We were chasing ghosts on our whole journey, following in the wake of Angela and Tom Rolt who travelled the waterways of Ireland exactly 70 years ago – in 1946; their odyssey was described in Rolt’s book Green & Silver. I received this book as a prize for essay writing when I was at school in the early 1960s and it fanned my interest in canals but also in Ireland. I had always intended to explore the canals of Ireland and this year Finola and I did just that – to mark the seventieth anniversary of the Rolts’ voyage, and to mark my own seventieth birthday.

Top picture – ghostly reflections beside the Grand Canal at Ballycowan. Above – Robert photographing the impressive sluice house on the Royal Canal Feeder at Lough Owel: sadly, the house is empty and now deteriorating

The first ghosts we looked out for were the Rolts themselves. Would anyone have remembered them? Did they make enough of an impression – two eccentric English travellers intent on discovering a way of life in Ireland which had almost ended at that time? Their book is remembered today by canal enthusiasts; in fact there is a plaque given to anyone who completes the circumnavigation of the Royal Canal, the Shannon and the Grand Canal. It’s known as the Green & Silver Route. As the Inland Waterways Association of Ireland says, …with the closure of Ireland’s Royal Canal in 1961, Rolt’s Green and Silver offered successive generations of boaters the only opportunity to experience this journey by boat. His book offered a glimpse of what might be experienced if, and when, the canal was restored. Rolt was the first to document a successful transit of the route in Green & Silver, a book which had such a positive influence on the development of the Irish waterways… The book has gone into five editions, so the journey is certainly not forgotten. However, we did not meet anyone who had stories to tell about the Rolts; nothing seems to have passed down through the generations about them – perhaps this post might bring something out?

Left – the frontispiece of my copy of the Rolts’ book. Right – the Green & Silver Plaque, presented to boaters making a circumnavigation of the now restored route that the Rolts followed seventy years ago

But there are other ghosts in the pages of Green & Silver. The Rolts passed through Draper’s Bridge Lock on the Royal Canal:

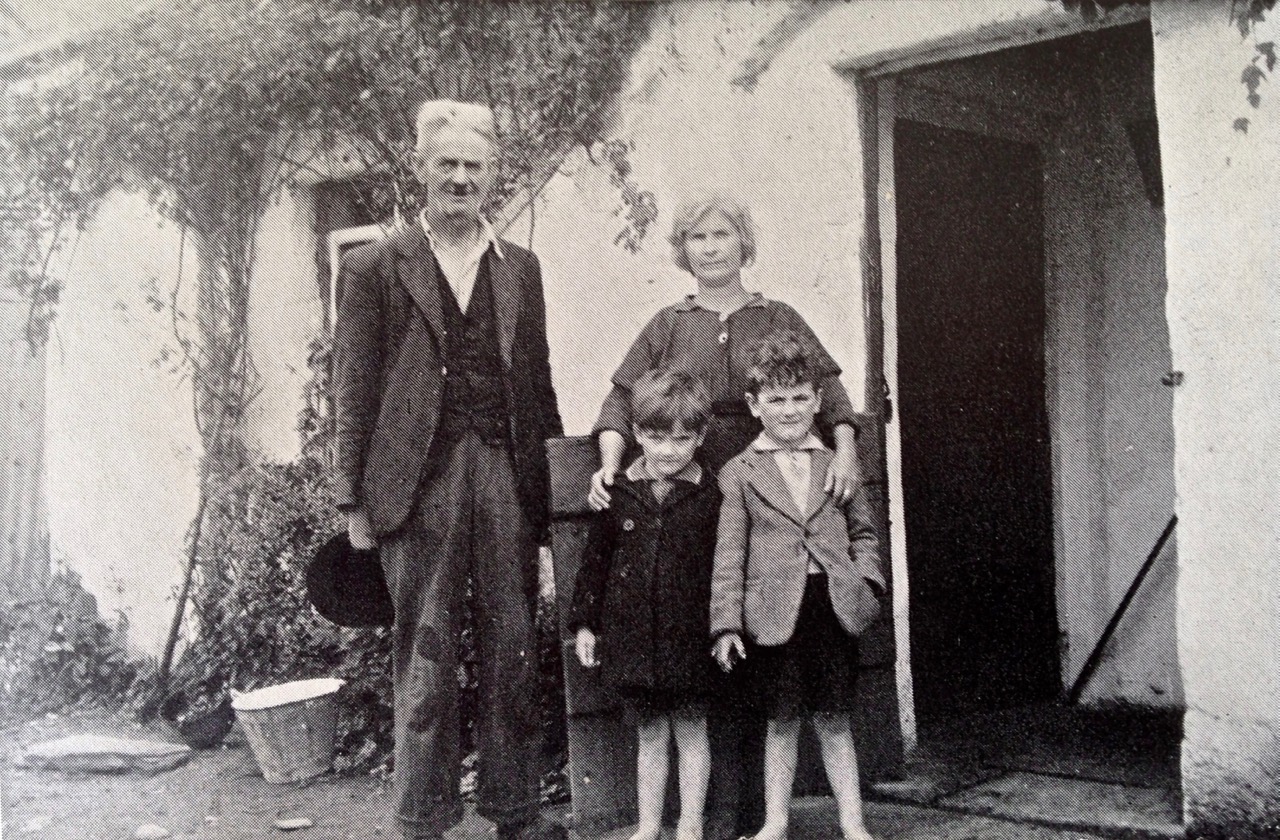

…The canal bore a more and more disused appearance the farther we went westwards, and at Draper’s Bridge lock beyond Abbeyshrule it was obvious that the chamber was rarely filled. Clumps of yellow musk in full blossom were growing out of the chinks in the masonry and looked so beautiful that we were sorry to drown them. The lock-keeper insisted on presenting us with some magnificent new potatoes which he dug from his garden while we were locking through. He refused to accept payment but, noticing Angela’s camera, asked if she would take a picture of himself with the family. She gladly agreed and took a photograph of ‘himself’ with his handsome silver-haired wife and two small boys standing before the half-door of the lock cottage. I hope he was satisfied with the print we sent him…

Angela Rolt’s photograph of the lock-keeper’s family at Draper’s Bridge Lock, Co Longford, taken in 1946

The children in this photograph could well still be alive, in their seventies. Some of the lock cottages on the canals are still lived in by families who have connections with the canals through generations. We were hopeful that we might discover someone at the lock who could point us to these young faces, a lifetime away?

Only ghosts, alas… The cottage is in ruins today. This is unusual, as most of the original lock cottages on the Royal Canal have been retained. There is no sign of why this one has not survived. The Rolts did not name the lock keeper in the book, but I have since discovered that he was Jack Keenaghan. A ghost now with a name, at least.

Lock 39 on the Royal Canal, at Draper’s Bridge. Samuel Draper was Secretary to The Royal Canal Company during the construction of the canal

The Rolts were able to include part of the lower Shannon and Lough Derg in their voyage. They met up with a friend who lived at Kilgarvan, and I was intrigued by this description of a visit to Ballinderry:

…That afternoon our friend and I walked into the nearby village of Ballinderry where we visited Dick Stanley the local baker and proprietor of the village shop…

…In the intervals of baking bread and minding his shop, Dick Stanley makes violins. His art is entirely self taught, he uses the crudest of tools, and he finds and seasons his own materials. He showed us one instrument which he had recently completed and another which was in the course of construction. Though my companion had already told me something of his activities I had expected something which, though praiseworthy enough, bore all the evidence of amateur workmanship. Consequently, even if I had been told nothing I could scarcely have shown more surprise when Dick Stanley put own my hands the beautiful, perfectly finished violin that he had made. Had I not seen the same fine craftsmanship exhibited in the other instrument which was under construction, I doubt if I should have believed that he really had made it. The sound-board was cut from a pinewood beam salvaged from a ruined mill nearby, the body was of sycamore, the pegs of holly wood, while the bridge and frets were of black bog oak dug from the neighbouring bog. None of the instruments he had so far made were exactly the same. He had begun by copying an old fiddle, but he had discovered the improvement and differences in tone which were produced by subtly varying the shape and depth of the sound-box or the thickness of the sound-board. No doubt these critical dimensions are well known and have been standardised by commercial makers but Dick Stanley took nothing for granted. Like all true craftsmen he strove for perfection and expressed a dissatisfaction with his violins which was not false modesty. He admitted, however, that each instrument he had made had a better tone than its predecessor, and his latest one certainly sounded the mellow soul of sweetness as he ran the bow over it. Unfortunately, however, he could not give us an adequate idea of its capabilities because, strange to relate, he was no performer on the violin. He played the flute, using an old finger-stopped instrument with which he often obliged at local gatherings and it was his son who played his fiddles…

…When we had taken our leave of this accomplished craftsman we adjourned to John Tierney’s bar close by, where, to the accompaniment of much village gossip and racy badinage, we fortified ourselves against our walk through the rough weather with pints of porter. Then back to Kilgarvan where we were once more royally entertained despite our protestations that we had surely outstayed our welcome. Never were storm-bound travellers so fortunate in their haven…

We determined that this self-taught fiddle maker was one ghost we were definitely going to track down. Sadly, no photograph of the man or his fiddles is included in the book; nevertheless we felt an exploration was worth making: it would be impossible that no-one in the village remembered the existence of such a craftsman. I even entertained the hope that someone might still have one of his fiddles – and give us a tune!

The ancient bridge at Ballinderry over the Ballyfinboy River, built c 1790

We arrived at the village and admired the old stone bridge over the Ballyfinboy River before walking up through the single street of the settlement. On the right was what had obviously once been the village shop and bar: Elsie Hogan’s. Attached to it was a fine stone residence, resplendent with red painted doors and window surrounds, although now fading.

The fallen shop sign was not a good omen. We peered through the windows and could see empty shelves and an old weighing machine. It felt desolate, but its abandonment – if it was abandoned – could only have been recent. Was this Dick Stanley’s shop? Or might we have been on the wrong track? We pressed on up the village street. There were other houses, and another pub – The Tavern. This also appeared deserted.

No sign of life: the deserted village of Ballinderry was determined not to give up its ghosts

We walked the length of the village. We knocked on doors. We shouted: no shout echoed back. A car repair shop was locked up, in the middle of the afternoon. Houses were obviously occupied but, on that day, no-one was at home. We listened – silence. Yet, did we hear or did we imagine – far off, perhaps on the wind – the thin, ghostly sound of a fiddle being tuned up?

Footnote:

Have a look at the comments below – this story has generated many responses from folks who have memories of this place and these times. One contributor (Les Abbot) sent me a photo of an unfinished fiddle made by Dick Stanley, which I have added below. Les is the great-nephew of Dick Stanley so it’s wonderful to have this direct link with Rolt’s adventures in 1946! Many thanks, Les, for adding colour to this post, and to everyone else who has contributed . . .

The work of Dick Stanley