Finola has been involved in the Ellen Hutchins Festival since it began in 2015 – the 200th anniversary of the death of Ireland’s first female botanist. This year she was asked to help organise and MC an outdoor event, and has had a very busy time – together with her collaborators – leading up to this. On the day – last Friday – I went along to see the culmination of their hard work, and I thought I would share the experience with you.

The weather forecast for that day was atrocious! Heavy rain and thunderstorms were predicted for the duration, and we set out for Ballylickey with some trepidation. However, as is often the case in West Cork, the weather forecasters were confounded. Nevertheless, the Festival team had prepared for all eventualities and we arrived in time to contribute to the setting up of a shelter made from a silk parachute and a number of wooden poles. The transformation of an empty area of lawn in the gardens of Seaview House Hotel into an impressive performance space in a very short time was quite remarkable – and a visual treat – as the swirling mass of silk was tamed by our team, directed by Seán Maskey.

Watching (and, indeed, participating) in this constructional triumph, I was taken back to the days when I lived in Cornwall and followed the escapades of two theatre groups there: Kneehigh Theatre and Footsbarn. Both started out as small troupes of travelling players who took their performance spaces with them and incorporated the action of creating and erecting their transitory auditoria into their shows: all part of the visual entertainment. Both those groups have evolved and travelled far away from their roots, but the evanescent nature of their early shows has stayed with me, to be pleasantly awakened by the happenings at Ballylickey.

To see where Ballylickey fits in to the story of Ellen Hutchins, have a look at Finola’s post from 2015. Ellen was born in 1785 in Ballylickey House and lived much of her short life there. Seaview House – now the Hotel – was built partly in the grounds of the Hutchins family home, so it is a fitting venue for Festival events, as we know that we are following her own footsteps as she became interested in the world of plants and seaweeds which she discovered all around her as she was growing up.

. . . Ellen was a pioneering botanist who specialised in a difficult branch of botany, that of the non-flowering plants or cryptogams. She discovered many plants new to science and made a significant contribution to the understanding of these plants. She was highly respected by her fellow botanists and many named plants after her in recognition of her scientific achievements.In addition to being an outstanding scientist, Ellen was also a talented botanical artist. Botanical drawings serve science in a very important way . . .

Ellenhutchins.com

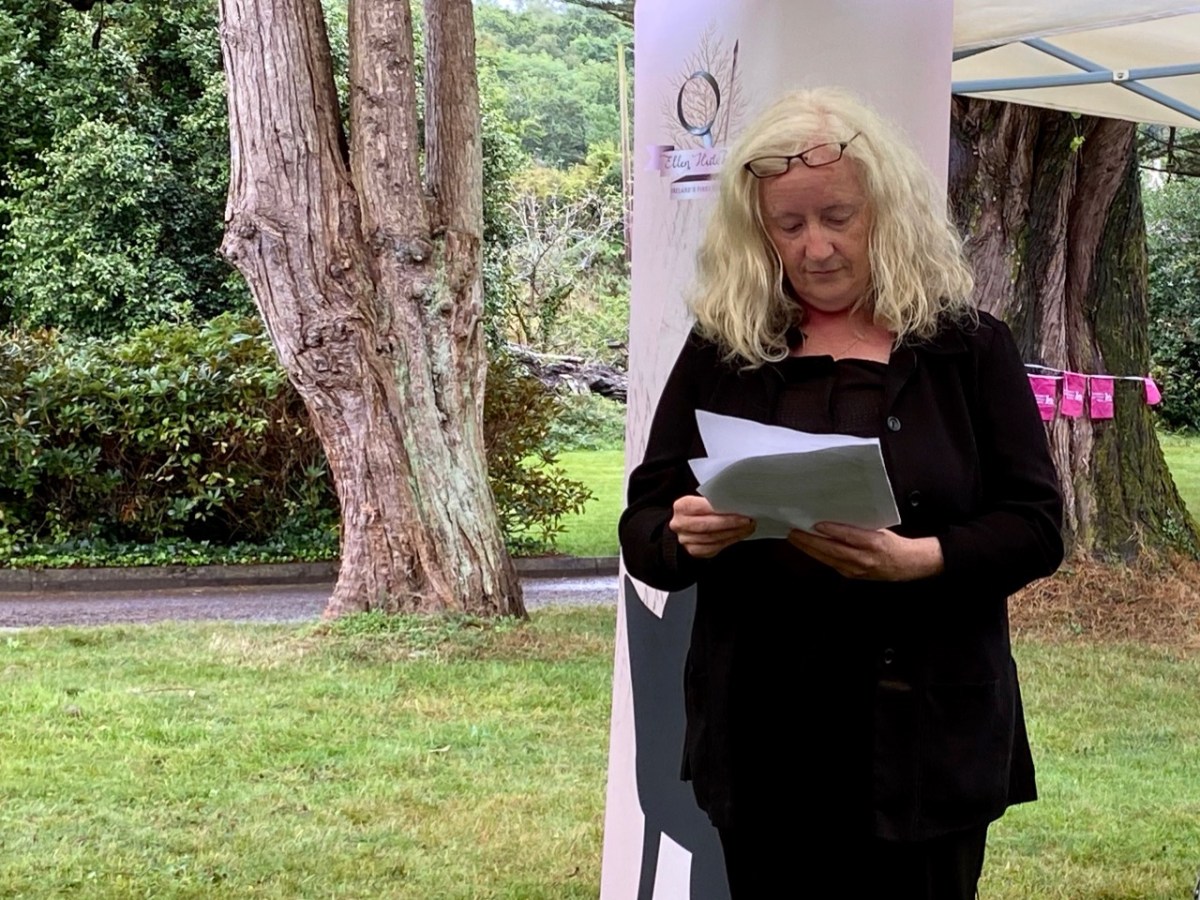

That’s Finola (above) introducing the subject of the day: the correspondence that passed between Ellen and Dawson Turner of Yarmouth, Norfolk, who had become a recognised authority on botany in early 19th century Britain, even though this was always a leisure pursuit: professionally he worked for his father, who was head of Gurney and Turner’s Yarmouth Bank and took over his role on his death. Dawson wrote numerous books on plants and got to know the leading botanists of the day, including Ellen. Amazingly, one hundred and twenty letters between her and Dawson survive. Those from Dawson Turner to Ellen are held by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and those from Ellen to Turner are at Trinity College Cambridge. Friday’s event was a reading of a selection of these letters. On Finola’s right, above, is Karen Minihan, an actor and drama director who lives in Schull: she read the letters from Ellen. Moreover, it was she who selected and organised the extracts – which were the heart of the performance.

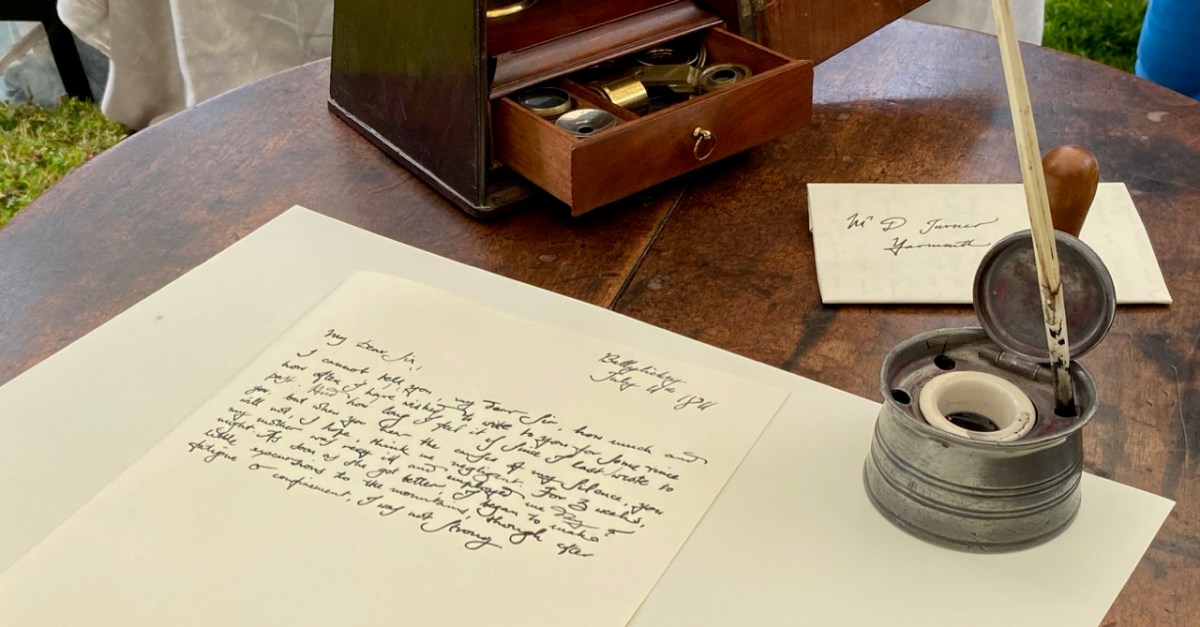

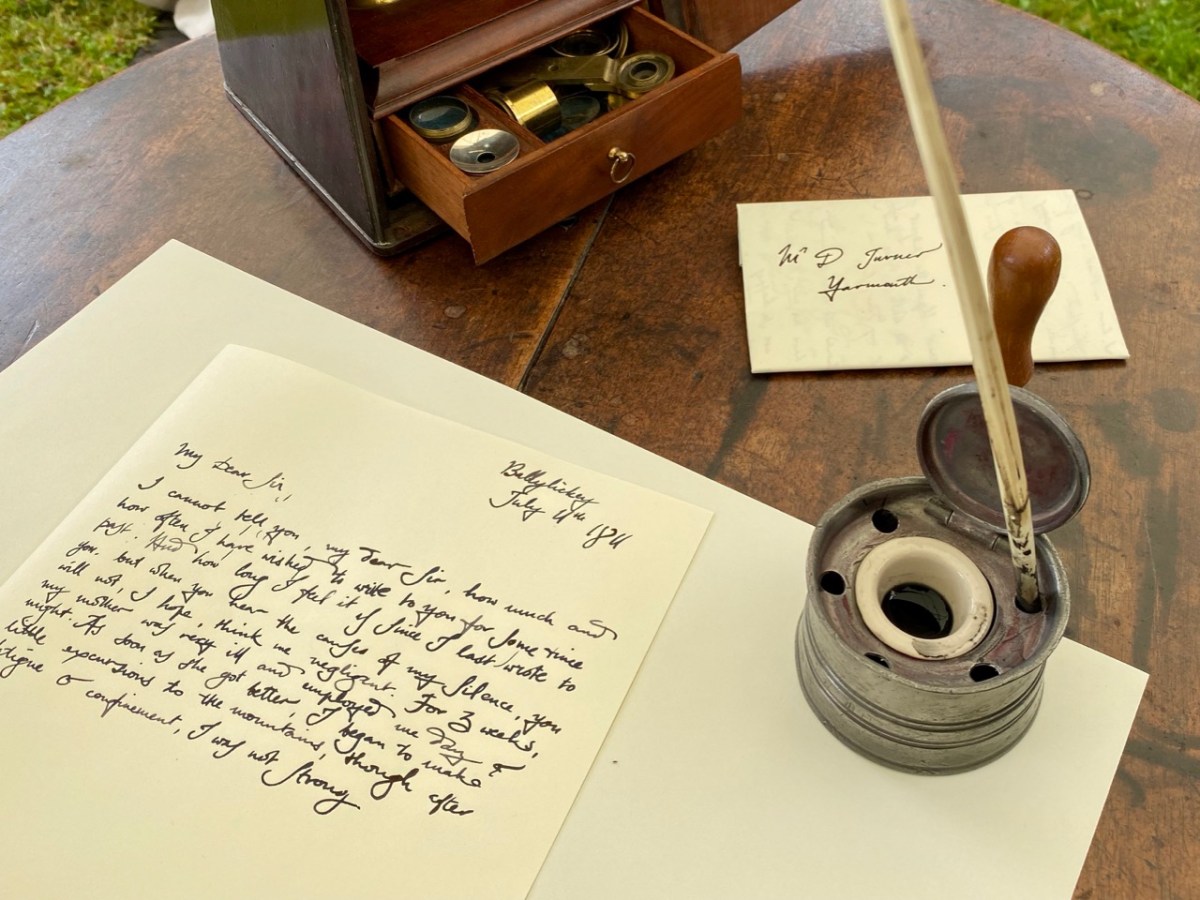

Above are the two other performers: on the right is Mark O’Mahony from Cappaghglass – he is a part-time actor, and here he reads the letters from Dawson. On his right is Carrie O’Flynn. She is a historic re-enactor and researcher: she appeared as Ellen, in authentic period dress, and provided really illuminating interpolations between letter-readings, informing us about the act of letter-writing itself in the early 1800s – the ink and quill pens; the postal service; Ellen’s probable appearance and dress (there are no surviving portraits of her) and the difficulties which Ellen would have had to face in pursuing here chosen interests, especially as she was herself quite frail and was for many years the carer of her own mother. Her achievements in the light of all this are truly remarkable, and Carrie succeeded in bringing this out with her contributions. Below she shows us the brass microscope that Ellen used – an essential item of equipment for her work.

As the reading of the letters progressed it became gradually obvious that a deep friendship was developing between the two botanists, and the language reflected this. Particularly telling (and this was drawn out in the selection of the letters) was the way the missives were framed as time went on. From a simple, almost curt formality in the earliest, we begin to read how their shared interests extended beyond the botanical; they exchange newly discovered poetry; Dawson tells Ellen that he has named his newly-born daughter after her; they imagine how they would like to meet each other and walk their favourite landscapes together. Each sends the other packages containing examples of the plants and seaweeds that preoccupy them, and their greetings at the top and tail of every page become increasingly warmer. We, the audience, open our imaginations as to how a happy fulfilment could ever metamorphose – West Cork and Norfolk are as far apart as any two place could be in early 19th century Britain. Poignantly, we learn that they never met: Ellen – always in poor health – died in 1815 at the age of twenty nine. We can only imagine that Dawson, remote in Norfolk, was desolate.

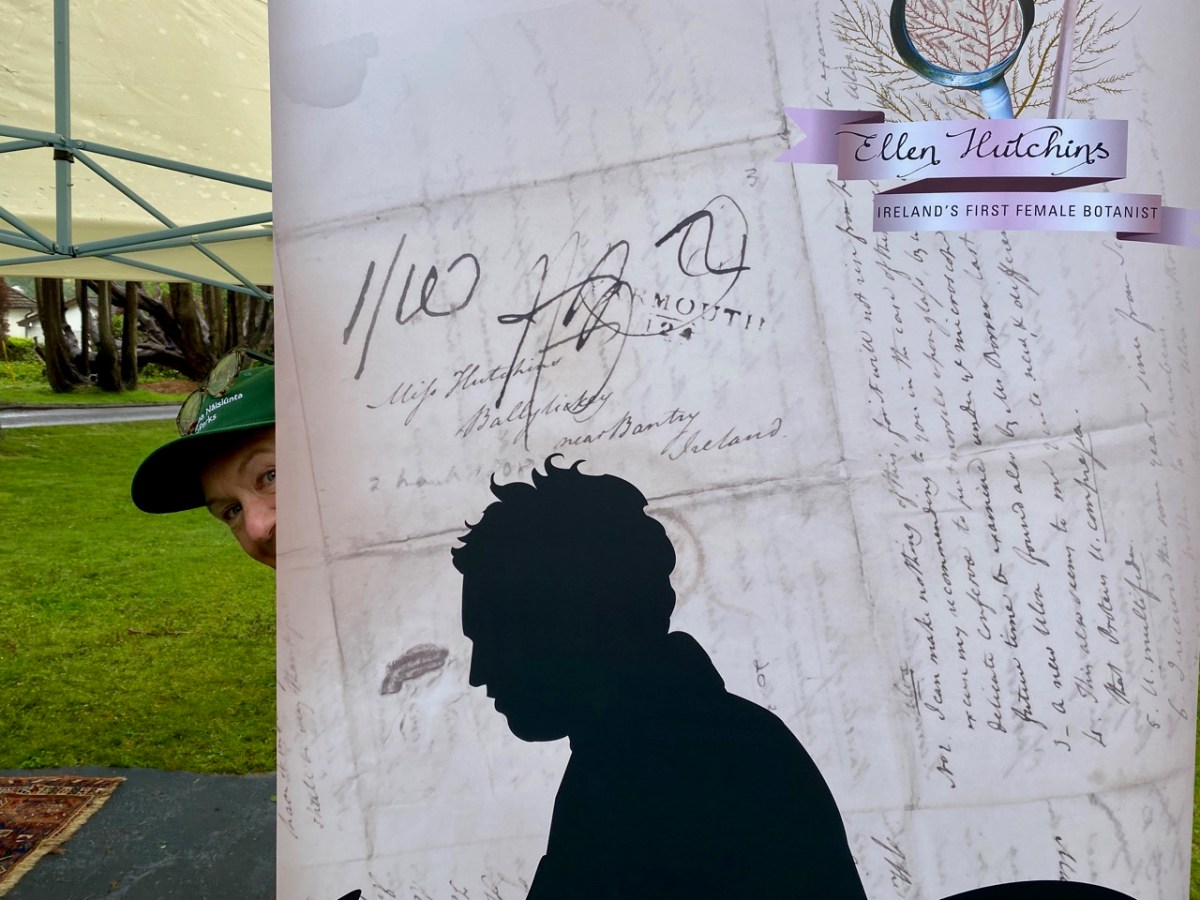

Important to our day – apart from the presenters and actors – were Madeline Hutchins (above – showing us some of Ellen’s drawings of seaweed), great great grand-niece and a co-founder of the Festival; and – behind the scenes but essential – the team, including Clare Heardman, co-founder of the Festival and a Conservation Ranger at the National Parks and Wildlife Service. Here’s Clare in action setting everything up – and running the Festival shop:

We had a further treat in store for us after the show: we were taken on a guided tour of some of the environments which Ellen would have known and explored during her life at Ballylickey. This felt really special, and brought us close, again, to the extraordinary young woman whose short but productive life we now celebrate here in West Cork.

Please note that Ballylickey House today is private property, and visitors should not seek access. There is plenty of the natural environment that Ellen would have been familiar with around Ballylickey and on the shores of Bantry Bay – well worth an exploration. And this link to the Ellen Hutchins Audio Trail is invaluable, especially to anyone who was not able to be at Friday’s event.

Particular thanks, of course, to all who participated – and attended – the event. It was a great success! Thank you to the weather Gods. And many thanks to Seaview House Hotel for providing the venue