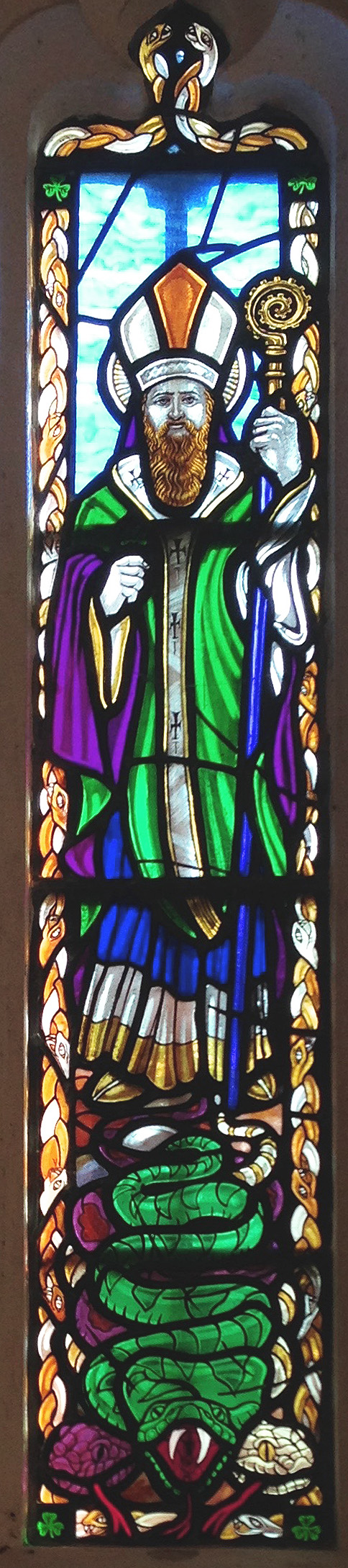

Our travels have taken us to quite a few Christian pilgrimage sites in Ireland: they are all fascinating, and range from St Patrick’s holy mountain – Croagh Patrick (where snakes were cast out of this country forever) – through the rather daunting Station Island on Lough Derg (where a medieval pilgrim entered, and returned from, Purgatory) to the more ‘unofficial’ shrine at Ballinspittle, here in West Cork, where a statue of the Virgin was seen to move (by hundreds of onlookers) in 1985. Recently we found ourselves in Mayo, so a trip to Ireland’s most impressive shrine – at Knock – was essential.

These illustrations show the evolution of the shrine. At the header is the updated interior of the Parish Church of Knock-Aghamore today, showing the beautiful high altar which was made by P J Scannell of Cork and which was presented as a gift during a pilgrimage in 1880. Behind this east wall is the gable where, on 1st August 1879, fifteen local people witnessed an apparition of Mary, Joseph, St John the Evangelist, and a lamb on an altar which seemed to float, stationary and silent, in front of the wall. It was 8pm and the rain was pouring down, yet the gable wall and the ground in front of it remained dry. The vision – which was also seen by others – seemed to last for about two hours. The upper picture above, which probably dates from around 1880, shows the gable and in front of it a rack of crutches and other paraphernalia apparently left by those cured at the shrine. The very first recorded cure, which happened soon after the vision, was of Delia Gordon, a young girl from nearby Claremorris, who was instantly cured of an acute ear infection and deafness after her mother scraped a little of the plaster off the gable wall and placed it into her ear. You can see in the upper picture where considerable amounts of the plaster appear to have been removed (presumably, following that first cure); by the 1930s (second picture) an iron fence had been erected to protect the wall. In 1963 (third picture), a dedicated chapel had been built in front of the gable, and today (fourth picture) a modern Apparition Chapel is in place to contain the large number of pilgrims who attend mass there on a daily basis. You can also see the elegant sculptures which have been installed on the wall to represent the figures of the apparition.

The vision is superbly depicted in this enormous mosaic which has recently been installed in the Basilica at Knock. P J Lynch, the artist who designed the mosaic, said he . . . tried hard to capture the sense of the wonder that the witnesses must have felt on that wet August evening back in 1879 . . . The mosaic measures 14 metres square and is one of the largest single flat pieces of religious mosaic of its kind in Europe: it is made predominantly from Venetian glass smalti and there are approximately 1.5 million individual pieces of mosaic in the complete work.

This is original stonework from the gable wall to the Parish Church: the lower picture is a panel built in to the modern Apparition Chapel wall. The statements made by the 15 witnesses who saw the vision at the wall in 1879 are fully documented here – an official Commission of Enquiry was held by the Catholic Church in that same year and concluded . . . the words of the witnesses were trustworthy and satisfactory . . . a further investigation in 1936 interviewed the then surviving witnesses, who corroborated what they had seen. Mary Byrne, who was 29 at the time of the apparition and 86 during the second enquiry said . . . I am clear about everything I have said and I make this statement knowing I am going before my God . . . She died shortly afterwards. John Curry, the youngest witness, was 5 in 1879. The child said . . . he saw images, beautiful images, the Blessed Virgin and St Joseph. He could state no more than that he saw the fine images and the light, and heard the people talk of them, and stood upon the wall to see them . . . He confirmed his memories when interviewed in new York for the 1936 enquiry.

Over a million people a year come to Knock, in search of faith, enlightenment, cures perhaps: or just out of curiosity. It is a place with a great sense of purpose – and long may it continue. As a (now retired) church architect I was distinctly struck by the enormous Basilica which was constructed initially in the 1970s and which has been refurbished very recently. It is spectacular in its size and scale and is fittingly furnished with powerful works of art. In particular I was impressed by the large, harrowing, painted Stations of the Cross: unfortunately – and strangely – I can find no record anywhere of the artist.

If you have a spare couple of hours it’s worth finding and watching this entertaining and fair-minded documentary about Knock, made by RTÉ in 2016:

I make no judgments as to the veracity or otherwise of what was witnessed on that day in 1879. There have been many theories put forward, ranging from magic lanterns to unrest provoked by the Land Acts! But why should we doubt the faith of anyone, whatever their religion? The Christian story is all about miracles, so surely miracles are just as possible in the 19th century as they were in the 1st… The village of Knock carries on its normal life around all the trappings of the shrine: shops selling statues and Holy Water bottles abound, and add to the colour. On the site you can look out the well-curated museum, and treat yourself to good refreshments. It’s all worth visiting, even if your interest is purely anthropological. The Pope himself will be there this August and all the 45,000 (free) tickets have been booked. If the sun keeps on shining – and perhaps it will – it’ll be a grand day for all!