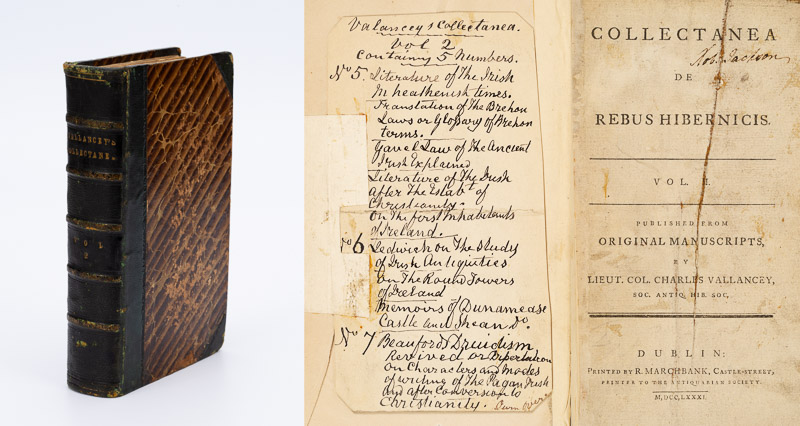

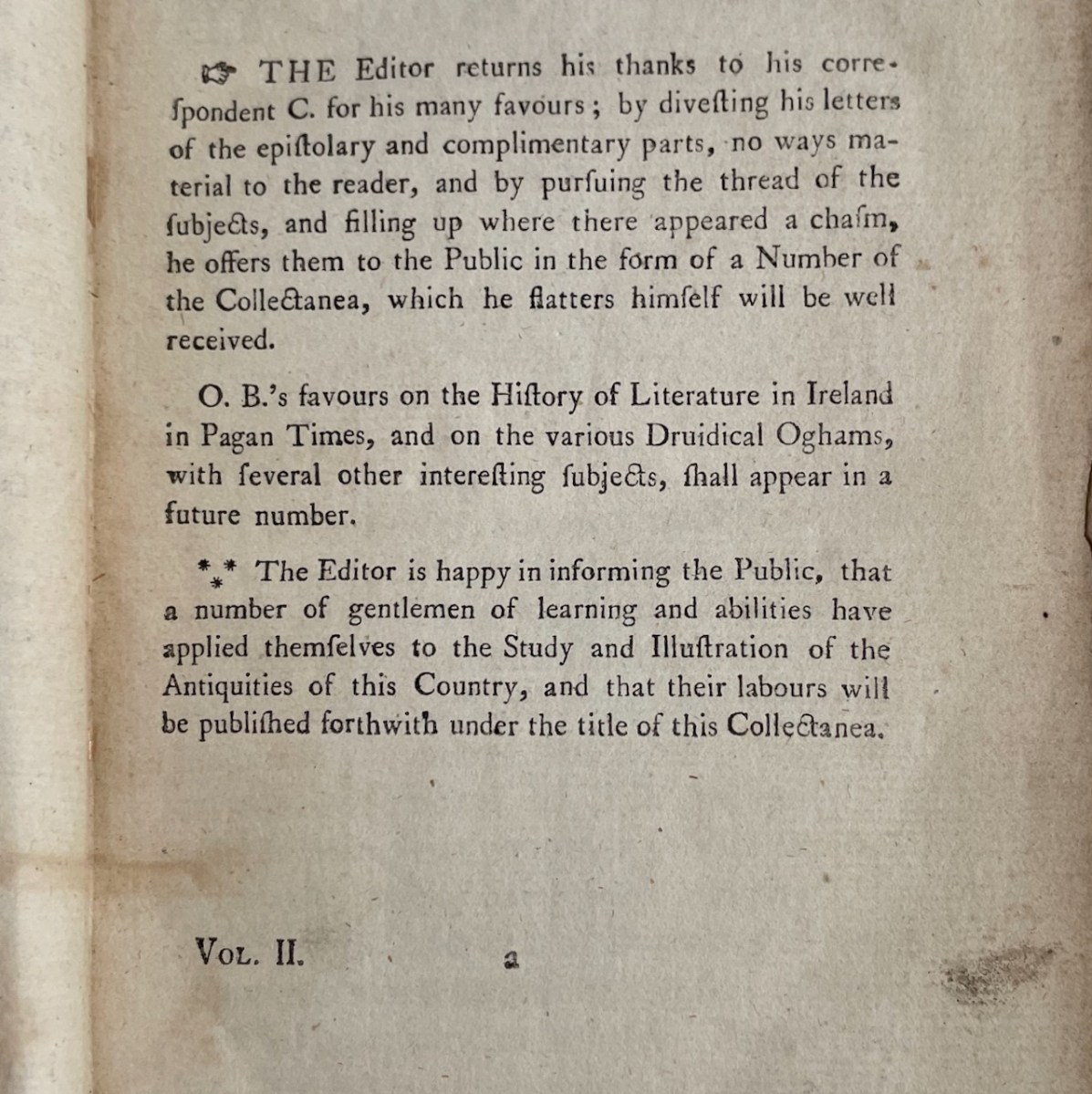

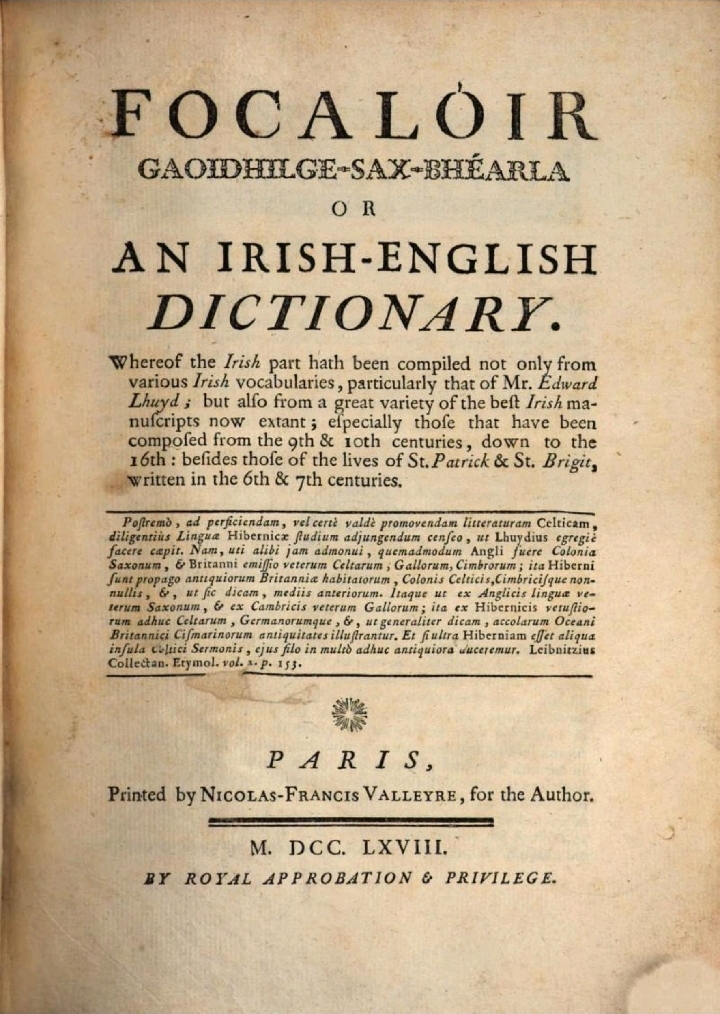

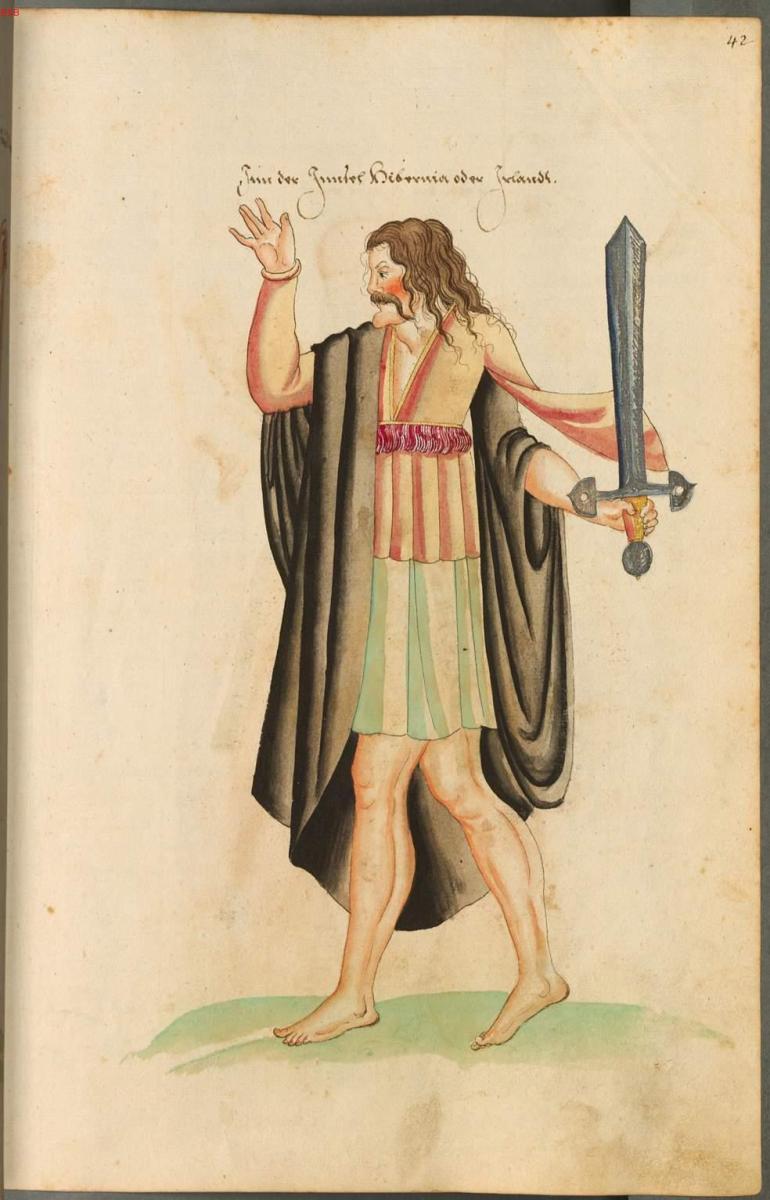

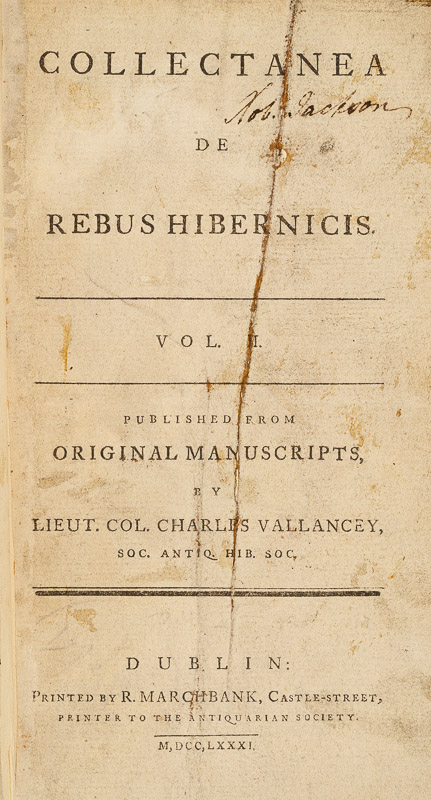

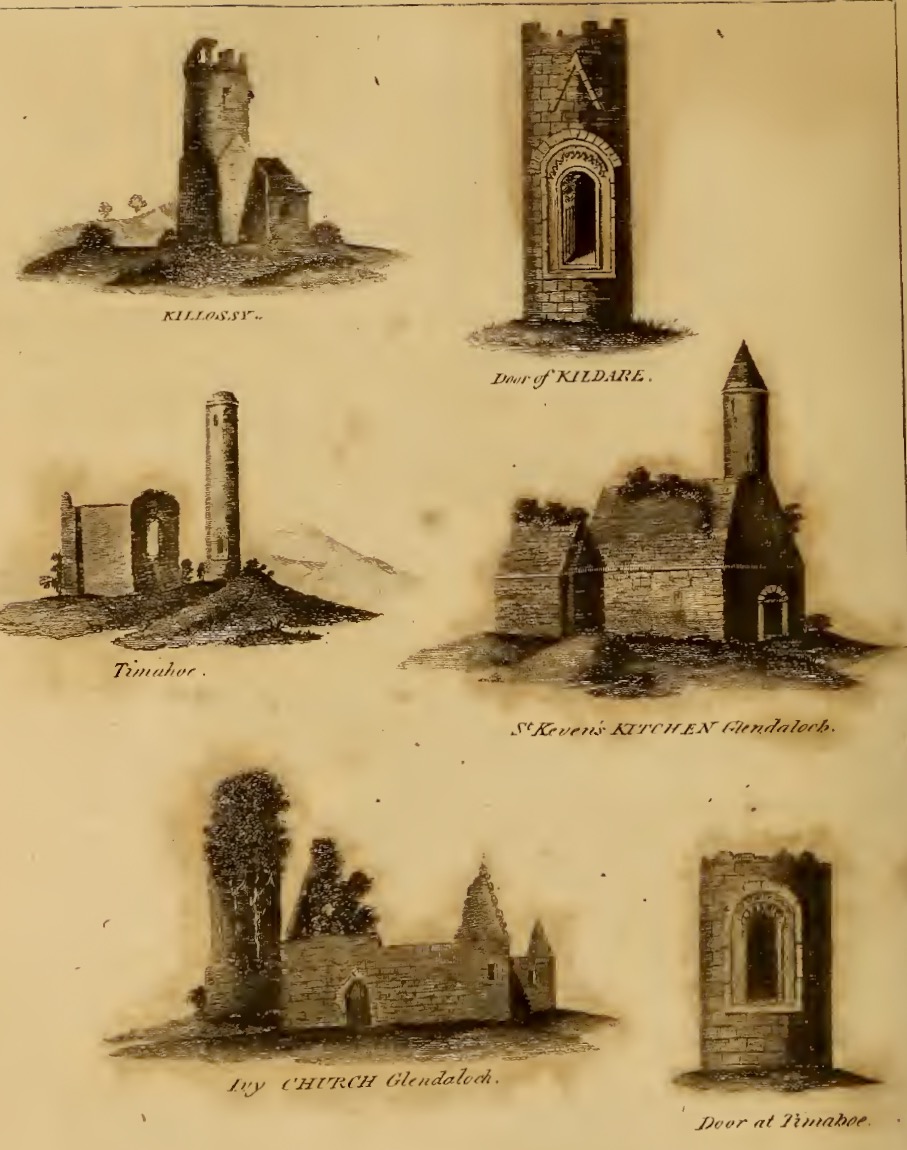

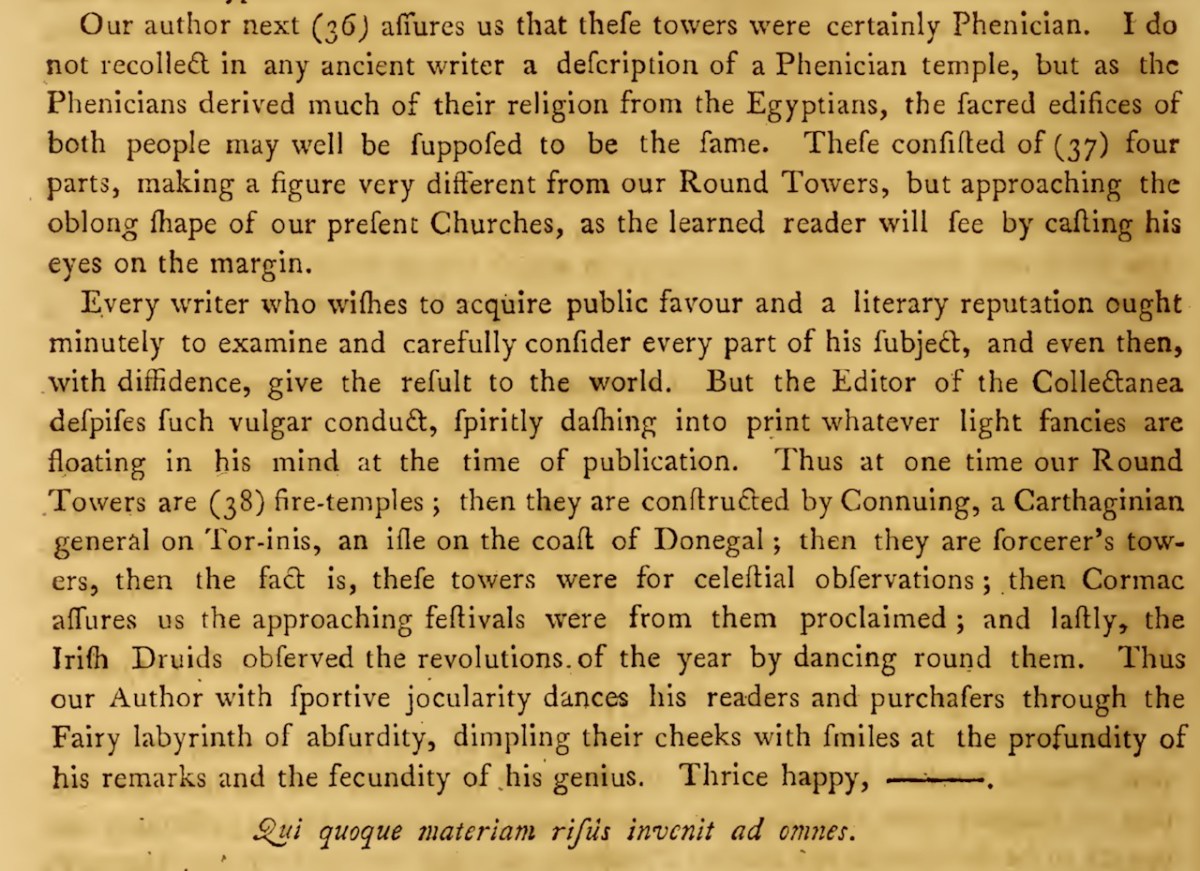

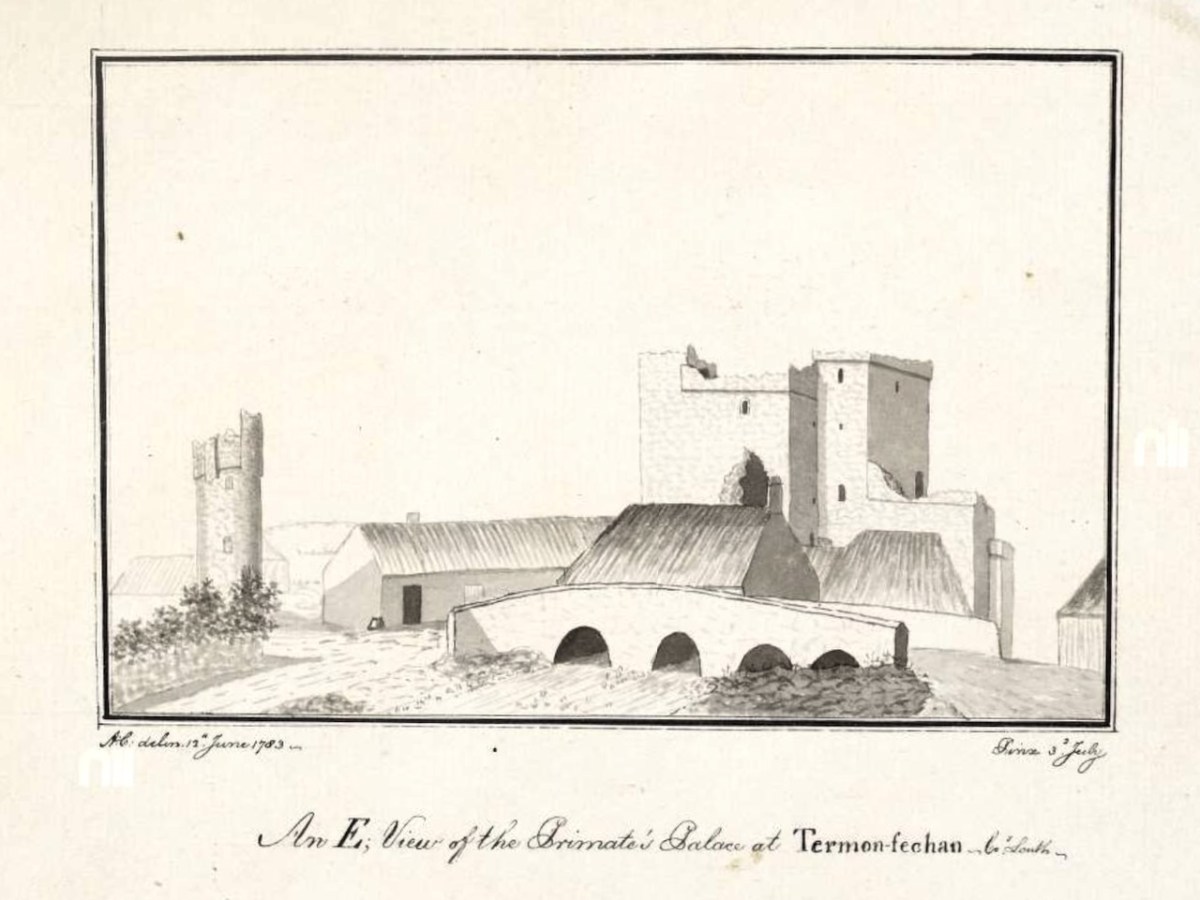

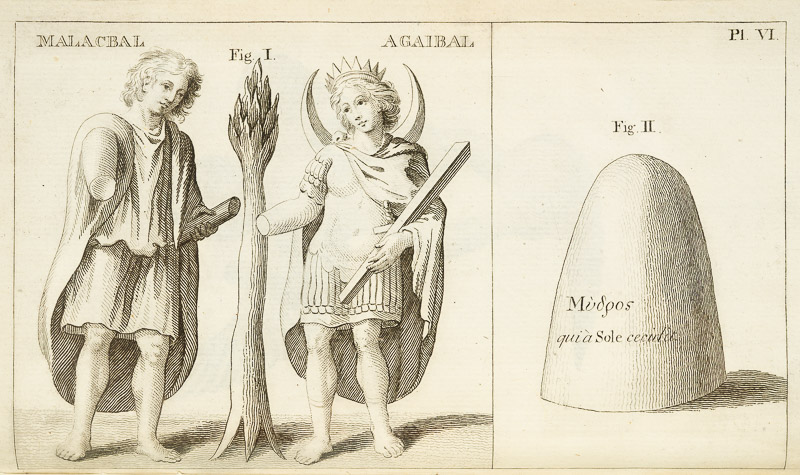

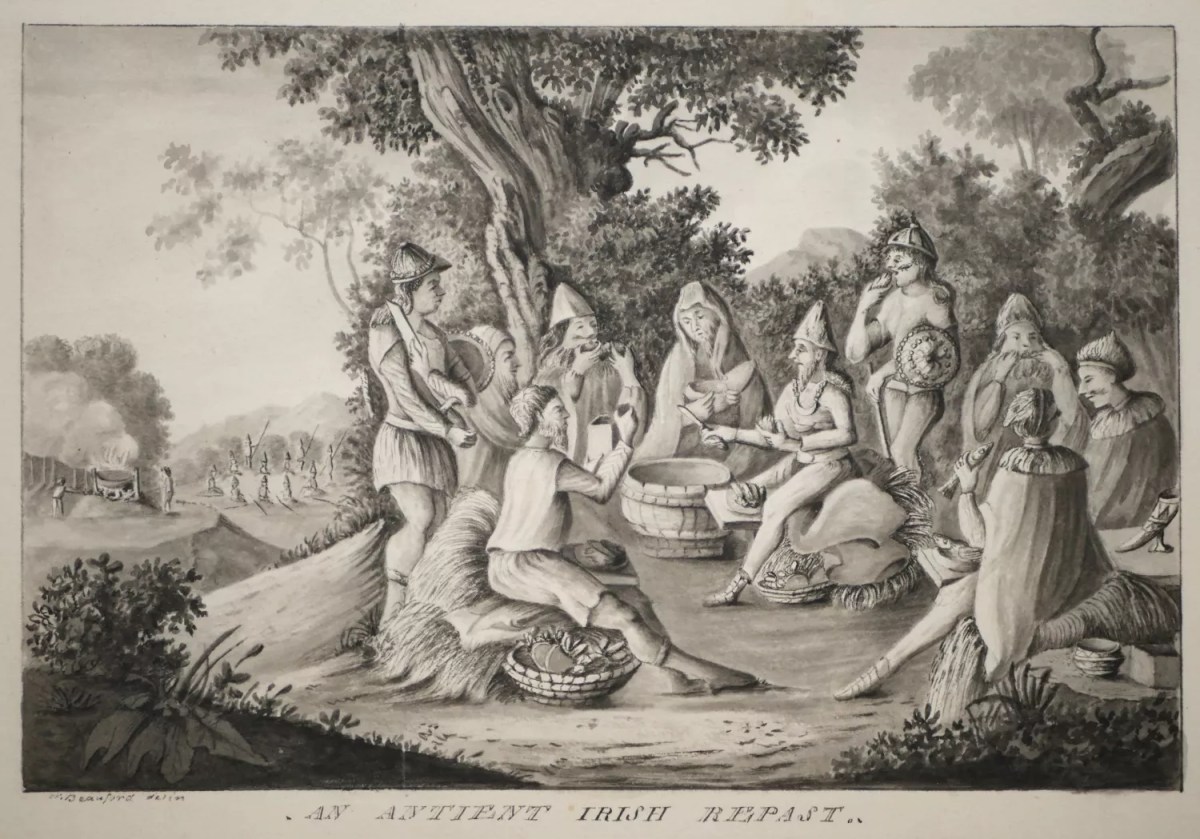

I took a breather last week, but I’m back with more Vallancey. I’ll dispatch Vol 2 as quickly as possible now by telling you that it contains a section on Druidism by William Beauford, an ardent student of Irish antiquities and ancient music and an accomplished draughtsman. He, along with Vallencey, Wm. Burton Conyngham, Ledwich and others, founded the Hibernian Society of Antiquarians – the ill-fated organisation that broke apart under the strain of the quarrels between Vallancey and Ledwich. He was also an artist, contributing drawings to several publications. Below is a piece of his I found online. I think it’s an evidence-free depiction of how these antiquarians saw the antient Irish. And – is the man on the right about to bite the head off a fish?

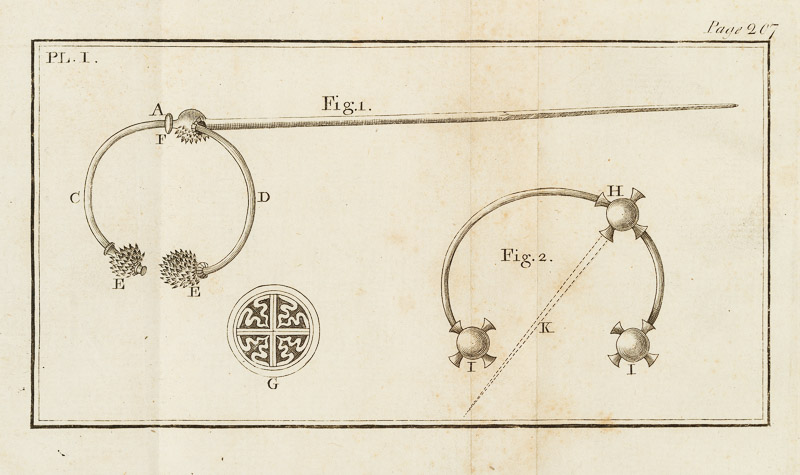

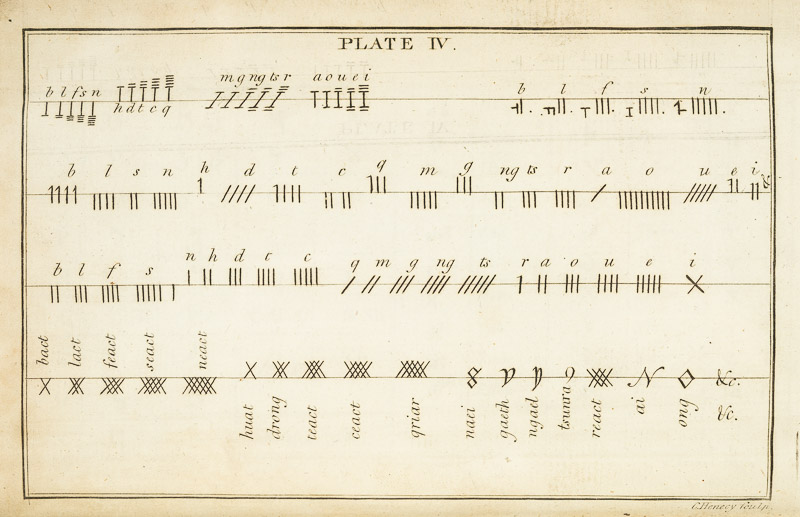

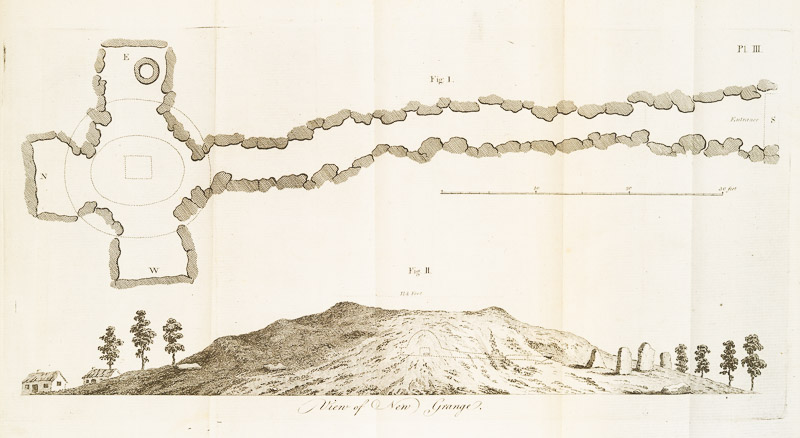

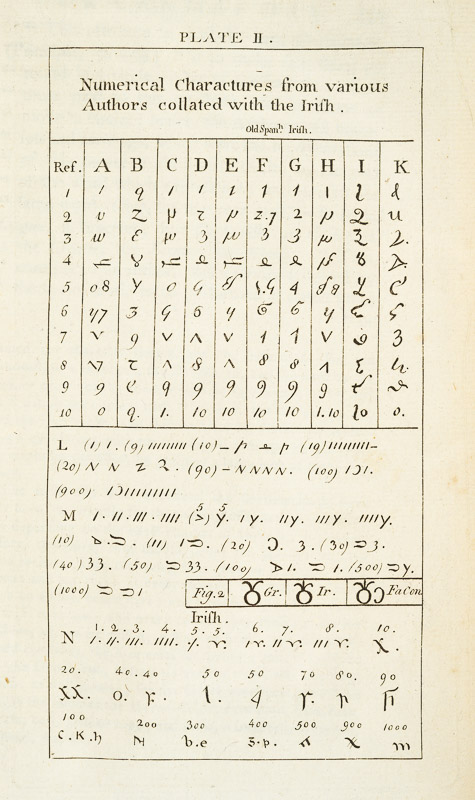

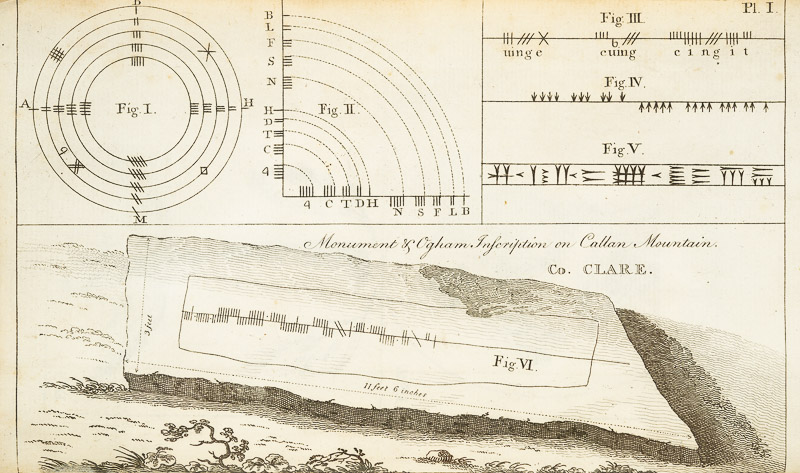

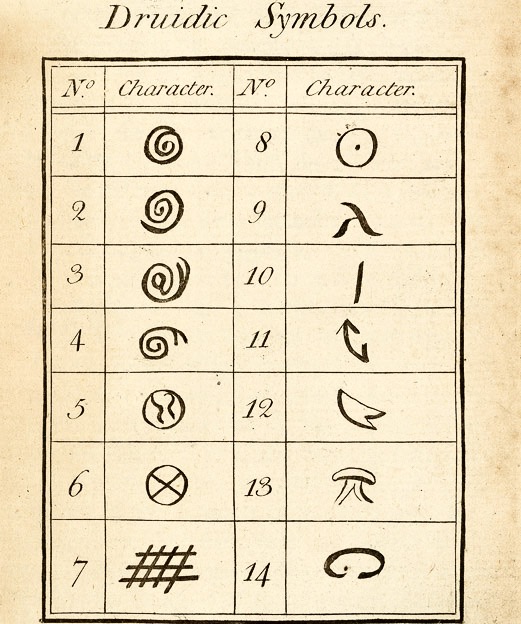

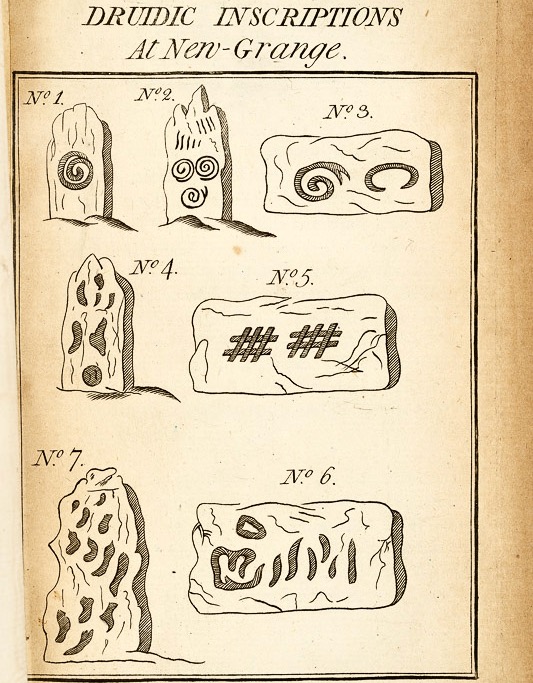

In this piece, his thesis was that the druids had writing long before Christianity and we can see their symbols in Newgrange and other places and figure out their meanings. Since the cup and circle is the central motif of Irish rock art (on which I wrote a theses) I was particularly interested in his interpretation of the dot-and-circle:

Number eight is a circle found on several Irish coins. The circle among the Egyptians, Phoenicians, Carthaginians etc generally represented the Sun and sometimes the World. With the Celtic Druids it also represented the Sun, and with a dot in the centre, the whole universe. The ancient Irish retained it during the Middle Ages as the symbol of a country, and with a point in the centre, for the whole kingdom, or Ireland in general.

The spiral, by the way, was a serpent, ‘symbols of the Divine Being,’ the cross hatch or trellis is the symbol of ‘fate, providence, chance or fortune.” So now!

One of the many problems with this, of course is that while Beauford asserts this all flows from Egypt, we know that Newgrange predates the pyramids and hieroglyphic writing. Another problem is that the above illustration bears no resembance ot the carvings at Newgrange. Volume 2 continues with more on Druids, including a spirited defence of the ancient beauty of the Irish language, which “should be taught in our university”, and a grammar of Iberno-Celtic. As might be expected, there is much discussion here about Phoenicians and Carthaginians.

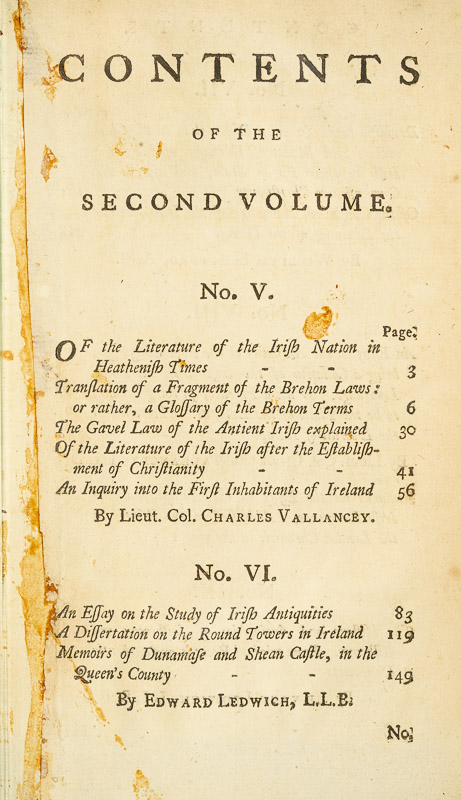

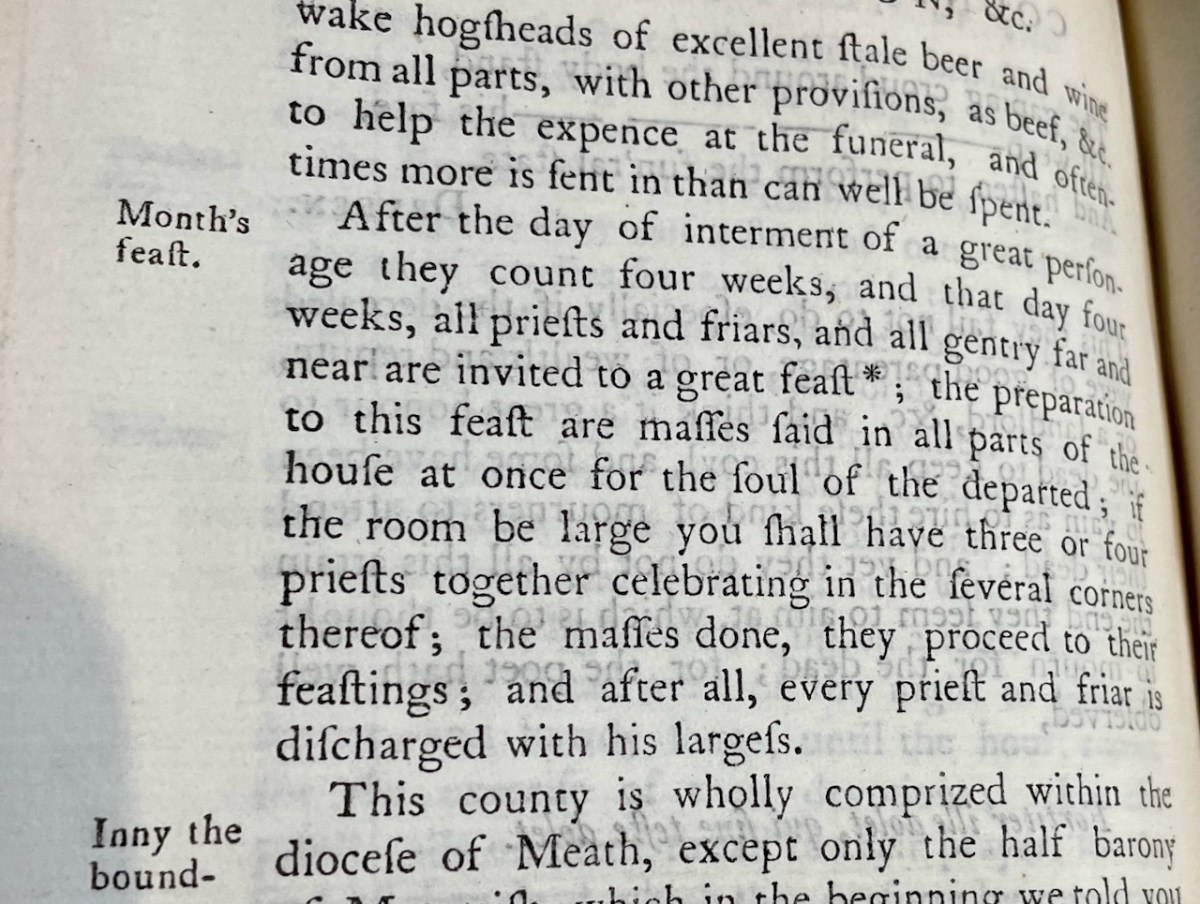

There’s more, but I’m going to move on now to Vol 3. At last – I hear you cry! This one is full of more arguments about the origins of the Irish and our language, including a lengthy section on ‘Japonese’ and Chinese ‘collated with the Irish’. And, as is his wont Vallancey provides his usual lengthy preface (70 pages!), full of interesting titbits. One that caught my eye was his claim that the Irish word Pósadh, meaning marriage, was based on the word Bósadh (Bó is a cow in Irish), and the sense of it was a dowry ‘endowed with cows’. Asserts Vallancey:

The men of quality amongst the old Irish never required a marriage portion with their wives, but rather settled such a dowry upon them, as was sufficient maintenance for life, in case of widowhood.

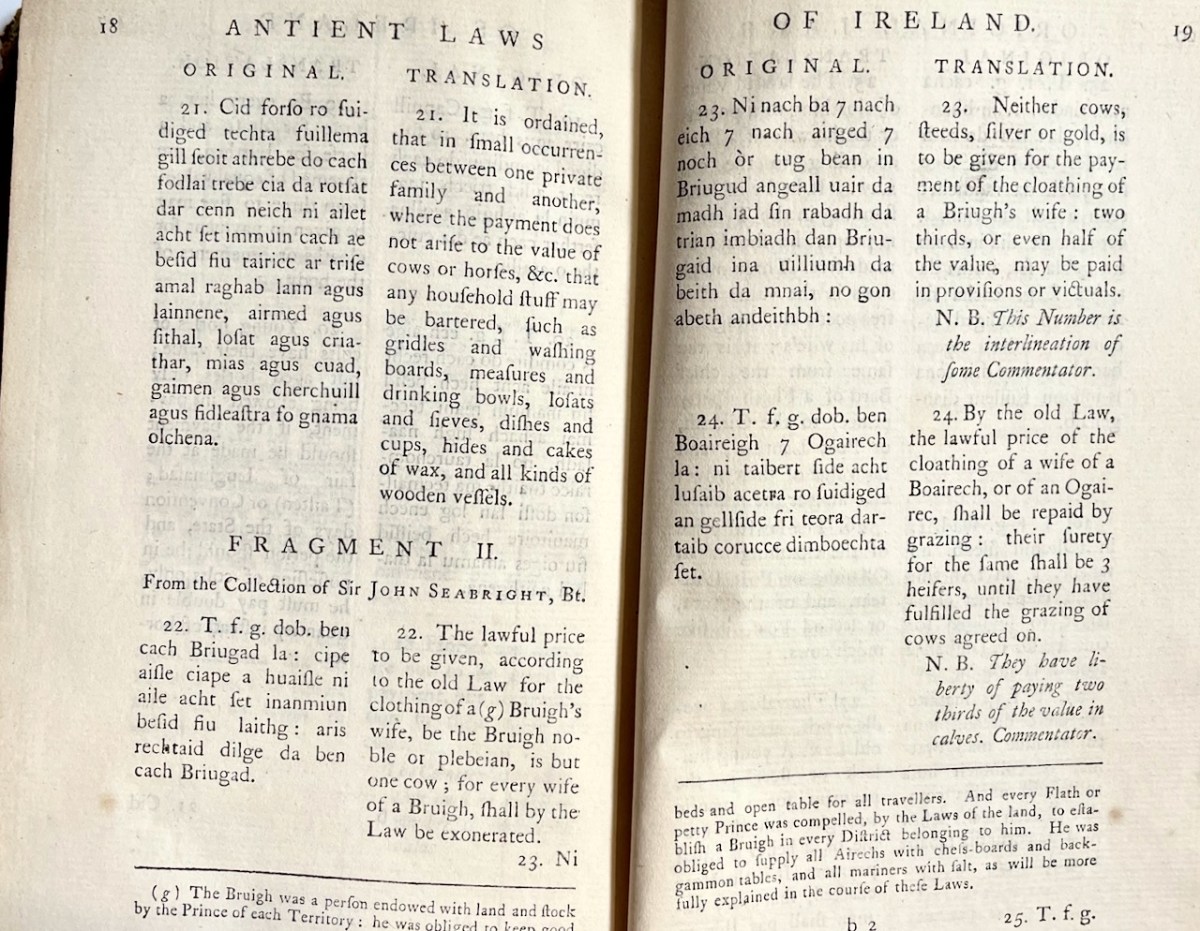

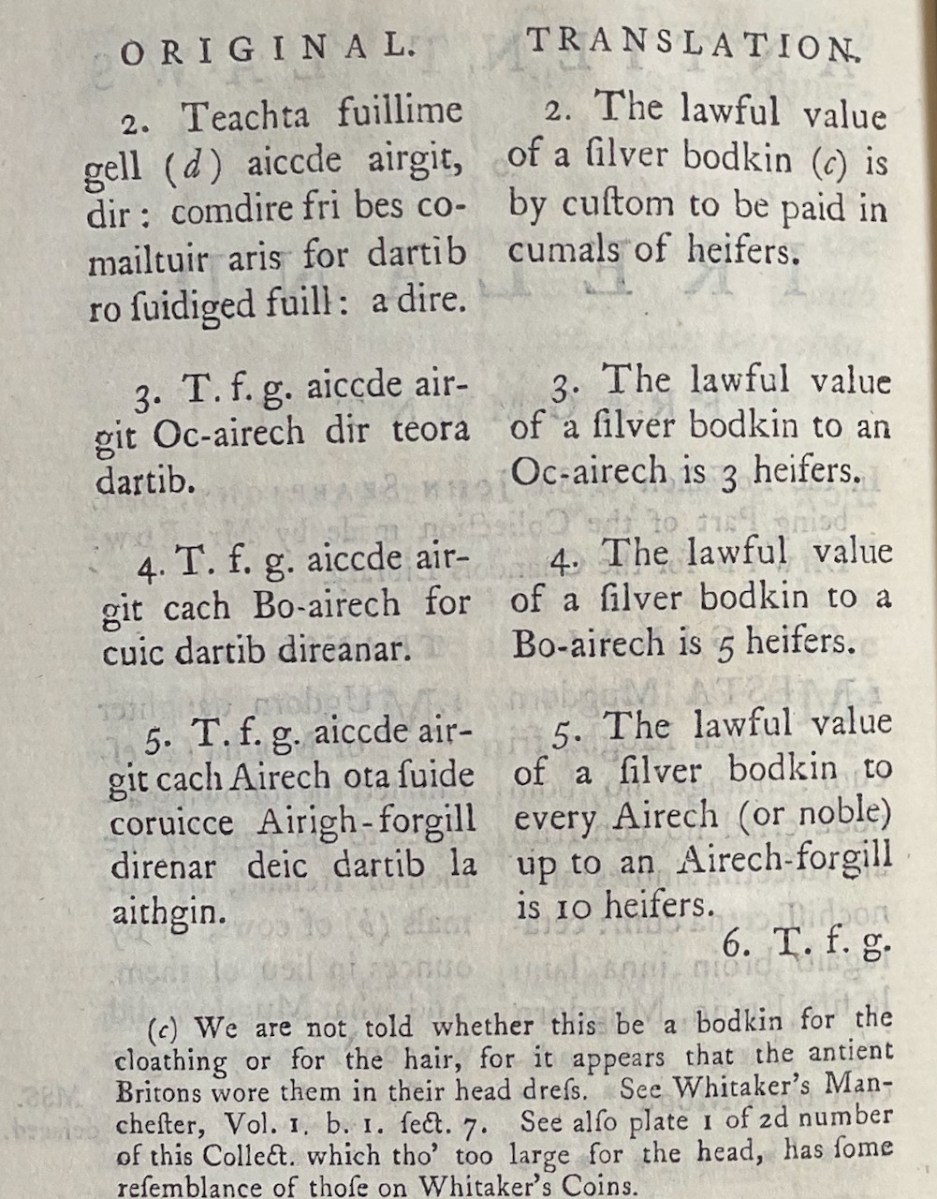

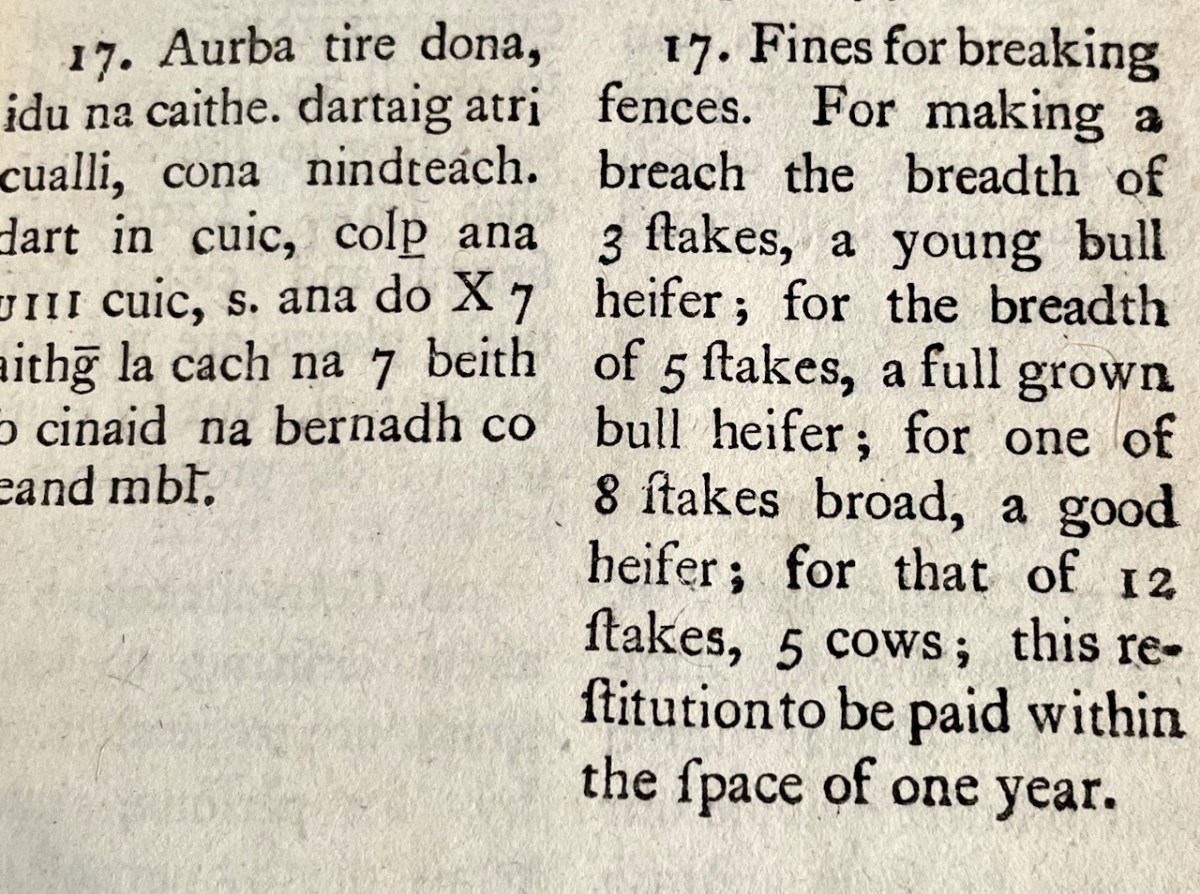

He can’t resist adding and this was the custom of the German nobles and of the Franks. This is followed by another interesting section on the Brehon Laws. These laws of medieval Ireland (a Brehon was a judge) were concerned mostly with fines and compensations for wrongdoing, and this section deals for example with trespass.

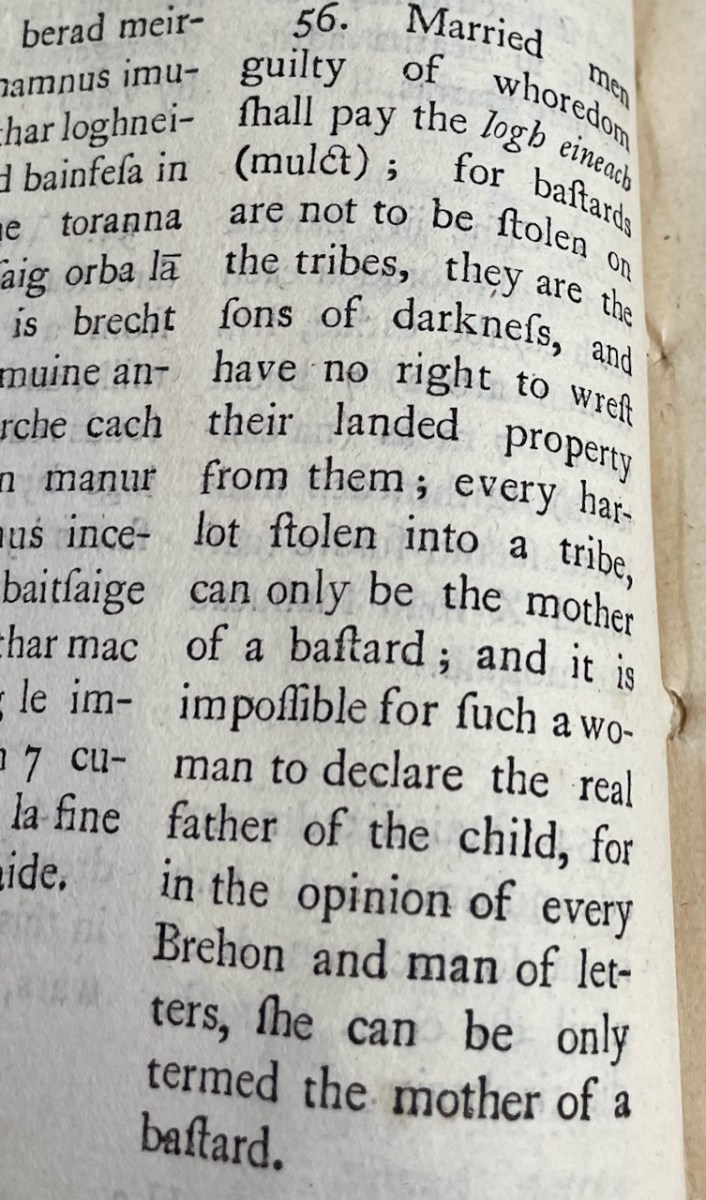

It also talks about children born to unmarried women. Although it refers to men guilty of ‘whoredom’ and the logh eineach (honour price) they must pay, it goes on to say that such bastards are sons of darkness and must not be foisted upon the tribe by the harlot. Here we see how important it is to preserve inheritance within the ruling sept of the tribe, and how women were expendable in that process.

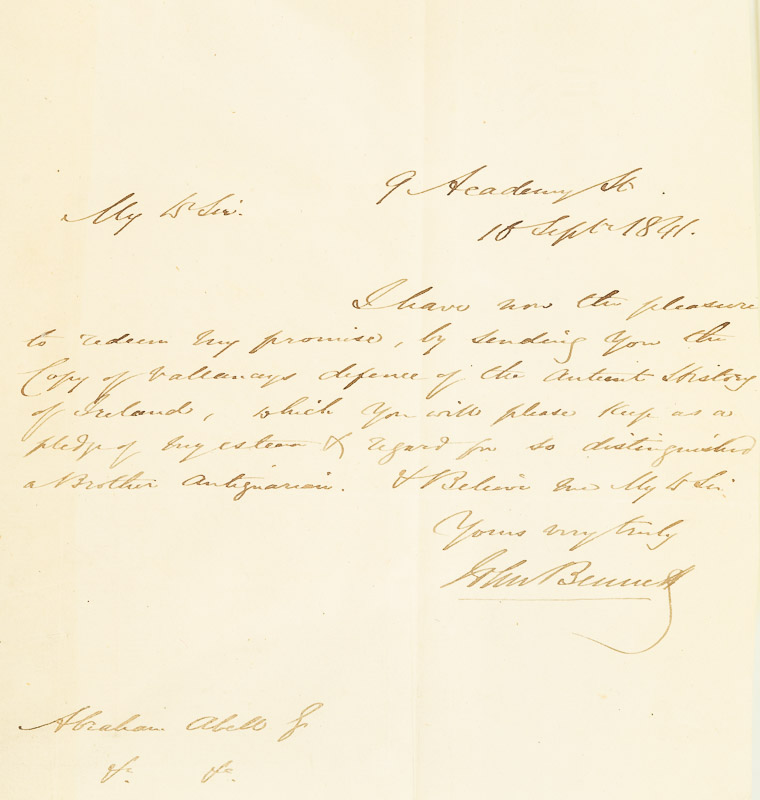

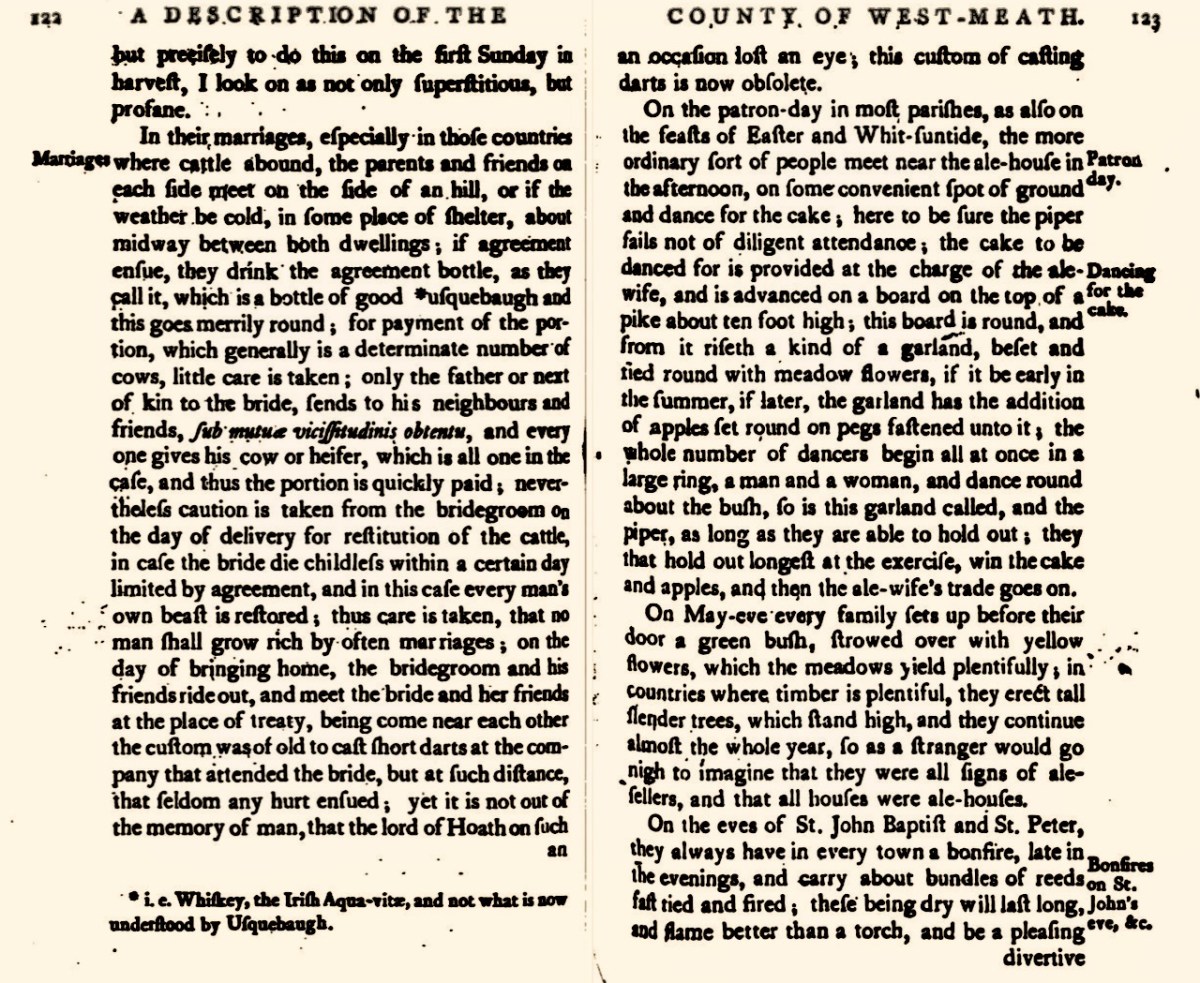

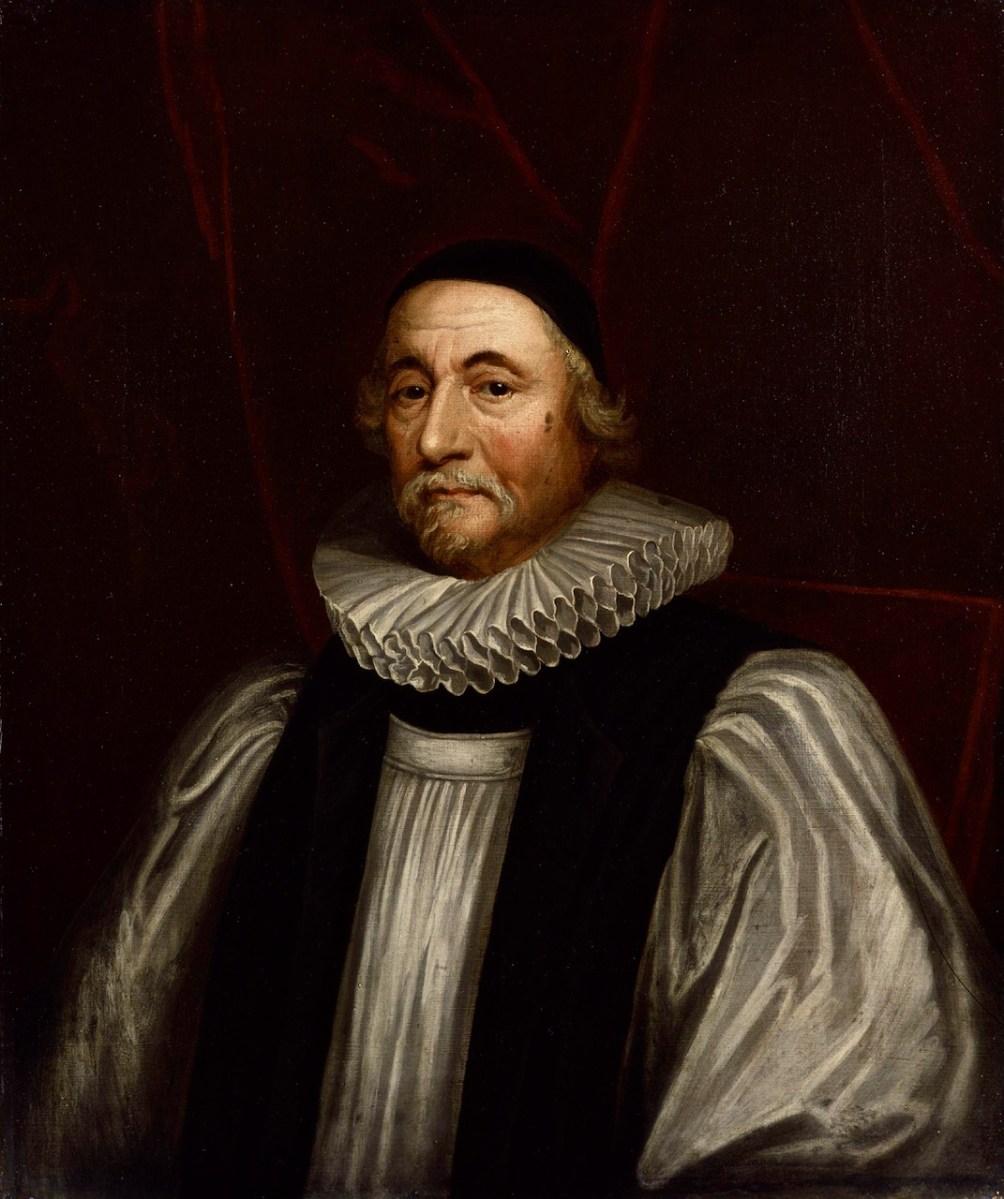

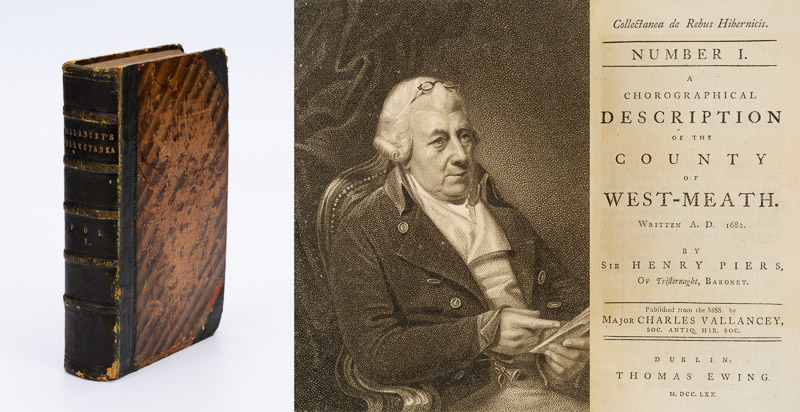

And now we come to yet another of the cohort of antiquarian scholars that were contemporaries of Vallancey – Charles O’Connor of Belanagare. Perhaps the most learned of them all, O’Connor came from old Irish nobility. See the fascinating biography of him in the always-superb resource from the Royal Irish Academy – the Dictionary of Irish Biography. Fluent in Irish and a collector of manuscripts, he was connected to many gifted and interesting scholars and scribes in Irish. and eventually acquired or obtained sight of practically every important Irish manuscript in the country. He was, with Vallancey, one of the founders of the ill-fated Hibernian Antiquarian Society, and later the Royal Irish Academy. The portrait below is from Wikimedia Commons.

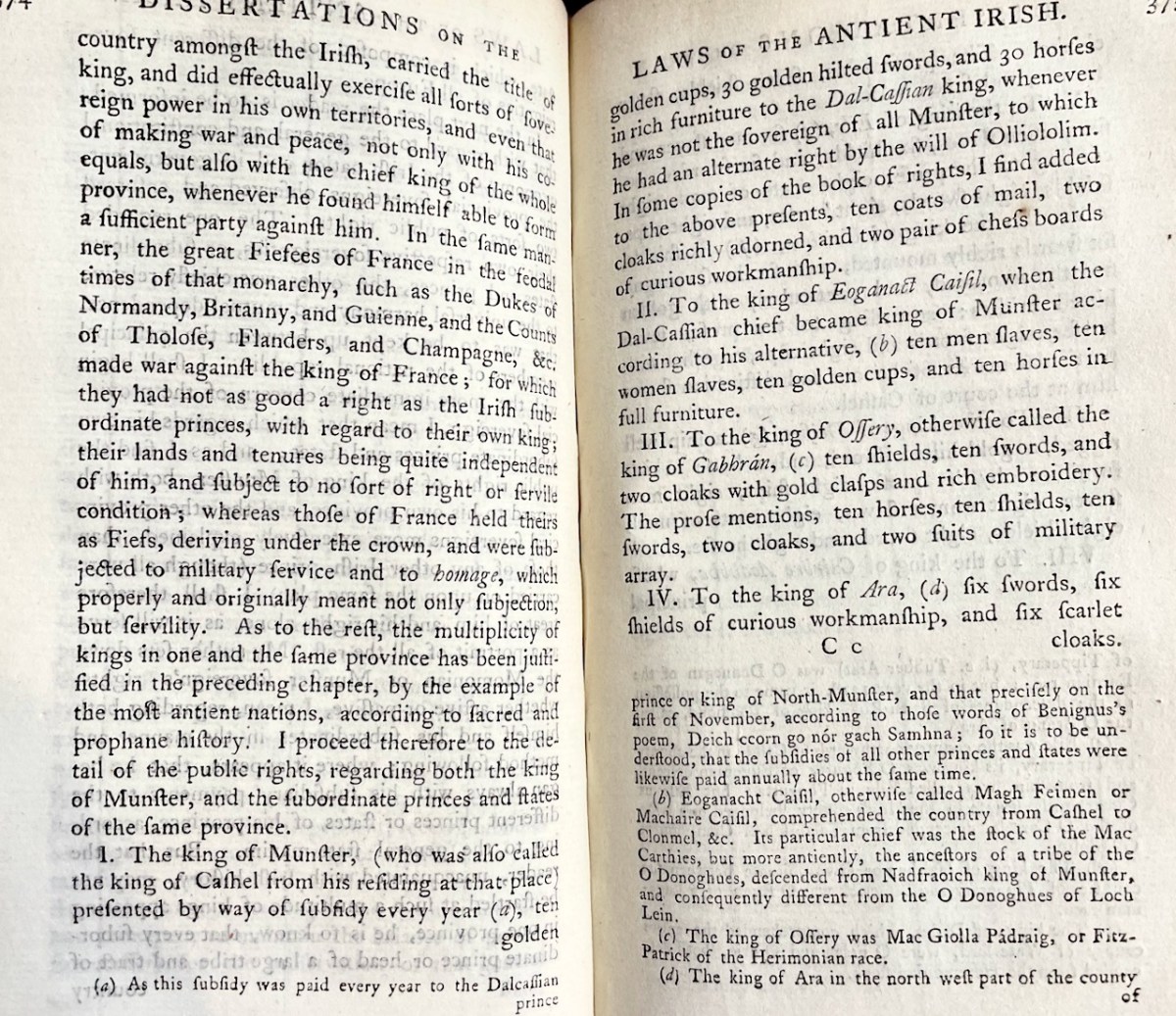

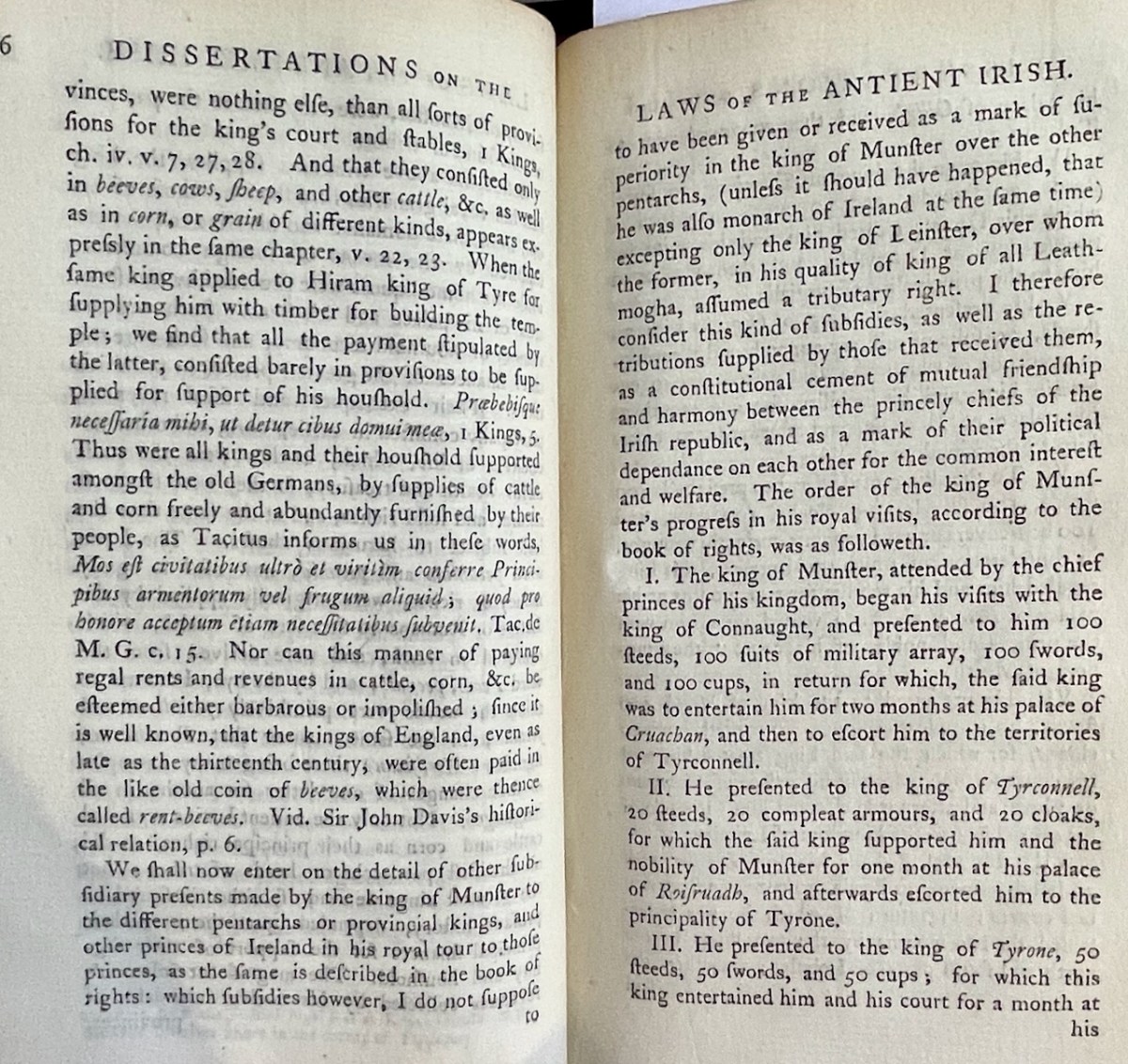

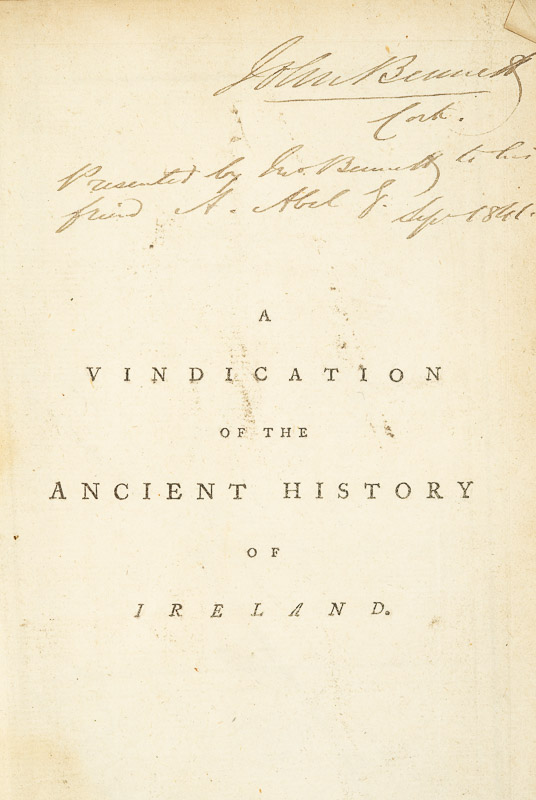

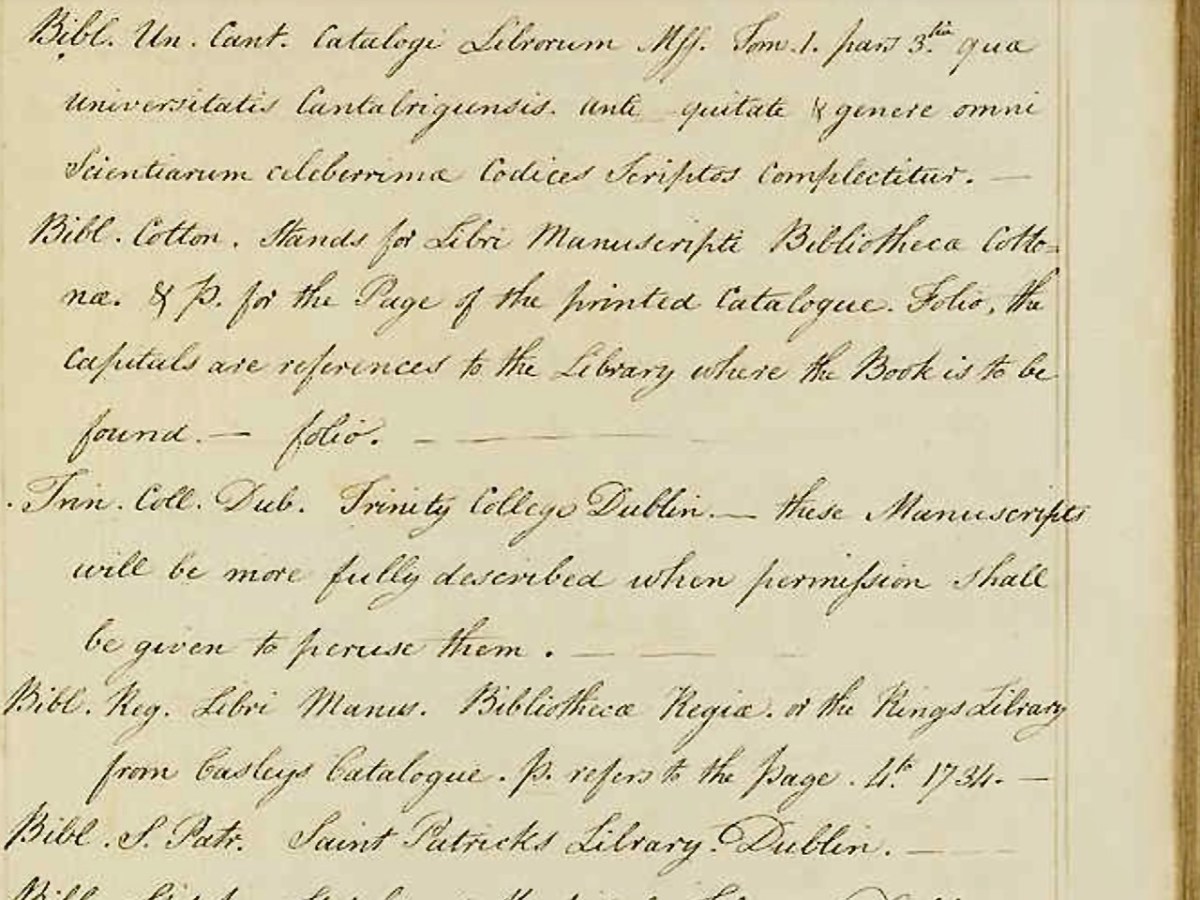

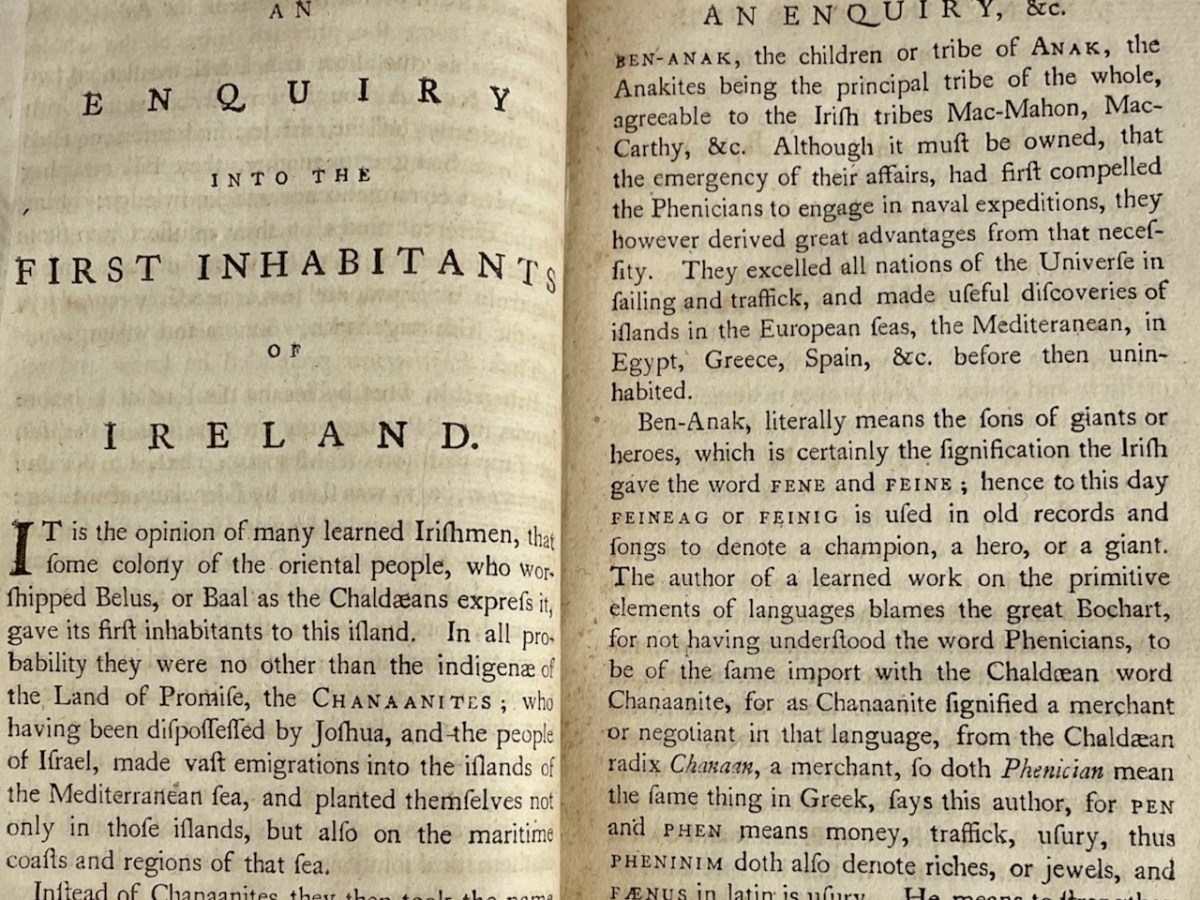

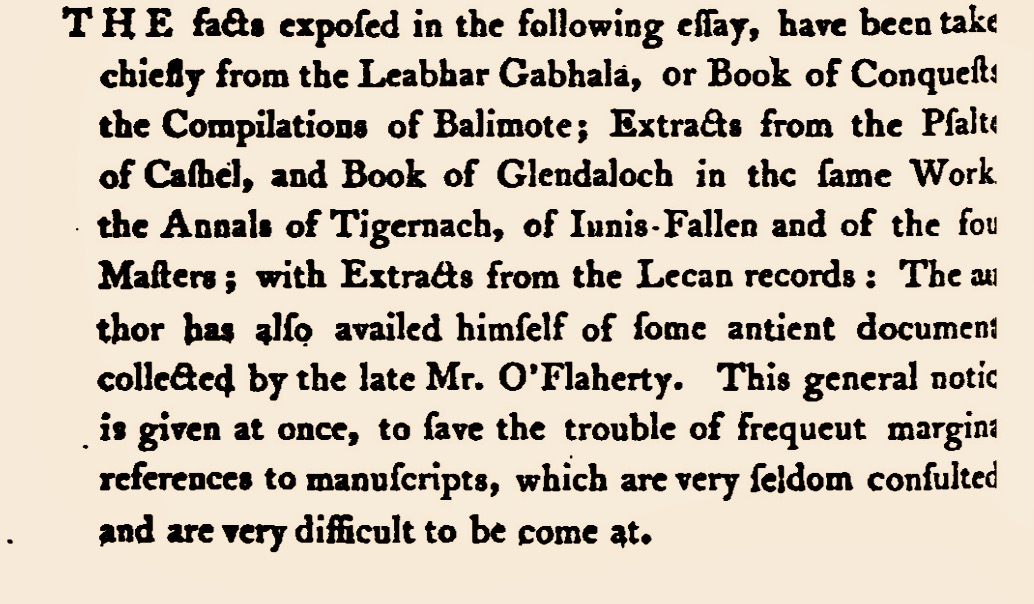

He had previously written a manuscript titled Dissertations on the antient history of Ireland in 1753, but for this volume of the Collectanea he produced a further essay, a letter really, addressed to his friend Vallancey, titled Reflections on the History of Ireland During the Times of Heathenism. In it, he coined the term “Fenian” for Fionn MacCumhaill’s band of warriors, a term that certainly had sticking power in Irish History. In this letter he appears to support Vallancey’s daft ideas about Phoenicians. However, he was a better scholar than Vallancey and pioneered the use of primary sources including manuscripts from his personal collection, to research and write about Irish history, and his familiarity with these sources is obvious in this piece. Here’s his list.

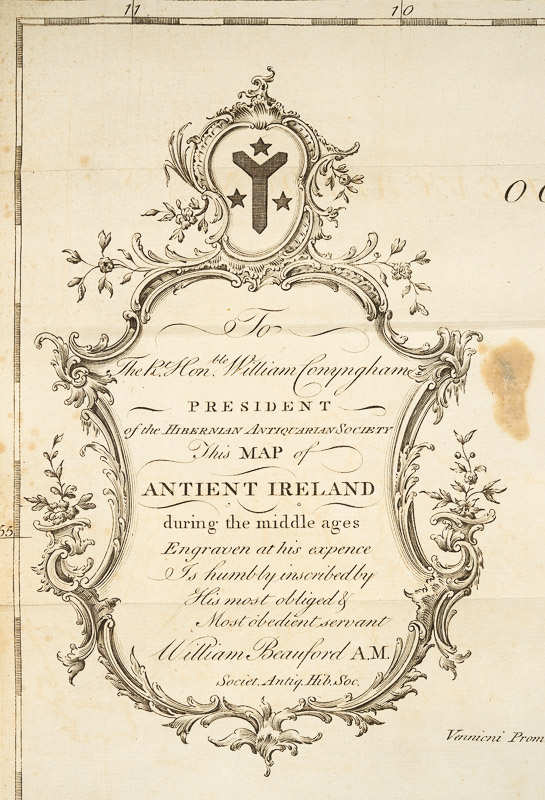

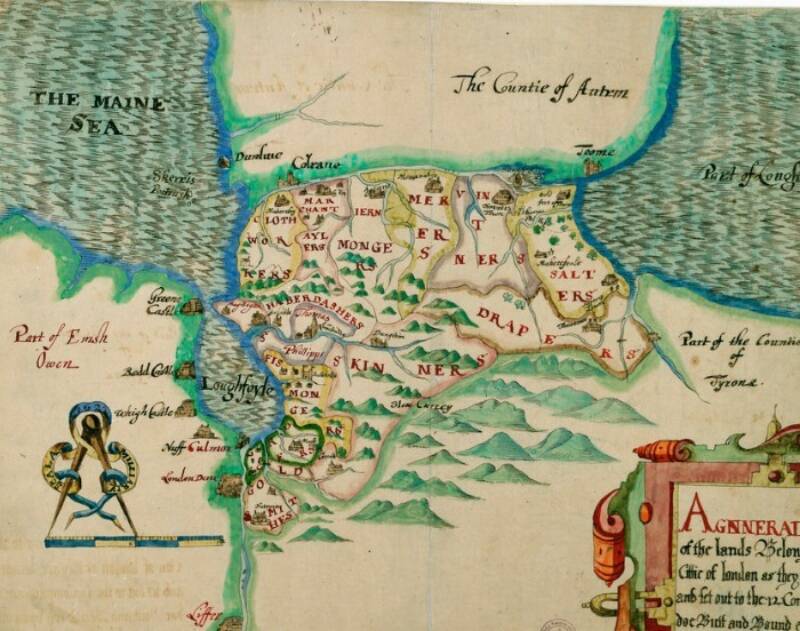

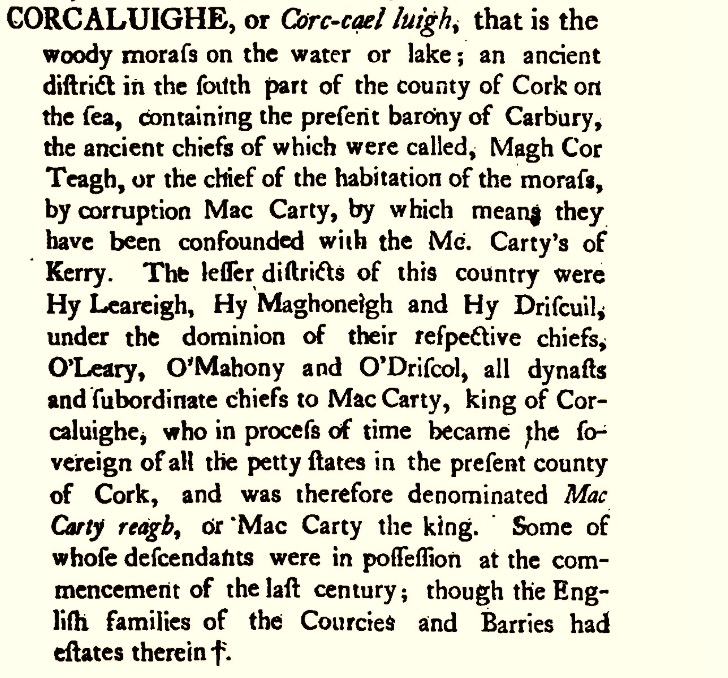

William Beauford makes another appearance now, with his Antient Topography of Ireland. Unlike what it sounds, this is actually a dictionary of place names, with an explanation of the meaning of the name and some historical associations.

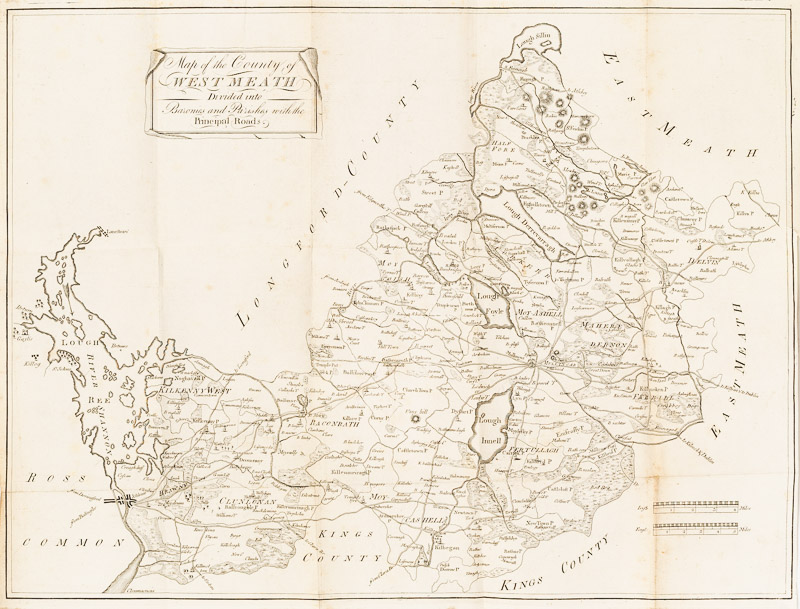

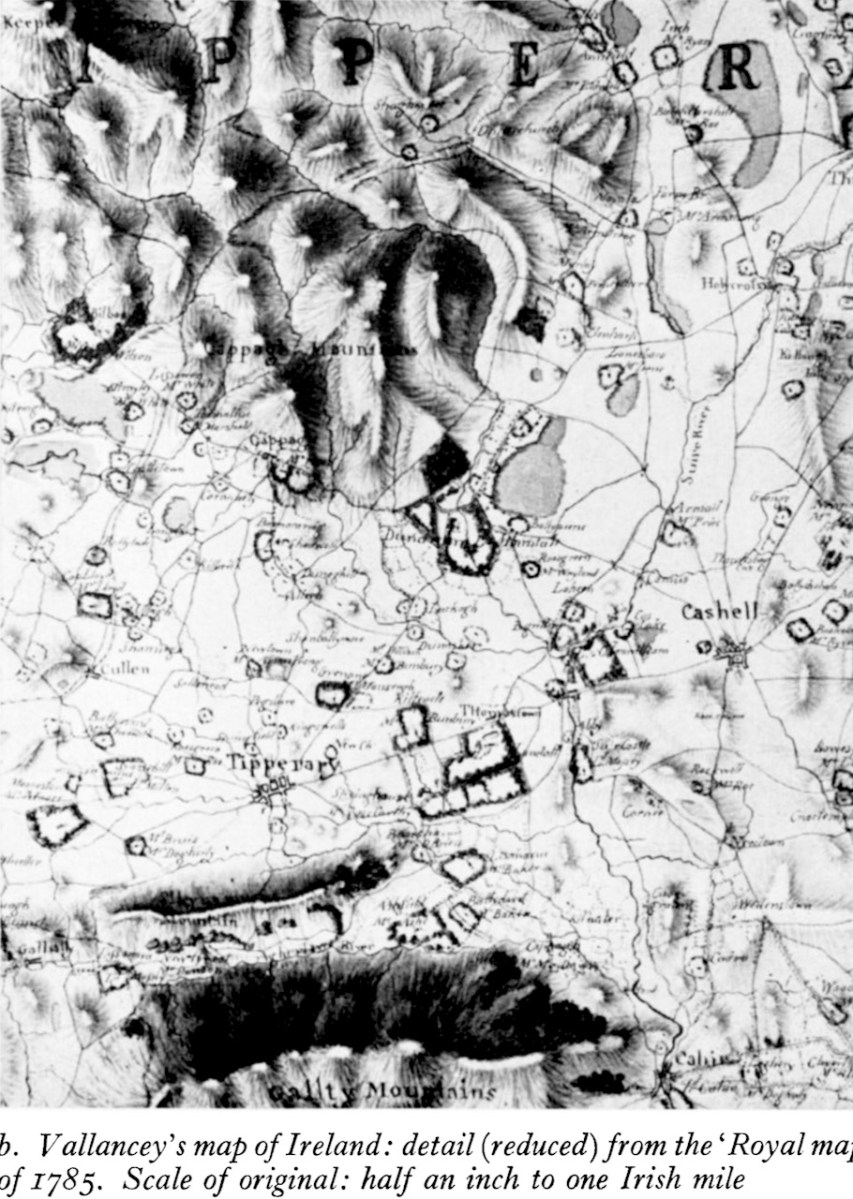

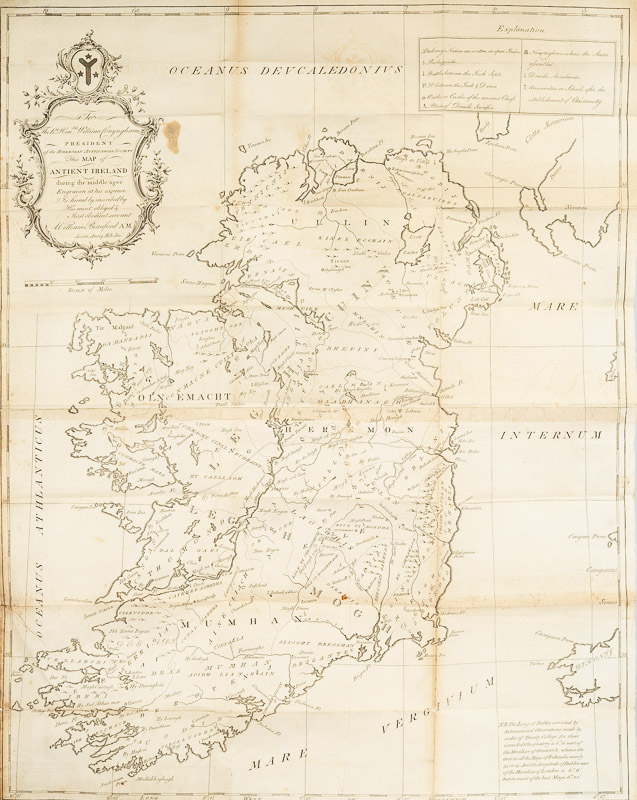

However, there is also a wonderful map! It’s a fold out, and dedicated to yet another of the Hibernian Antiquarians, Willian Conyngham. Regular readers know how I love a good map!

And now all the dictionary entries become clear, as Beauford matches the placenames with the map.

Above is his section on Corcaluighe (Pronounced Kurka Lee) while below is the section of the map showing the location of Corcaluighe.

Of course, I had to choose West Cork. But just to show you how broadminded I am, here is the area around Dublin. How many names can you make out?

I’ll leave it at that now for Volume 3. I’m actually still only half way through it, but I’m going to skip over the rest of it now, in favour of covering 4 and 5 next time – at least that’s the plan! Wish me luck.