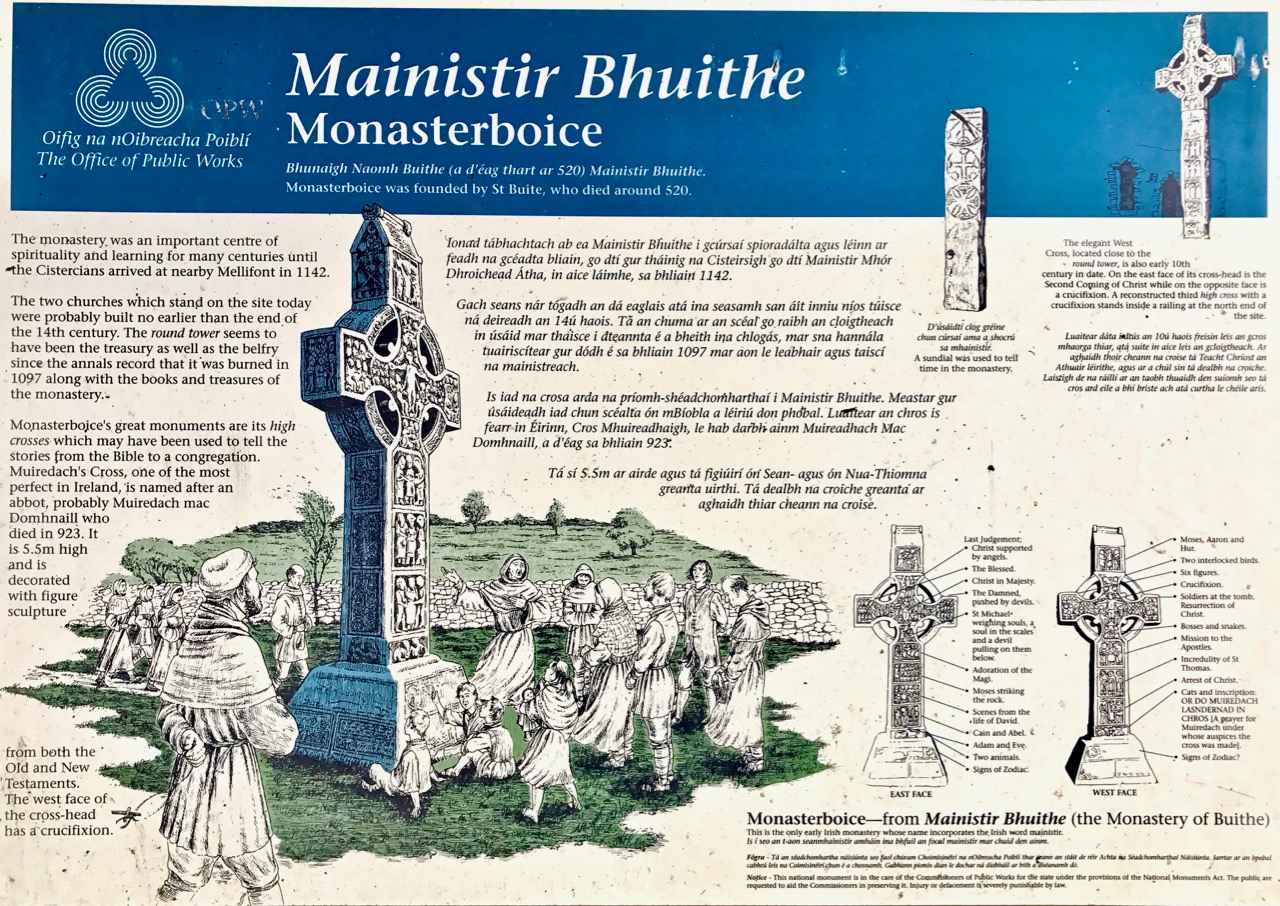

It’s been a long time since I wrote about a castle – you might like to refresh your memory about castles in West Cork, with a quick read of some of the posts on this page. They contain all kinds of details about castle architecture and lay-out, as well as the history of many of our West Cork castles.

The castle I am writing about today, Ballinacarriga, is one of the best preserved and has many unusual details. It’s located just south of the Bandon River, between Dunmanway and Enniskean. The black and white illustration at the top of the post is from The Dublin Penny Journal of 1834. The sepia photo is from James Healy’s notebook, upon which he based his book Castles of Cork. (Reproduced by kind permission of Cork County Council Library and Arts Service.) Unfortunately, the castle is normally only really viewable from the outside, as it is quite hazardous to navigate internally. I have been very lucky indeed to have been able to visit it, including the interior, a couple of times, most recently in the company of eminent archaeologist and medievalist, Con Manning. Con was able to point out to me several features that I would not have understood on my own.

This is a ‘ground entry’ castle – they were built later than the ‘raised entry’ castles of the O’Mahonys and are consequently more designed for comfort (fireplaces!) and more likely to be inland rather than coastal. This one was a castle of the Hurley (Ó Muirthile) clan, although it may also have been built (or acquired, or relinquished) by the McCarthys. The Hurleys managed to hang on to it until the mid-1600s when it was seized by forfeiture and handed over to the Crofts. The castle shows up in Jobson’s Map of Munster, completed around 1584, noted as Benecarick Castle – can you see it? It’s right where it should be, but don’t forget that this map has south on the left and north on the right.

One authority says that the tower was probably built in the late 1400s and the upper floors modified in the later 1500s but that is not obvious from an examination of the architecture. Let’s look at the outside first for some of the unusual features of this castle – beginning with the Sheela-na-gig (for more on Sheelas see our post Recording the Sheelas).

The Sheela can be seen in the image of the front of the castle above, between the second and third windows (from the bottom) on the right hand side. Here’s a 3D rendering by the marvellous Digital Heritage Age 3D Sheela project. It’s great to have this, as the Sheela on the castle is high up and hard to see in any detail. Its placement does seem to suggest that it was there to ward off the evil eye, one of the many theories about the function of Sheela-na-gigs.

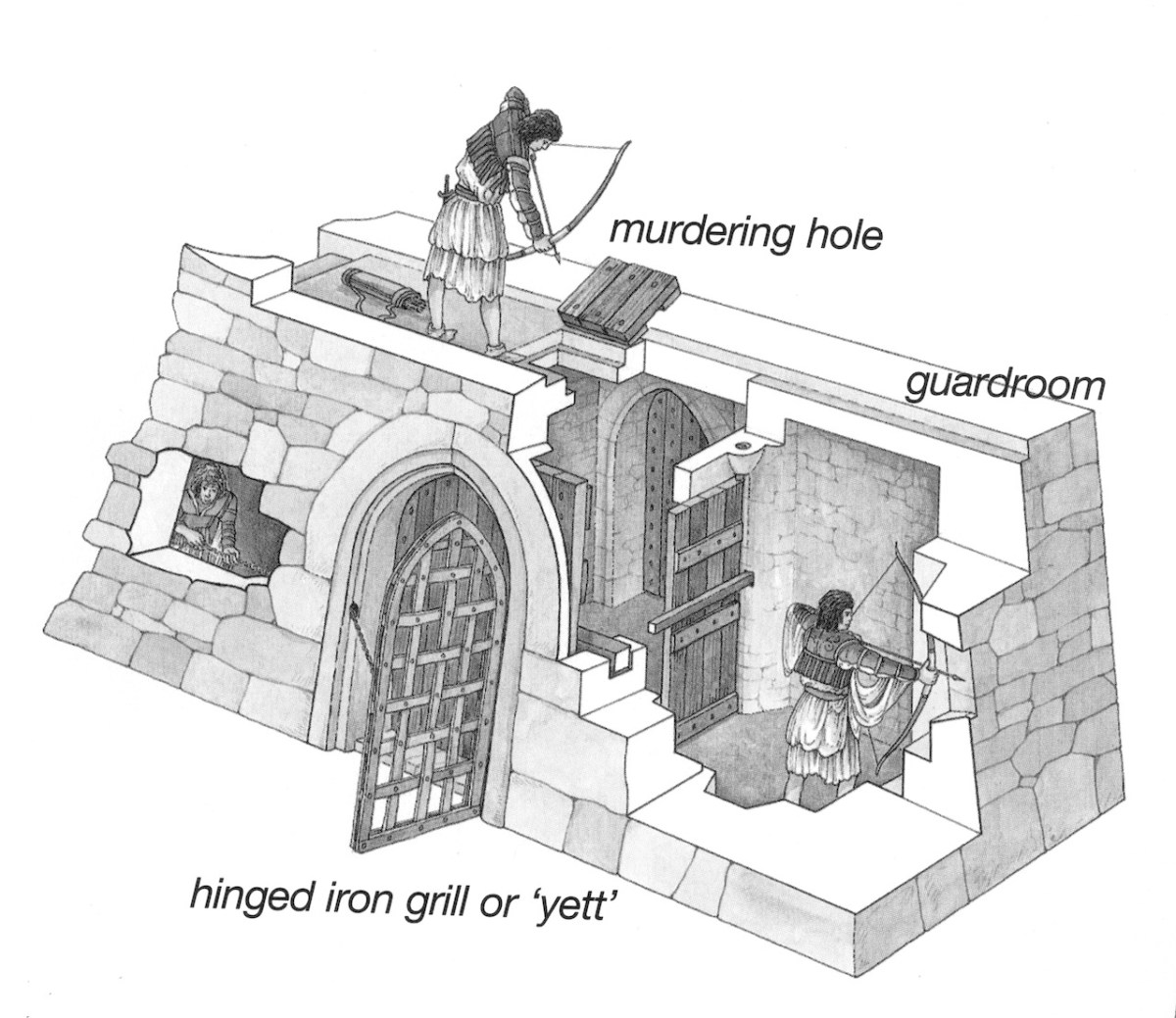

The door, as mentioned above, is at ground level – this necessitated different kinds of defences than a raised entry which could only be accessed via a stairway that could be detached and thrown away from the castle. Ballinacarriga had an iron gate that could be pulled across the door from inside, via a hole in the stone surround.

This feature was known as a yett. The chain that pulled it closed was managed by a sentry in a small sentry room to the left of the doorway. There is no sign of a murder hole above the entry lobby, as there is, for example, at Kilcrea.

Outside, we can see other defensive feature – bartizans, which are small projecting turrets at the corners, and a space that probably held a machicolation (like a bartizan but on a straight stretch of wall) over the door.

We also see the base batter and a garderobe chute (above) – chute exits are normally near the ground but this one emptied its content at first floor level, leading no doubt to a foul-smelling area that had to be regularly cleaned by an unfortunate individual.

Inside the main space is vaulted and there are at least two floors under it and a possible third or mezzanine floor. The second floor must have been a residential space as it contains an impressive fireplace.

In a window surround at this same level (the arched one to the right of the fireplace) we can see the first of several carvings. It’s a figure of a woman with five rosettes, interpreted as Catherine O Cullane and her children. It’s an extraordinary detailed carving and I couldn’t help searching the internet to see if I could find analogous illustrations – and I did!

Obviously Catherine enjoyed the height of contemporary fashion. The black and white illustration shows her French hood and apron, while the Holbein portrait is a good representation of her puffy sleeves and open collar.

There are more carvings and more features to come – part 2 next week!