As might be obvious by now, I am having fun playing around with DALL·E, the image-generating arm of ChatGPT. In its own words, DALL·E 2 is an AI system that can create realistic images and art from a description in natural language. I am experimenting by asking DALL·E to serve me up illustrations of St Brigid, and learning, in the process what it can do well, and where it seems to lack, well, a brain. On the whole it’s very impressive indeed, but also quite unreliable. Here are my requests and what I got in response – and notice how polite we are! Note also that DALL·E often responds with two images, but I usually only choose one of them to reproduce here.

ME: Can you design a Saint Brigid image for me, in the style of Harry Clarke, please?

DALL·E I can create an image inspired by the style of Harry Clarke, which would incorporate detailed, intricate patterns, rich colors, and a unique, stylized approach. Since Harry Clarke’s most recent work was after 1912, I’ll focus on aspects of his style like detailed stained glass art, with a gothic and Art Nouveau influence. For Saint Brigid, would you like her depicted in a specific setting or with certain attributes? Also, would you prefer a full-body portrait or a more focused image?

ME: Full body, with a lamp, oak leaves and a fox

DALL·E: Here are two images of Saint Brigid created in a style inspired by Harry Clarke. They feature her with a lamp, oak leaves, and a fox, all depicted in a detailed and vibrant manner characteristic of Clarke’s influence. Feel free to select the one that best suits your needs.

AI is trained by scanning all the images that it can consume on the internet, and obviously Harry Clarke has not yet been studied in detail by DALL·E – this image is nowhere close to his style. I award some marks for getting the attributes in there, and the early 20th century period art nouveau styling. What on earth is that caption, though, and what’s going on in her gown? On the whole, despite the halo, this illustration leans more to the Celtic Goddess end of the spectrum, and as you know I am not sympathetic to that version of her. Let me explain what I mean by that – there may well have been a Pagan or Pre-Christian Goddess figure with a name similar (we have Brigantia from Roman writings and the daughter of the Dagda from Irish mythology) but there is good evidence that the Saint Brigid we are talking about here was a real woman. A recent paper by Elva Johnston of UCD lays out the argument very well. Johnston says:

Brigit of Kildare is the first Irish saint to be celebrated in detail by Irish writers. Her cult enjoyed great depth and popularity. Nevertheless, Brigit’s very existence has been doubted; she has been recast as a pre-Christian goddess despite an overwhelming disparity in evidence . . . Brigit has been treated differently to Irish male saints, becoming a secondary character in her own biographies, reductively overshadowed by a barely attested goddess. It is time for a revitalised appreciation of Brigit as an actual woman, depicted by her first hagiographers as pushing against the grain of an elitist and patriarchal society.

Making St Brigit real in the early middle ages

Elva Johnston

Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Advance Access,

I highly recommend this paper for anyone interested in learning more about the actual historicity. I also asked for a version of St Brigid in the style of a Rosetti Pre-Raphaelite painting and here’s what I got. Once again, although a beautiful depiction, it would be easier to see a Pagan Goddess reflection in this illustration than a devout saint. I decided to be more directive.

ME: can you create one that looks more like renaissance painting, depicting Brigid as a nun, with a church in the background

DALL·E: Certainly! For a Renaissance-style painting of Saint Brigid, I’ll focus on the distinct characteristics of that era: realistic proportions, a harmonious composition, and a depth of emotion and spirituality often found in Renaissance art. Saint Brigid will be depicted as a nun, with her habit and serene expression. The background will feature a church, possibly with architectural details reflective of the period, adding to the authenticity of the Renaissance style.

Here are two images of Saint Brigid depicted in the style of a Renaissance painting. In each image, she is portrayed as a nun, with a church in the background, capturing the essence of Renaissance artistry. Feel free to select the one that resonates most with your vision.

ME: The first one is a good start. Perhaps she could be older, and with her attributes, oak leaves, a lamp and a fox. Instead of the church, can you reproduce this St Brigid with only an Irish round tower in the background?

DALL·E: I’m glad to hear the first image is a good starting point. To modify it according to your suggestions, I’ll create a new image where Saint Brigid appears older, reflecting more maturity and wisdom. This change can be subtly conveyed through her facial features and expression, akin to the way a seasoned tree shows its age through deeper grooves in its bark.

Additionally, I’ll ensure her attributes are prominently featured. The oak leaves, symbolizing strength and endurance, can be woven into her attire or held in her hands, like leaves carried by a gentle breeze. The lamp, a beacon of light and guidance, could be in her other hand, casting a soft, illuminating glow. Lastly, the fox, a symbol of cleverness and adaptability, will be included, perhaps sitting loyally by her side or in a protective stance, akin to a faithful companion.

Hmmm – that round tower looks like something Rapunzel might be hiding out in. And – what on earth is that thing in the glass object? Love the fox and the lamp, though – and that little crucifix she’s wearing. She really does look like a wise old nun. In fact, I think she taught me.

ME: The last one is perfect – just one more modification, please, can you incorporate some Celtic interlacing or knotwork into the design

DALL·E: Absolutely! Adding Celtic interlacing or knotwork will infuse the image with a rich layer of cultural depth, typical of Irish art. This intricate detailing can be woven into Saint Brigid’s attire, the border of the image, or even subtly integrated into the background, including the structure of the Irish round tower. This will not only enhance the visual appeal but also pay homage to the rich heritage associated with Saint Brigid.

As with Harry Clarke, AI has not been trained on Irish round towers. Another issue with this image is that the fox’s head has been weirdly disconnected from his body. The interlacing looks more like basketweaving than anything else, but the richness of some of the details is impressive. I spent a lot of time asking DALL-E to refine this image to get a better round tower but I gave up after numerous failures and asked this instead.

ME: Please design an new image of St Brigid as an elderly nun with the following elements – a lamp, oak leaves, Celtic knotwork, and a romanesque-style church in the background

DALL·E: For this new image, I will design Saint Brigid as an elderly nun incorporating the elements you’ve requested: a lamp, oak leaves, Celtic knotwork, and a Romanesque-style church in the background. The image will capture the essence of an aged Saint Brigid, reflecting wisdom and serenity. The lamp will symbolize guidance, the oak leaves strength, and the Celtic knotwork will add a touch of cultural depth. The background will feature a Romanesque-style church, known for its semi-circular arches and sturdy appearance, providing a historical and architectural context to the scene.

ME: I like the left one – can you put in some colour and insert a small fox

DALL·E: I can create a new version of the image you prefer, incorporating color and adding a small fox to the composition. The addition of color will bring vitality and depth to the scene, and the fox, a symbol of cleverness and adaptability, will enhance the storytelling aspect of the image. Let’s see how this updated, colorful version with the fox turns out.

Jeepers – she’s aging before my eyes! I took a rest after that, but came back to it again later. The image at the top of my post came from this second session and is one of two (the second is below) that resulted from this request:

Please illustrate St Brigid in a flowing green cloak which spreads out behind her to create fields, with a medieval village in the distance.

I decided to try to illustrate some scenes from her life – stories taken from my previous blog posts about Brigid (you can read them by clicking this link). The first is a story from her childhood, concerning butter.

ME: St Brigid as a young girl churning butter, with other maids milking cows.

DALL·E: Here are two illustrations of St. Brigid as a young girl churning butter, set in a pastoral Irish setting. Around her, other maids are engaged in milking cows, all within the beautiful, green Irish countryside. This scene captures the simplicity and beauty of rural Irish life and St. Brigid’s early connection to service and the land.

Me: Thank you! Now, I would like an illustration of St Patrick anointing St Brigid as a nun, by putting the veil on her head. [I know it wasn’t St Patrick, but St Mel, but I wanted to keep it simple.]

DALL·E: Here are two illustrations depicting the moment St. Patrick anoints St. Brigid as a nun by placing a veil on her head, set inside an ancient stone chapel. This sacred and timeless scene captures the solemnity and grace of the ceremony, with St. Brigid kneeling in humility and determination.

But of course St Brigid was a bishop herself so I thought I would like to see what DALL·E made of that.

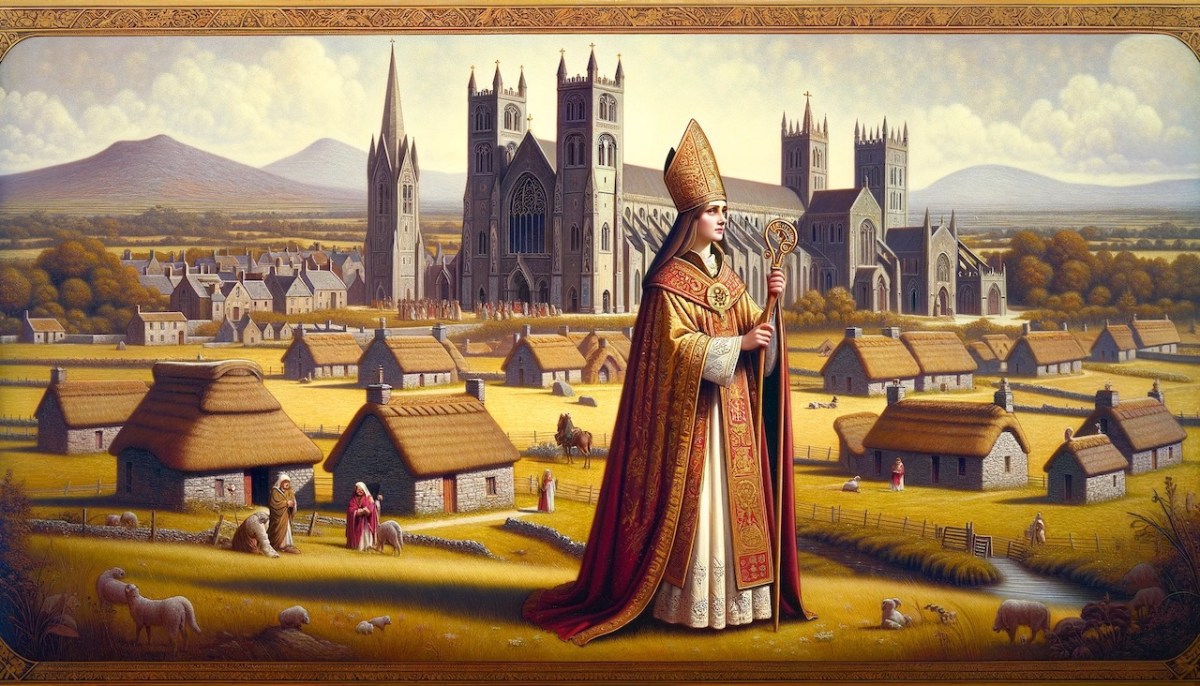

ME: St Brigid was recognised as a bishop and ruled over the ecclesiastical city of Kildare in the 6th century. Can you illustrate that?

DALL·E: Here are two illustrations depicting St. Brigid recognized as a bishop and ruling over the ecclesiastical city of Kildare in the 6th century. The scenes capture her majestic presence in bishop’s robes, holding a crozier, with the ancient city of Kildare and its community bustling with activity in the background. These images reflect the historical significance of St. Brigid’s role and the thriving spiritual community she led.

I tried several times to get DALL·E to remove the cathedral, but it was unable to do so, producing in all 8 different versions, all slightly different but all with an enormous church in the background – asserting each time that there was no church in the image. Here’s one version, in which the church gets even more enormous.

And here’s perhaps the strangest one – a cross between the Infant of Prague and a twee ye olde English village scene – and still with the enormous gothic cathedral!

I will finish with a final image, one of two generated when I said:

Me: I’m working on a piece about St Brigid of Ireland – her national holiday this year is Feb 5. Can you produce an image for me that celebrates that?

DALL·E: Here are two illustrations celebrating St. Brigid of Ireland for her national holiday on February 5th, set in an idyllic Irish landscape. Each image captures the essence of peace, heritage, and Irish culture, featuring St. Brigid in her iconic green robe, holding a lantern and staff, with a Celtic cross around her neck, amidst a beautiful backdrop of the Irish countryside.

I’ll leave it at that. I’d be really keen to hear what you, dear readers, think of DALL·E and its potential as a blogging tool.

Posts about St Brigid