral’ is so important historically, yet it could hardly be more remotely situated. From the east (upper picture above) it looks like many another Church of Ireland building, maybe not worth a second glance – unless, like us, you can’t resist examining every unturned stone because there is invariably something unexpected to be found under it. Just turn the corner and have a look at the west entrance door:

That doorway, with its exquisite decoration dating probably from the 12th century, has been described as ‘the supreme expression of Romanesque decoration in Ireland’. The carvings, although suffering from hundreds of years of wear and tear from the Irish elements, still display an extraordinary richness and variety: we can only wonder at the inspiration, skill and knowledge of the carver, who must have been deeply immersed in both lore and craft. Tadhg O’Keeffe, current Professor of Archaeology at University College Dublin, suggests a date of c1180 for this doorway. Records state that the church was burnt during a Viking raid in 1179, the same year in which a synod was held there by St Laurence O’Toole; installation of this imposing entrance may be connected with these events. Finola’s post today also explores Romanesque carvings not too far away, at Clonmacnoise. She has also written on Clonfert’s architecture in her Irish Romanesque series.

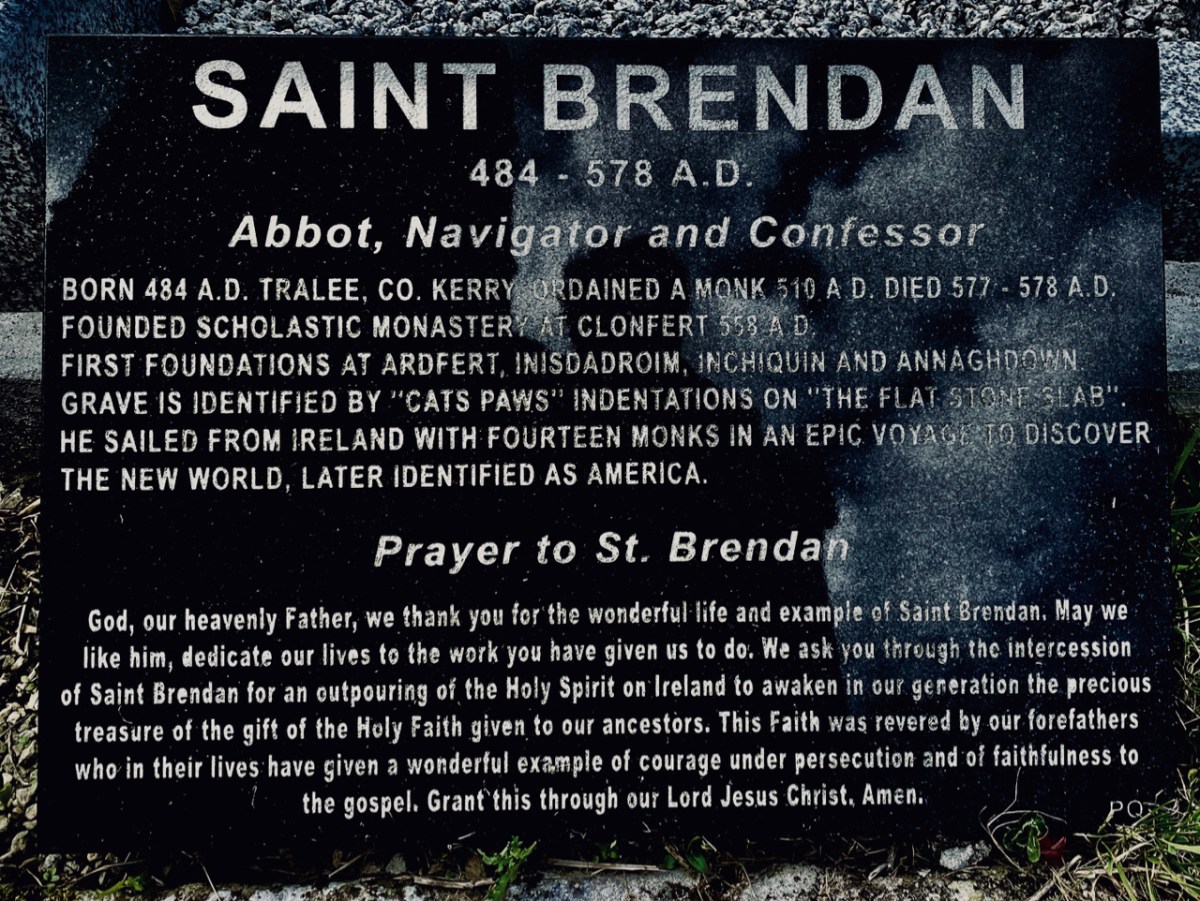

St Brendan lived from 484 to 577. We saw his birthplace in Fenit, Co Kerry, a few years ago. He founded many monasteries in Ireland but arranged for his body to be taken secretly to Clonfert Cathedral for burial as he didn’t want his remains to be disinterred by relic hunters. His grave is a stone slab just outside the great west door. On it are said to be the marks of cats’ paws – interestingly linked, according to folklore, with the many carvings of cats’ heads on the doorway arches.

When we first visited Clonfert, many years ago, the cathedral itself was closed and we went away with the impression that we had seen all the wonders that the place had to offer by our explorations of the outside of the building and its setting. We were wrong: on this occasion the door was unlocked and there were unexpected treats hidden for us in the interior.

Further carvings decorate the church walls: they vary in date and style, but all are fascinating. Here is a selection – notice the seemingly random arrangement of heads and animal features on the great 15th century chancel arch, above.

Angels, cross-slabs, a wyvern and, astonishingly, this fine mermaid complete with comb and mirror. I have found very little information to identify why these various carvings are found here in the Cathedral, apart from general legends which suggests links with Saint Brendan.

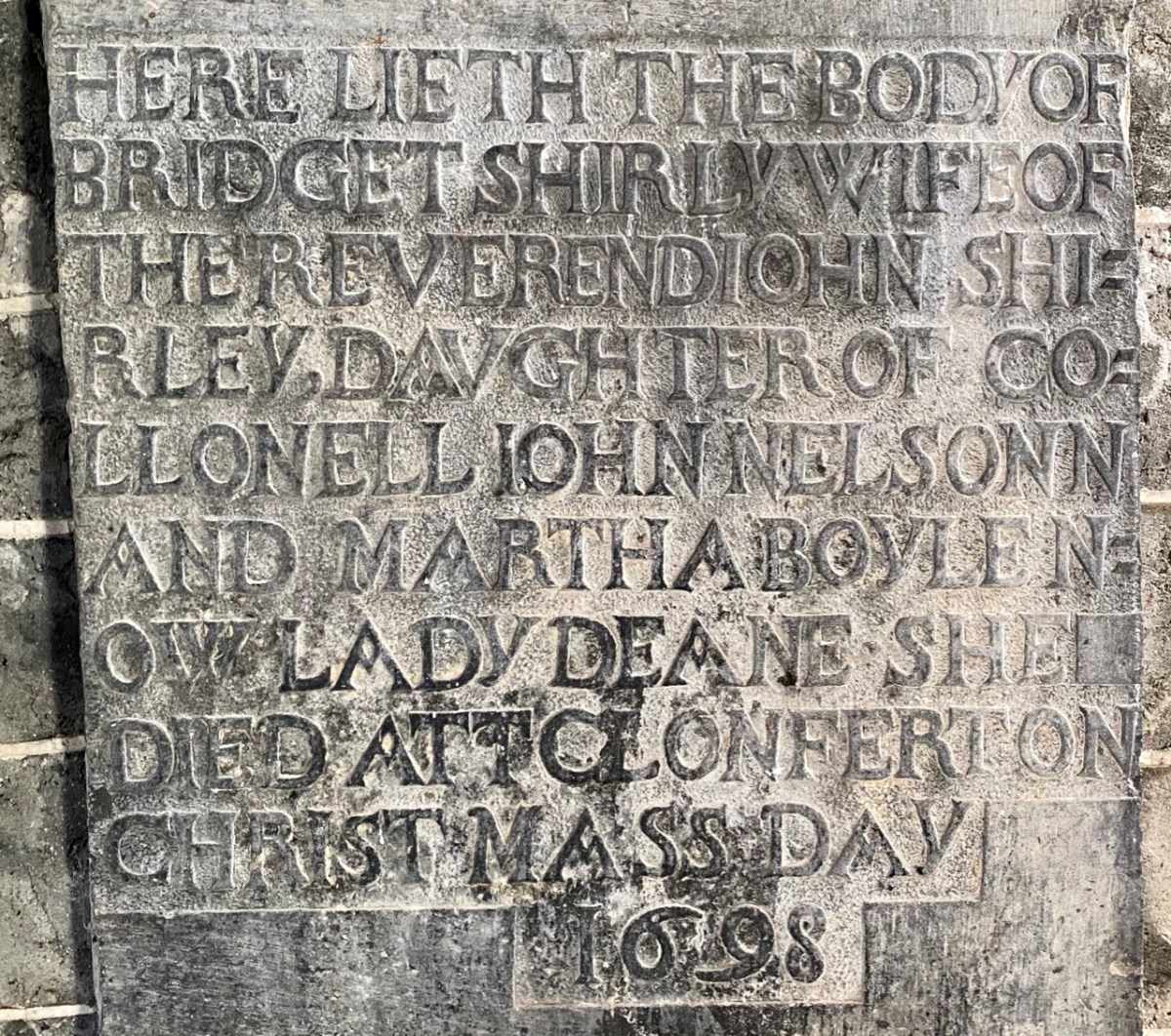

The carved stone head was found ‘in the ceiling’ when restoration work was carried out in 1985. It is said to date from around 1500, while the ancient and beautiful font is attributed to the thirteenth century. We could linger and feast on further treasures inside the church, but we need to look at the surroundings, which reveal yet more history.

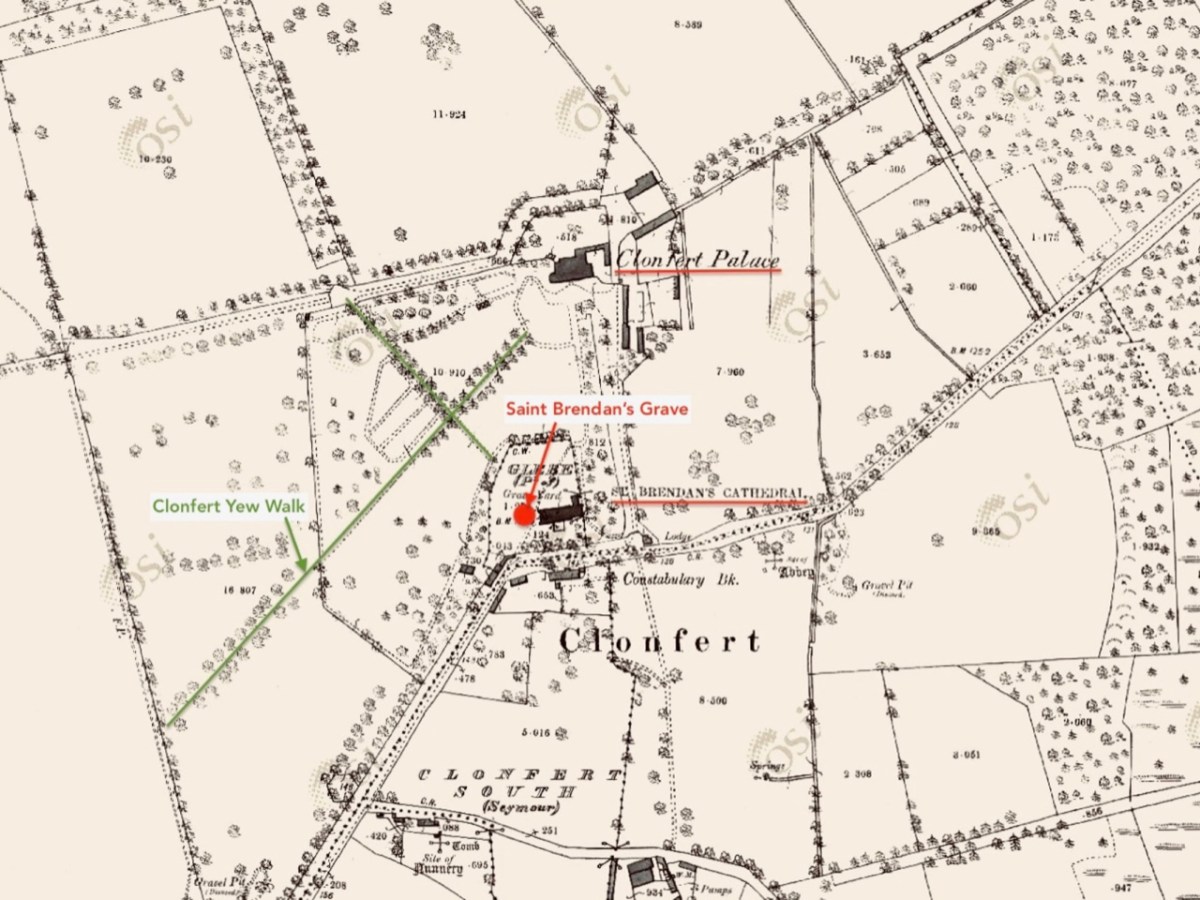

This extract from the 25″ OS map – late nineteenth century – shows the cathedral and some of the landscape features associated with it. We came here a few years ago, when we were researching Ireland’s waterways, following in the footsteps of English writer L T C Rolt. In his book ‘Green & Silver’ we read of his admiration for Saint Brendan, and his determination to find the grave at Clonfert, which he did in 1946. His book is illustrated with photographs taken by his wife Angela, and the one picture from Clonfert which is used in the book is this one of the ‘Yew Walk’ which was laid out as part of the gardens of the Bishop’s Palace, which you can see marked on the map.

Our own photo of the Yew Walk at Clonfert was taken a few days ago. You can see that it survives, although neglected today. Some of the yew trees are said to be up to 500 years old. From the map you can also see that the Yew Walk connected the Cathedral to the 16th century ‘Clonfert Palace’, and was set out as an ornamental cruciform route, suggesting the path that might have been taken by the monks a thousand years ago. When we explored previously, we discovered the ruins of the Palace at the end of the Yew Walk, and wondered why it has been left in this state (since 1954, as we subsequently learned). The answer to that is fascinating, and I urge you to read my full account from that first visit, here. Below is a photo dating from c1950, showing the Palace at that time (with thanks to Dr Christy Cunniffe). My own photos from this week’s visit follow.

Clonfert might have been a very different place today if Queen Elizabeth had been listened to:

. . . We are desirous that a college should be erected in the nature of a university in some convenient place in Irelande, for instruction and education of youth in learning. And we conceive the town of Clonfert within the province of Connaught to be aptlie seated both for helth and comodity of ryver Shenen running by it . . .

Queen Elizabeth, Letter to the Bishop Of Clonfert, 1579

The Queen’s advice was not taken up, and Trinity College Dublin was established instead – in 1592 – becoming Ireland’s first University.

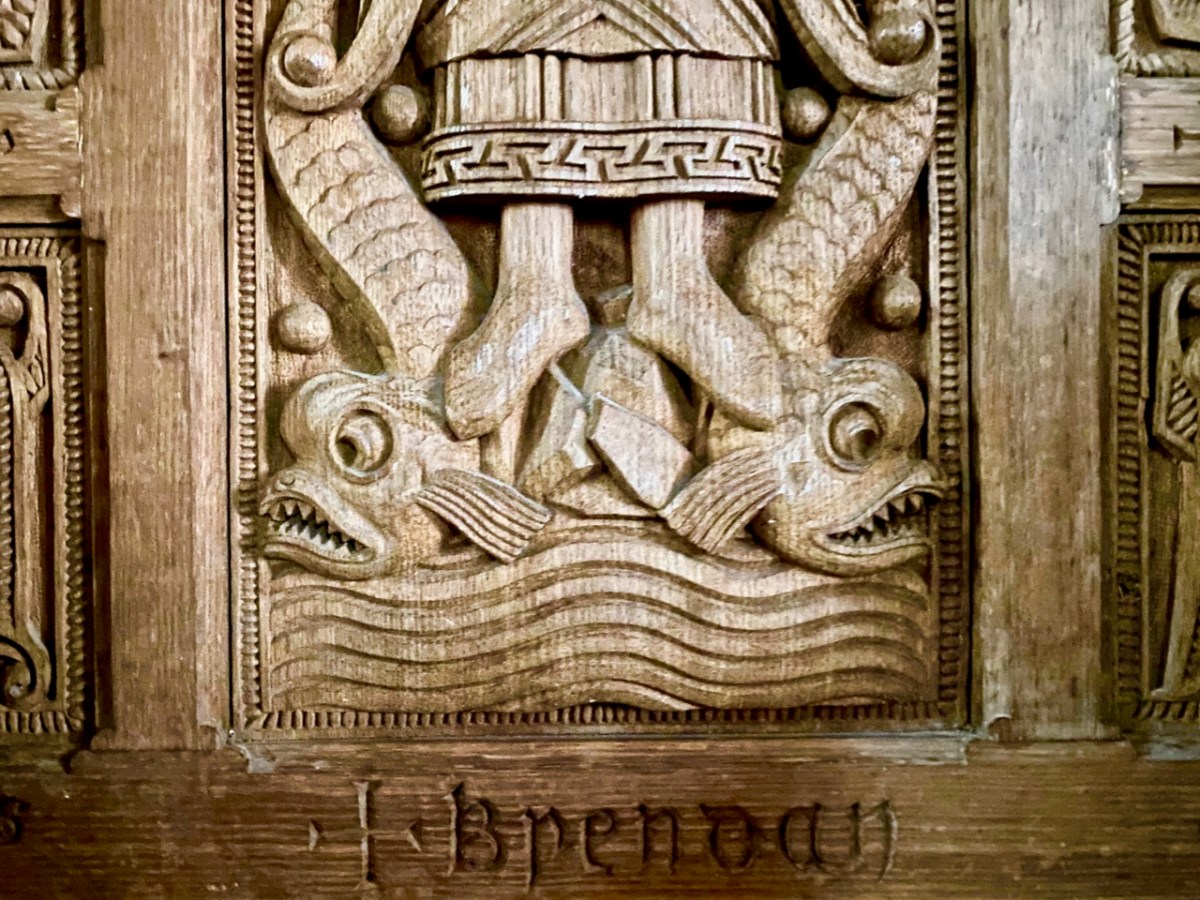

The site at Clonfert is so interesting – and covers so many periods in Ireland’s history – right up to the 20th century. It was well worth revisiting – and will merit further visits in the future, too. I’ll leave you with one aspect that probably impressed us most this time around. It’s the Bishop’s Throne which is hidden in the shadows of the Cathedral chancel. Carved from oak, most likely in the 19th century, it is a wonderful representation of Saint Brendan himself, surrounded by the Four Evangelists, crafted in the style of the Book of Kells. Look at him, also, on the header. Here is the Irish saint who set sail out on a voyage into the unknown – seeking Paradise – and discovered the World!