A bit of a nostalgia trip for Finola and me this week: we spent a couple of days in Kerry and dropped in to Derrynablaha – the iconic valley which has some of Ireland’s most notable Rock Art. These stones were carved on natural rocks on the hillsides many thousands of years ago. To this day, we don’t know what they signify.

Some years ago, Finola and I organised exhibitions showing examples of Rock Art – many taken from Finola’s 1973 University of Cork thesis. The map above was drawn for the exhibitions: you can find Derrynablaha in the centre of the Iveragh Peninsula, left of centre. Below is a rendering of Finola’s thesis drawing showing – arguably – the most significant piece of Rock Art on this island:

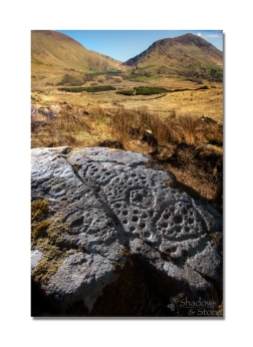

Here’s a photo of these rocks which I took on my first visit to this valley, in 2012. It was a dull day! The next photo was taken on a better day three years later. This shows how weather conditions can affect the way that Rock Art motifs are seen:

On our most recent visit – last week – we didn’t have time to scale the steep hillside to view this rock formation, but we enjoyed just taking in the stunning landscapes of the townland.

Above, and in the header picture, you can see the ruin of the cottage, which was once the only dwelling in this valley. It was still lived in when Finola visited to carry out her survey of the Rock Art in 1972 – fifty years ago. Then it was occupied by John O’Sullivan and his sister, May. John’s brother – Daniel – discovered much of the Rock Art in the surrounding landscape and reported this in the 1960s to Michael Joseph O’Kelly, then Professor of archaeology at UCC, and his wife Claire. Subsequently the O’Kellys made some expeditions to Derrynablaha, as did the Italian rock art expert, Emannuel Anati. Daniel had died prior to Finola’s visits and she recalls that the remaining family were excellent stewards of the Rock Art, ensuring that it was preserved and not damaged. She has ‘hazy memories’ of being brought into the house and given cups of tea and brown bread.

After we had published earlier posts about Derrynablaha, Finola was contacted by Faith Rose – the great niece of the O’Sullivans who lived in this cottage in 1969: Faith had visited the valley in that year. She recalls:

. . . I remember their bedroom was downstairs, the staircase to the upstairs being unsafe. There were none of the usual services in the house. There was an old fashioned fireplace where you could cook with a settle at the side. I seem to remember being told it had been built under some government scheme and the original stone farmhouse was to be seen slowly returning to nature close by. I wonder if you recall any of this. My great aunt and uncle were shy people who extended us the best hospitality. To my sister and I it was a magical place, but the hardness of their lives there was clear . . .

Faith Rose 2021

There are the ruins of several other buildings set within this landscape, indicating that the settlement was once significantly more populated in earlier times. Now it is wildly lonely, but impressively beautiful. When Finola carried out her surveys, she recorded 23 pieces of Rock Art. Today it is recognised that there are 26 known examples, with a further 7 stones in the adjacent townland of Derreeny. Long term readers of this Journal may recall that we visited the townland in April of 2015 – together with a small group of enthusiasts – to seek out all the known examples. At that time Ken Williams was using techniques he had developed to photograph the carvings in fine detail. These employed several portable light sources. The following sequence shows one of the rocks (number 12) taken without lighting; Finola’s drawing traced in 1972; then Ken’s technique in action and his results, which are remarkable:

Once again you are reading about the Rock Art at Derrynablaha! There have been several posts on this subject over the years, but we make no apologies: we never tire of the beautiful landscapes of Kerry – and we have seen it in all weathers. It would be good if we could be closer to solving the meanings of these rock carvings; this is unlikely to happen. Over the last 300 years since the phenomenon was first recorded in Ireland (and Britain, and many other places in Europe and the world) there have been varying theories – dozens – put forward for its existence: none of them is conclusive. Think on . . .