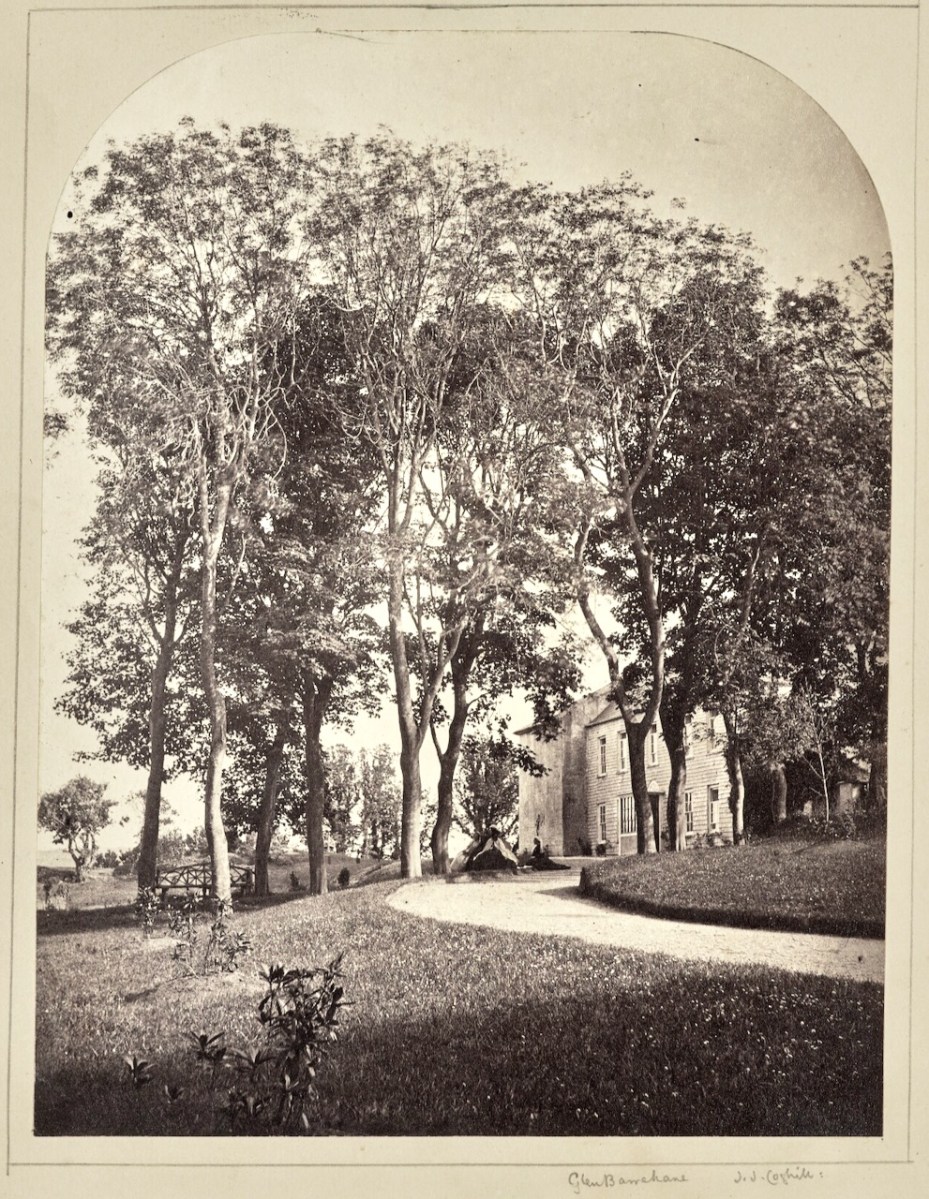

Castlehaven. – an important record of what the castle looked like before it fell down

In last week’s post, which I called a Trailer, I introduced this Early Irish Photographer. Congrats to Elizabeth and Sean who knew the identity of the mystery man. The photographer was Sir John Joscelyn Coghill, 4th Baronet, uncle to Edith Somerville (Adelaide, Coghill’s sister, was her mother) and father of Neville and Egerton Coghill. Neville was to die a hero’s death at the Battle of Isandlwana during the Zulu wars, and Egerton was to marry his first cousin, Edith’s sister Hildegard.

JJC (as he often styled himself) moved to Castletownsend in 1860, bringing with him a large family and several good-looking sisters, including Adelaide. Edith described him as my Uncle, Sir Joscelyn Coghill, leader of the second wave of invasion, with a photographic camera (the first ever seen in West Carbery) and a tripod. He used all his friends and relations as subjects, including himself (above).

Glen Barahane, originally called Laputa, in honour of Dean Swift who had once visited Castletownshend

By this time he was already an established photographer, although this was only one of his many avocations. He came from a wealthy family and had grown up in Belvedere House, Drumcondra in Dublin. According to his entry in the Dictionary of Irish Biography (DIB):

Coghill . . . took a special interest in photography in the early 1850s, when wet-plate photography and a number of photographic paper processes became available to amateur photographers. He was present at the inaugural meeting of the Dublin Photographic Society (1854–8) on 1 November 1854 and was elected honorary secretary. He served a term as president and three terms as vice-president. In May 1858 the DPS changed its name to the Photographic Society of Ireland and amalgamated with the fine arts section of the RDS.

JJC travelled widely on the continent, writing about his photography trips and offering advice to others (e.g. Seek official permission to photograph public buildings, and, if crowds gather when a camera is taken out, do not show irritation, but encourage them to be your ally rather than your enemy.) He was a staunch defender of photography as art – a hard sell with many traditionalists. From the DIB:

In May 1858 Henry McManus, RHA, headmaster of the school of art in the RDS, delivered a lecture on art in which he pointed out that the artist’s craft could not be superseded by mechanical means. The artist’s hand required the guidance of intelligence, McManus said, and this action could not be imitated by the use of machinery, however ingeniously contrived. Coghill differed with McManus on this occasion, and later in the year (November), when he replied more fully in a lecture at the RDS, Coghill described how photographers should study and reflect on art principles and not be mere servile copyists. He believed that photographers should use their intellect, taste, and judgement on the subject matter in front of the camera lens and so raise their photographic work from the mechanical to the sphere of art.

JJC was an immediate favourite in Castletownshend, along with his brother, Kendal, with whom he was close. They brought with them an interest in spiritualism and infected everyone with it.

Her Coghill uncles Joscelyn and Kendall thrilled her by their psychic feats. On 3 April 1878 she records: “Mother heard from Uncle Jos (Sir Joscelyn Coghill Bart, the head of the family) who was at a grand seance and was levitated, chair and all, until he could touch the ceiling.’ Professor Neville Coghill his grandson has informed me of the tradition that the Baronet signed his name on the ceiling in pencil.

Somerville and Ross, A Biography by Maurice Collis, Faber and Faber 1968

JJC’s daughter, Ethel, Edith’s first cousin and Castletownshend ‘twin’ wrote this about her father:

He was a real peter pan – a boy who never grew up in many ways, full of enthusiasms of all kinds, whether it were yachting, music, painting, writing, acting, photography, spiritualism, speculation – all had their turn and he flung himself into each and all with a fervour that lasted at fever heat for a time. At one time after my mother’s death [1881] he and his brother Kendal took a house in London for some months. To it they brought a considerable amount of the family plate and a presentation set of gold belonging to my uncle, as well as my grandfather’s medals and other valuable things. They left the house for some weeks in charge of two maids, who promptly brought in their young men, cleared the house of nearly all the valuables and had the cheek to order a sumptuous luncheon in my father’s name and a landau in which they went to [the races]. My father was in Ireland when the telegram came to inform him of what had happened. I did not see him for some time afterwards. By then, he had come to look on the thing as a huge joke. Nothing was ever recovered, but he felt as though he had been part of a Sherlock Holmes mystery, and this compensated him for everything he had lost.

Edith Somerville, A Biography by Gifford Lewis. Four Courts Press .2005

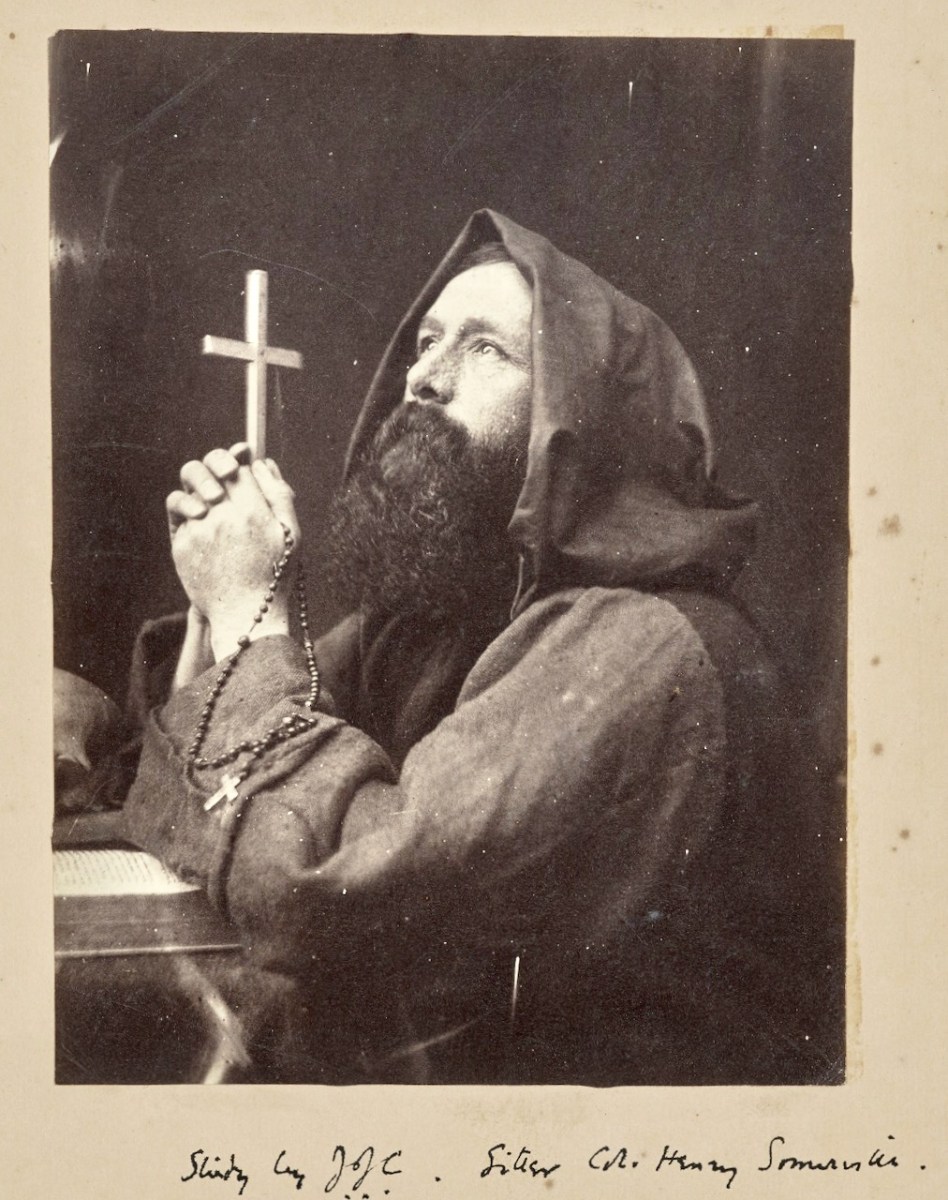

The Coghills lived in Glenn Barrahane (no longer there) and the house was the centre of many activities – amateur theatricals, singing, séances, painting expeditions. The Somervilles, his nieces and nephews, adored him and his brother Kendal. He must have had a good relationship also with their father, his brother-in-law, Henry Thomas Somerville, as he often cast him in ‘character studies.’ – Henry, in turn, must have been good-humoured and patient.

But tragedy struck too – Neville was only 26 when he died at Isandlwana in 1879. He was awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously, in 1907. When he died his younger brother, Egerton, became the heir. Originally wealthy, the family’s fortunes suffered several setbacks and most of their fortune was wiped out by bad investments. As Maurice Collis puts it, On 29 November, 1905, at the age of 79, sir Joscelyn Coghill died, and life changed dramatically for Hildegard and Egerton, who inherited the baronetcy and a load of troubles.

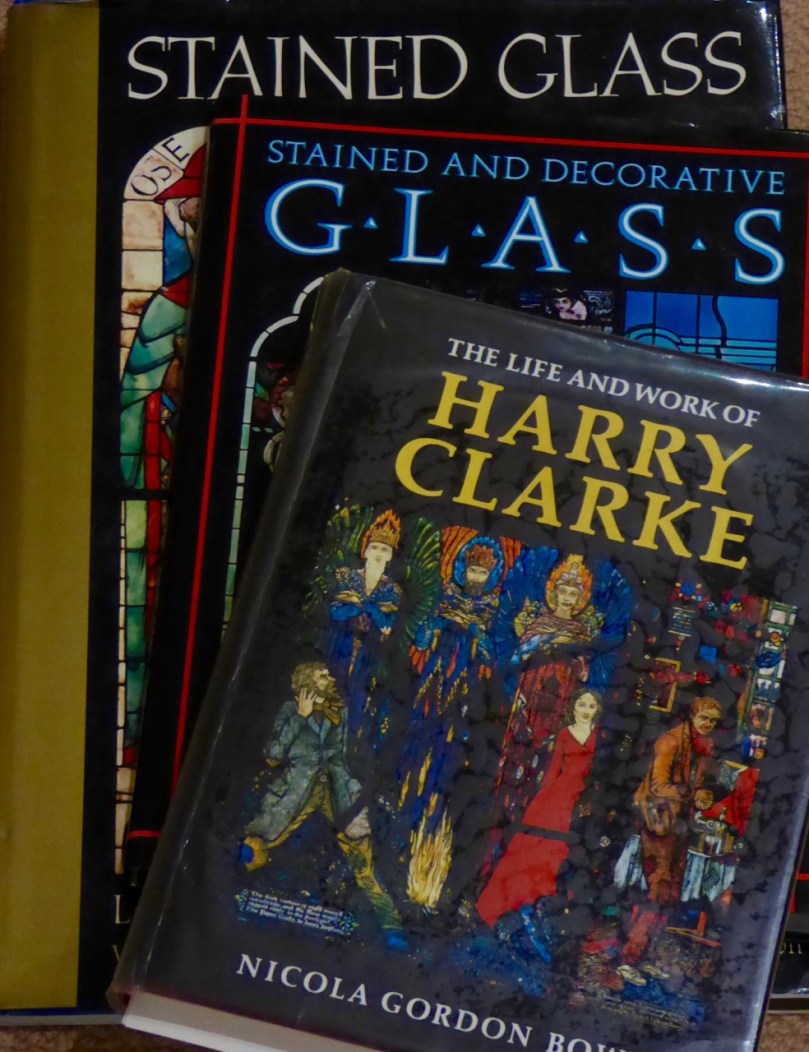

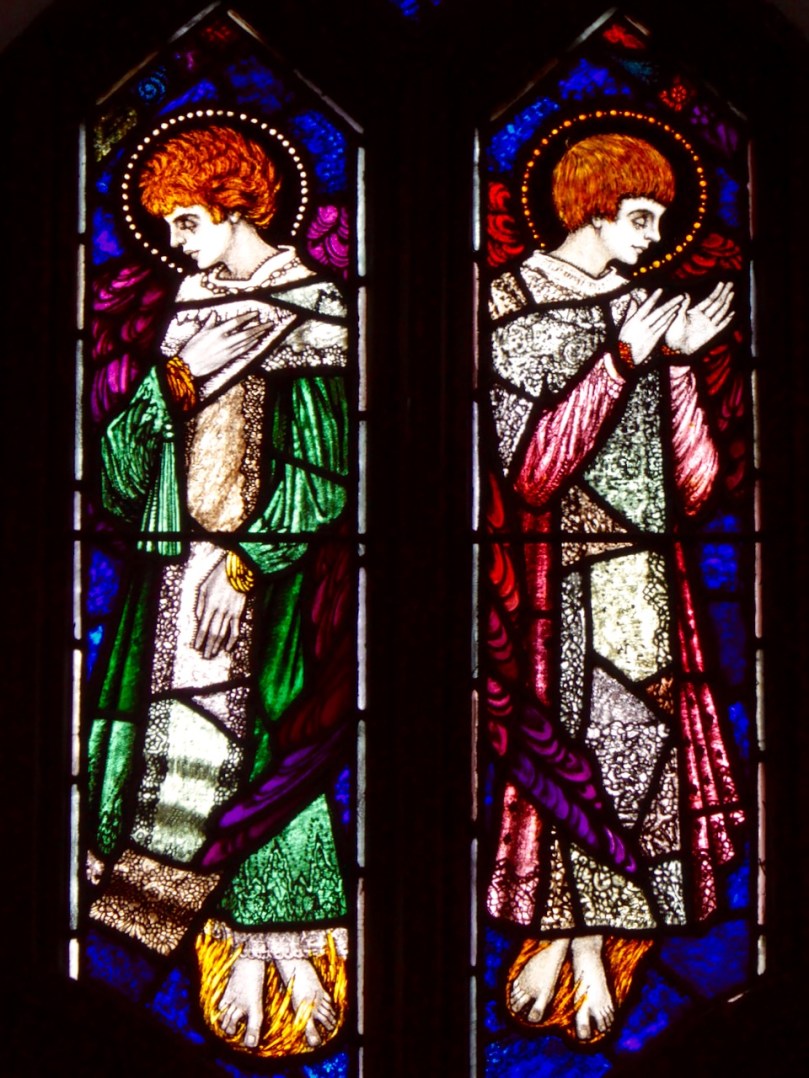

Egerton and Hildegard were so hard up they had to wait seven years before they could marry. Egerton died suddenly in London in 1921, and Ireland (and especially West Cork) was in such upheaval that it was many months before his body could be taken home. Read more about Egerton in my Post Harry Clarke, Egerton Coghill and the St Luke Window in Castletownshend. And more about jolly Uncle Kendal in The Gift of Harry Clarke.

Although far removed from Dublin, JCC chaired “the photographic committee of the Dublin International Exhibition (1865) [and] was credited with the success of the photographic section” (DIB). He continued to exhibit up to the mid-1870s, winning prizes for his photographs. I have included in this post photographs taken by JJC in and around West Cork. They constitute an invaluable record of people and places, taken between 1860 and his death in 1905.

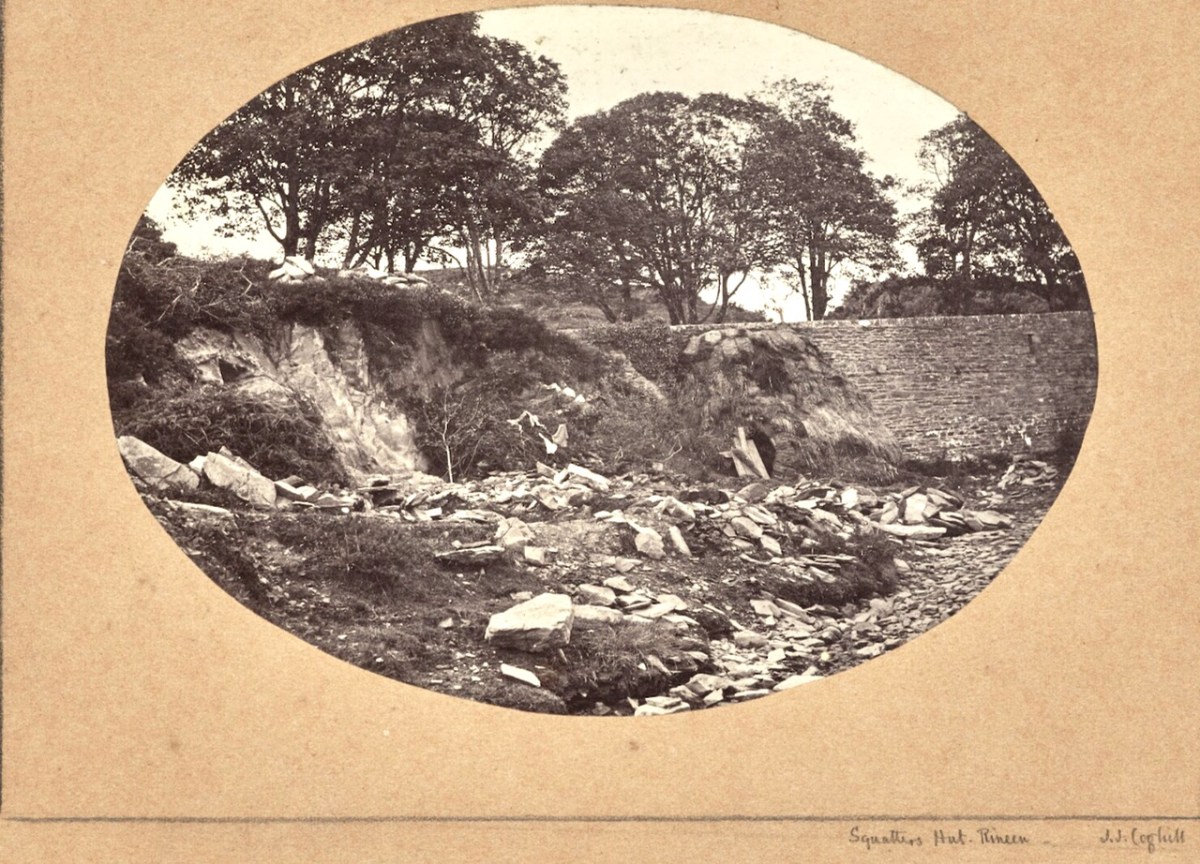

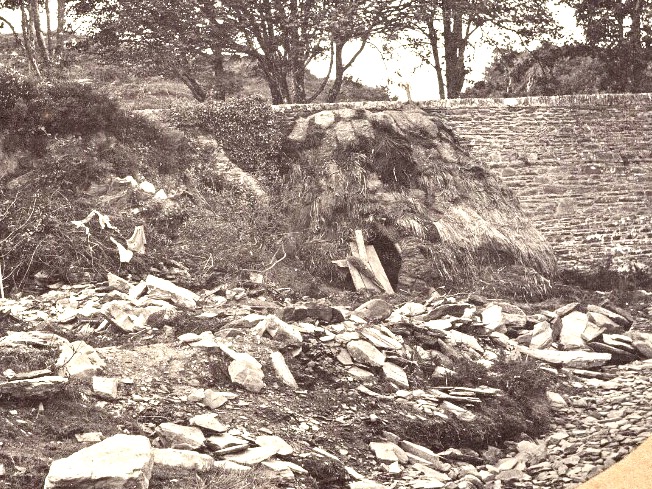

For example, the photo above, detail below, is of a “Squatter’s Hut, in Rineen (the same bridge I featured last week). It’s a fascinating and important image, as it is the only photograph I have ever seen of one of the miserable cabins (known as fourth-class housing), made of sod, in which many of the poorest people lived in West Cork before the Famine.

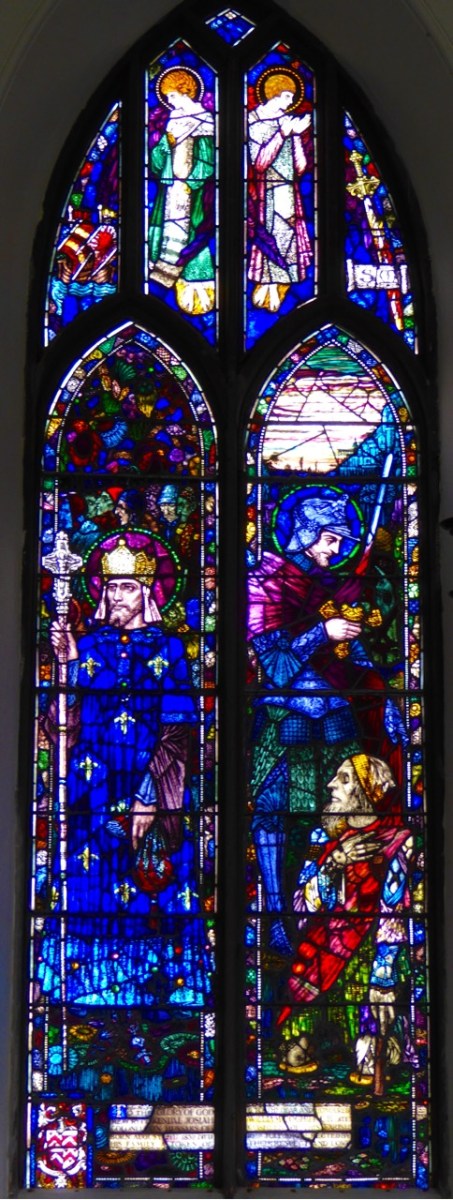

I am not sure how these photographs arrived into the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, but many of the images are now freely available on their website, copyright-free, and we are grateful for that. You can browse the whole collection for yourself. You can also visit St Barrahane’s Church in Castletownshend and see the fine windows for yourself, including this one by Powells of London, dedicated to JJC and his son, Neville. Can you spot the Victoria Cross?

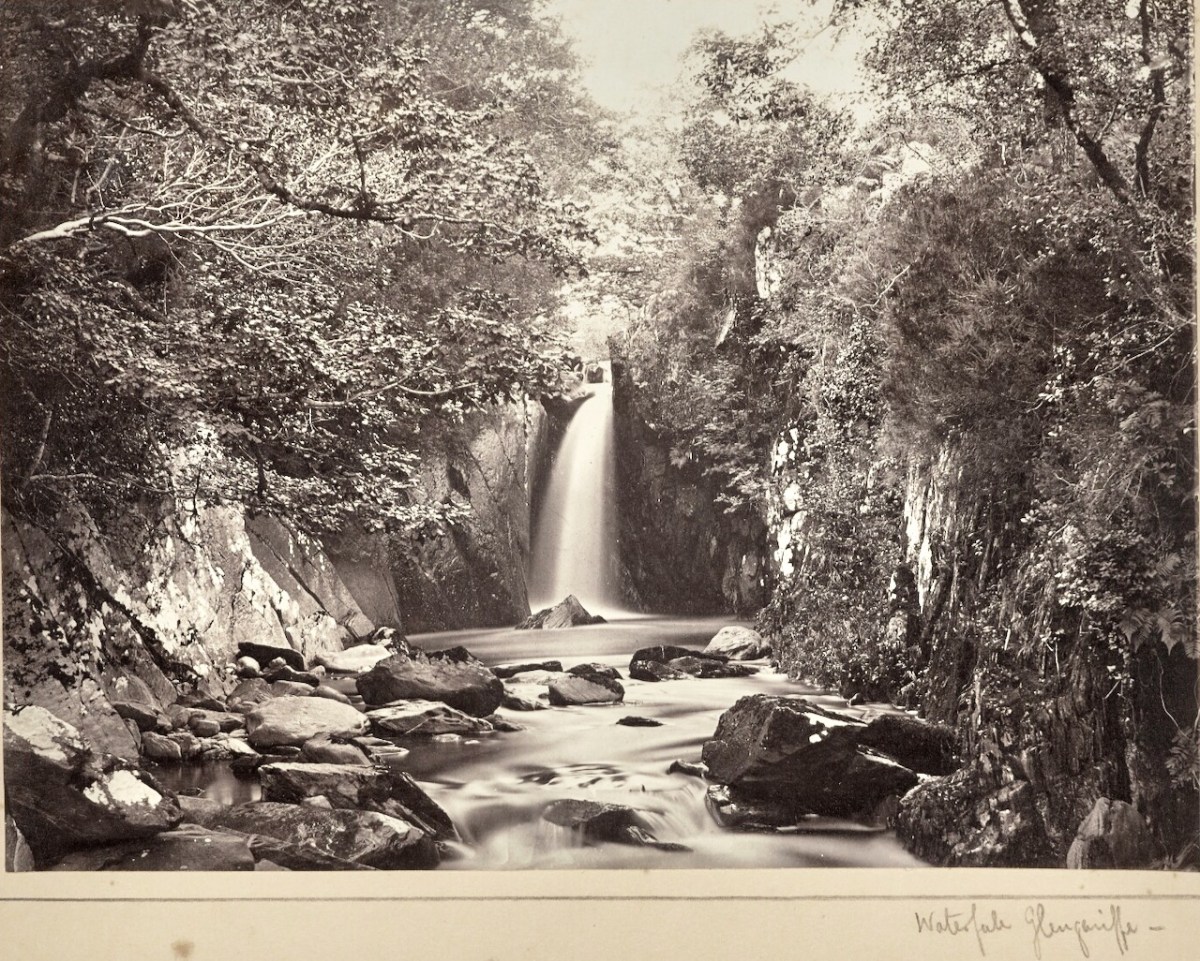

There are other memorials to JJC in that church too – take a look next time you’re there. I will leave you for now with one of JJC’s landscape photos, of a Glengarriff waterfall – a masterful shot for what was, at that time, quite a difficult subject to capture, moving water.