It’s an archaeologist’s job to dig things up from the past. Today – the Feast of St Patrick – I’m digging up an old custom and suggesting that it’s something we should all revive!

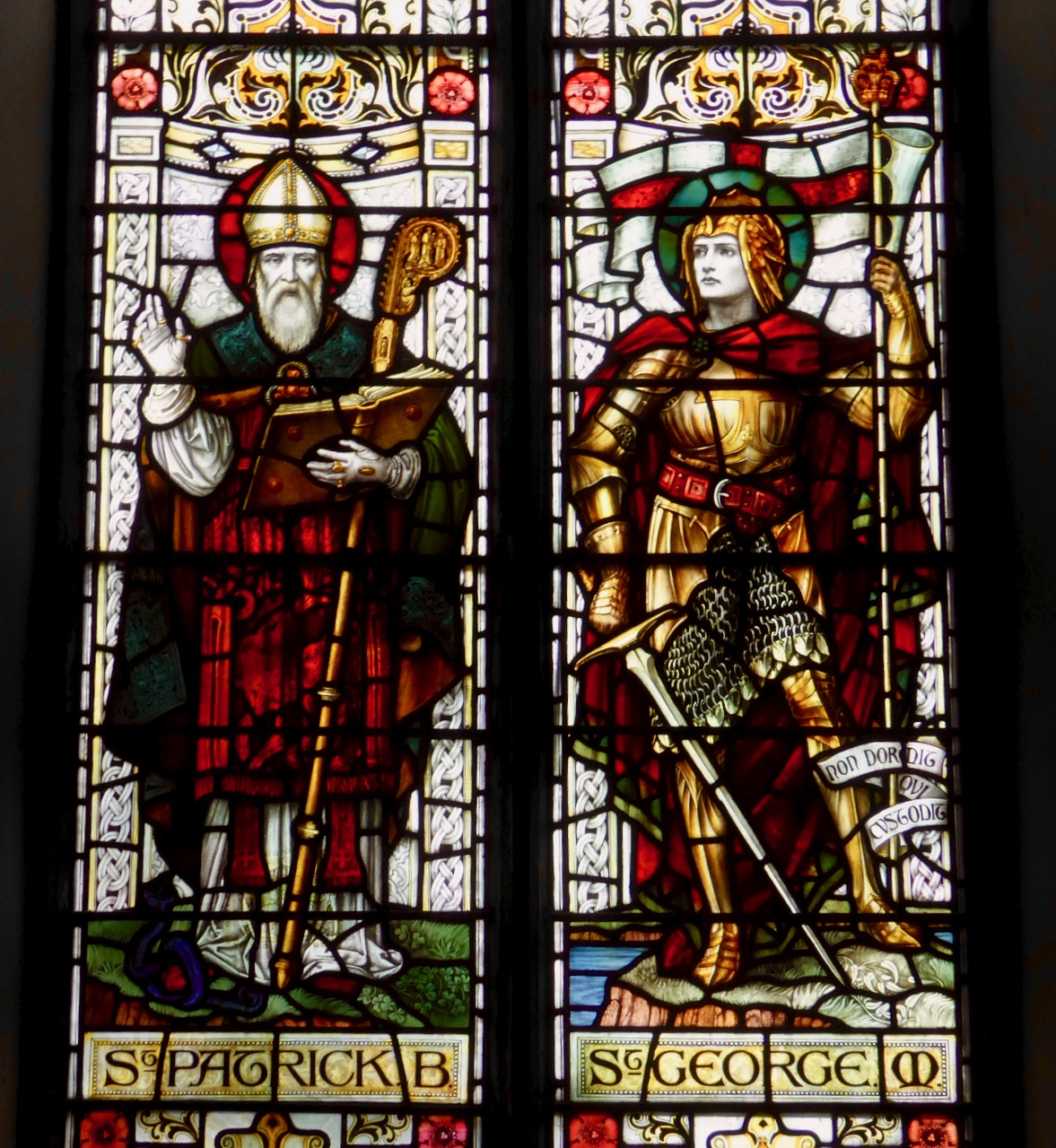

Examples of St Patrick’s crosses survive in glass cases today. These three are from Ireland’s National Museum of Country Life, Castlebar, Co Mayo

I have found much of my information on this subject in Kevin Danaher’s 1972 book The Year in Ireland – A Calendar published by The Mercier Press. Danaher begins his calendar on St Brighid’s Day (his spelling), and naturally discusses the custom of the making of bogha Bríde – the St Brighid’s cross. In this tradition, very much alive today, a cross is made from straw or reed and hung in the house to ensure good luck and protection for the coming year. In future years new crosses are made, but the old ones are never thrown away: if you visit a traditional Irish cottage, you are likely to see a whole lot of Brighid’s crosses pinned over the mantlepiece or among the rafters in various stages of decay.

A traditional Irish cottage, Finola and her St Brighid’s cross. See this post

When Danagher comes to the next important Irish Festival – St Patrick’s Day – he mentions a similar custom involving a St Patrick’s cross or badge, worn on the clothing for the day itself, and then hung in the house to ensure that the saint’s blessing continues through the years. The custom was still within living memory when Danaher wrote, but its practice appears to have died out altogether in the early years of the twentieth century, although surviving examples of these crosses, emblems or badges can be seen in museums today. I am not aware of anyone keeping up this custom so – to celebrate the day that’s in it – I am proposing a revival!

Danaher’s illustrations of St Patrick’s crosses from The Year in Ireland

First, the history: an English traveller in Ireland, Thomas Dinely, wrote in 1681:

The 17th day of March yearly is St Patrick’s, an immoveable feast when the Irish of all stations and conditions wore crosses in their hats, some of pins, some of green ribbon, and the vulgar superstitiously wear shamroges, 3-leaved grass, which they likewise eat (they say) to cause a sweet breath . . .

Dean Swift in his Journal to Stella wrote from London on 17 March 1713:

The Irish folks were disappointed that the Parliament did not meet to-day, because it was St Patrick’s day; and the mall was so full of crosses, that I thought all the world was Irish . . .

Here’s ‘Mannanaan Mac Lir’ writing in the Journal of the Cork Historical Society in 1895:

For a week or so preceding the National Festival, the grown members of the family are occupied in making “St Patrick’s Crosses” for the youngsters, boys and girls; because each sex have a radically different “Cross”. The “St Patrick’s Cross” for boys consists of a small sheet of white paper, about three inches square, on which is inscribed a circle which is divided by elliptical lines or radii, and the spaces thus formed are filled in with different hues, thus forming a circle of many coloured compartments. Another form of St Patrick’s Cross is obtained by drawing a still smaller circle, and then six other circles, which have points in the circumference of this circle as their centre, and its centre as their circumferential point, are added; after which one large outer circle encompasses the whole, thus forming a simple and not inartistic attempt at imitating those circle or bosses of our beautiful Celtic cross pattern. The many spaces, concave, convex or otherwise, thus formed, are then shaded in; each a different hue, and this constitutes the “St Patrick’s Day Cross”, of which our little ones are so proud. In our time, when every school boy is supplied with a pair of compasses and a box of water colours, the making of a St Patrick’s Cross is only the work of a few idle moments . . .

Hmmm… Well, the architect in me is intrigued enough to try out these instructions and – perhaps – add a few embellishments to see what sort of a job can be made of it:

What do you think? I have to admit to using my electronic drawing board rather than the compasses and water colours! ‘Mannanaan Mac Lir’ goes on to describe the girl’s cross:

The little girl’s “St Patrick’s Day Cross” – which is made by an elder sister, or if sufficiently skilled, by herself – is formed of two pieces of card-board or strong thick paper, about three inches long, which are placed across at right angles, forming a cross humette. These are wrapped or covered with silk or ribbon of different colours, and a bunch or rosette of green silk in the centre completes the tasteful little girl’s “St Patrick’s Cross”, which is pinned on the bosom or shoulder . . .

Not a little curious is the etiquette of those children’s “St Patrick’s Crosses,” for whereas it would be considered effeminate of a little boy to wear “a girl’s cross”, it would be considered most unbecoming on the part of the little miss to don a boy’s paper cross . . .

‘Mannanaan Mac Lir’ continues to enlighten us further on this custom:

I have known two or three old priests in Cloyne diocese break up and distribute among the girls of their respective parishes their old and worn vestments, for the purpose of being made into St Patrick’s crosses. The cross thus made (from a priest’s vestment) was an object of veneration; and I have known many such forwarded by their owners to their kindred in America, where they were doubtless received as welcome souvenirs of an ancient custom in the land of their fathers . . .

My final offering (above) – have I encouraged you all to get busy and help me revive this custom in time for St Patrick’s Day next year? I hope so . . . I’ll finish off with a couple of pics of a custom that’s still as strong as ever: the annual St Patrick’s Day Parade in Ballydehob, West Cork. Of course, the sun shone out!