From 1883 to 1892 in Britain, a periodical called St Stephen’s Review was one of the many journals that catered to a conservative (and Conservative) view of the Empire – a Unionist, Loyalist position that saw anything that threatened the social and political order as anathema to the best interests of Britain. Magazines like this employed cartoonists to illustrate their pages and encouraged them to be as savage as they liked. One of the masters of the genre was William Mecham who took the professional name of Tom Merry, and in each issue he provided a political cartoon commenting on the times. Each one was as superbly drawn as it was vicious and as pointed as it was unsubtle.

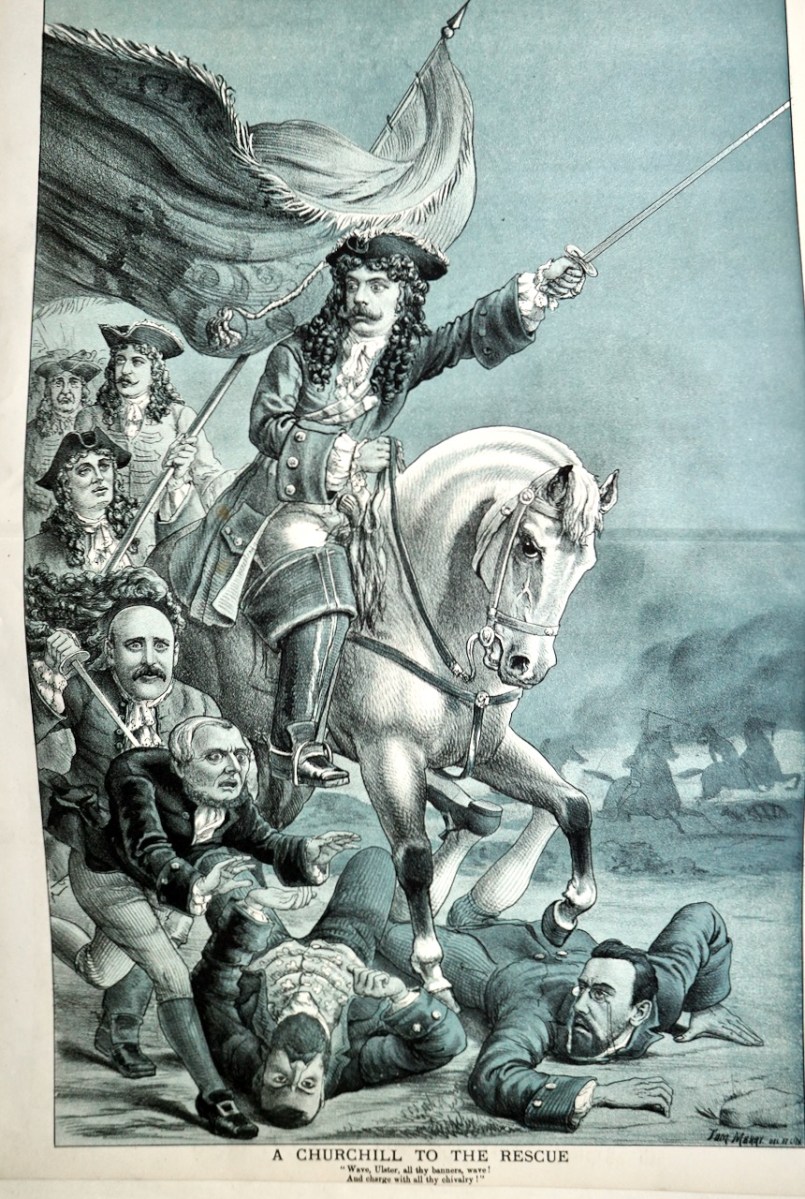

In this one, designed to appeal to Unionists, Lord Randolph Churchill is depicted as King William of Orange trampling the Home Rulers. Merry’s portraiture was outstanding (that’s Churchill below) and his readership would have instantly understood who his subjects were.

In order to place these cartoons in their historical context, a little Irish history is called for, so what follows is a brief and necessarily over-simplistic outline of what Tom Merry was responding to in his cartoons.

During this period the British Parliament was obsessed with The Irish Question. According to historian Conor Mulvagh, “The rise of Charles Stewart Parnell within the Irish Parliamentary Party of the late 1870s ran parallel to a rapidly evolving agrarian crisis.”* In fact, three overlapping and often conflicting strains of Irish activism run through the 1880s. The first is that of national self-government through constitutional means – Home Rule – the goal of the Irish Parliamentary Party led by Parnell.

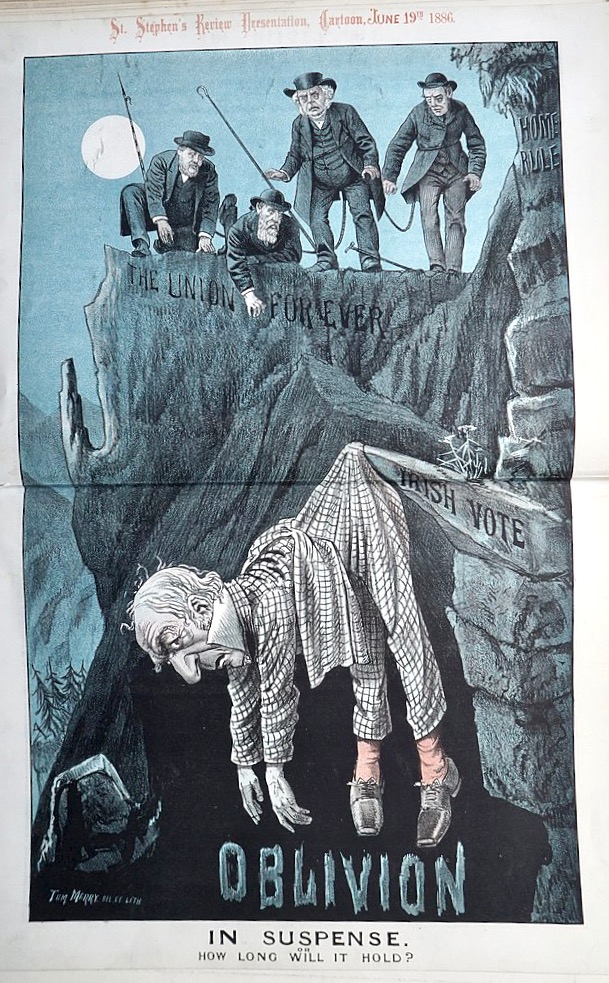

Gladstone, depicted by Merry always as the main threat to stability and Empire, hangs by a thread because of his dependence on the Irish vote

The second strain is that of land reform and this was a period of significant agrarian action led by Michael Davitt and the Land League. After spending much of his youth involved in the IRB, Davitt had become an advocate of non-violent agitation and civil disobedience and used these techniques to great effect in the Land League (see Robert’s post on Michael Davitt). Despite the emphasis on peaceful protest, clashes and skirmishes did occur, including the Mitchellstown Massacre in 1887.

In case the message wasn’t clear enough, Merry would add labels. Erin is sporting Plan of Campaign (more about that next time) and Murder, while a potion bottle on her table has the word Dynamite on it. The discarded clothes are Law and Order, Rights of Property and British Rule

William Ewart Gladstone by Millais, courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

The third strain was represented by the Fenians – Irish revolutionaries who had staged an unsuccessful uprising in 1867 and many of whom were living in exile in the United States. In the 1880s, orchestrated by O’Donovan Rossa from his base in New York, the Fenians carried out their Dynamite Campaign in England, causing injuries, deaths, and real terror (see my post, O’Donovan Rossa – The First Terrorist?, for more about the Fenians’ operations on Britain). While the Fenian Dynamite Campaign was condemned by the Irish Parliamentary Party and by Davitt’s Land League, both of whom saw it as undermining their objectives, it had an enormous impact in Britain, hardening sympathies against the Irish.

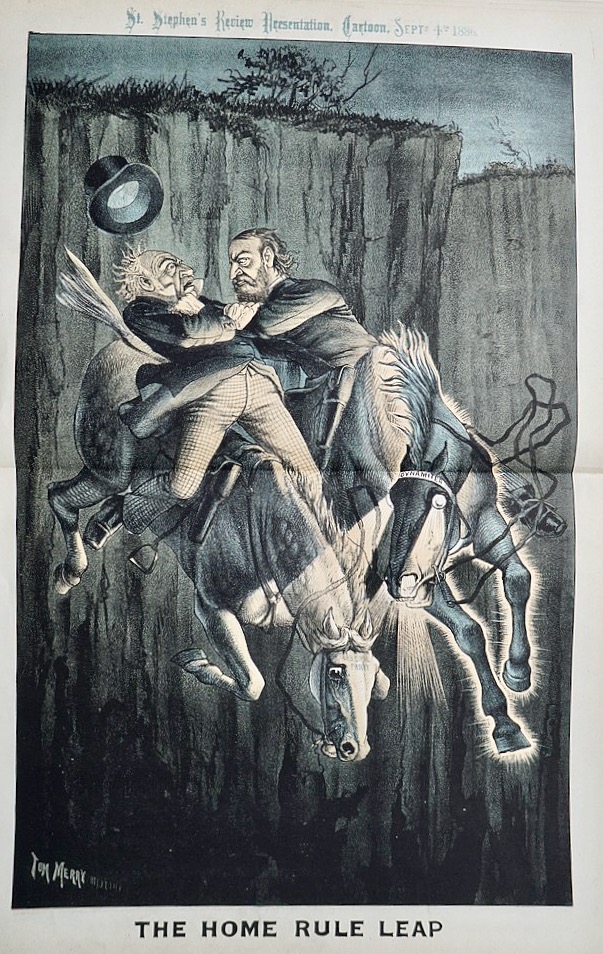

Gladstone and Parnell leap into the void together

The causes of constitutional and agrarian reform, however, found much common ground and the Parliamentary Party and the Land League, Parnell and Davitt, eventually entered an alliance known as the New Departure. “For Parnell, the New Departure offered the alluring prospect of hitching the the rather abstract concept of Home Rule and national Self-Government to the more emotive, popular and established political cause of the land.”*

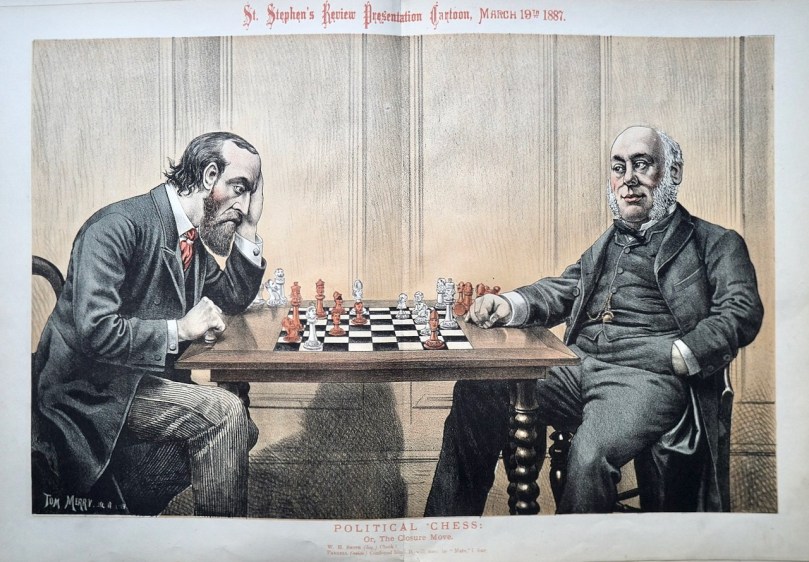

Parnell, looking stressed, plays chess against a confident William Henry Smith. Smith (that’s him below) was the original book seller who founded the modern chain that bears his name. A member of the Conservative party, at one point he was appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland. Each of the chess pieces is labelled. Can you recognise Victoria?

The British Parliament was in essence a two-party system by the 1880s – Liberals represented fiscally progressive and socially liberal ideals, while Conservatives represented pride in Empire and loyalty to monarchy and tradition. Elected parliamentarians from Ireland from the Unionist tradition aligned with the Conservatives, whereas Parnell’s nationalists supported Gladstone’s Liberals on a quid pro quo basis.

W H Smith courtesy if the National Portrait Gallery

Given the Conservative politics of the St Stephen’s Review, Tom Merry’s cartoons cast Parnell and Gladstone as villains. The cartoons often feature shadowy Irishmen in the background, masked and carrying dynamite. Although his Irish caricatures were not as outrageously simian in their features as those of the infamous Punch cartoons, they are often shown as drunken and thuggish.

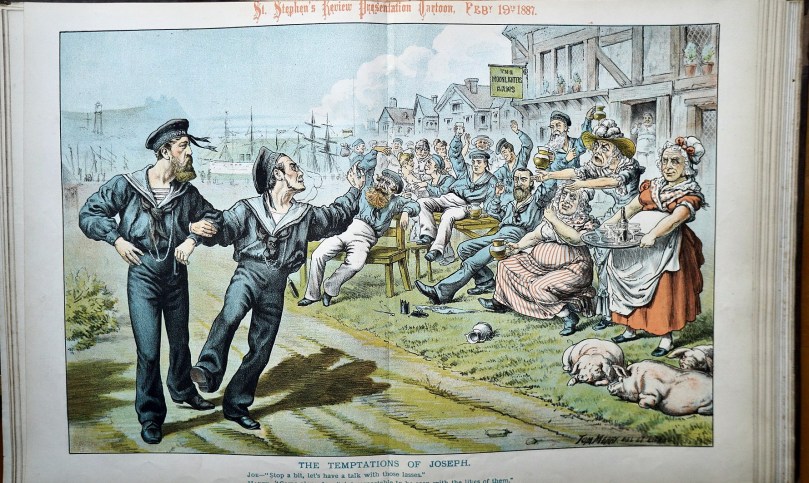

Two sailors wearing HMS Union hats are bing tempted to join the other side

This post will serve as a brief introduction to Tom Merry’s cartoons on The Irish Question. In a subsequent post I will include examples with more Irish politicians who played a leading role in the great events of the times. I will leave you with one of my favourite Merry Cartoons below – every nation, it seems, loves Victoria and being part of her Empire, except the ‘scapegrace’ Irish man, skulking away with his dynamite, his gun, and his shillelagh.

Do you know of any libraries which have bound copies of St Stephen’s Review ?

LikeLike

No, I don’t. Have you come across them?

LikeLike

I enjoyed reading your blog post! I have always loved the genre of political caricature. Unpolished history, unsubtle as you say, sometimes one-sided, but always amusing.

LikeLike

And so talented too – it’s like magic to me that somebody can capture a likeness so well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! Such talent. These little gems are the slices of real life. Glad they have been preserved.

LikeLike

I just finished rereading William Manchester’s The Last Lion, a biography of Winston Churchill’s early life. It went into extensive detail about Randolf Churchill’s career…so I was better prepared for your blog. Thanks for feeding our brains as we stay home to stay safe!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Shelley. It’s been fun figuring out who all the characters in his cartoons are. Most are no longer household names so I’m only catching a fraction.

LikeLike

Brilliant post, Finola. Merry’s cartoons are incredibly accomplished drawings. I really enjoyed this post.

LikeLike

Thanks, Dermot. He was a new discovery for me. He certainly captures his subjects!

LikeLike

It’s complicated! But you have explained it clearly and the cartoons get right to the point, the final one is particularly interesting – it all went askew finally, for Britain, but a long struggle ahead for Ireland.

LikeLike

I think there may be Brits who still see history as Tom Merry did. More to come – it’s a bit of a challenge to set the context succinctly.

LikeLike