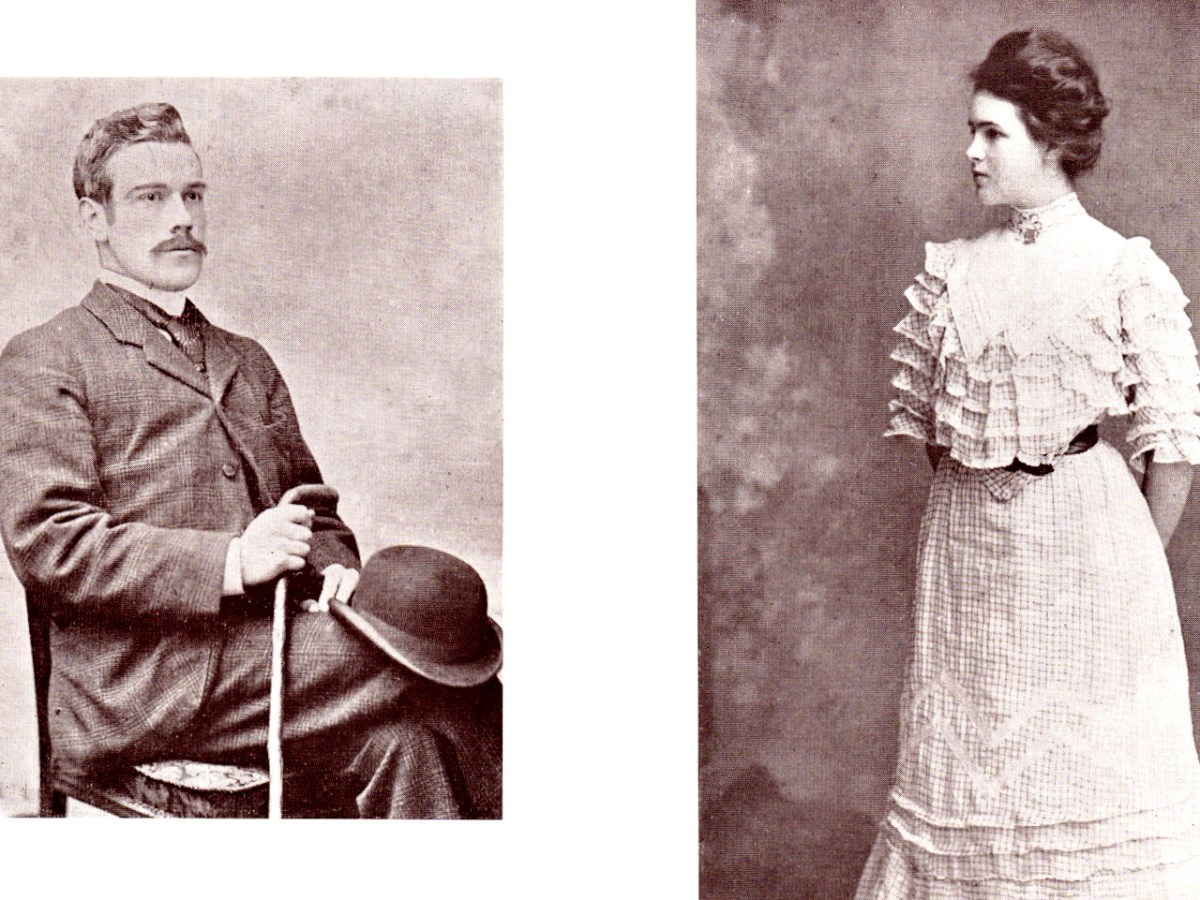

Back to Ireland of the Welcomes and this time to the March-April issue of 1971. This was a special issue, largely devoted to John Millington Synge, born April 16th, 1871, which means that next Friday is the 150th anniversary of his birth. These two photographs from this issue show Synge and the beautiful Abbey actor to whom he was engaged, Molly Allgood. Alas, JM died far too young, at 38, and Molly went on to lead a longer but unhappy life.

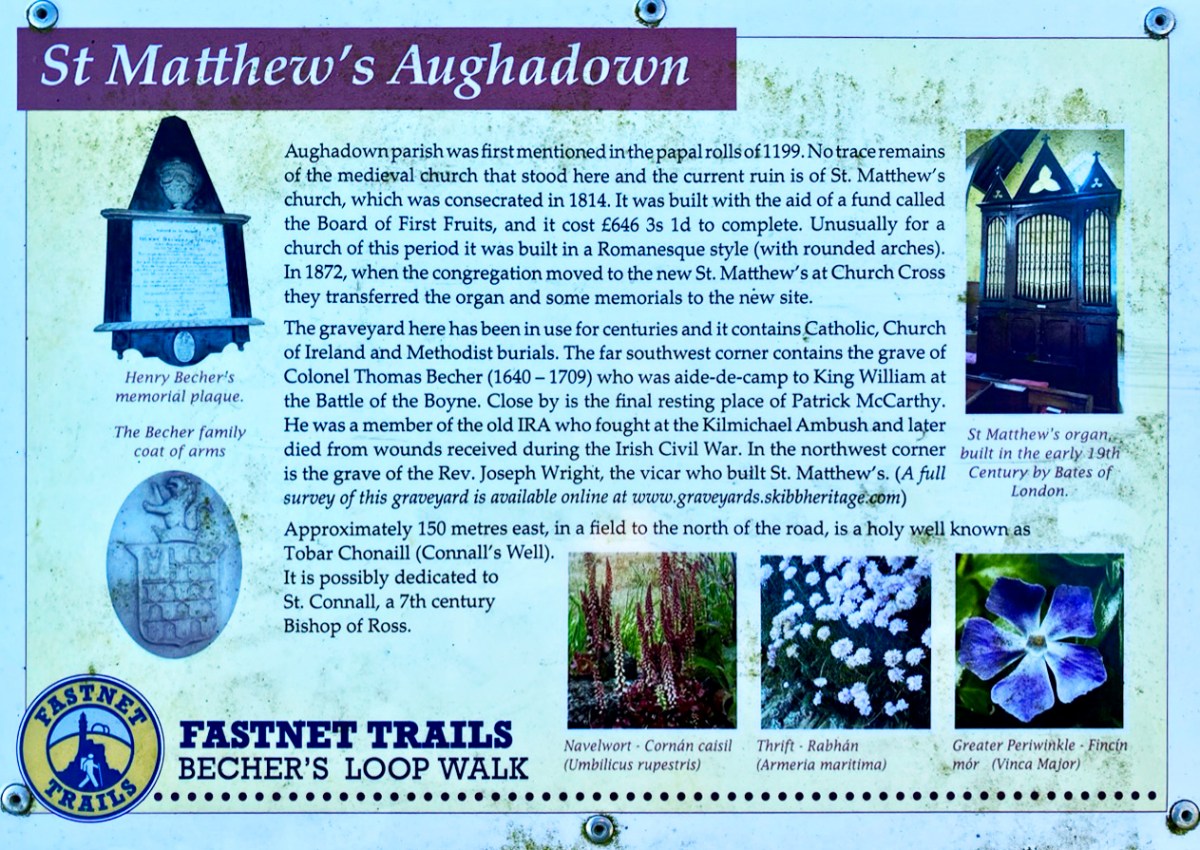

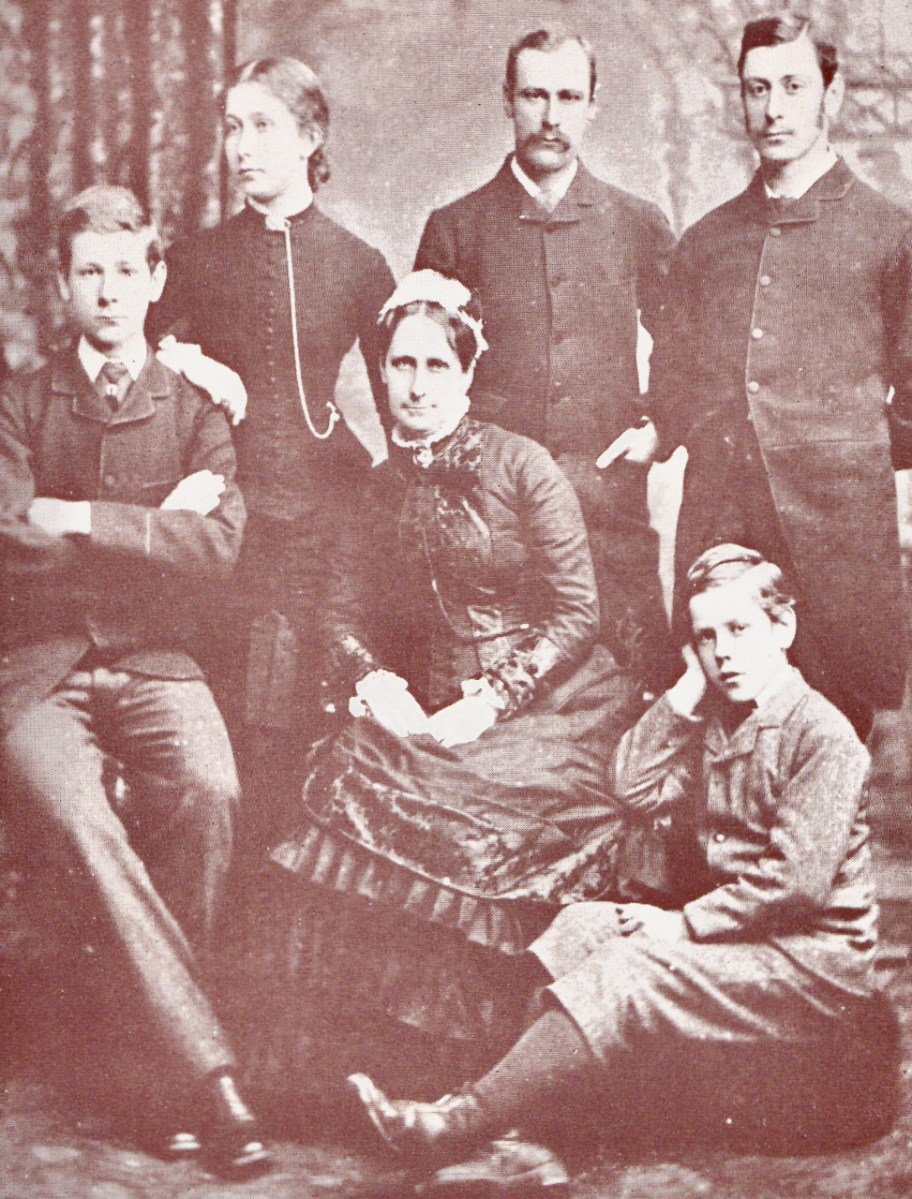

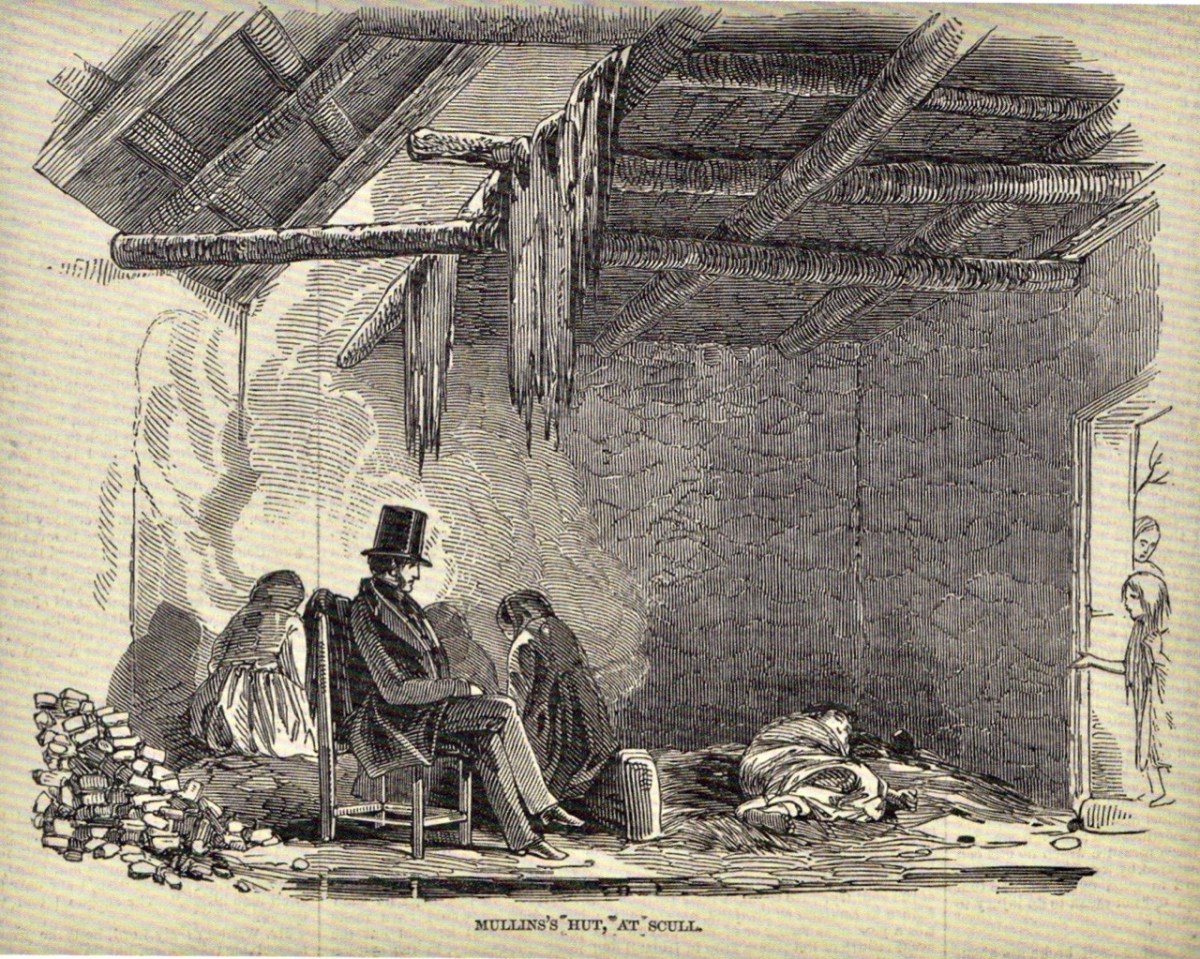

There’s a special connection to West Cork too – Synge’s mother, Catherine but known as Kathleen, was the daughter of the Rev Robert Trail, Rector of Schull. She is shown above with her children – JM is bottom right. I have written about the various roles her father played in this area. During the Tithe Wars he railed against all protests, declaring that he “waged war against Popery and its thousand forms of wickedness”. He saw an outbreak of cholera after a huge rally as God’s vengeance on this who would deprive him of his income. He tried his hand at mining and established a considerable workings at Dhurode, the remains of which can still be seen – see Two Mines are Better Than One. It was doing well when interrupted by the Famine. Finally, during the Famine, his better nature won out and he worked tirelessly to alleviate distress. He died of famine fever in Black ’47, universally mourned and honoured for his efforts to inform the public about the dire situation and to feed the starving people all around him. That’s Traill below in one of James Mahony’s sketches for the Illustrated London News – he had led Mahony to Mullins hut so he could witness and capture first hand the desolation, disease and despair.

That was in 1847 and Kathleen would have been 11. There is a contemporary account of how hard the whole Traill family were working to fill the soup pots, how difficult was the ceaseless onslaught of begging, how dangerous the fever-filled air. Her mother fled Schull as soon as she could after Robert’s death – she was later sent a bill for damage to the rectory caused by building a soup kitchen! Kathleen married a barrister, John Hatch Synge, and Edmund John Millington was their youngest child. Kathleen found solace from the trauma of her early experiences in her father’s stern fundamentalist faith – a faith that never wavered although it brought her into conflict with JM. Interestingly, that conflict did not destroy their mutual love for each other, and Kathleen (although looking stern in the photograph below) has been described as kind and generous.

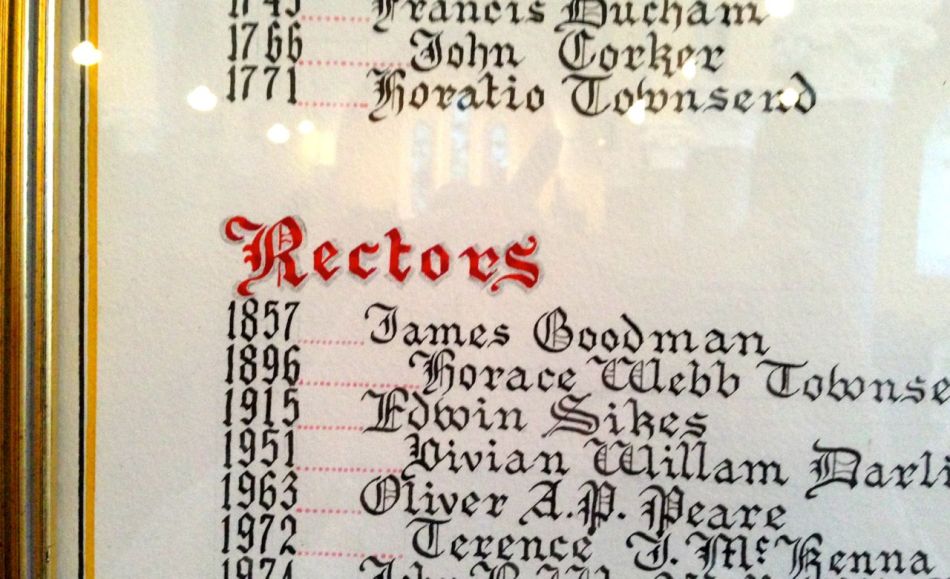

JM grew up to be one of Ireland’s foremost dramatists and the writer of a unique and inventive form of English that set out to capture the idiom and cadence of Irish. And here’s where our second West Cork connection comes in – his Irish teacher in Trinity was none other than our own Canon Goodman (below), who spent half of each year in his parish of Abbeystrewry in Skibbereen and the other half in Dublin teaching Irish. He had no more committed or enthusiastic student than JM.

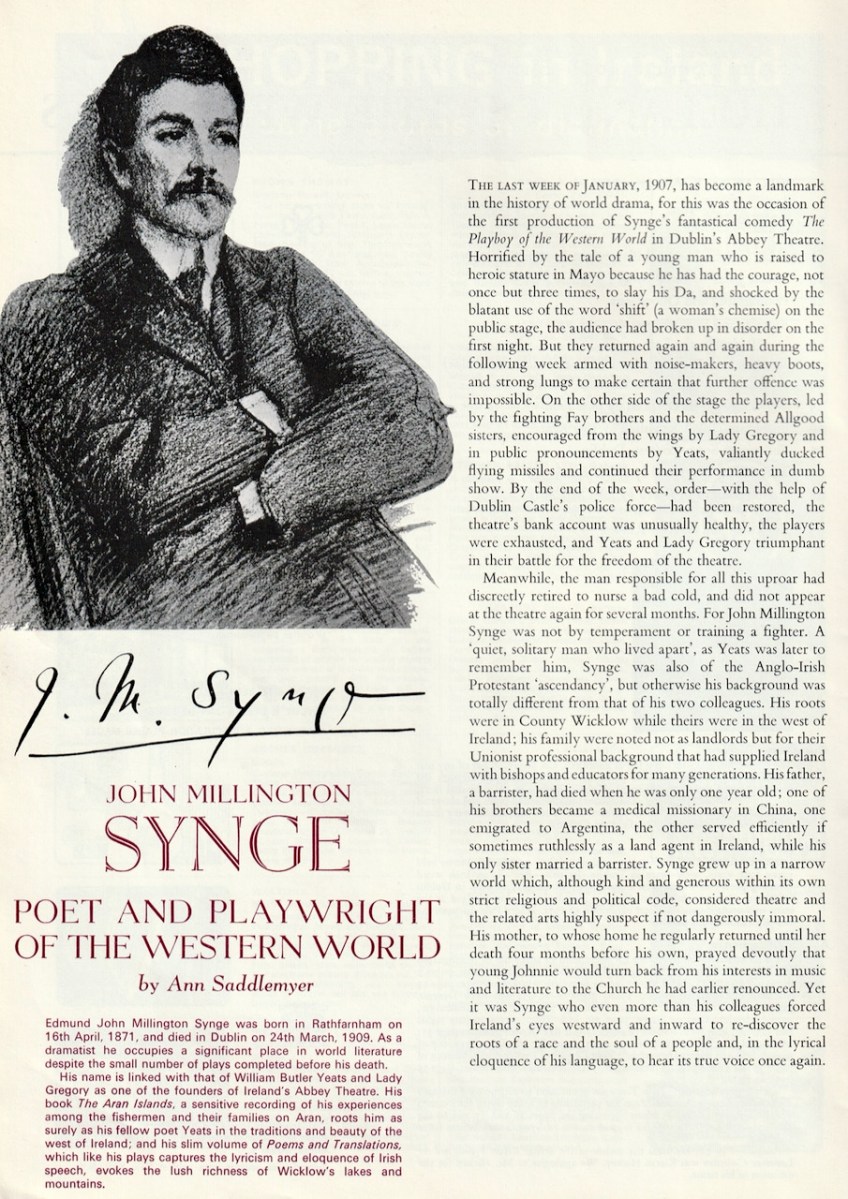

For an excellent summary of the life and work of JM Synge I recommend you to the essay by Declan Kiberd in the newly-available-online Dictionary of Irish Biography. In this issue of Ireland of the Welcomes the major essay on Synge is by the distinguished Canadian Academic Ann Saddlemyer. Saddlemyer is now 90, an elected member of the Royal Irish Academy and a long-recognised expert on Synge, WB Yeats and the history of Irish theatre.

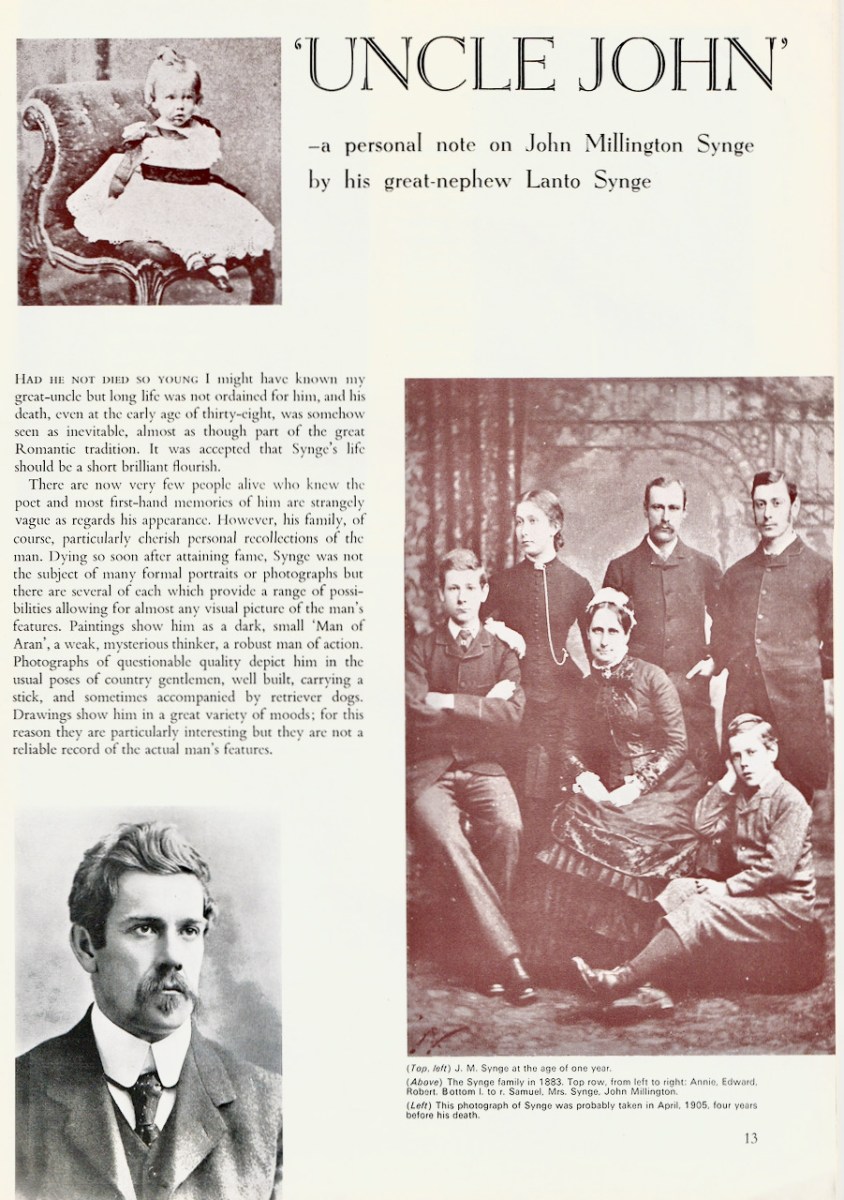

Another charming piece is by JM’s great-nephew, Lanto Synge, a fine arts and antique consultant, recently retired. His essay tells the stories that have come down through the family, including the great religious divide. He paints a portrait of a shy, nervous, intensely musical and engaging man, travelling and studying wherever he went, philosophically attuned to modern thought while immersed in an appreciation of an ancient language and way of life.

The issue contains several extracts from Synge’s plays, poetry and prose, each one illustrated by photographs or drawings.* One thing I hadn’t realised is that Synge was an early photographer. Although some of his photos are are reproduced in this article (two examples below), you can see better images at Ricorso. They show he had an ethnographer’s eye and an interest in the everyday lived experience of his subjects, such as the man threshing by hand and the two women spinning.

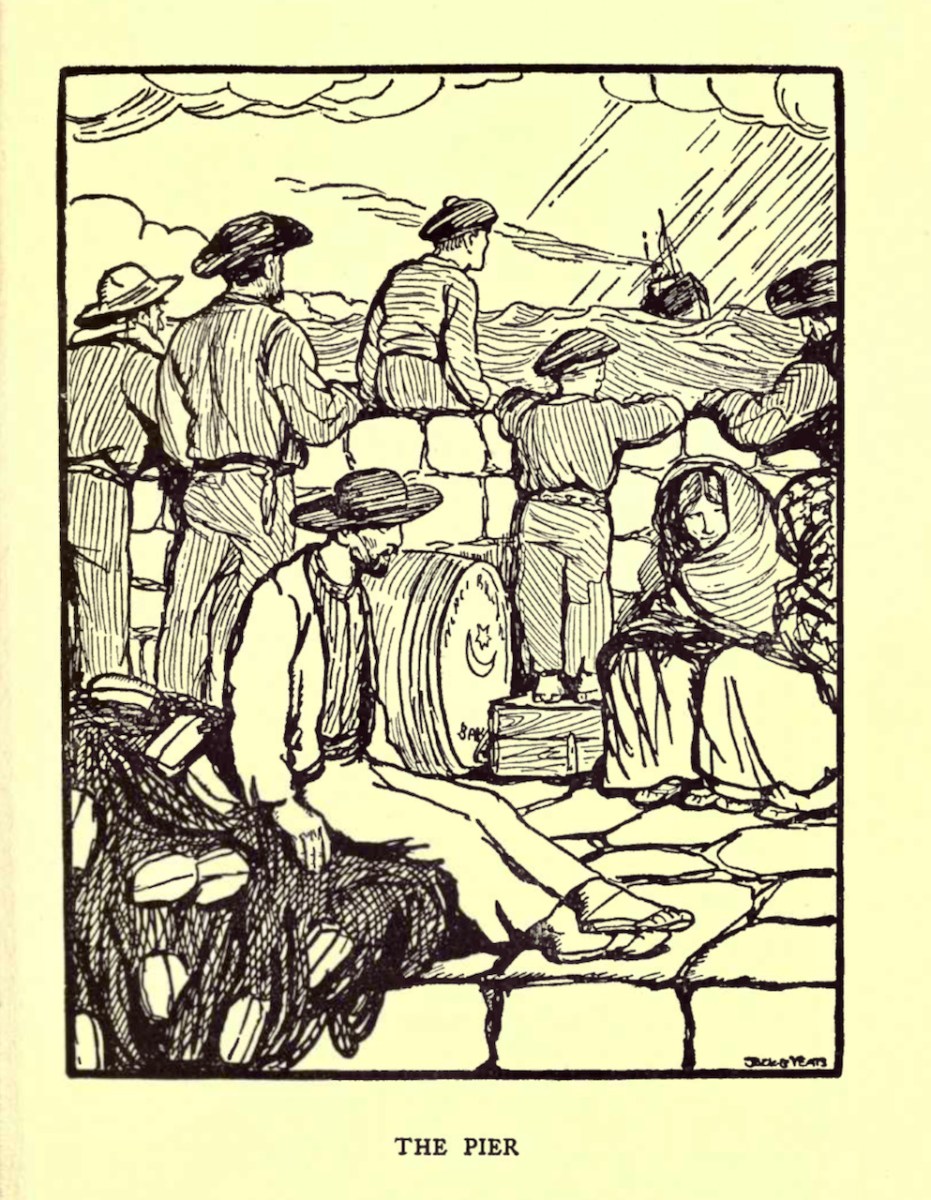

One of his great friends was Jack B Yeats and they worked collaboratively on several projects. Yeats illustrated his book on the Aran Islands (downloadable from archive.org – a site that is surely the greatest boon to researchers like us!). The two pictures below are from that source rather than the article. Synge and Yeats were of one mind, it seems, in what they chose to focus on.

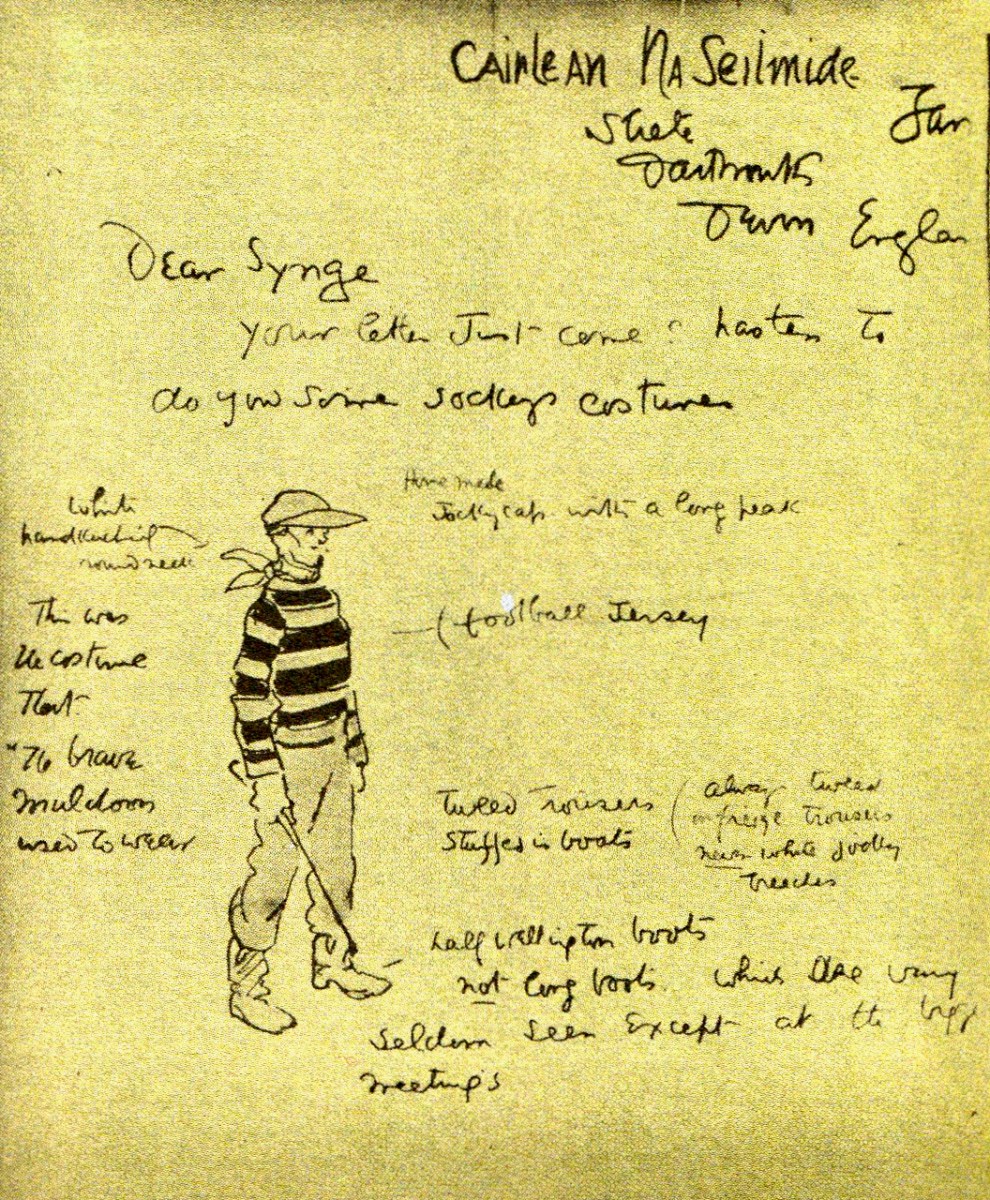

But Jack B Yeats did more than illustrate The Aran Islands – he produced drawings for Synge’s three-act masterpiece, The Playboy of the Western World. This appears to have been an iterative process. We see a letter from Yeats to Synge, advising on the outfit a jockey might wear in the West of Ireland.

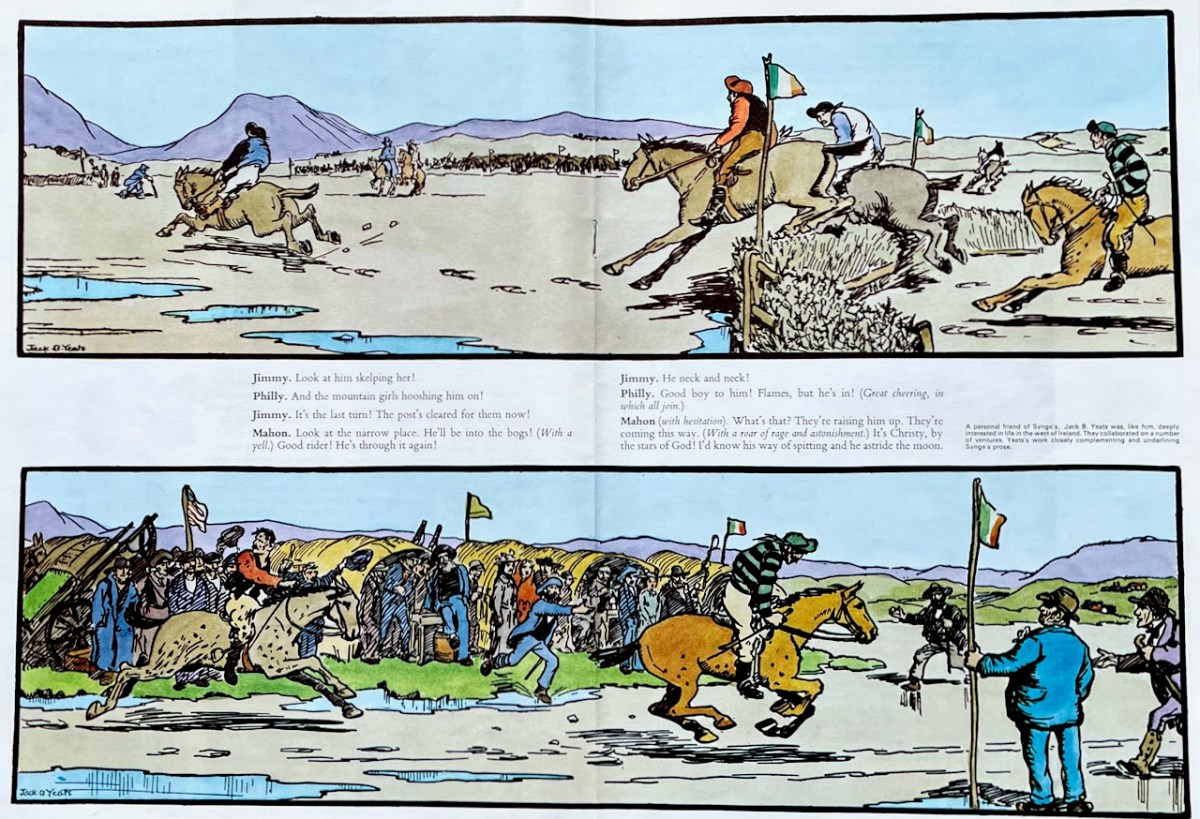

The finished illustrations are wonderful – this subject gave Yeats great scope to indulge his love of horses and horse racing.

Two of the horse racing sequences occupy the centrefold of the issue. It is obvious that both Synge and Yeats are intimately familiar with, and relish, this kind of occasion in the West of Ireland.

This issue of Ireland of the Welcomes does contain a couple of other articles, but I will leave it there, since the bulk of it is devoted to Synge and it is good to focus on and celebrate him on such an auspicious anniversary.