I had been aware of George Victor Du Noyer’s antiquarian drawings from my days as a student, but that did not prepare me for the Du Noyer exhibition currently running at the Crawford – it’s nothing short of breathtaking. Du Noyer, it turns out, was far far more than an antiquarian: he was a nineteenth century Renaissance man, artistic, talented, curious, scientific and learned in equal proportions. Stones, Slabs and Seascapes is curated by Peter Murray (recently retired director of the Crawford) and co-curated by Petra Coffey of the Geological Survey. If you do nothing else this winter, get to Cork to see this exhibition!

I’ve decided to annotate the images with quotes in italics (image follows quote) from the outstanding exhibition catalogue which is a collection of essays, each written from a slightly different perspective. I’ve tried to show representative samples of Du Noyer’s work, mostly from the exhibition. A couple of illustrations are from elsewhere. I’m not going to say a lot about Du Noyer’s life – there’s an excellent summary (with some additional photographs) by Fiona Ahern on the Maynooth University Library website.

From a cultural studies and critical theory perspective, the principal interest in Du Noyer lies also in seeing how, as an Irish artist, he responded to the international debates of his day: to the Devonian controversy, to the widening gap between ‘uniformitarianists’ and ‘catastrophists’, and to the urgent search by geologists and astronomers during his lifetime to explain the origins of the planet Earth. The ability of Du Noyer to traverse conventions of representation – he moved easily from picturesque watercolours, to scientific cross-sections of landscape – reflects a similar flux in nineteenth-century learning, where advances in science co-existed with a desire to adhere to traditional modes of representation. (From the Introduction by Peter Murray and Petra Coffey)

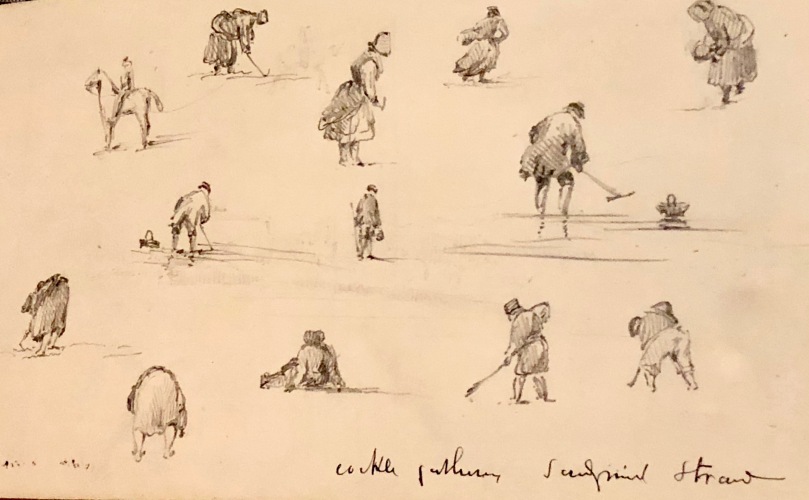

In contrast with other artists’ depiction of Ireland at this time (many of them English), Du Noyer’s sketches lack the stereotyping that is all too common in art of that period. Based on eyewitness observation, his drawings lack elements of caricature and satire often perceptible in depictions of Ireland by artists who tended to work from preconceived ideas. (From the Introduction by Peter Murray and Petra Coffey)

Throughout a long and productive lifetime, during which he depicted a myriad of objects and places in Ireland, George Victor Du Noyer compiled a databank of images that not only formed part of the new awareness of Irish national identity that emerged in the early nineteenth century, but also revealed the potential of art to frame revolutionary narratives relating to geology, natural history and human evolution . . . Du Noyer was one of those who helped construct this new narrative. He documented towns and villages, prehistoric sites and ruined monasteries. He had a keen interest in the natural environment, in methods of transport . . . artefacts connected with food preparation, cooking, eating and drinking. (From the Foreword by Peter Murray)

As industrial production began to dominate people’s everyday view of the world, the aesthetics of handmade objects fell into sharp relief. Du Noyer delighted in depicting such objects, from every age, from simple ‘Killick’ anchors of wood and stone, to querns for grinding corn and wooden drinking vessels. Removed from their original context and preserved in glass cases in museums, these objects had begun to lose much of their original meaning. In illustrating them, Du Noyer not only committed their image to paper but also highlighted philosophical questions relating to the passing of time and the formation of both individual and collective memory. (From the Foreword by Peter Murray)

When he was visiting Belfast in 1837, he bought some apples in the market thinking they were Irish apples (they were not) and he painted them magnificently, enhanced with gum Arabic. (From George Victor Du Noyer – Artist and Geologist (1817-69) by Petra Coffey)

From 1842 to 1843 . . . he accepted private work, as he was able to produce art work in many media . . . He illustrated Hall’s Ireland: Its Scenery, Character, etc (Vol.2, 1842). (From George Victor Du Noyer – Artist and Geologist (1817-69) by Petra Coffey)

The Geological Survey of Ireland (GSI) was established on 1st April, 1845 . . . Du Noyer had been introduced to the new study of the earth – geology – and it was to shape his life thereafter. Despite having no formal training or qualifications in geology he was to become extremely competent in his calling with the added bonus of being better able than most to record graphically what he saw . . . From now on, Du Noyer never put down his geological hammer, pencil, paper and watercolours . . . (From George Victor Du Noyer – Artist and Geologist (1817-69) by Petra Coffey)

Du Noyer published papers in many journals, including the Archaeological Journal. His most important work was ‘On the remains of ancient stone-built fortresses and habitations to the west of Dingle, Couny Kerry’, published in 1858. (From George Victor Du Noyer – Artist and Geologist (1817-69) by Petra Coffey)

The purpose of a scientific illustration is to reflect accurately the key features of a fossil, animal, plant or landscape. It can be a far cry from the conventional artist’s view, where the essence can be more important than the reality. (From The Scientific Illustrations of George Victor Du Noyer by Nigel T Monaghan)

Du Noyer’s scientific landscapes emphasise the geology, showing rocks accurately in terms of bed thickness, irregularity, angles of dip, faults and major joints, with no less attention to detail in his rendition of the soil cover, vegetation and the human impact on the countryside. (From The Scientific Illustrations of George Victor Du Noyer by Nigel T Monaghan)

. . . when Du Noyer worked with the [Ordnance] Survey, he would go out in all weathers to sketch antiquities surviving in the landscape, some of which are now in a more parlous condition than when he drew them, while others have disappeared entirely… (From Du Noyer’s Treasures in the Royal Irish Academy by Peter Harbison)

In 1837 Du Noyer painted a series of large watercolours depicting typologies of Bronze Age spears and axeheads, and early Christian artefacts, such as brooches, bells, devotional crosses, and figures clearly prised off reliquaries. (From George Victor Du Noyer – Where and When by Peter Murray)

in 1837 and 1838, Du Noyer drew a series of palaeontological monochrome-wash watercolours, depicting fossils of ancient life forms, including seashells, whorls, spirals and other simple shapes, images that were lithographed for Portlock’s Report on the Geology of Londonderry . . . Portlock’s publication, at over 500 pages, was, literally, ground-breaking in terms of the study of fossils in Britain and Ireland. (From George Victor Du Noyer – Where and When by Peter Murray)

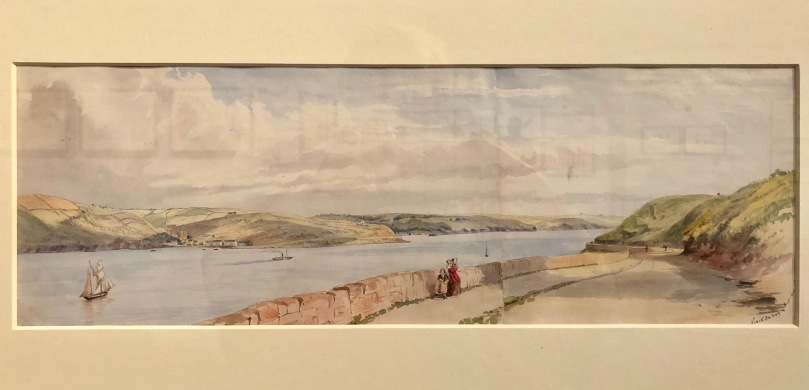

In May 1850, he painted four panoramic watercolours from the top of Carrickbyrne Hill . . . [and] also painted a panoramic watercolour, ‘View of Ballyhack and Arthurstown from Passage’. (From George Victor Du Noyer – Where and When by Peter Murray)

In 1867 . . . after many years working for the Geological Survey of Ireland as an assistant surveyor, Du Noyer was appointed District Surveyor and posted to a field station in County Antrim . . . His article, ‘Notes on the stratigraphical position of the Giant’s Causeway, and the structure of the Basaltic Cliffs immediately adjoining it,’ had been published in The Geologist in 1860. (From George Victor Du Noyer – Where and When by Peter Murray)

In total, Du Noyer left some five thousand works of art, in pencil and watercolour. At his best, he combined an objective scientific approach with a sublime artistic vision. (From George Victor Du Noyer – Where and When by Peter Murray)

The exhibition runs from November 17th, 2017 to February 24th, 2018 at the Crawford Art Gallery in Cork and then from March to September 2018 at the National Museum of Ireland, Dublin.

Catalogue published by Crawford Art Gallery, available from their book shop.

Lovely work. Thanks

LikeLike

Thank you, Maura.

LikeLike

This looks a stupendous exhibition, his work is breath-taking – must ge up there soon

LikeLiked by 1 person

really interesting. Thank you for posting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Must get to see this exhibition, looks wonderful.

LikeLike

You would definitely enjoy it, Peter.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on West Cork History.

LikeLike

Finola, his water colours remind me of Hercules Brabazon’s paintings

LikeLike

Now that you mention it…

LikeLike