Patrick lights the Paschal Fire on the Hill of Slane. Richard King window, Church of St Peter and Paul, Athlone

A joint post – text by Robert, images by Finola

Last week we talked about Ireland’s very first saint – Ciarán (or Piran), who was born on Cape Clear. His aim in life was to convert the heathen Irish to Christianity, but they were having none of it: they tied him to a millstone and hoisted him over the edge of a cliff. Fortunately – and miraculously – the wondrous millstone floated him over to Cornwall where he became their Patron Saint and is celebrated with great acclaim on March 5th every year.

A typical representation of Patrick, older and bearded, in bishop’s robe, holding a shamrock in one hand and a crozier on the other. Skibbereen Cathedral

To return the favour of gaining an important saint from Ireland, the British have given Ireland their special saint – Patrick – and he is being celebrated this week in similar fashion. So here’s the story of Saint Patrick, seen through the eyes of an Englishman (albeit one with Cornish connections) and illustrated by Finola with a series of images from her collection.

Still traditional – looking fierce – but this one has beautiful detailing, including the interlacing surrounding the cherubs. St Carthage Cathedral, Lismore

Of course, there’s the real Patrick – the one we know through his own Confessio. The best summary we’ve come across of what can be deduced from the historical documents is the audio book Six Years a Slave, which can be downloaded from Abarta Heritage, and which is highly recommended (be warned – no snakes!). But what you’re going to get from me today is the good old-fashioned Patrick, with all his glamour and colour and centuries of accrued stories – just as he’s shown in Finola’s images.

Six Years a Slave – this Harry Clarke window in the Church of The Assumption, Tullamore, seems to depict Patrick tending sheep during the period of his captivity

Patrick was born and brought up somewhere in the north west of Britain. He was of Romano British descent: his father was a a decurion, one of the ‘long-suffering, overtaxed rural gentry of the provinces’, and his grandfather was a priest – the family was, therefore, Christian. In his own writings Patrick describes himself as rustic, simple and unlearnèd. When still a boy, Patrick was captured by Irish pirates and taken to be a slave in Ireland. He was put to work on a farm somewhere in the west and spent the long, lonely hours out in the fields thinking about the Christian stories and principles he had been taught back home.

Patrick is visited by a vision – the people of Ireland are calling to him to come back and bring Christianity to him. Richard King window, Church of St Peter and Paul, Athlone. Read more about Richard King and the Athlone windows in Discovering Richard King

After six years he escaped from his bondage and made his way back to Britain – apparently by hitching a lift on a fishing boat. Because he had thought so much about Christianity during those years away, he decided to become a bishop which, after a few years of application, he did. Although he had hated his enforced capture he was aware that Ireland – as the most westerly outpost of any kind of civilisation – was one of the only places in the known world that remained ‘heathen’, and he was nagged by his conscience to become a missionary there and make it his life’s work to convert every Irish pagan.

Detail from Patrick window by Harry Clarke in Ballinasloe

When you see Patrick depicted in religious imagery he always looks serious and, perhaps, severe. You can’t imagine him playing the fiddle in a session or dancing a wild jig at the crossroads. In fact he was well know for his long sermons: on one occasion he stuck his wooden crozier into the ground while he was preaching and, by the time he had finished, it had taken root and sprouted into a tree!

Patrick with his hand raised in a blessing, accompanied by his symbols of the Paschal Fire and the shamrock. Harry Clarke Studio window, Bantry

Perhaps it was his severity that caused him to be respected: while giving another sermon (at the Rock of Cashel) he accidentally and unwittingly put the point of his crozier through the foot of the King of Munster. The King waited patiently until Patrick had finished sermonising then asked if it could be removed. Patrick was horrified at what he’d done, but the King said he’d assumed it was all part of the initiation ritual!

In Richard King’s enormous Patrick window in Athlone, the saint is depicted as youthful and clean-shaven. Here he is using the shamrock to illustrate the concept of the Trinity

Patrick first landed on the shores of Ireland just before Easter in 432 AD and established himself on the Hill of Slane – close to the residence of the High King. In those days the rule was that only the King himself was to light the Bealtaine Fire to celebrate the spring festival, but Patrick pre-empted this by lighting his own Paschal Fire on the top of the hill, thus establishing his authority over that of the High King (see the first image in this post). Somehow, he got away with it – and the fire has been lit on the top of the Hill of Slane every Easter from that day to this.

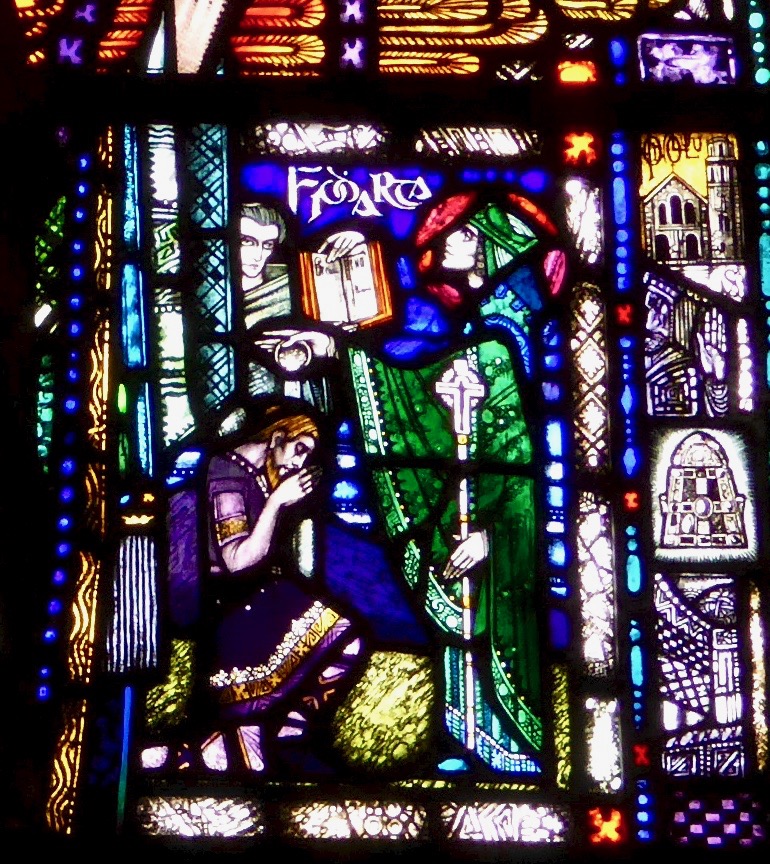

Another panel from the Richard King window – Eithne and Fidelma receive communion from Patrick. They were daughters of the King of Connaught; Eithne was fair-haired and Fidelma a redhead, and they were baptized at the Well of Clebach beside Cruachan

St Patrick seems to have been everywhere in Ireland: there are Patrick’s Wells, Patrick’s Chairs (one of which in Co Mayo – the Boheh Stone – displays some fine examples of Rock Art), Patrick’s Beds and – on an island in Lough Dergh – a Patrick’s Cave (or ‘Purgatory’) where Jesus showed the saint a vision of the punishments of hell.

Patrick blesses St Mainchin of Limerick. Detail from the Mainchin window in the Honan Chapel, by Catherine O’Brien for An Túr Gloinne

The place which has the most significant associations with Patrick, perhaps, is Croagh Patrick – the Holy Mountain in County Mayo, on the summit of which the saint spent 40 days and 40 nights fasting and praying, before casting all the snakes out of Ireland from the top of the hill – an impressive feat. To this day, of course, there are no snakes in Ireland – or are there? See my post Snakes Alive for musings on this topic (it includes a most impressive window from Glastonbury!)

Like many Patrick windows, this one, By Harry Clarke in Tullamore, shows Patrick banishing the snakes. This one has all the gorgeous detailing we expect from Clarke, including bejewelled snakes

When Patrick considered that he’d finished his task, and the people of Ireland were successfully and completely converted, he returned to Britain and spent his retirement in the Abbey of Glastonbury – there’s a beautiful little chapel there dedicated to him.

This depiction of Patrick on the wall of his Glastonbury chapel shows him with familiar symbols but also several unusual symbols – an Irish wolfhound, high crosses, and Croagh Patrick, the holy mountain

It’s logical he should have chosen that spot to end his days as it must be the most blessed piece of ground in these islands, having been walked upon by Jesus himself who was taken there as a boy by his tin-trading uncle, Joseph of Arimathea. St Bridget joined Patrick there in retirement and they are both buried in the Abbey grounds, along with the BVM who had preceded them to that place a few centuries earlier.

From the George Walsh window in Eyeries, Patrick returns to convert the Irish

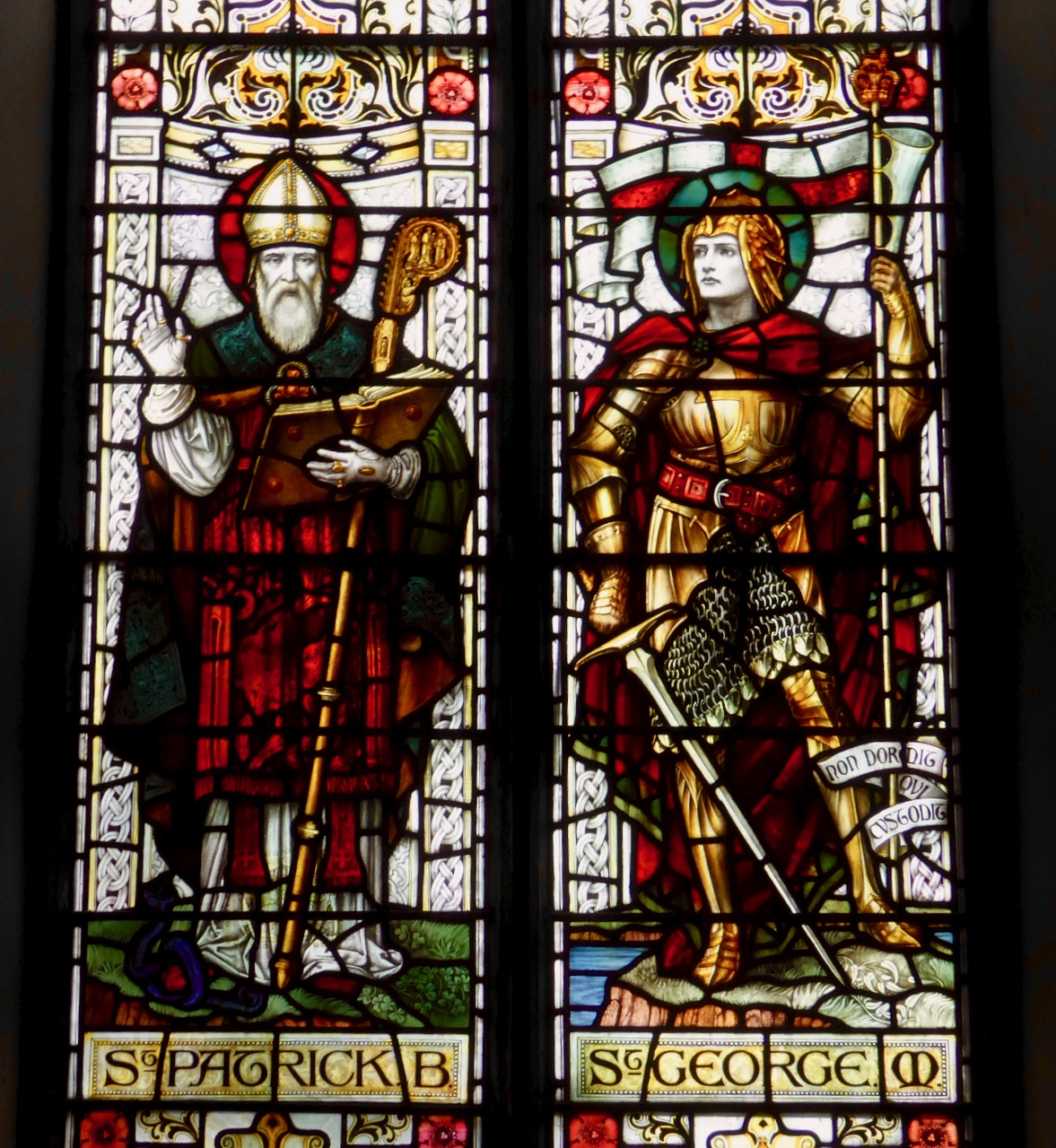

A depiction of Patrick below comes from St Barrahane’s Church of Ireland in Castletownsend where he is shown alongside St George. The window dates from before Irish independence and is an attempt to show the unity of Britain and Ireland through their respective patron saints. Perhaps meant to represent friendship between the countries, nevertheless nowadays it seems to display a colonial overtone that is an uncomfortable echo of past mores.

The window is by Powells of London and dates to 1906

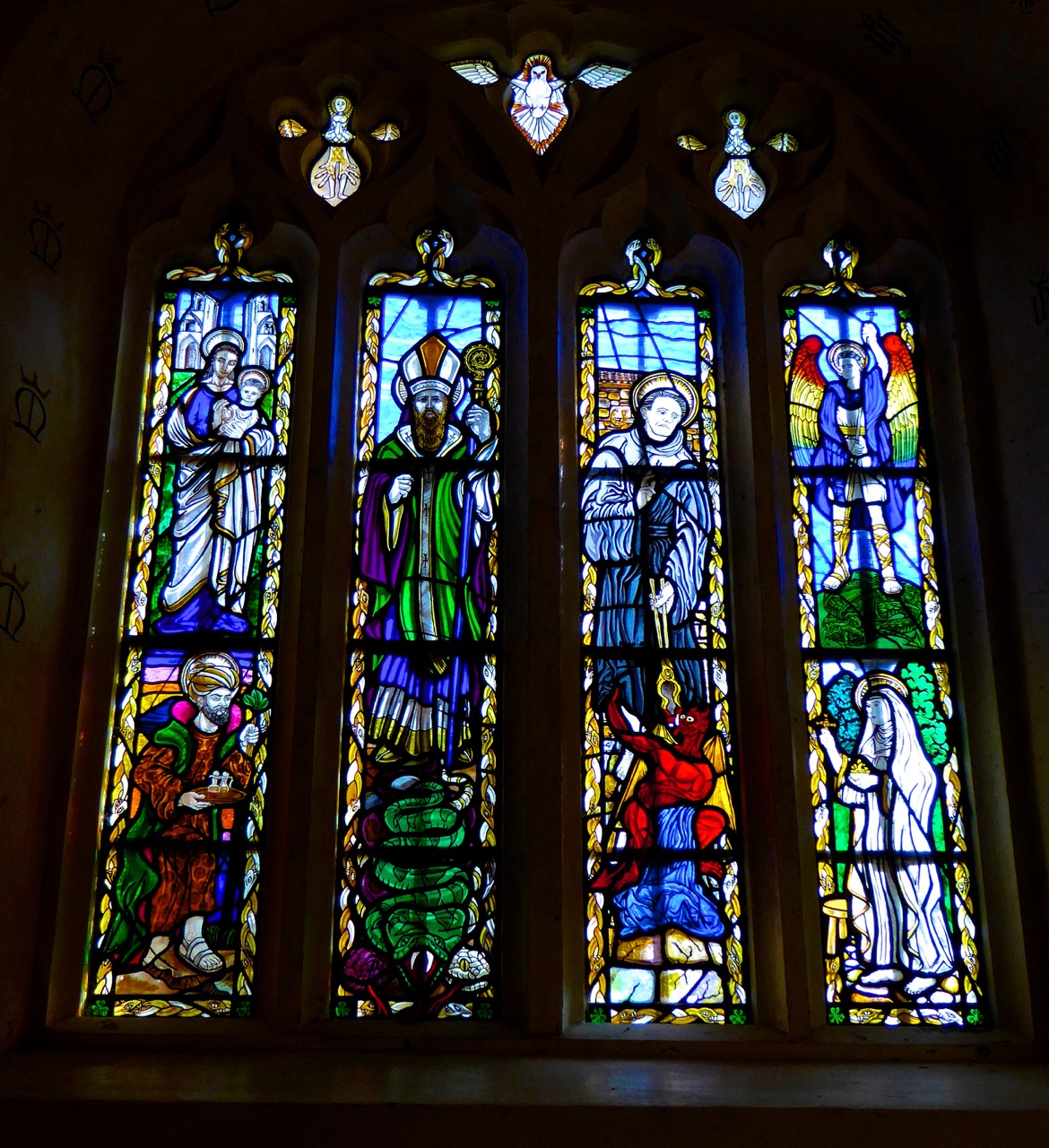

So let’s leave Patrick doing what he came back to do – a last panel from the Richard King window in Athlone shows him performing his saintly task of converting the Irish – one chieftain at a time.