If you’ve read my series Saints and Soupers, you might remember the character who appears in Part 6, Father John James Murphy – The Black Eagle of the North. That’s him, below. It’s always been my intention to revisit him at some point, specifically to try to investigate that amazing nickname. It’s only taken me 6 years.

First of all, let me tell you why now, and then the deeply personal reason why I want to write more about Fr Murphy. Why now? I have just been loaned a copy of Father John Murphy: Famine Priest by AJ Reilly, published in 1963 by Clonmore and Reynolds – my sincere thanks to Jennifer Pyburn of Schull for the loan, and Dan Allen of Goleen for conveying it to me. An aside – the Clonmore in the publisher’s title is from Lord Clonmore, later 8th Earl of Wicklow, who together with his partner Reynolds (about whom I can discover nothing) founded the only serious Catholic publishing company in Ireland in the first part of the 20th century. Apparently, when Clonmore was a boy, he used to attend the servants’ mass on Sunday morning and later converted to Catholicism, which horrified his Church of Ireland Anglo-Irish family. His father disinherited him, but he nevertheless succeed to the title in 1946. His father, by the way, was the Earl of Wicklow I wrote about in my post Ecce Homo: Harry Clarke’s Kilbride Window

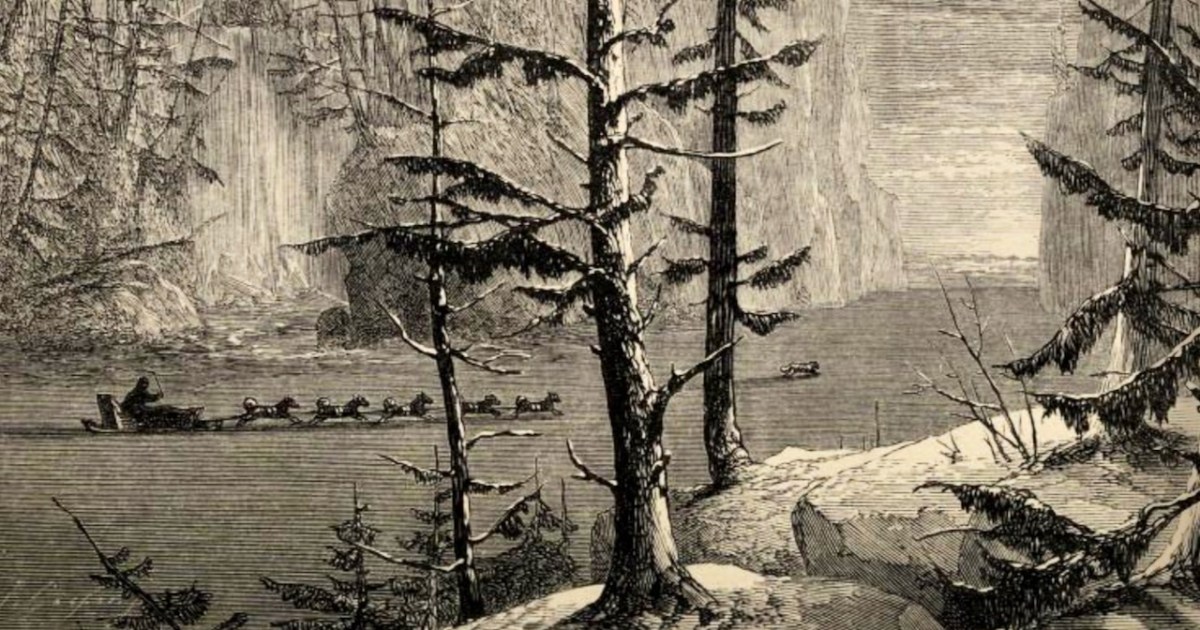

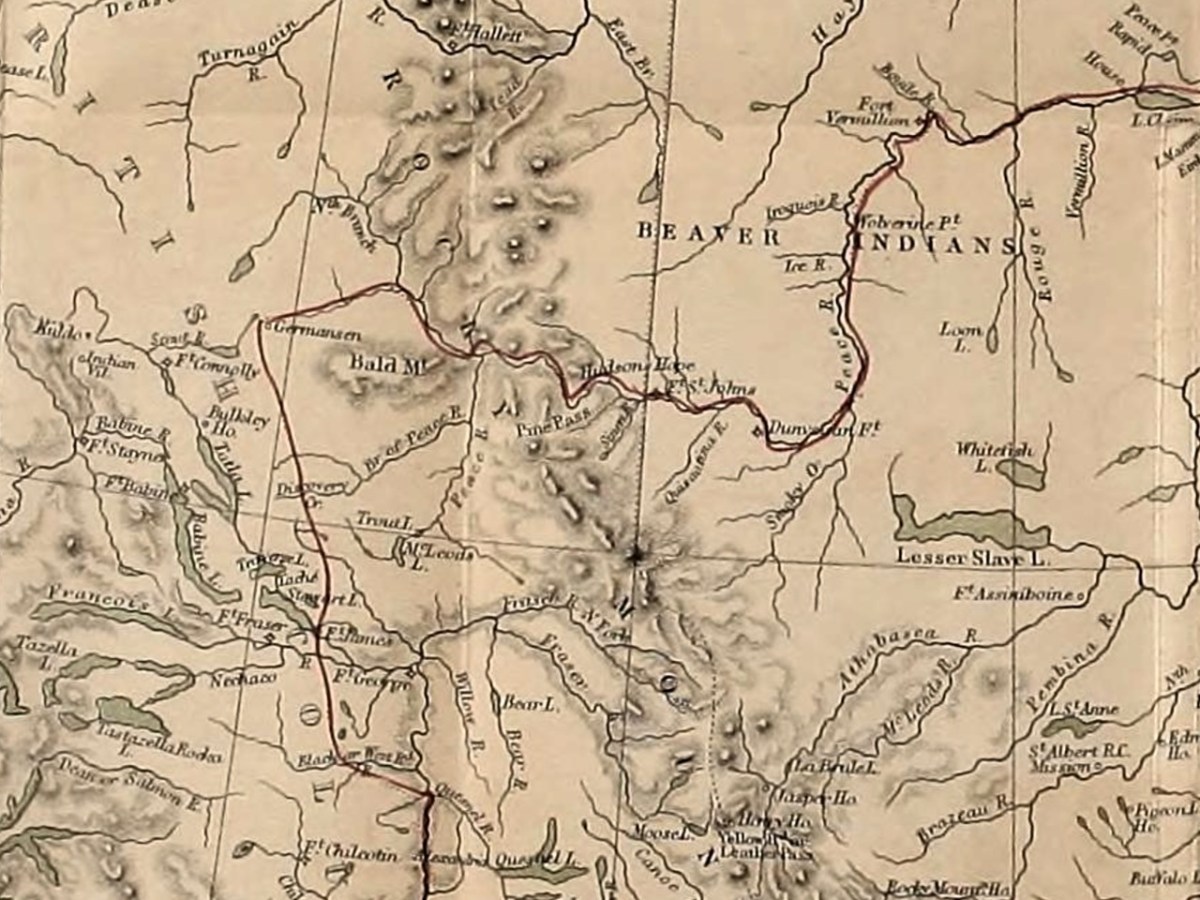

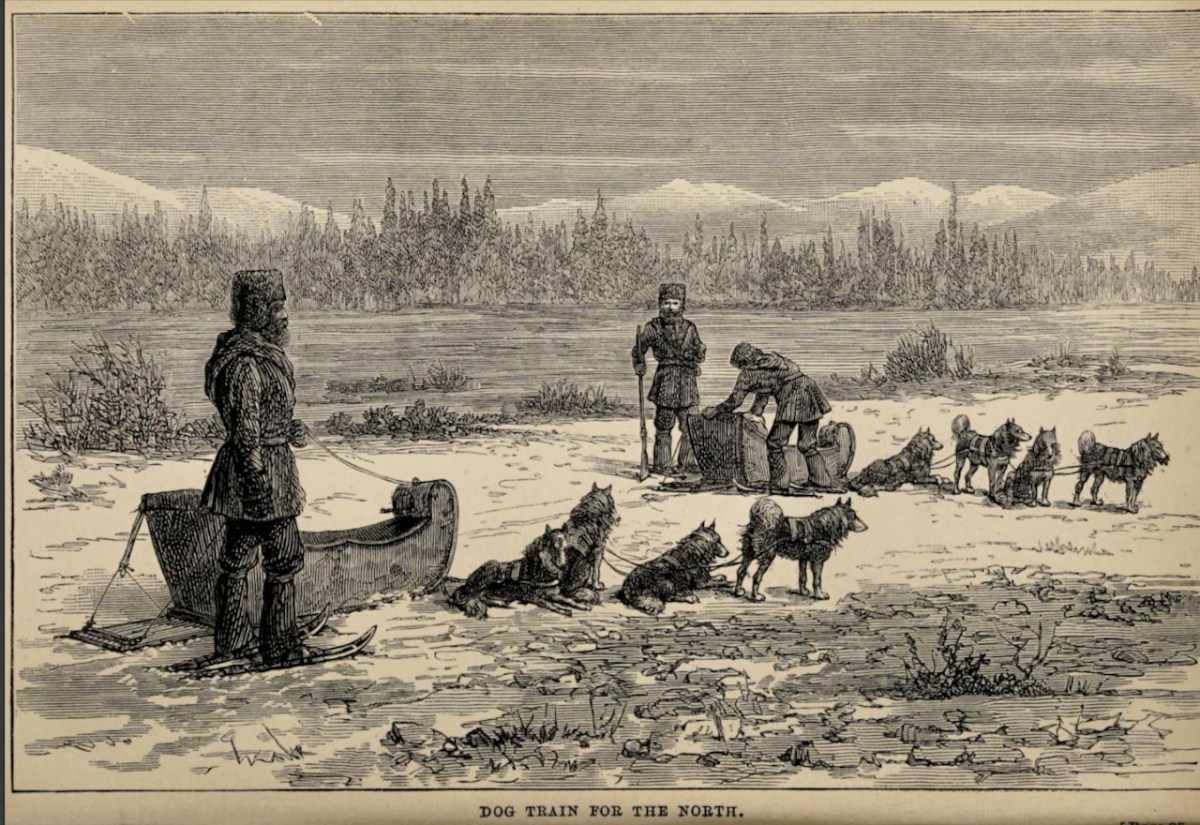

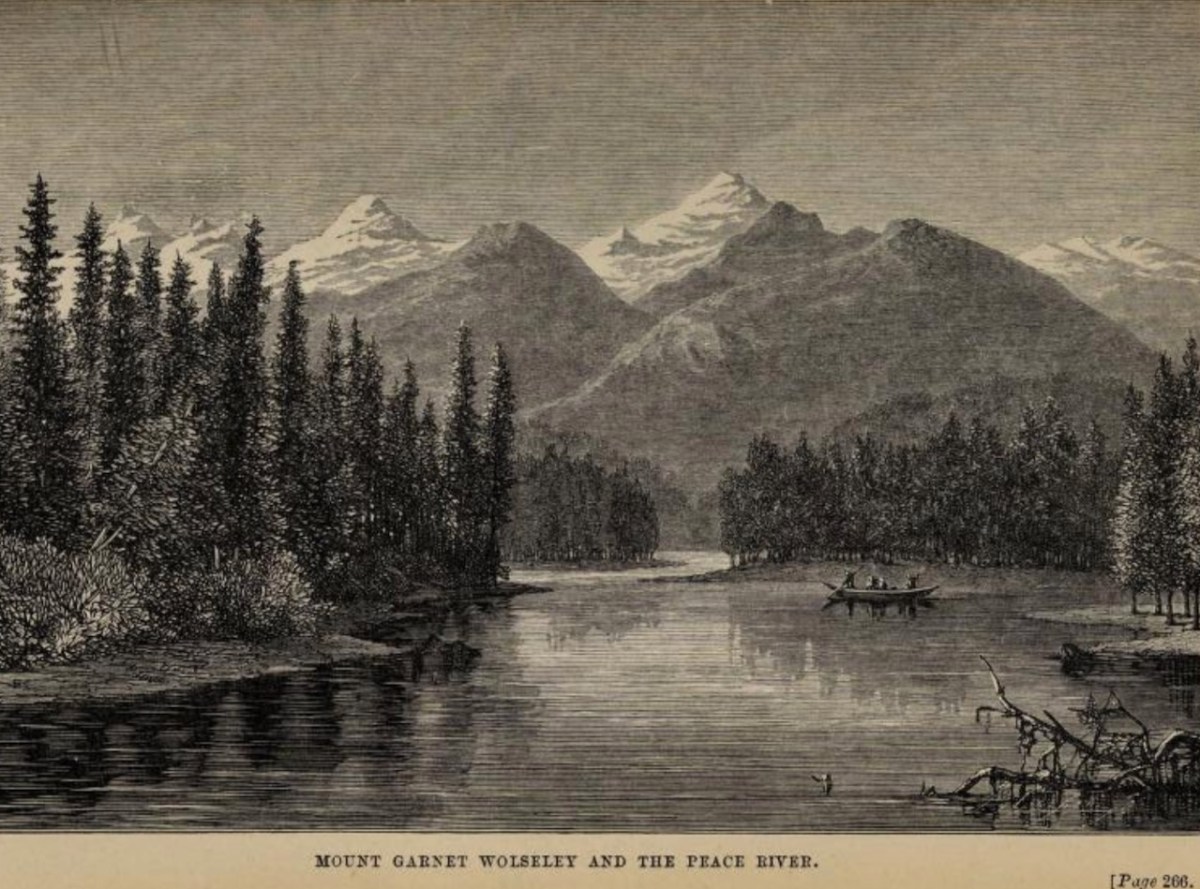

And the personal reason? Reading about Fr Murphy transported me back to my own fur trade days! From 1974 to 1978 I was enrolled in a doctoral program in Archaeology at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver. My research and projects were centred on the excavation of fur trade forts along the Peace River (above), in northern British Columbia, built and occupied between 1793 and 1823, when they were shut down as a result of a massacre. For several summers I camped on the fort sites and dug what was left after 150 years of abandonment. I also spent time in the Hudson’s Bay Co Archives in Winnipeg, piecing together from the original manuscript journals what had happened in those forts. So when I read about Fr Murphy and his time in the Hudson Bay company, some of it is so familiar. Some of it, of course, is pure speculation – something that is readily admitted by Reilly.

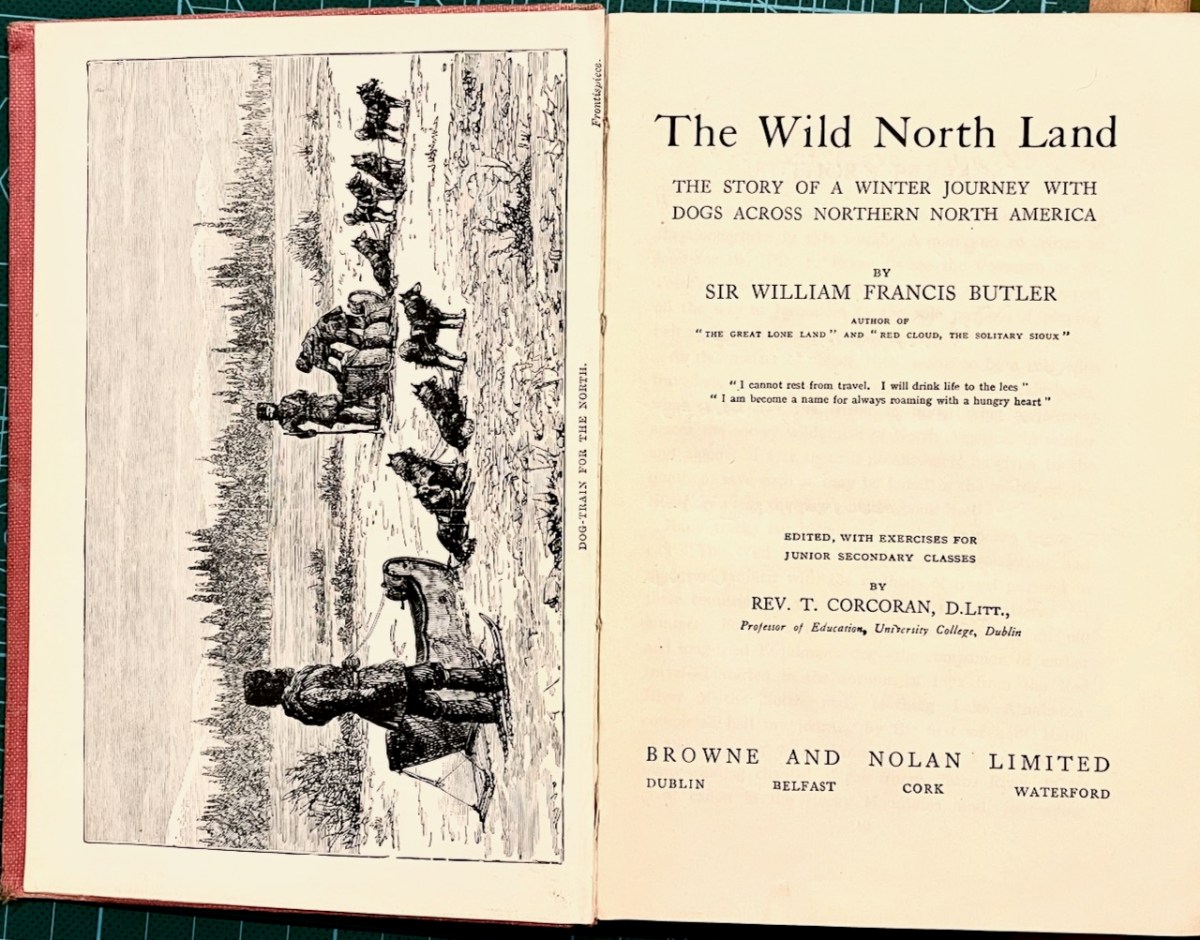

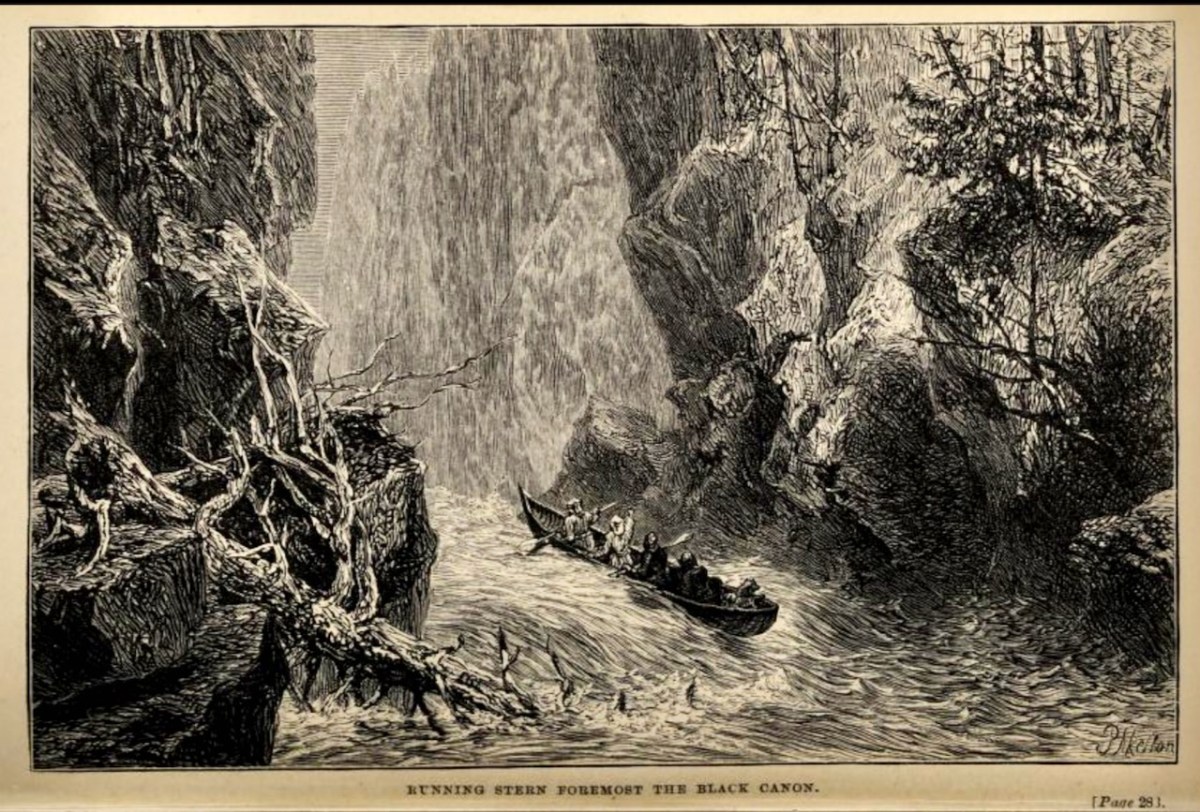

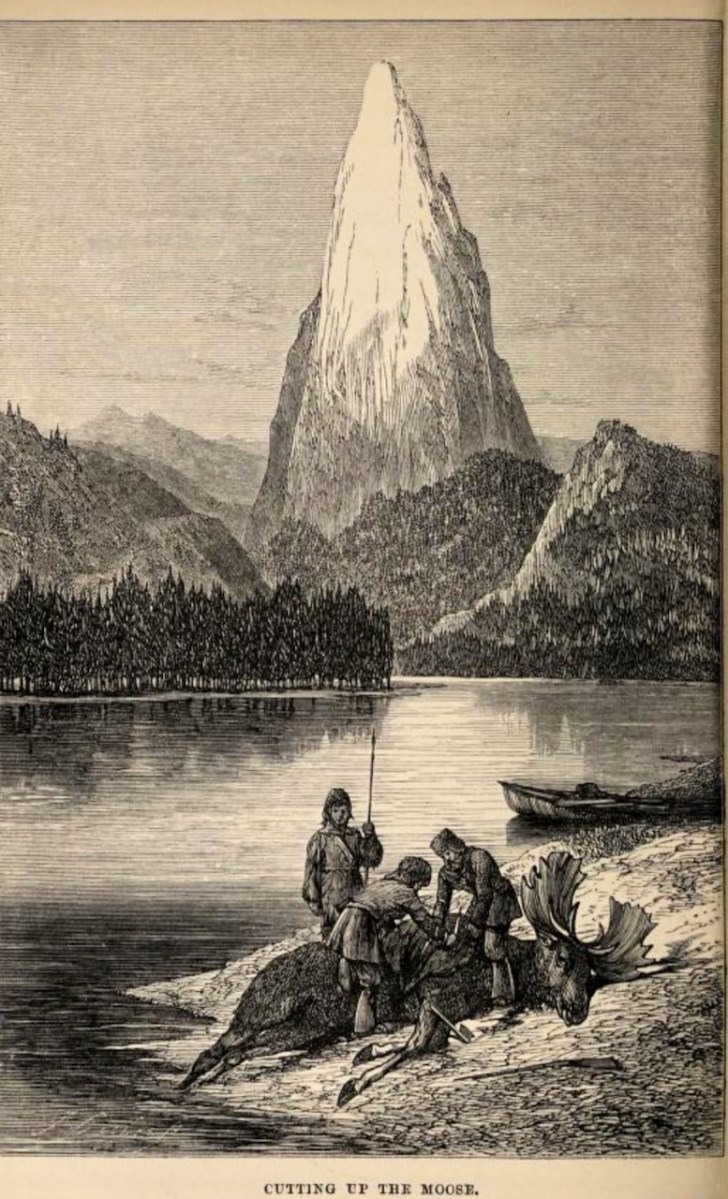

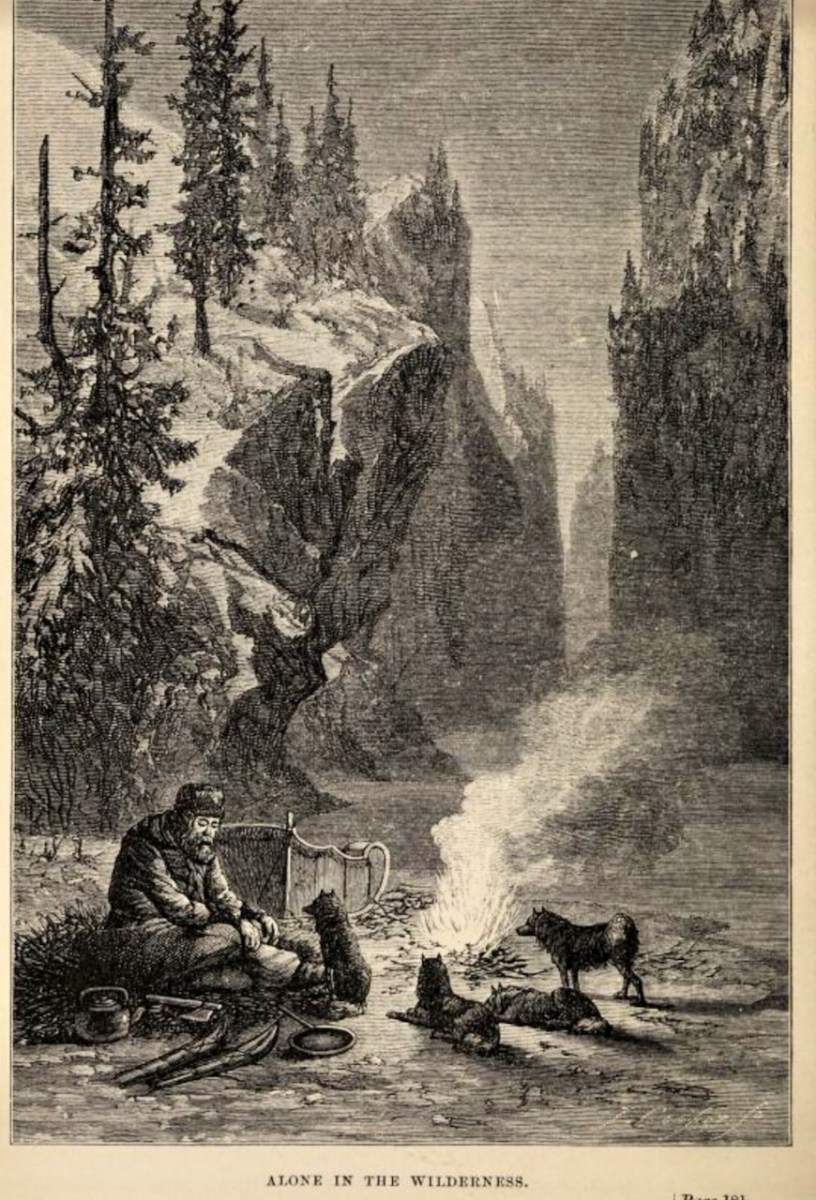

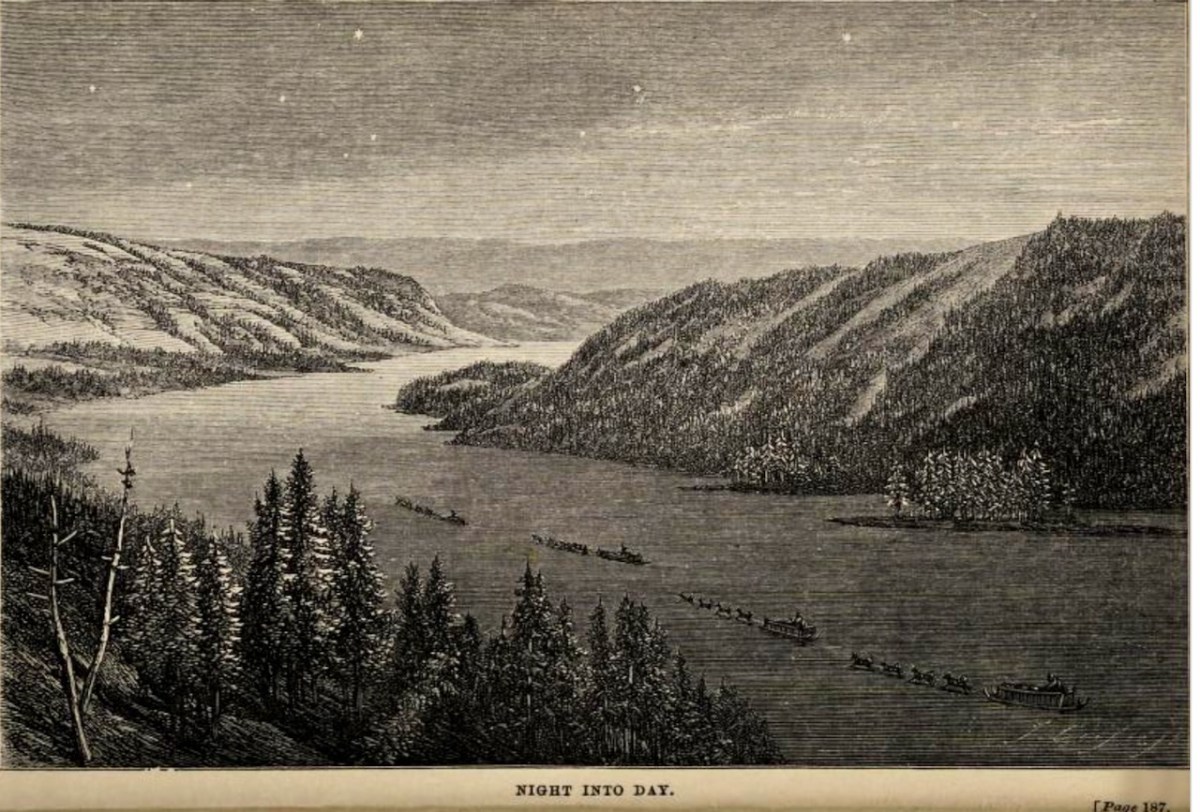

One of our resources for what life was like in early British Columbia was a book, The Wild North Land, by an Irish man – William Francis Butler (below). That’s my copy, above, but it is available on good old archive.org. What a man – adventurer, soldier, writer – he became one of my heroes. He undertook a journey across the wilds of Canada, in the footsteps of the fur traders, in the 1870s, living as they would have lived. So I am illustrating this post with pictures from that book. HIs map is part of his epic journey – the part that contains the Peace River. Try to find Fort St John on it – that’s where I was digging.

Reilly has done a masterful job of piecing together what can be gleaned from sparse documentation. He has tried to be as accurate as possible, but his pen runs away with admiration for his subject and with his enthusiasm for his deeds. What is clear is that Murphy joined the Hudson’s Bay Company as a clerk in 1816.

He was a tall young man with naval experience in the East India Company already, and his physique, courage and talent shone through in his various assignments. Here’s a mention in a dispatch:

I send you a young clerk by the name of Murphy who has been engaged for the service by Auldjo of Montréal. He is totally without experience in the fur trade, but I think you will find him active, zealous and intrepid. He is rather inclined to be wild and will be the better of being under strict discipline. But I have observed many marks of good principles and I am confident he is disposed to act right if the line of his duty is distinctly pointed out to him.

and another`;

A very steady, spirited and enterprising young man; who bears privations and hardships with cheerfulness and has conducted himself in every undertaking he had to perform with credit and satisfaction.

From a different source, by B G Mac Carthy, comes what is likely an accurate description:

To hold one’s own under such grim conditions one needed to have great courage and tremendous physical endurance. Murphy was now a man of well over six feet in height, of mighty frame and muscle. His strength, daring, honesty and unusual intelligence made him an invaluable servant of the Company. From the beginning he had to prove his mettle, since he seems always to have been chosen for the most hazardous tasks. Immediately on his first arrival at New Brunswick House he was sent to capture two men of the North West Trading Company who were wanted for robbery. It was then late autumn. None but an experienced woodsman, hunter and fighter could hope to survive in that wild and frozen land.

Several tales are told of his popularity with the Indians*, and through their liking for him many new faces were seen coming to trade at New Brunswick House, the post he was put in charge of. There is also a six year hiatus in the records in which it is unclear where he was and what he was doing, but he may have been living in Canada and pursuing life as an independent trader. It is during this period he is thought to have been adopted by a Indian community and given the name Black Eagle of the North.

This account is from his nephew, Colonel Hickie.

Soon he became restless; and one day, with a party of trappers, he left the settlement and struck into the heart of the forest. While on the March he encountered a tribe of Indians, with whom he threw in his lot and wondered through the wilds of Canada for 12 years. Crowned with feathers, dressed in skins, and with a painted face, the Indians loved him. He was elected their chief and was known as the black eagle of the North.

The whole idea of becoming a Blood Brother and living as a chief among the Indian community is very Boys Own – the stuff of many a romantic wild west melodrama. However true all this was, the soubriquet followed him when he left Canada and eventually, via Rome, ordination, Liverpool and Cork, arrived in Goleen at the height of the Famine, riding his black ‘charger’ and tasked with winning back the souls of the Soupers of Toormore. It is mentioned in his obituaries, so it was obviously part of his mystique and reputation for the rest of his life.

He didn’t stay long in Goleen, possibly less than a year and the rest of his days were spent in Cork, where he built the magnificent Church of Peter and Paul in Paul Street. He died an archdeacon, with a reputation for charity and kindness to the poor and a saintly disregard for his own comfort.

His life has inspired Reilly’s book, but also two essays, both of which seem equally full of fanciful accounts, some of which are based on reminiscences from family members. The lengthy quote in Part 6 of Saints and Soupers that starts The scene changes to a clearing in the virgin forests of Canada is from White Horsemen by M P Linehan, and the quote from Col Hickie is from this piece.

*I use the term here as it is used in the original documents, but the accepted term now for indigenous Canadians is First Nations people

Here is the page with links to the complete Saints and Soupers series.

Discover more from Roaringwater Journal

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thoroughly enjoyable read Finola.

I loved it.

LikeLike

Thanks, John!

LikeLike

Thoroughly enjoyed this. And what great, atmospheric pictures!

LikeLike

Thanks, Michael – the pictures made it, I think.

LikeLike

A great read – thank you. Interested to hear of your own research into early trade forts and the HBC. It’s amazing that any of the Europeans survived the harsh winters – they had to be so resilient and adaptable. That mountain in the background of ‘cutting up the moose’ is jawdroppingly steep!

LikeLike

I think

That mountain owes much to the artist’s imagination. This was a lovely post for me to write, bringing back so many memories.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Finola. Surely fascinating for every reader, but perhaps particularly for me, as a current member of the congregation at Teampol na mBocht! I suppose the Saints v Soupers controversy will never be resolved, as the motives of all parties were so mixed.

LikeLike

A wise comment, Francis! I may have more in the series yet.

LikeLike

What a man – I love the image of him as inclined to wildness; and later with feathers in his hair! A life lived fully!

LikeLike

The face paint and feathers seem like a fanciful addition – but it all adds to the myth.

LikeLike

This is a great story. Thank you for reviving it.

LikeLike

They don’t make ‘em like that any more. 😊

LikeLike