Ireland is ‘The Land of Saints’. The Catholic Online website lists 331 of them, but some get much better treatment than others. Last week we celebrated St Patrick – the news was full of it, as it always is on 17 March. Yet, just five days after Patrick’s Day – on 22 March – I was at a schoriacht and asked the assembled crowd who was the Saint for that day: nobody knew. It was the day for St Darerca and she is, unfairly, much neglected, especially since she is St Patrick’s sister. In order to redress the balance I have put together everything I can find on the story of St Darerca, and – because she has never been pictured (as far as I can tell) – I have illustrated it with some general Irish Saintly connections.

Land of the Saints: header picture – Clonmacnoise, Co Offaly – Ireland’s holy centre, and one of the oldest and most important early Christian settlements in Europe. Above – the beautifully located Kilmalkedar monastic site in Kerry has long associations with Saint Brendan the Navigator

St Darerca is first mentioned in the Vita tripartita Sancti Patricii (Tripartite Life of Saint Patrick), which some scholars believe was written in the sixth century – within a century of St Patrick’s death (possibly in 493 at the age of 120). In the Tripartite Life, we read that St Patrick had two sisters, and that when he came to Bredach in County Derry for an ordination, . . . he found there three deacons, who were sons of his sister Darerca . . . These deacons were eventually ordained bishops and became St Reat, St Nenn, and St Aedh, the . . . sons of Conis and Darerca, Patrick’s sister . . .

Upper – St Patrick’s Bell; lower – inscription on another 10th century bell – both now in the National Museum, Dublin

In his own Confessio, St Patrick makes no mention of his sisters. The Confessio begins:

. . . My name is Patrick. I am a sinner, a simple country person, and the least of all believers. I am looked down upon by many . . .

But it’s a very brief account of his life, and hardly qualifies as an autobioigraphy.

Medieval cross head, in the National Museum, Dublin

One version of the Tripartite Life suggests that both sisters were kidnapped from Britain along with St Patrick and returned to Ireland with him when he set out on his missions. A 17th century Irish hagiographer, John Colgan, collected fragments of information pertaining to Darerca . . . from Irish tradition . . . He asserted that St Darerca may have had as many as seventeen sons between two husbands, and that all of them became bishops. He also states that, according to tradition, many of these became saints:

. . . By Darerca’s first husband, Restitutus the Lombard, she bore St Sechnall of Dunshaughlin; St Nectan of Killunche, and of Fennor (near Slane); of St Auxilius of Killossey (near Naas, County Kildare); of St Diarmaid of Druim-corcortri, in addition to five other children. By her second husband Conis the Briton, she bore St Reat, St Nenn, and St Aedh; ancient Irish authors also attributed her motherhood to St Crummin of Lecua, St Miduu, St Carantoc, and St Maceaith . . .

A 1950s photograph from Tomás Ó Muircheartaigh showing the annual pilgrimage to the summit of St Patrick’s holy mountain in Co Mayo, Croagh Patrick

St Darerca’s second husband, Conis, was said by some to be the King of the Bretons, although others only suggest that, by him, she gave birth to Gradlon the Great, who became King of Brittany. It’s really surprising (and a shame) that we don’t know more about Darerca: perhaps she has just always been overshadowed by her famous brother. As well as – perhaps – seventeen sons, she is supposed to have had four daughters, all of whom were also connected with the spread of Christianity in Ireland. Only two are named: St Eiche of Kilglass and St Lalloc of Senlis.

The Ardagh Chalice, National Museum, Dublin

There is a reference to Darerca as having another name: Moninna, said to have founded a convent at Killeevy, Co Armagh which was second in importance only to that at Kildare. A curious story is told to account for the change of her name to Moninna. The Irish commentary is translated into English by Whitley Stokes:

. . . Darerca was her name at first. But a certain dumb poet fasted with her, and the first thing he said after being miraculously cured of his dumbness was minnin. Hence the nun was called Mo-ninde, and the poet himself Nine Ecis . . .

Moninna studied theology, established convents in Ireland, Scotland and England and travelled to Rome. Perhaps most interestingly she is also known by the name Liamain, and there is a connection with an ancient stone on the island of Inchagoill in Lough Corrib. The ‘Pillar Stone’ on that island is known as Lugnaedon Pillar, a piece of Silurian grit stone, about two feet high with an incised cross on the north side, and two such crosses on each of the other sides. The inscription on the stone translates as . . . The stone of Lugnaedon, son of Limenueh . . . or Liamain. The pillar is said to originate in the 6th century, and would therefore be the oldest Christian inscribed stone in Ireland.

Two photographs of the 6th century Lugnaedon Pillar on Inchagoill Island. It is also known as the Rudder Stone because of its shape

The Benedictines say that Darerca’s name is derived from the Irish Diar-Sheare which means ‘constant and firm love’. And, finally, a piece of local folklore say that St Darerca blessed a poor man’s beer barrel so that it provided an endless supply of beer ever after!

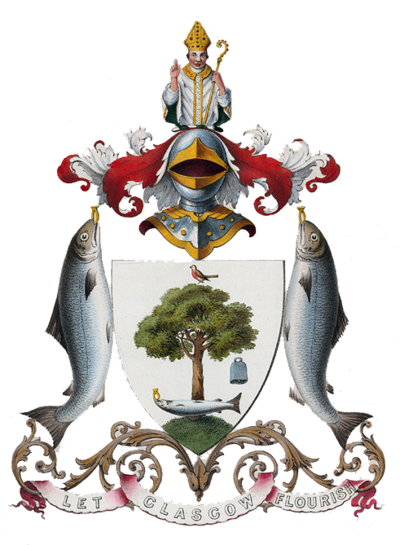

Lives of the Saints – a detail from a stained glass window by George Walsh in St Kentigern’s Church, Eyries

So there you have it – scraps gleaned from many sources, some of which are not named – from which we can piece together an incomplete picture of an Irish saint who may well have done as much in her day for Christianity in Ireland as her famed brother. How about giving Patrick a rest next year and, instead, celebrating the day of St Darerca?

Email link is under 'more' button.