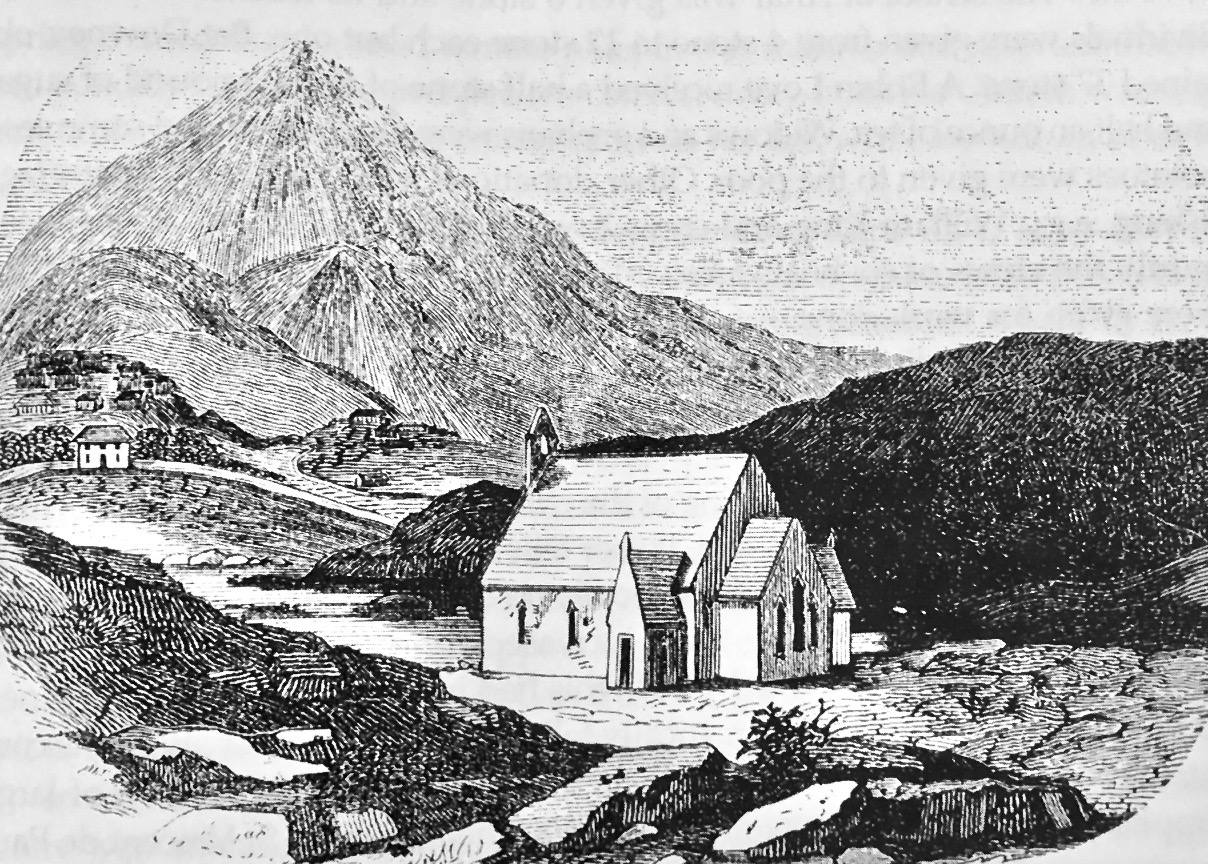

It’s an unassuming little building, quaintly situated on a piece of rocky land by the sea just west of Schull on the Mizen Peninsula. Nothing in its appearance now hints at its contentious past, although it certainly manages to look very attractive in this watercolour by Paul Farmiloe.

The church is often described as ‘Celtic’, ‘Romanesque’, or ‘based on an ancient Irish model’. This is curious as it has no precedents that I know of in ancient Irish architecture, except perhaps for the small triangular window arches, such as this one (above) from St Flannan’s Oratory in Co Clare.

The interior is quite beautiful in its simplicity and in the repeated use of the motif of an unusual and striking stepped-triangular design for the chancel arch, the windows and the doors.

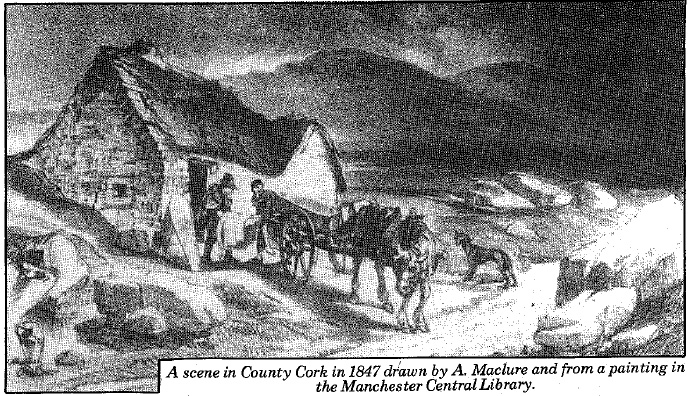

The name, perhaps, seems unusual – in fact it is the only Church of Ireland building named in Irish, Teampall na mBocht, the Church of the Poor. Yet this one small building, constructed at the height of the famine of 1845 to 50 was once the focus of a firestorm of accusation and counter-accusation.

The story of Teampall na mBocht is central to the history in Ireland of what is known as souperism. To take the soup or to be a souper is the worst thing you can accuse a person of – it means to sell out your principles for worldly gain and is based on ugly incidents during the Great Hunger where Church of Ireland and Methodist Ministers were accused of offering food in exchange for conversion. Souper was originally used to describe the person offering the soup, but in modern parlance it is usually reserved for those taking it. As we shall see, accusations of souperism were levelled in both directions – by and against the Catholic Church – during this period.

The stained glass windows were a later addition. The East, Ascension window is by Joshua Clarke and executed in 1919. Although Harry Clarke was working with his father at this time there is no evidence that he had a hand in this window, which is not in his style. However, Harry learned much in his father’s studio that is evident in this window, including attention to detail, the use of good glass and sumptuous colour

The term ‘famine’ is in itself controversial, since many assert that it cannot be used except where food sources have dried up. They point out that food continued to be grown and exported during the period of the potato blight. I use the word here, along with the term ‘Great Hunger’ since it is the terminology used in most of the sources I consulted. Also, as will be seen, it accurately describes the situation in Kilmoe during this period, in which there was literally no local food to be found by any means.

The above image was retrieved here

The story is a complex one, and as I have tried to navigate it my chief source has been the magnificent volume Famine in West Cork: The Mizen Peninsula, Land and People 1800-1852 by Patrick Hickey. The book is now out of print but available through the internet. Fr Patrick Hickey, or Father Paddy as he is known locally, published his study in 2002, a monumental work of unparalleled erudition and thorough research. Himself a Catholic priest, his study is even-handed and fair, giving credit where it is due on all sides, and filling in the vital historical background to present a picture of these remote communities and the religious, educational, economic and social conditions prevalent at the time.

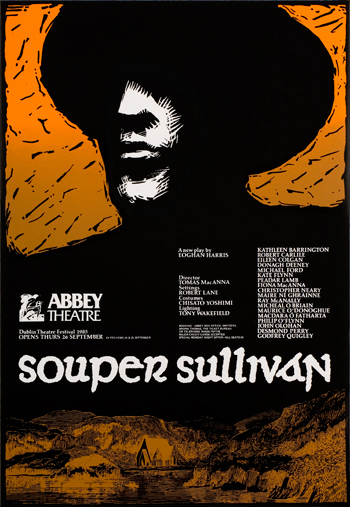

Others too have studied this little church, including the journalist and writer Eoghan Harris who based the action of his play Souper Sullivan on the events I will describe. Harris is himself not shy of controversy and has long waged a lonely battle against what he sees as the black-and-white victim-narrative version of Irish history. He poses the question – “So why is the heroic story of the spalpeens of Teampul na mBocht not a cherished part of Skibbereen’s Famine memory?”

In this multi-part post, I hope to address Harris’s question, and tell a story that captures this terrible time in all its complexity. But first – the bare facts.

In 1848, at the height of the famine in West Cork, Rev William Allen Fisher, using funds raised chiefly in England, employed starving locals to build a Church of Ireland (Protestant) church in his parish of Kilmoe. In doing so, he surely saved several hundred from starvation. His admiring son-in-law, none other than Standish O’Grady, described his devotion to the poor of his parish and his heroic efforts on their behalf and pronounced him a Saint. The Catholic Church, on the other hand, accused him of buying souls with food and held him up as the worst example of Souperism. (There’s a slightly fuller version in Robert’s post Another Grand Day Out on the Fastnet Trails.)

And yet – it had all started out well enough, with the Rev Fisher and Fr O’Sullivan the local parish priest working together to alleviate the awful situation. How did it all go so wrong? Who were the actors at the heart of the drama? What was the prevailing social and religious environment in the district at the time? What lens can we use to view this part of our past?

Stay tuned…

This link will take you to the complete series, Part 1 to Part 7