The Iveragh is the largest of the Atlantic peninsulas of Ireland: it is, perhaps, also the most romantically named. In Irish it is Uíbh Ráthach – ‘descendants of Ráthach‘. But we don’t know who Ráthach might have been: a Gaelic chieftain, a notable family – ancient inhabitants lost even to legend? Certainly this terrain is amongst the wildest and most beautiful in this green island. Today we are focussing on just one Kerry townland which encompasses a deep vein of history stretching back to prehistoric times.

The townland of Caherlehillan is defined by mountains. To the north is Knocknadobar (header and above), to the east Mullaghnarakill, and to the south Caunoge. The Fertha River flows down from Coomacarrea and creates a long, fertile valley floor which opens to Valencia Harbour at Cahersiveen.

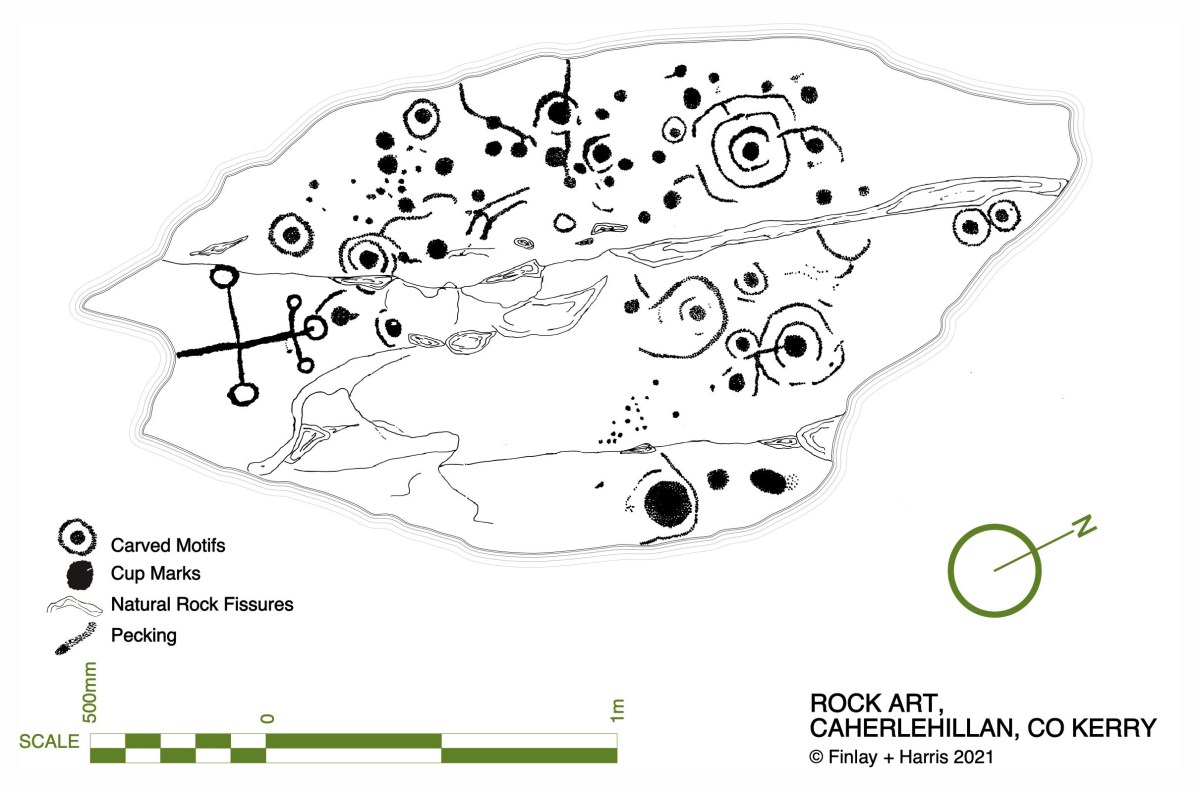

It would be reasonable to assume that the river valley would have supported communities in ancient times, and the recorded archaeology of the area confirms this. The earliest antiquities include a Bronze Age stone row and – possibly Neolithic – Rock Art, explored and recorded by Finola fifty years ago: an eager student travelling alone through the wildernesses on a borrowed Honda 50!

Upper picture – stone row in Caherlehillan townland; lower – Finola’s drawing of Rock Art made in 1973 for her UCC thesis. Note the cruciform motif at the southern end of this large sandstone boulder: it is probable that this carving dates from a later period, and may have indicated its use as a Mass Rock in penal times. However, the ‘Patriarchal Cross’ format is unusual in this context, and warrants further study. Since Finola travelled those boreens, many more examples of Rock Art have been revealed in the area and are now identified on the Sites and Monuments records. On our visit to Caherlehillan we searched the hillsides in vain for some of these more recently discovered panels (below).

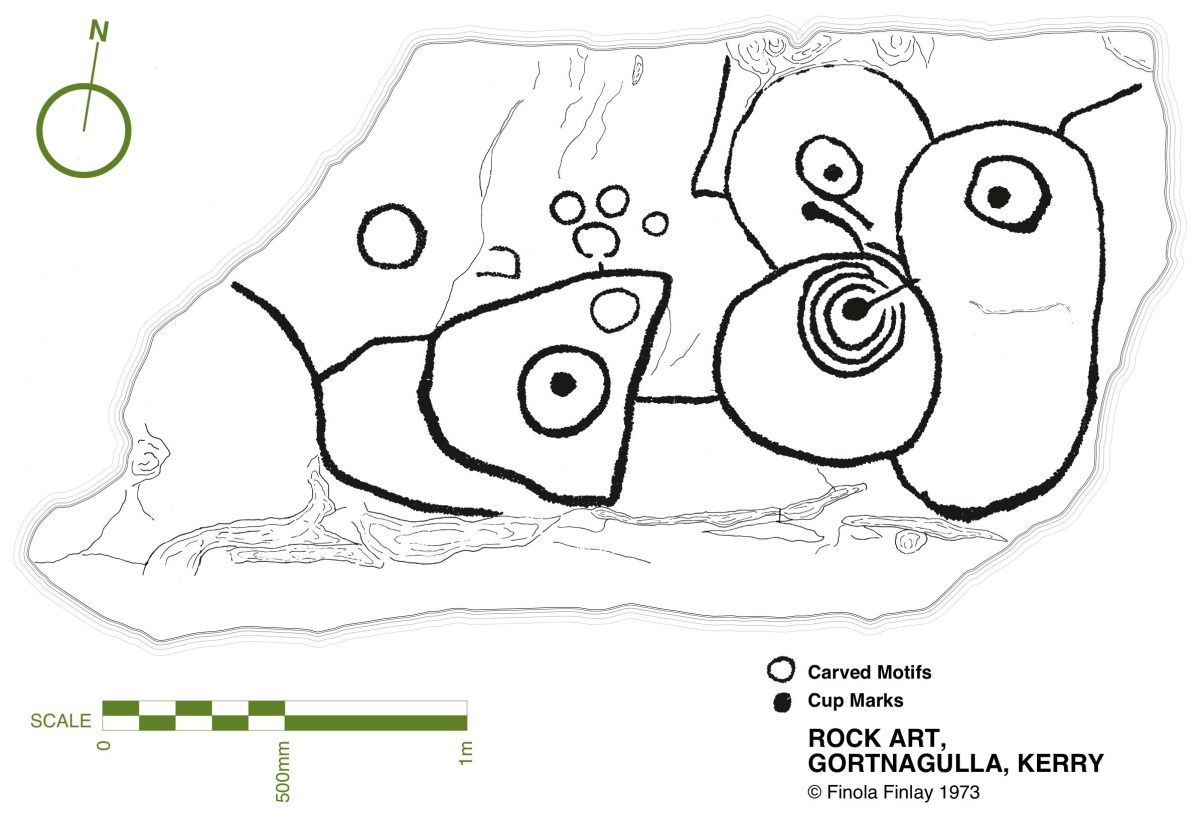

This further representation of Rock Art (above), also recorded by Finola, lies on the borders of the townlands of Caherlehillan and Gortnagulla: the motifs are quite unusual.

The central feature of Caherlehillan is the Caher (above), which gives the townland its name. The suffix ‘lehillan’ is probably from the Irish Leith-Uilleann, meaning half-angle, or elbow. There is a sharp bend in the Fertha River below the settlement, and it is most likely that this natural feature gave rise to the nomenclature. A Caher (Irish Cathair) is a stone fort, and is distinguished from a typical earthen rath, or ring-fort, by its size and construction. Forts, whether stone or earthen, were the dwelling places and shelters of people who lived in the first millennium in Ireland. Generally, stone-built forts were larger than earthen examples and are likely to have been inhabited by higher status families or communities. They would have been impressive structures and good views over the surrounding landscape was a requisite. Interestingly, the word Cathair is also given the meaning ‘city’ – ‘monastic city and settlement’ – and ‘Paradise’ (Teannglann). All of these could be relevant, as close to this Caher is an early ecclesiastical settlement.

This picture shows the spectacular setting of the Caher; the previous views show the extent of the enclosing stonework. Today it is a desolate place: many of the walls have been partially dismantled for use elsewhere, and the only close habitation is a single farm dwelling just below the fort. In this remote yet beautiful site it is hard to imagine the activity that was focussed here a thousand years ago.

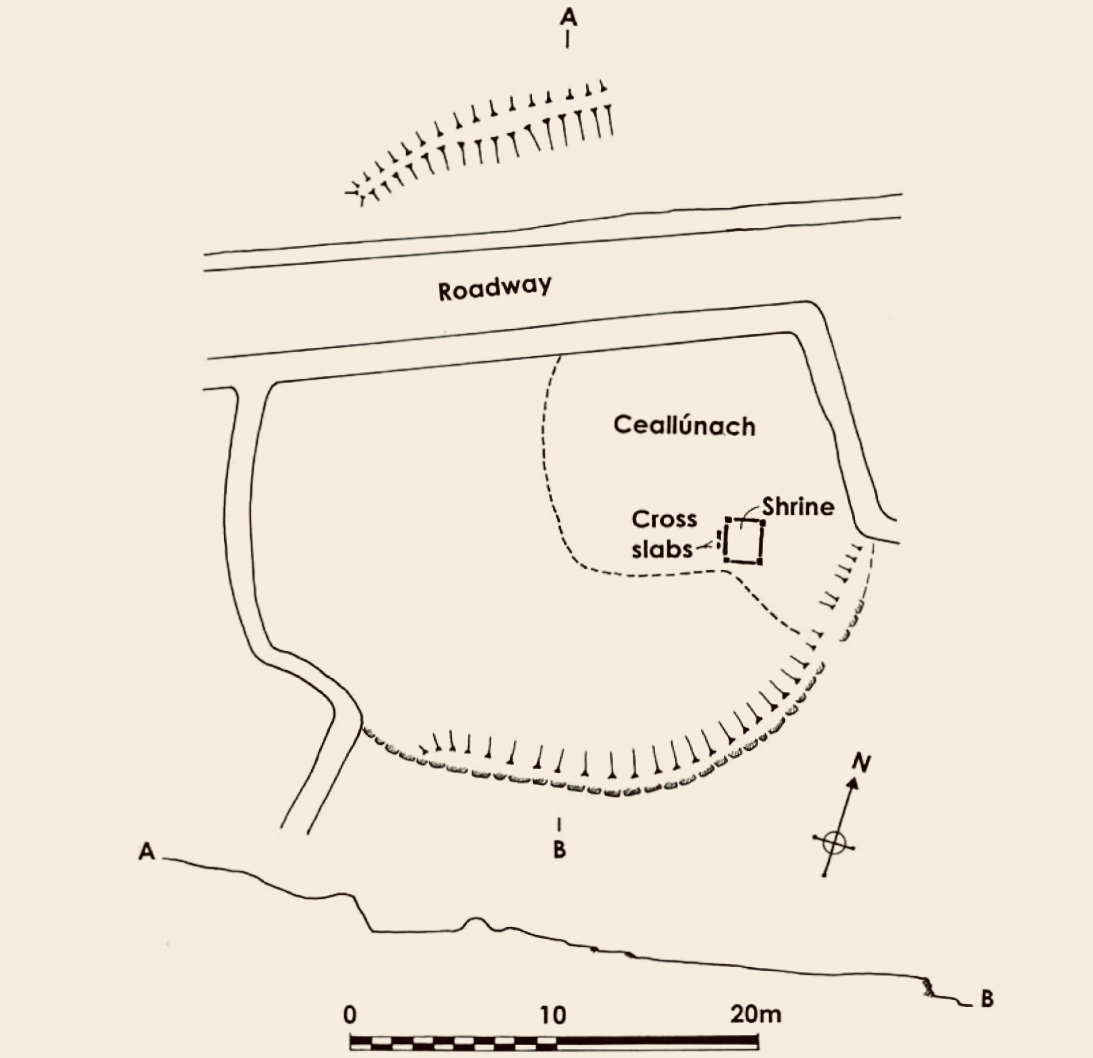

Just to the west of the lone farmhouse is a small enclosure, bounded by stone walls. It would be easy to overlook this, but for one feature which stands out (above). It catches the eye because it is so unusual: a square box structure with stone sides and corner posts, and two upright engraved cross-slabs facing down the valley. Quartz rocks form a raised bed within the square. Around this ‘box’ are a number of low, unshaped stones set in the ground. This was long thought to have been just a children’s burial ground – a Ciilín or Ceallúnach, but we now know that this was a later use. Between 1994 and 2004 the site was substantially investigated and excavated by students from University College Cork’s Department of Archaeology under the direction of John Sheehan, with remarkable results.

. . . Recent excavations at the early medieval ecclesiastical site at Caherlehillan, Co Kerry, have resulted in the discovery of important information on its initial development and structure. The ritual core of the site, consisting of a church, cemetery and shrine (which probably originated as a ‘special’ or founder’s grave), dates to what is probably the formative phase of Christianity in the south-west of Ireland. The picture emerges of a site that was conceived and built as a coherent entity in accordance with a clear conceptual template . . .

John Sheehan, A Peacock’s Tail: Excavations at Caherlehillan, Ivereagh, 2009

These two illustrations are from the Sheehan / UCC Excavation summary. The photograph is a good representation of the two upright cross-slabs, while the illustration shows two fragments which were found during excavation. Both show the same motif displayed on the smaller slab, yet each representation is to a different scale. This motif therefore occurs three times at this site.

This is the plan that was made at the commencement of excavation, showing the ecclesiastical site at Caherlehillan. The south-eastern boundary is a built-up stone retaining wall (shown on the photograph below), and the indicated embankment above the later roadway implies that this site was originally circular in form (courtesy John Sheehan). Carbon dating of excavated materials suggest a date of mid-5th to early 6th centuries for the earliest activity on the site, while activity appears to have ceased beyond the 8th century. Most importantly, the excavations revealed – to the north-east of the ‘shrine’ – the foundations of a timber church dating from the 5th century – possibly the earliest church remains ever found in Ireland.

The photograph above is from Church Island on Lough Currane, Co Kerry, a site which we visited recently. It shows the shrine of Saint Fionán Cam, who was the founder of that ecclesiastical settlement. The island foundation was set up in the sixth century, and the name of the holy man and his exploits are recorded for us to observe today. Sheehan suggests that the ‘box’ at the Caherlehillan site is also a founder’s shrine, but we have no record of who this ‘saint’ or holy man was. Four hundred years of occupation of the site have, apparently, left him without a name, either through inscription, implication or oral tradition.

The upper picture shows a detail of the carving on the smaller cross slab at Caherlehillan. Sheehan (and others) suggest that the bird representation is in fact a peacock, which features frequently in early Christian art. This is because the wonderful plumage of the bird is entirely renewed every year, through moulting, and this symbolizes the underlying Christian theme of death and resurrection. The relief carving (above) from Northern Italy is dated to the 8th century and shows two confronted peacocks, ” . . .symbols of paradise and immortality in early Christian and Byzantine art . . . “. Sheehan in fact goes further, suggesting that the symbols on the shrine stones at Caherlehillan show a direct link with early Christian influences from the Mediterranean, something that is borne out by ceramic fragments also recovered from his excavations. These are of of ‘Bii type’, a form of pottery of north-eastern Mediterranean origin that may be firmly dated to the period between the late 5th and mid-6th centuries.

So there we have it: a small, remote settlement in a wild Kerry mountainside that has given up its ancient secrets to us. Dwellers there left us enigmatic Rock Art, possibly 5,000 years ago. Their descendants populated the fertile valley, farming the land and building here a prestigious stone fort, while nearby – and contemporary with that fort – was established perhaps the very earliest Christian foundation in Ireland! Today the place is sparse and rugged but, in keeping with Ireland’s spirit, breathing with an almost remembered past.

The researches and writings of John Sheehan, lecturer in Archaeology at University College Cork have been invaluable in formulating this post.

Go hiontach mar is gnath.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Go raibh maith agat, a Bhreandán.

LikeLike

What a gorgeously rich landscape! That’s an interesting theory about the carved birds being peacocks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s the thinking, Jo, but I’m wondering whether they are doves…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aha! Well that could make sense too!

LikeLike

So much history hidden in the remote parts of this area. Thank you for exposing it to us.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are welcome, Oliver.

LikeLike

Such an early and important site, ironic that the name of the holy man in all this paradise has been forgotten. What a fantastic day we had 🙂 Some glorious photos too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Definitely a memorable day, Amanda!

LikeLike

That was certainly a memorable visit, enlightened by your research.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Peter. That was such a wonderful day!

LikeLike