We spent a day on ‘The Mountain’. It’s a West Cork location, not too far away from us. The land has a history that touches on many of our interests covered here in Roaringwater Journal – and some of the West Cork people we have written about over the years – so it’s pretty special. We were delighted to be welcomed to it by its present owner, Oliver Farrell: that’s himself, in the pic below. You have met him before, here. Thank you, Oliver, for allowing us to experience this special site, and for letting us put out this post about it.

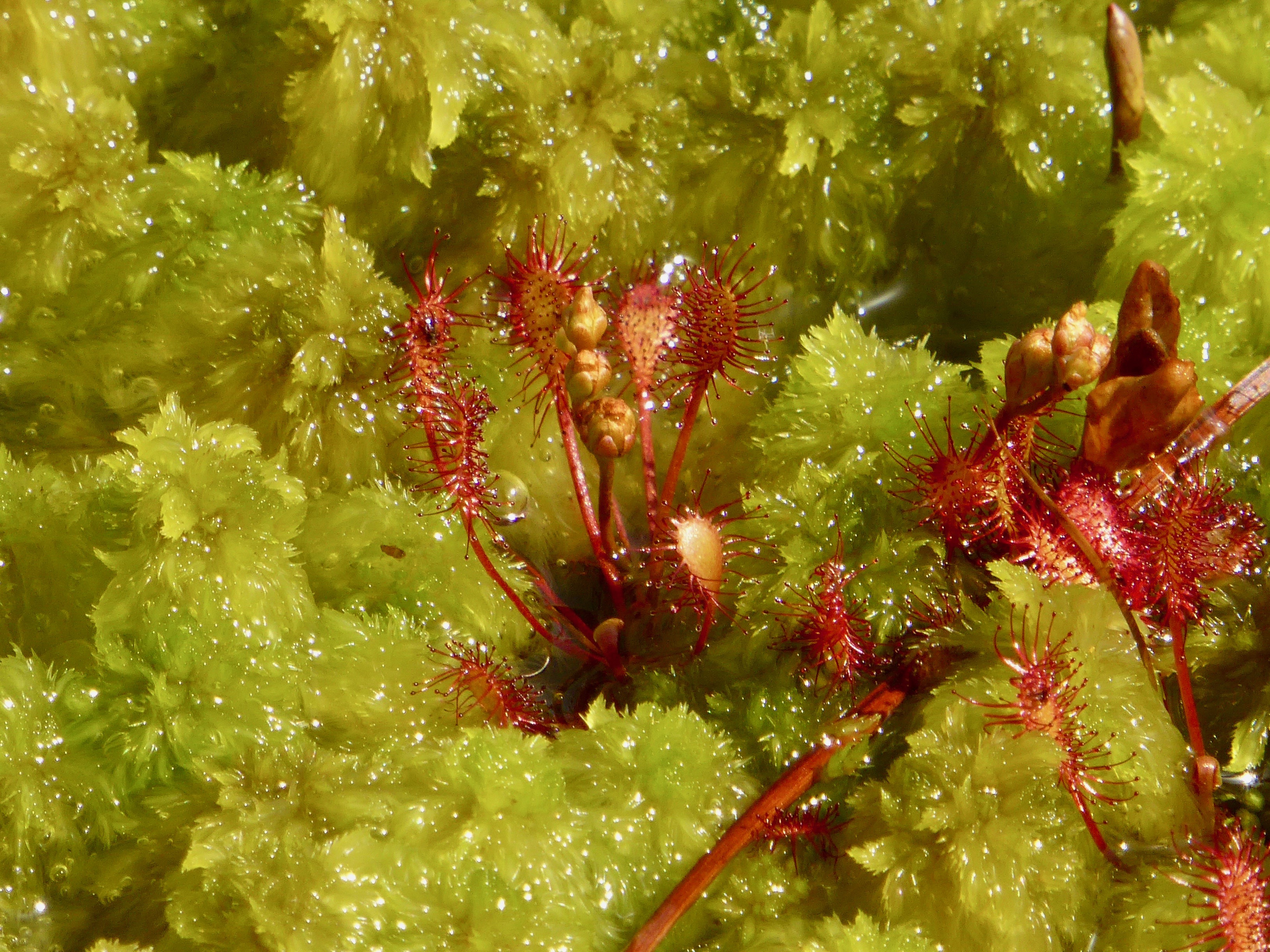

Previously, the 70 acre ‘Mountain’ site was owned by the Wrights – Lynne and Ian (above): you saw them in the 2022 Ballydehob Arts Museum exhibition, here. When they purchased it – in 1997 – it was rough pasture and bog. They aimed to develop an environmentally and economically sustainable forest using existing grants, and successfully challenged the decision of the Forest Service (through the EU) to only grant aid the planting of alien conifers. They set about transforming it: they had a vision of a ‘pure’ West Cork landscape supporting an ecosystem of native species. Now – many years later – it’s possible to see that the Wrights’ vision was fully justified – and realised. Today Oliver is undertaking essential maintenance work, and is committed to expanding on the inherent sustainable qualities that the site embodies. In fact, ‘The Mountain’ is largely in excellent environmental order.

Interestingly, Ian told us that when they made the decision to buy the site they had only seen it under cloud: the spectacular view wasn’t revealed until later on. We were fortunate on the day of our visit to see the full panorama of Roaringwater Bay stretched out before us.

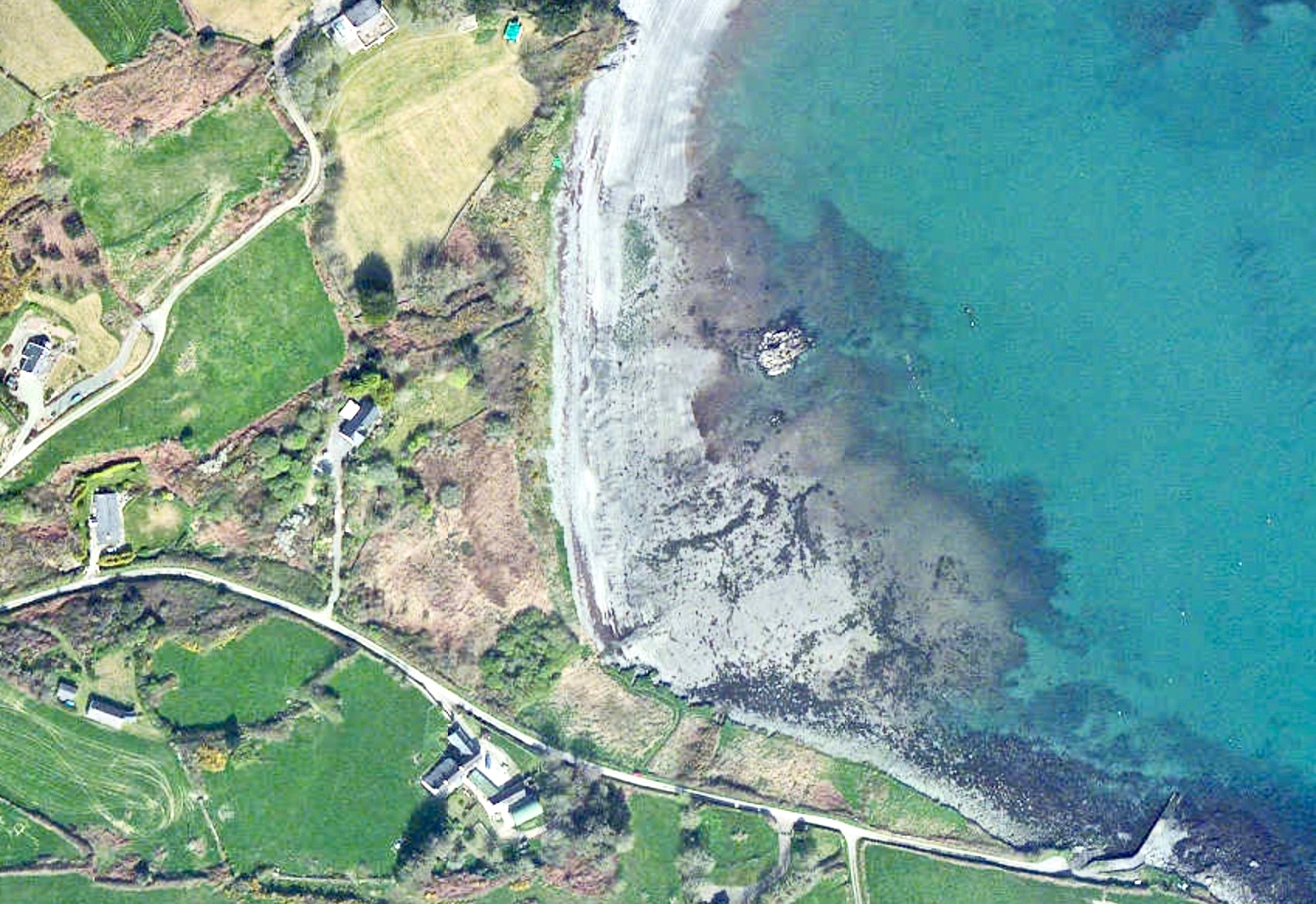

This dramatic view towards Mount Gabriel is a reward for climbing ‘The Mountain’. The ground was waterlogged on the day of our visit as this autumn has been a time of relentless rainfall, but always interspersed with brief dry patches: it’s great to be out to catch these. Springs rise on the high ground here, and I’m working out that they either feed the Roaringwater River – the water that gives its name to the whole Bay and islands that are central to our view from up here in Nead an Iolair, or another of the many streams that drain the West Cork hills below us.

Oliver stands above one of the spring outlets that form the infant waterway (top), while the stream matures as it flows on down through his land (lower). Below – Oliver and Finola inspect one of the lakes which has been created within the site.

At one stage in his life Ian researched, developed and introduced the building of low–tech ferro–cement boats as a cottage industry on Lake Malawi to help address the problem of unsustainable fishing practices there. At the ‘Mountain’ site he experimented with ferro-cement as a material for establishing a well blended-in shelter and store.

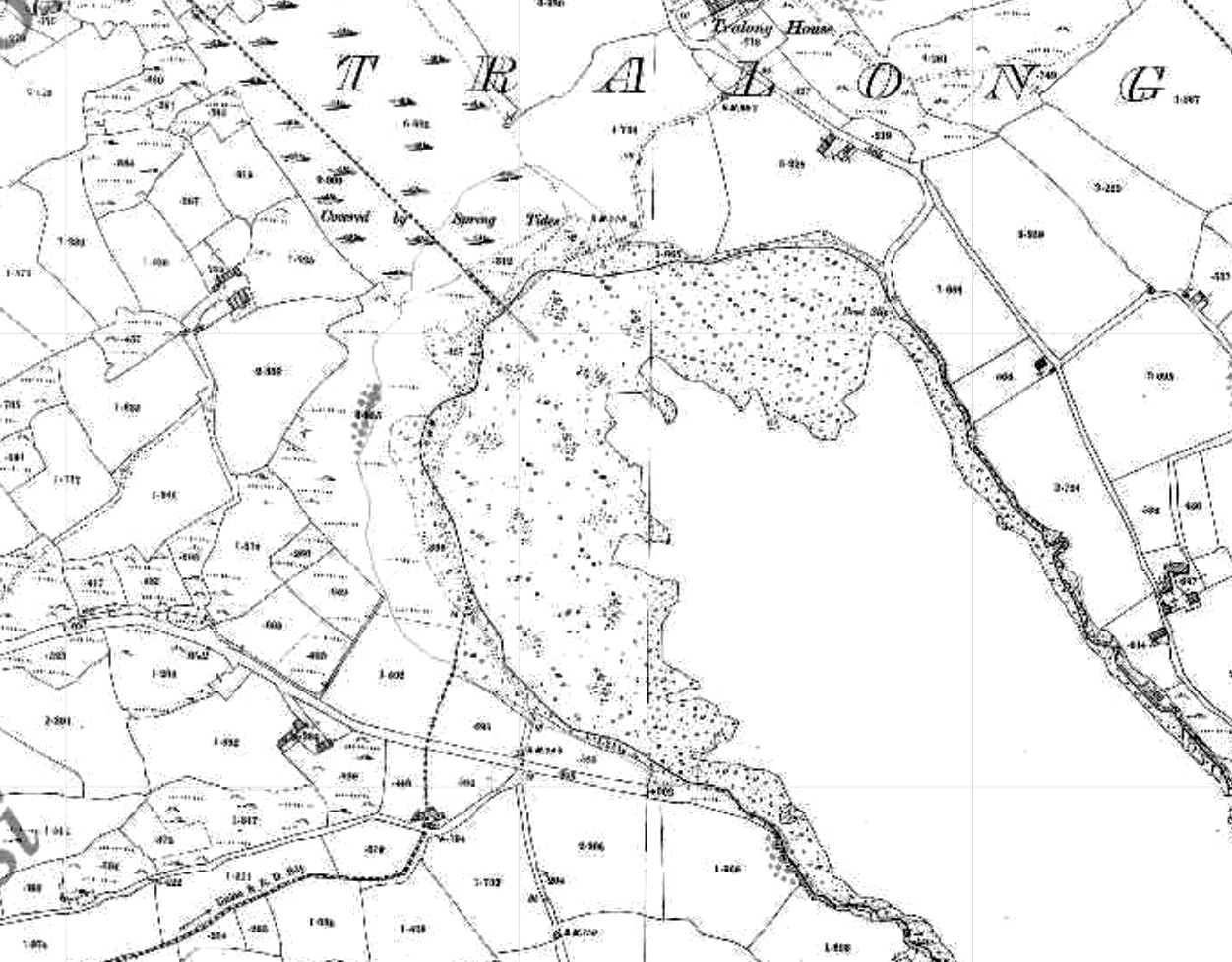

Straddling two townlands, ‘The Mountain’ is an impressive example of how an area of West Cork wilderness has been perfectly moulded into its natural setting. It is an out of the ordinary place which demands exploration.

I’ll be visiting the site, and writing about it more in the future. Oliver will be keen to allow access: keep watching this space.