It’s been too long since I started my series Ireland 50 Years Ago, intending to update it regularly. We had been gifted a complete set of Ireland of the Welcomes from the 1970s, and my first three posts reflected on what was seen as important to highlight about Ireland, to the word, 50 years ago. Alas, my good intentions got derailed by all kinds of other interesting topics, with the result that 1972 got left out altogether. What I’ve decided to do is go through the six 1972 issues now and pick out one thing from each issue to highlight. It’s a quirky selection of things that appealed to me for various reasons.

January-February

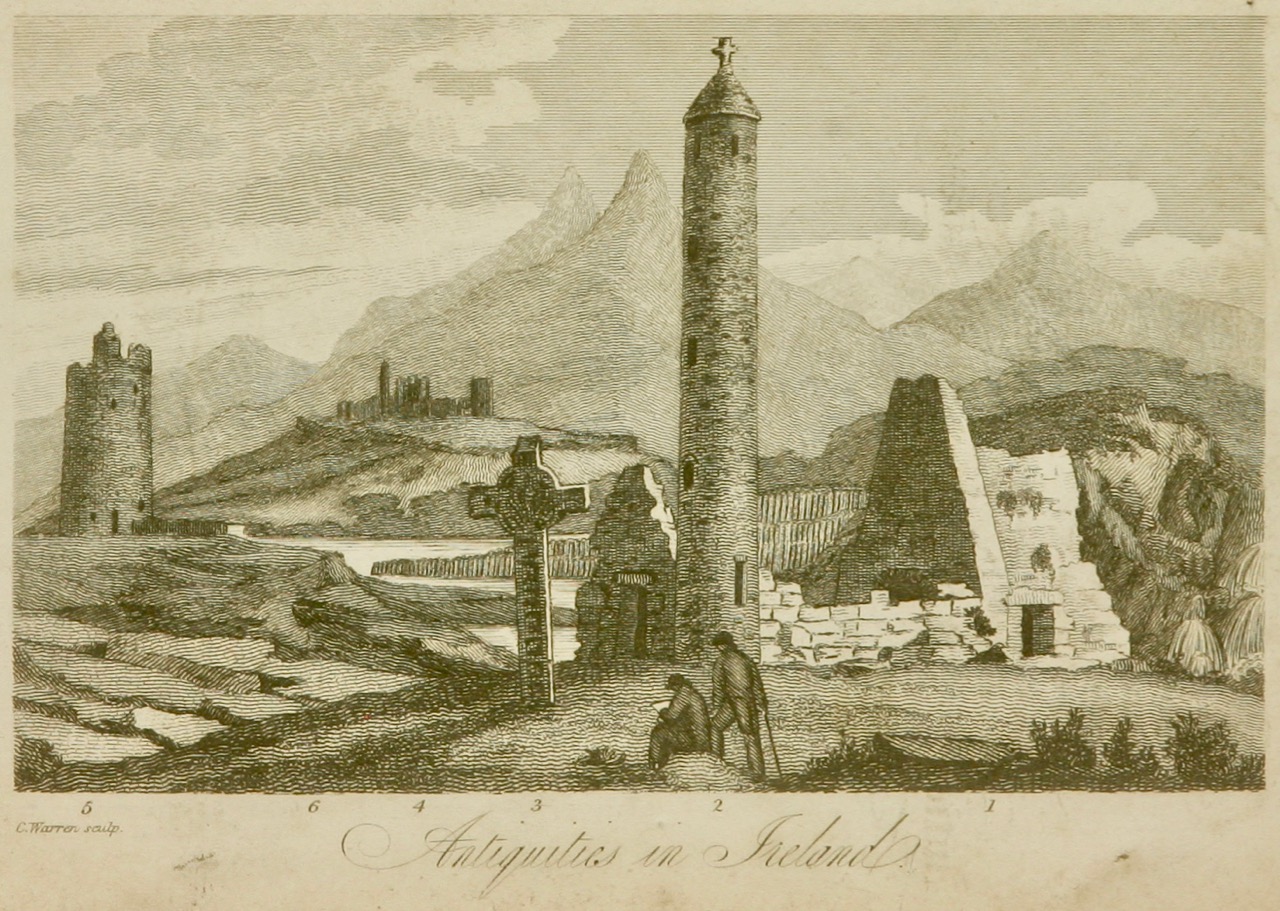

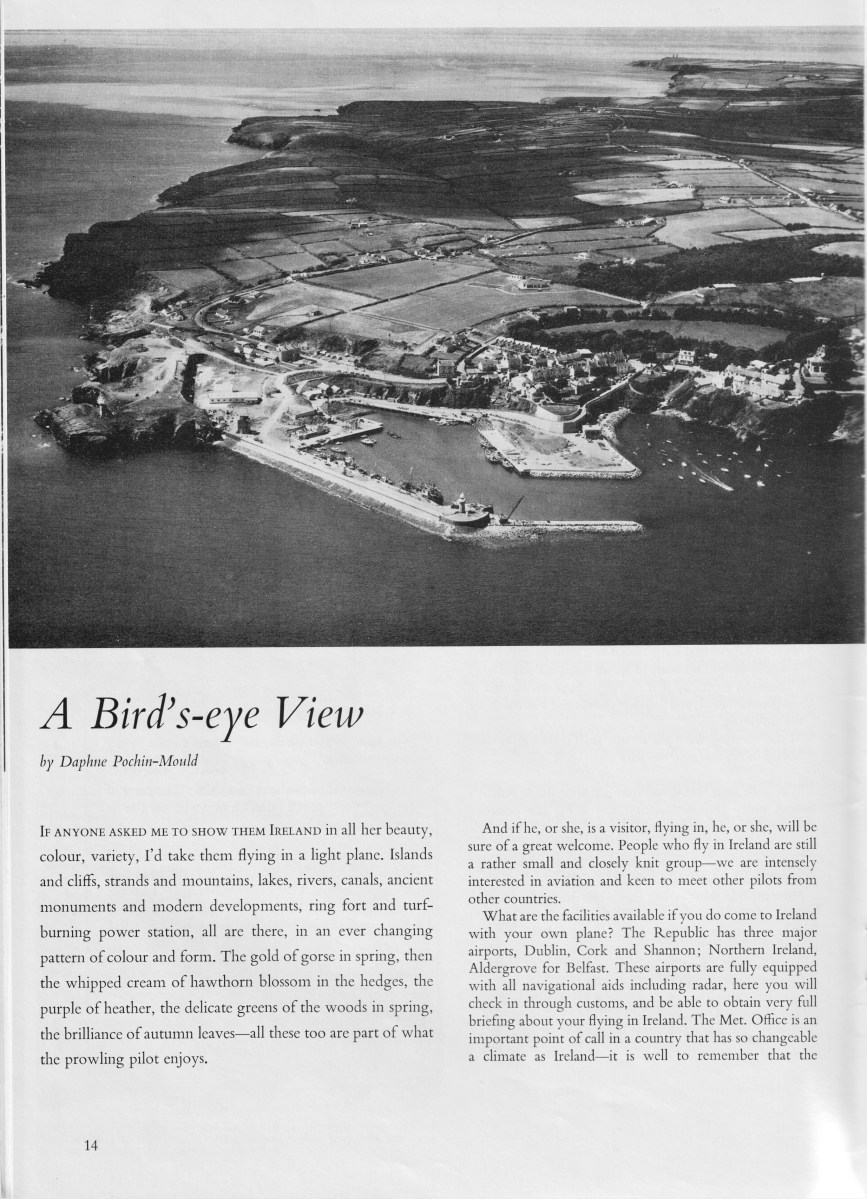

Daphne Pochin-Mould was a hero to us in the Archaeology Department at UCC in the early 70s. She came occasionally to do a slide show of her aerial photos, and I have a hazy recollection of going to her house in Aherla. We knew then she was an amazing woman, but I hadn’t realised just how amazing until I read her entry in the Dictionary of Irish Biography.

March-April

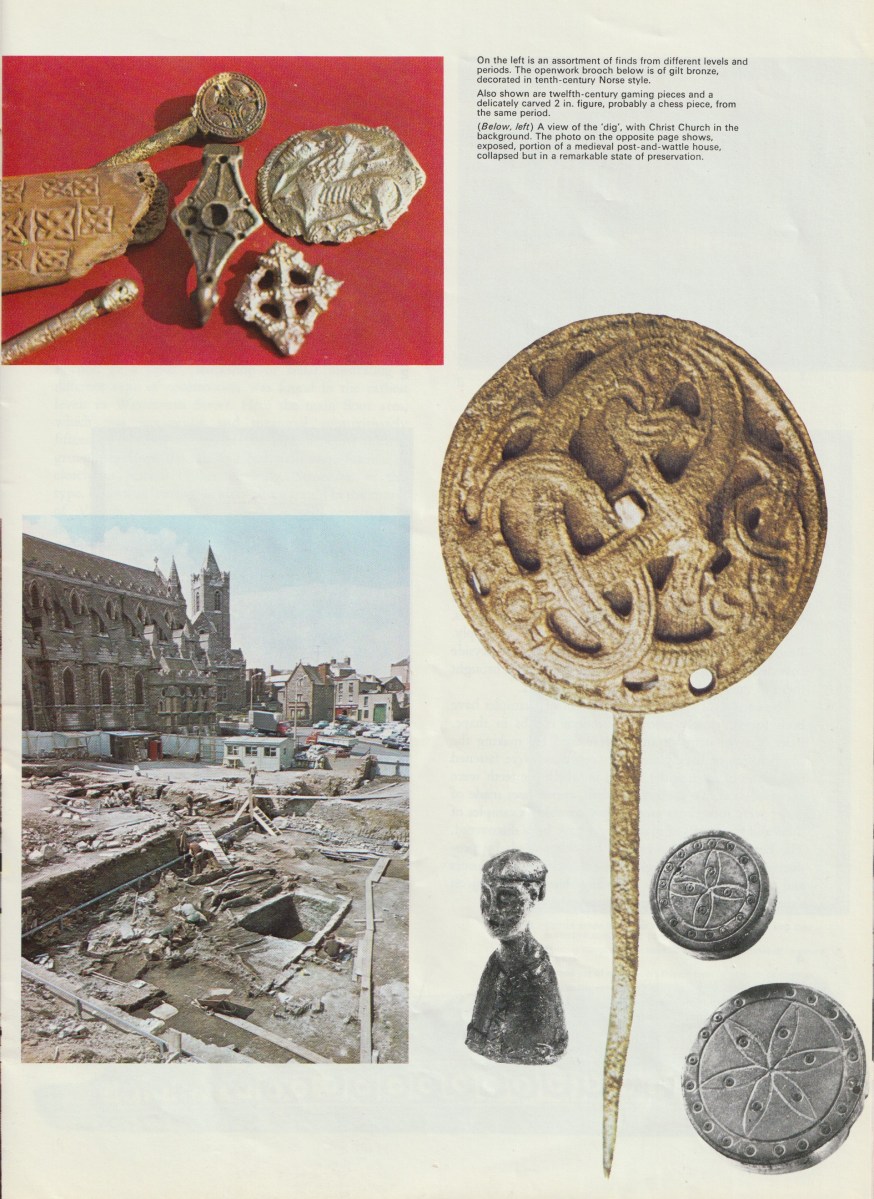

Viking/Medieval Dublin – Excavations by the National Museum of Ireland by Breandán Ó Riordáin

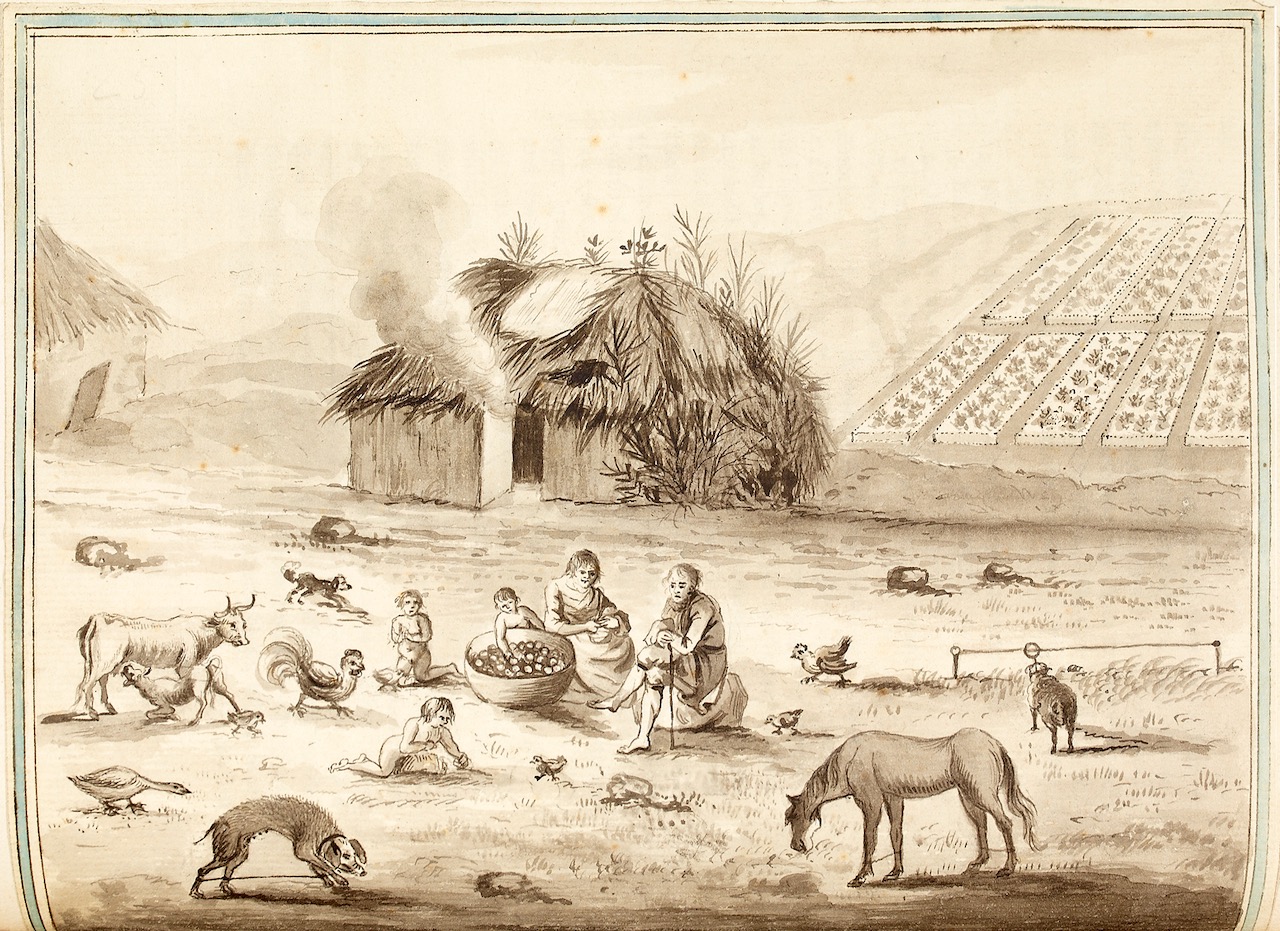

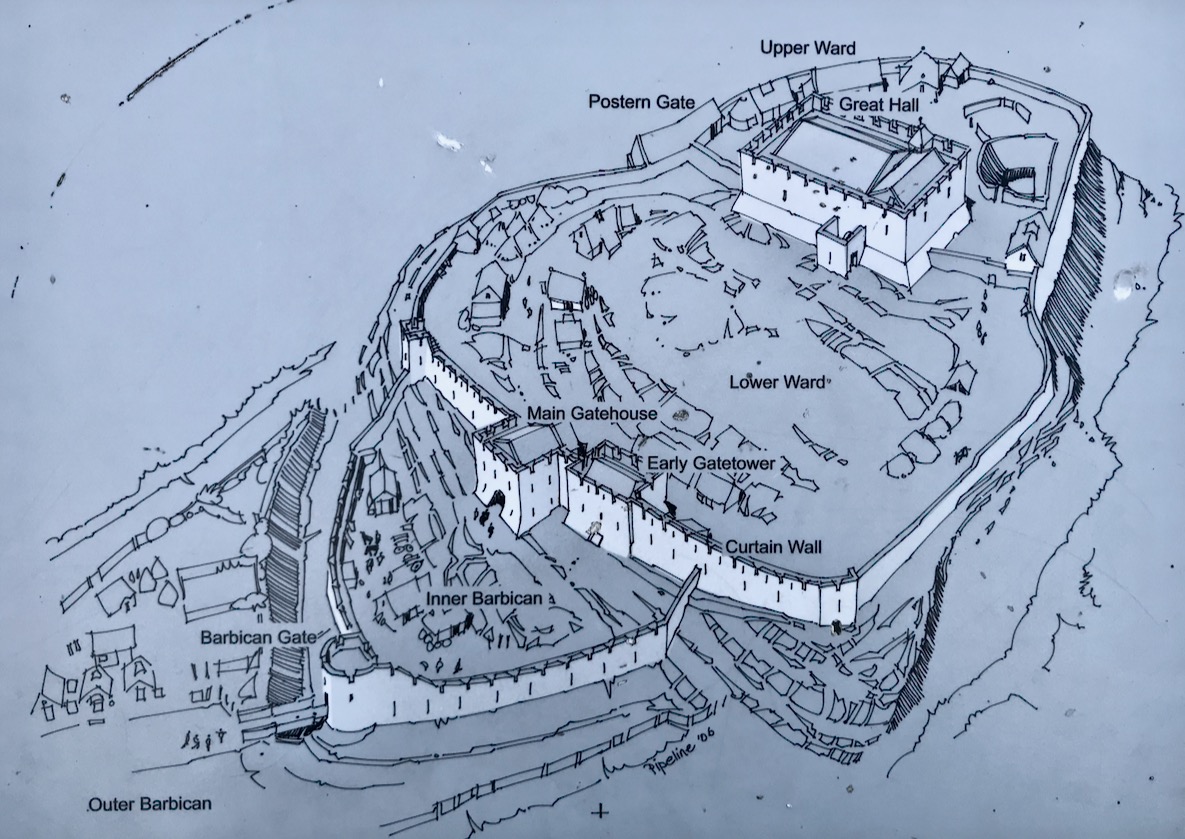

This was not the infamous Wood Quay excavation, which came later, but an ongoing investigation by the National Museum located around High Street and Winetavern Street. Ó Riordáin described the Viking artefacts that were found, and the good state of preservation that were the result of burial under a dark-coloured peaty layer of debris that had accumulated over hundreds of years. Houses, with central hearths, were “formed of upright posts with horizontal layers of wattled or rods (generally of Hazel, ash or elm) woven between them”. Carved bone trail pieces were evidence of ‘schools’ of artists. The Norman period of occupation left a very well-preserved assemblage of artefacts too – including this shoe.

May-June

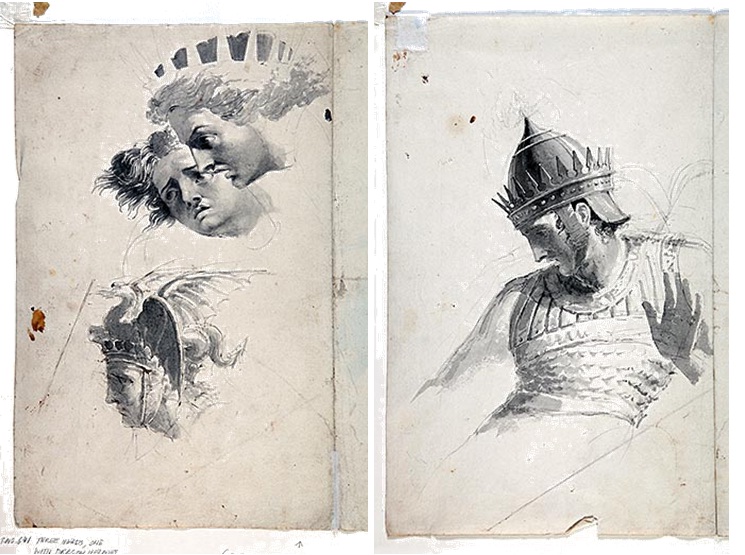

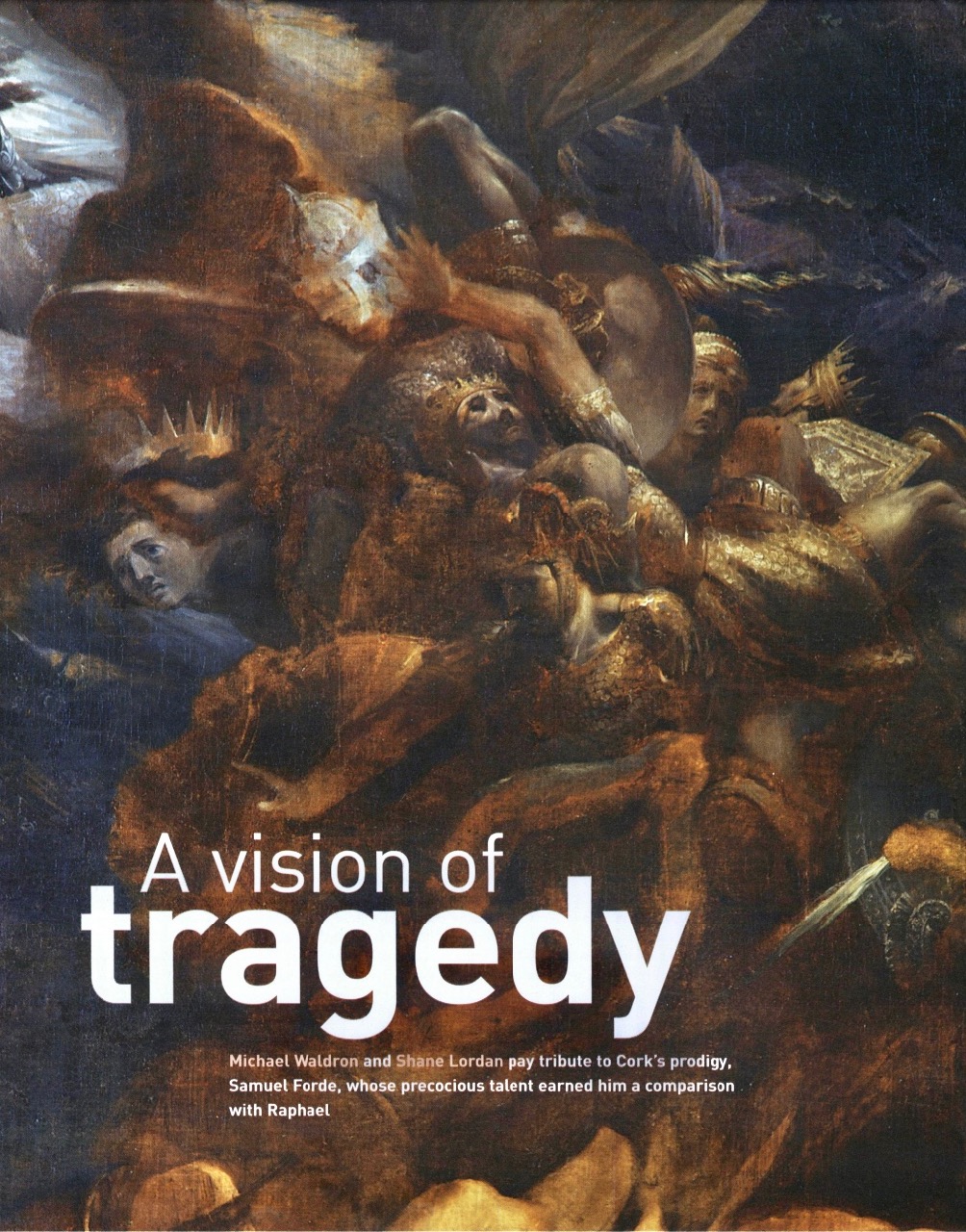

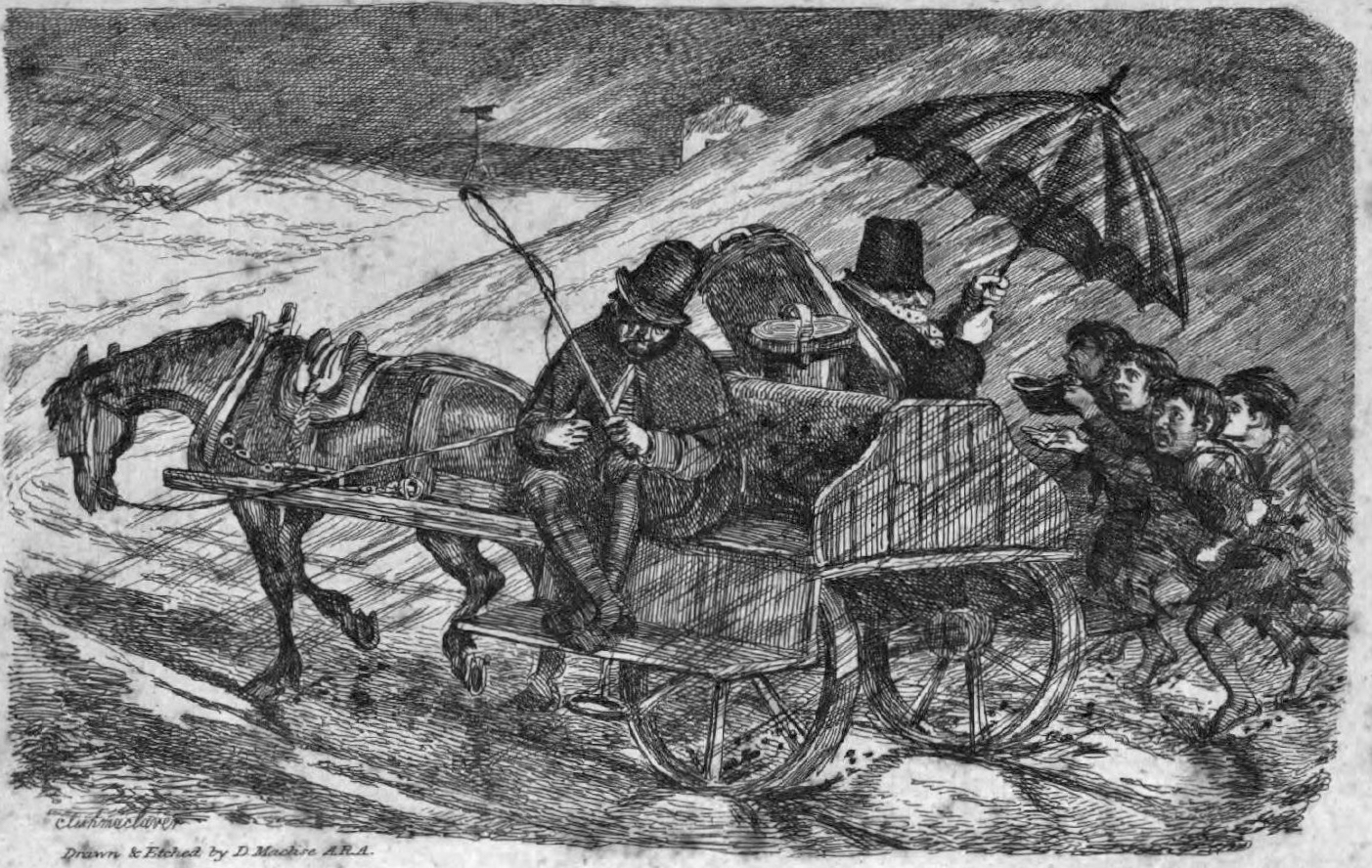

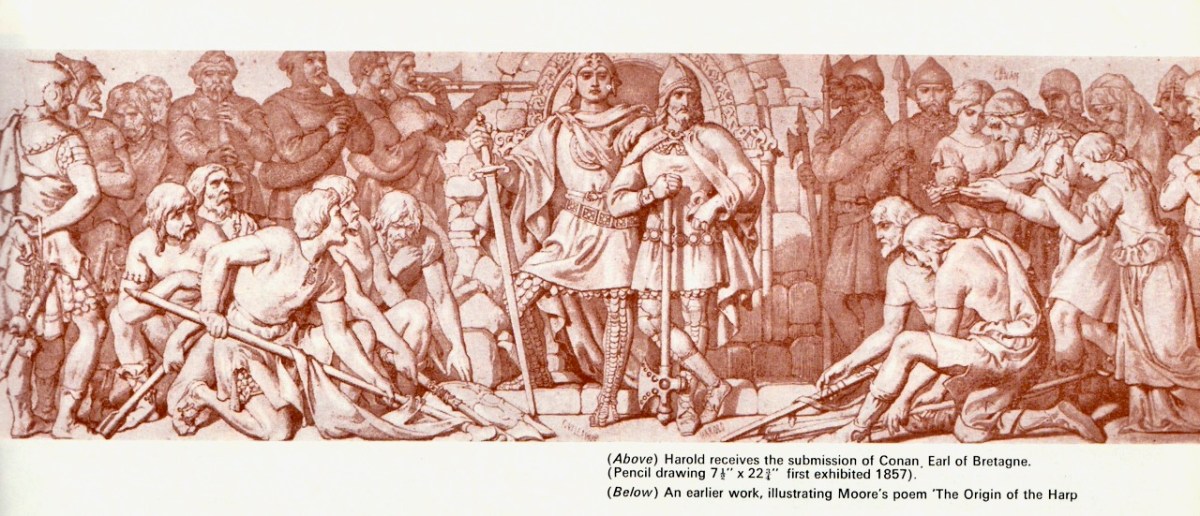

My header illustration is also from this article, in which John Turpin engagingly charts the ‘Celtic’ influences in the art of Daniel Maclise, who was born into poverty in Cork but who became one of the most successful painters of his generation. In Britain, Maclise is best known for the enormous murals he painted for the House of Lords. Of course, here in Ireland, he is the painter who has given us The Marriage of Aoife and Strongbow, and I have written about my own convictions as to his inspirations for the setting of that work.

July-August

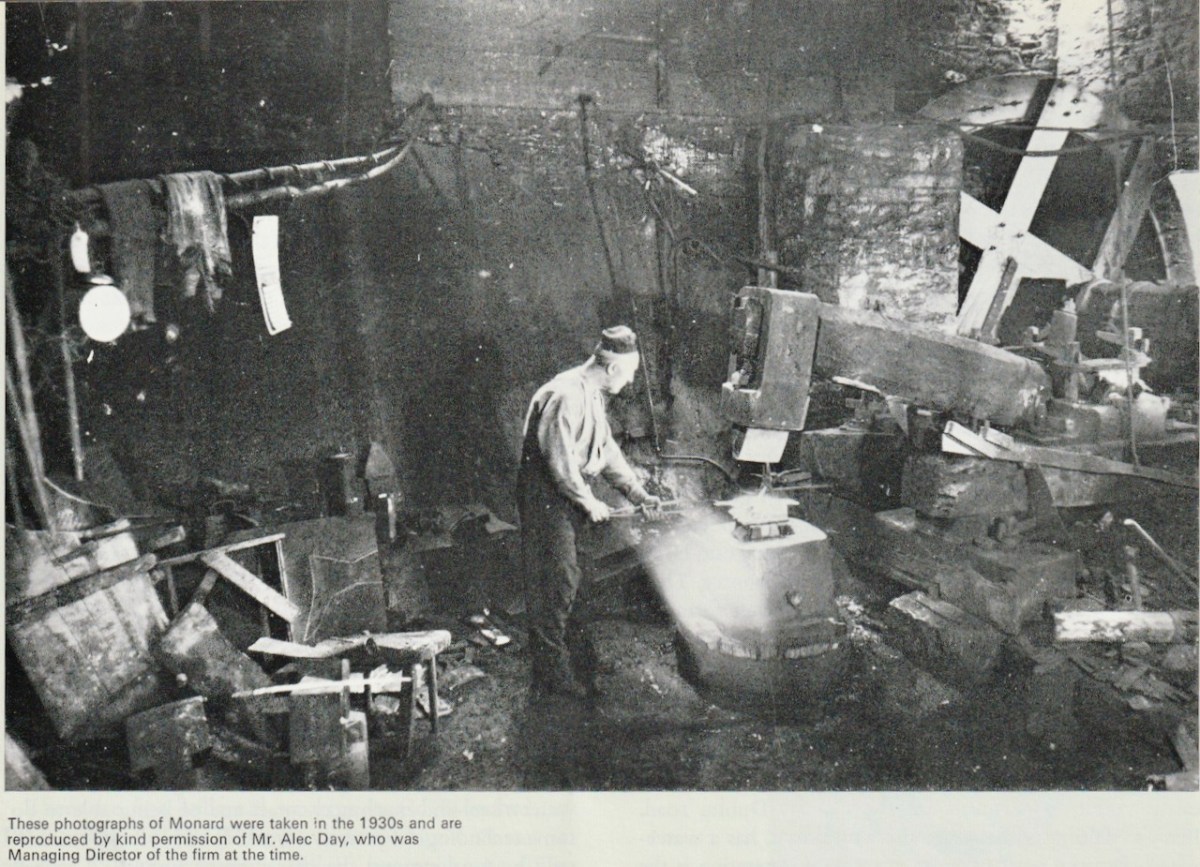

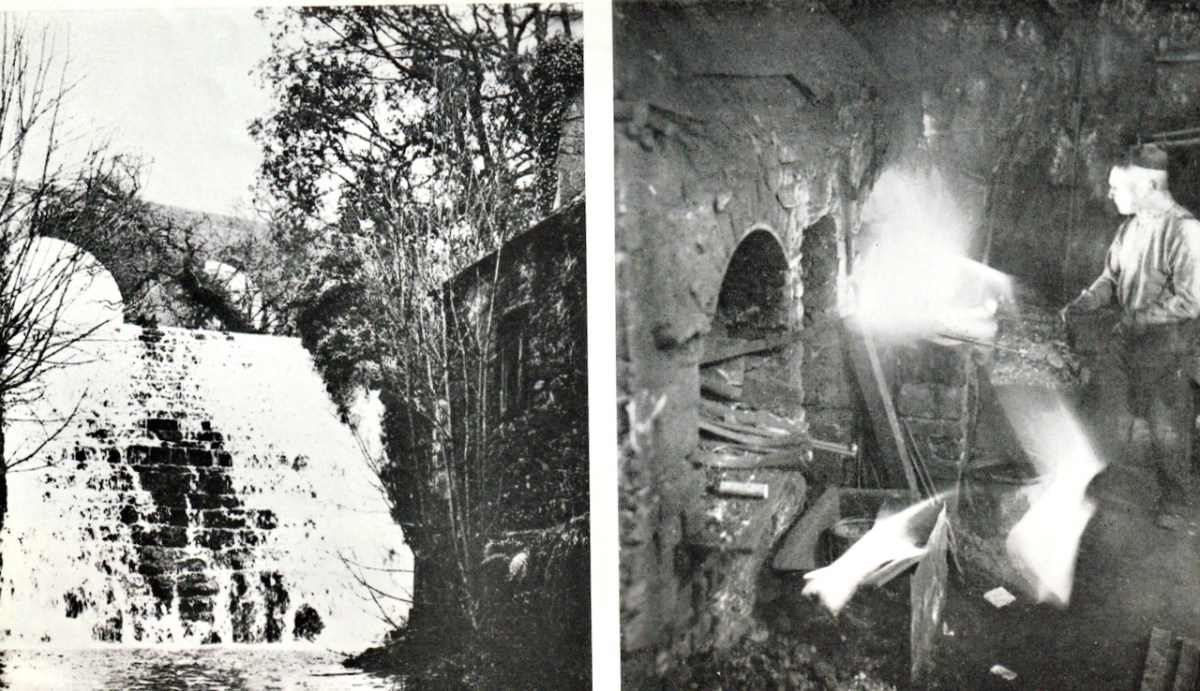

Ken Mawhinney has an article in this issue called The Waterwheel: Joy of the Industrial Archaeologist. He provides lists of where waterwheels are still to be seen but the one which resonated with me was the Monard Spade Mill. When we as students visited there around that time it was home to a pottery (Monard Glen – I bought coffee cups for my mother) but I remember being shown around by the knowledgeable people who were living there. Much of the original machinery was still in place.

September-October

The Bookshelf and Records page was a constant in the Ireland of the Welcomes at that time. I Must admit I was captivated by The Rajah from Tipperary! A little digging showed me that Hennessy’s book is still available – but so is George Thomas’s own account of his adventures! Can’t help lusting after the record selection on this page too.

November-December

Richard Condon, the American writer of thrillers, was living in Ireland in the 70s and indulging his gastronomic appetites by roving throughout the country visiting restaurants. Does anyone local to West Cork recognise this establishment? Here’s what Condon has to say about it:

And, of course, as confirmed to me by Jim O’Keeffe, it was what we all know as The Courtyard. The building is still there, with the iconic iron gates with the words O’Keeffe on them.

So there it is, a highly personal and idiosyncratic selections from Ireland of the Welcomes 51 years ago. I’ll try to catch up on 1973 before the year ends.