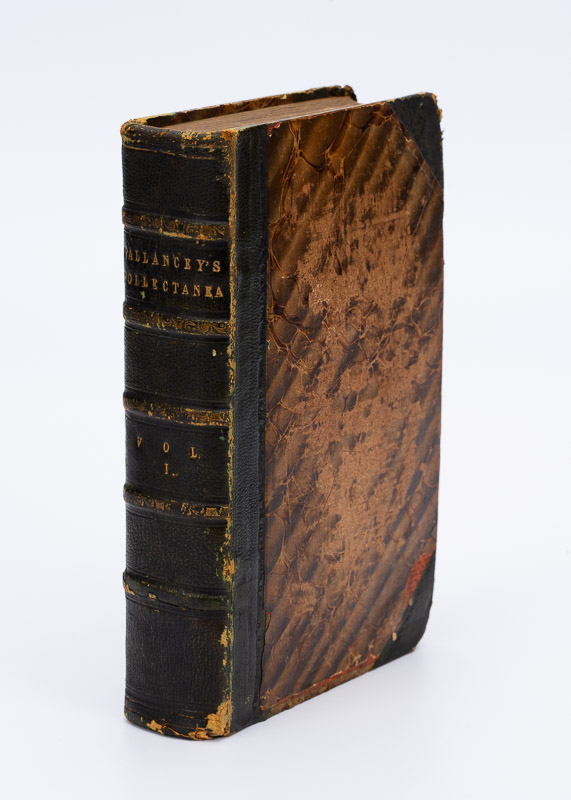

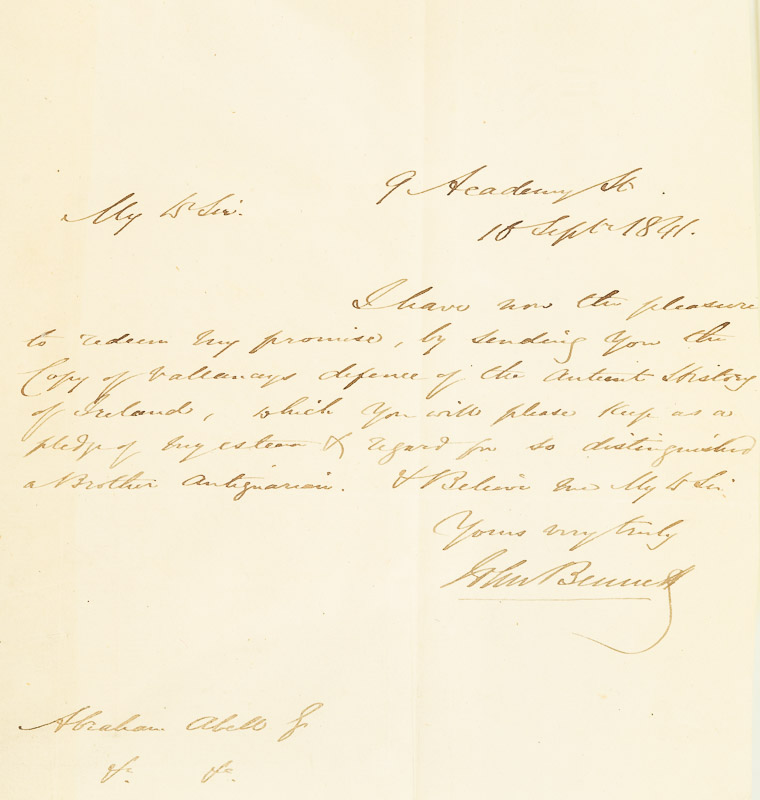

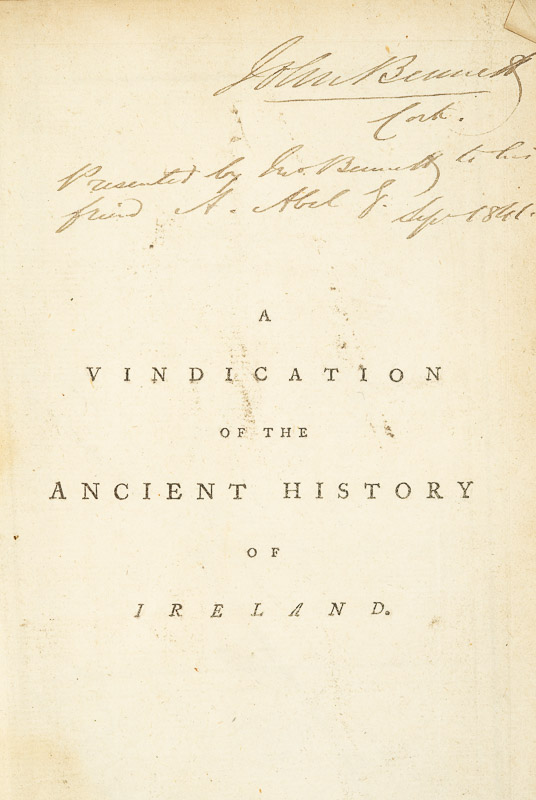

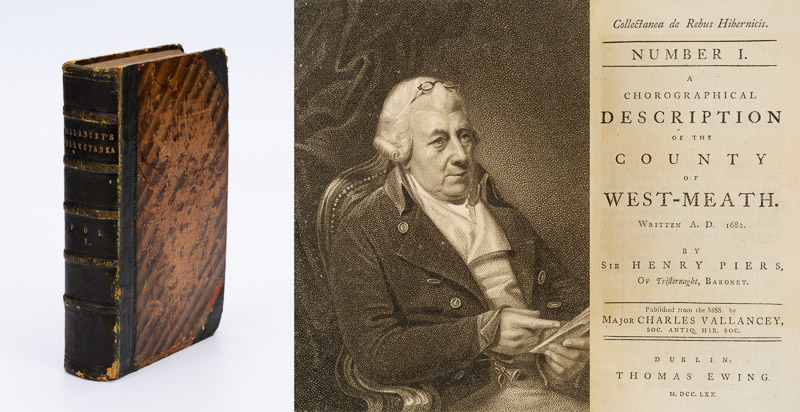

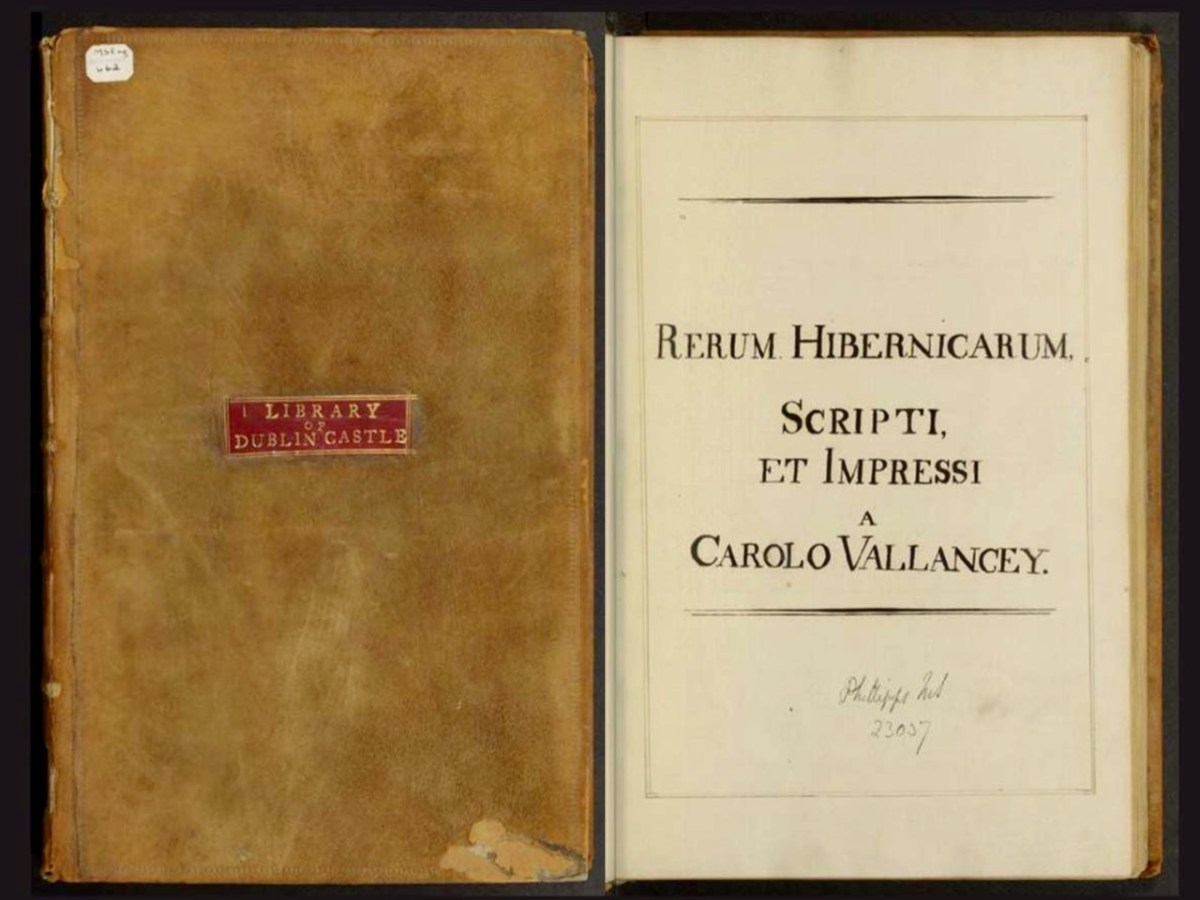

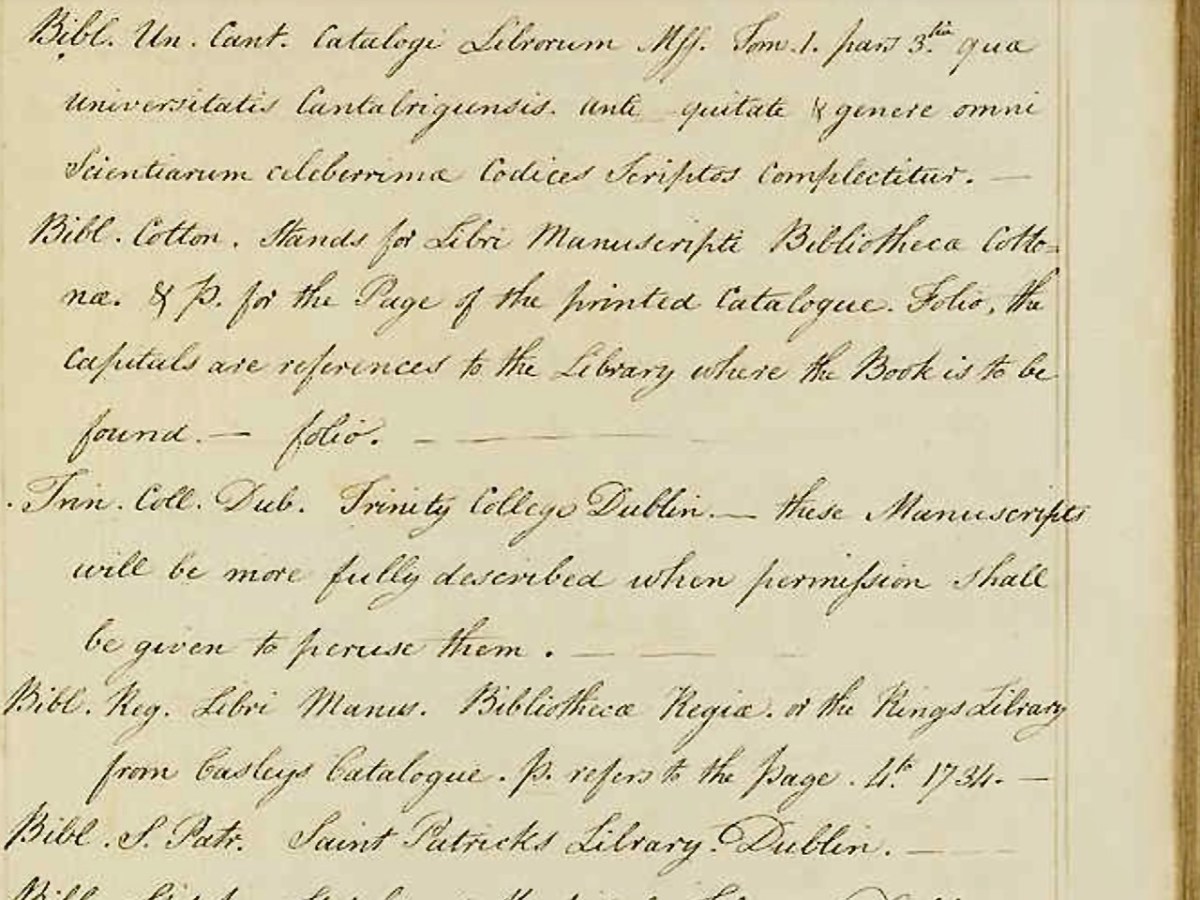

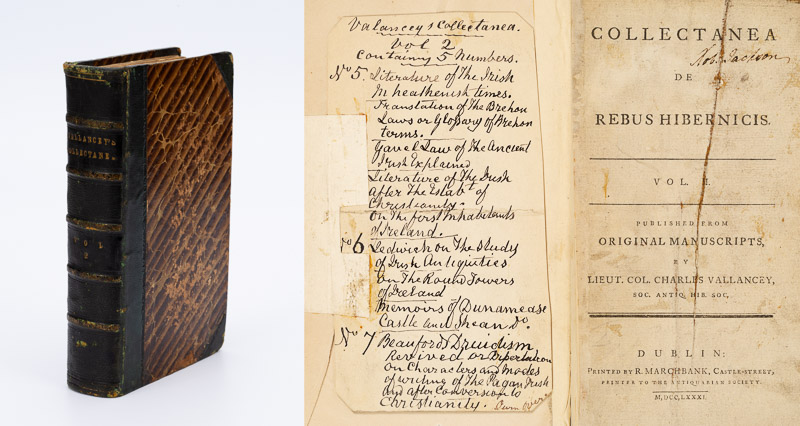

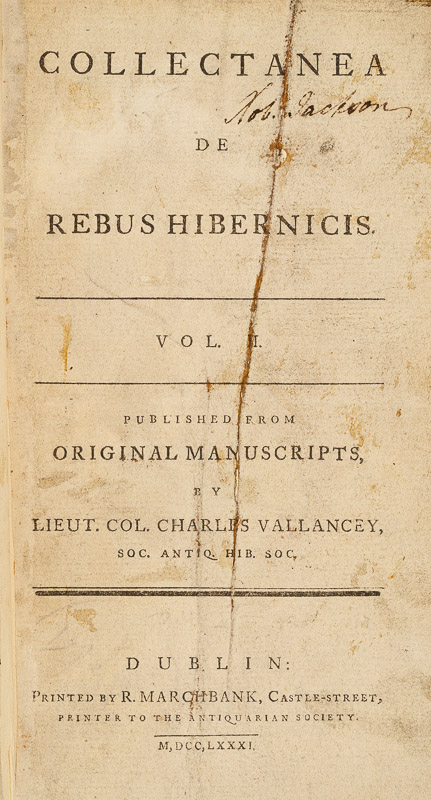

Remember I told you that Vallancey was not above publishing the work of others, and omitting the name of the author, thus giving the impression that he had written it? Was this deliberate or not? Were the standards of plagiarism the same then as they are now? He does give a kind of attribution in Vol II, below, but it’s not precise.

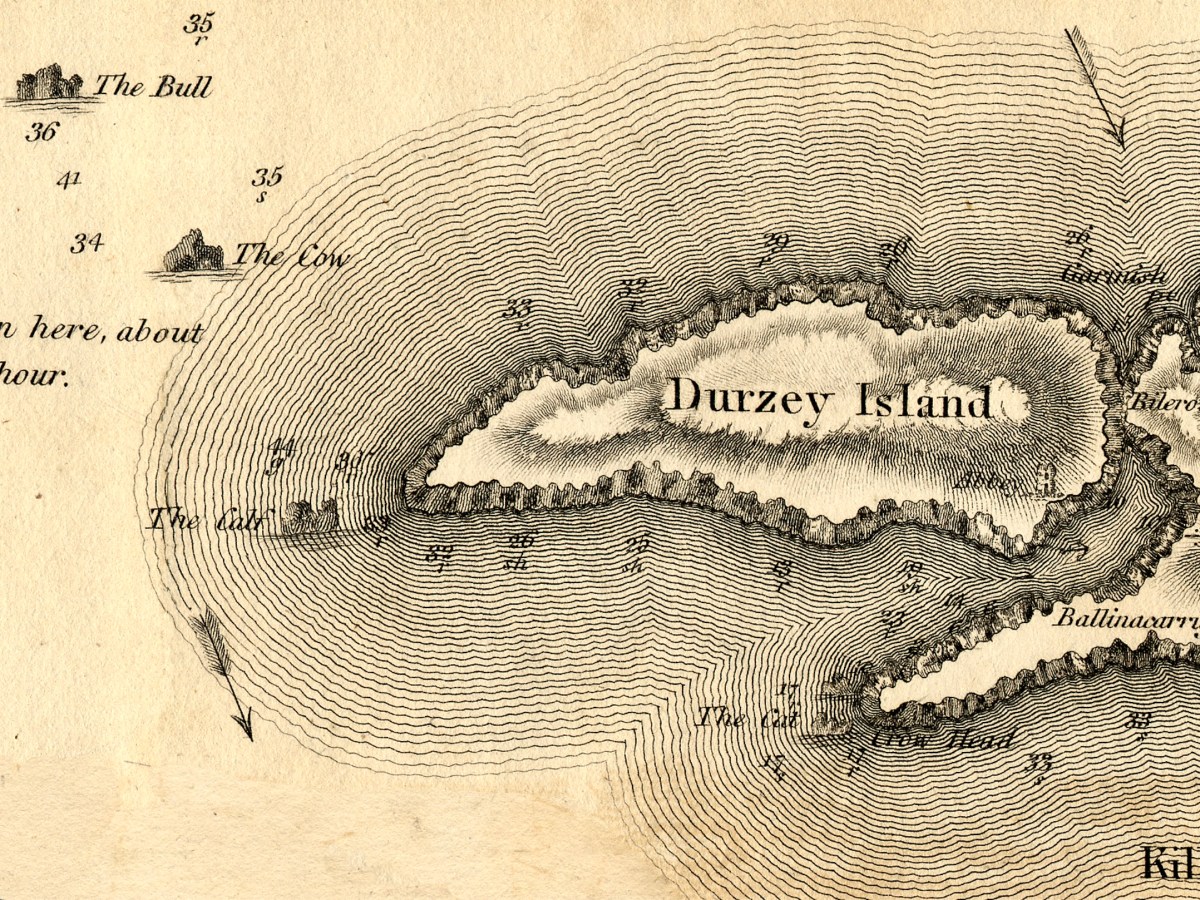

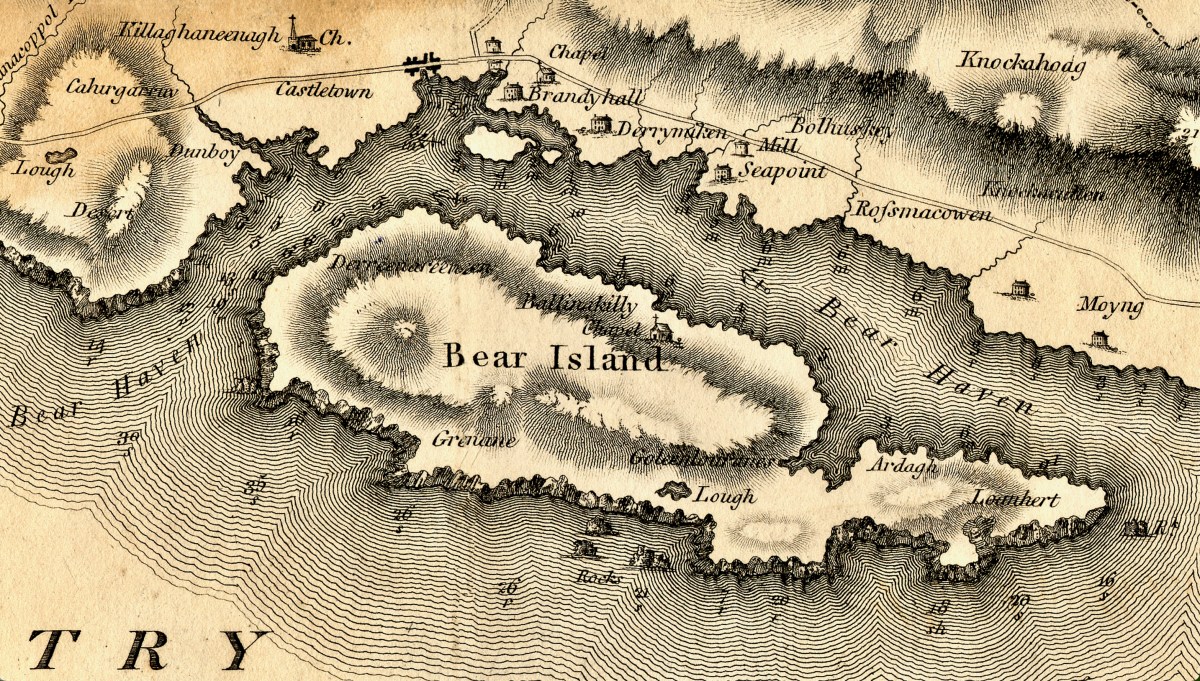

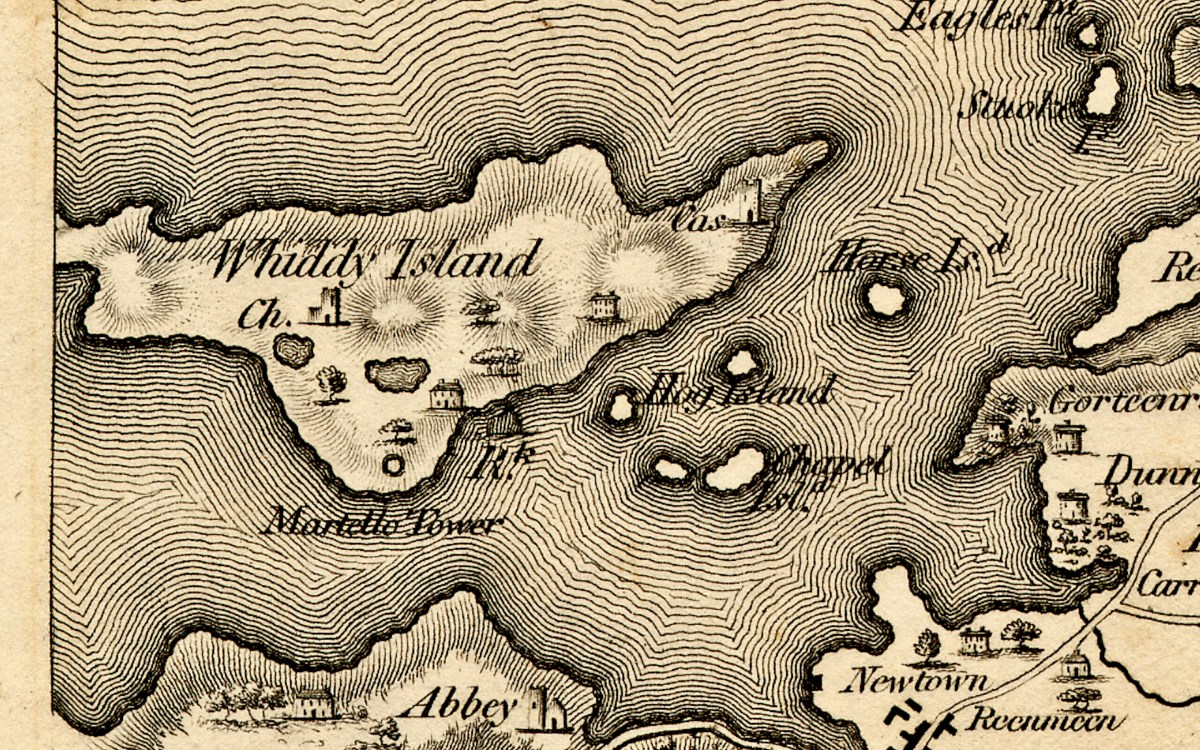

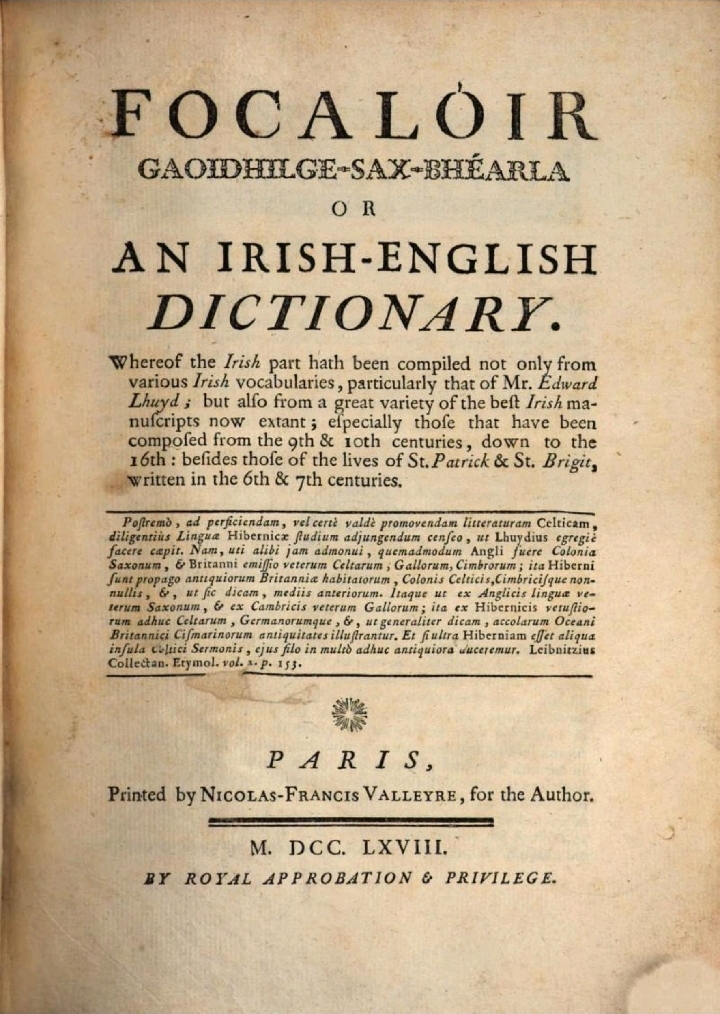

The second part of Vol I begins with just such a treatise: Dissertations on the National Customs and State laws of the Ancient Irish. However, although no author is given, implying this was Vallancey’s work, in fact it was written by John O’Brien, Catholic Bishop of Cloyne and Ross from 1747 to 1767, and originally titled A Critico-Historical Dissertation concerning the Antient Irish Laws, or National Customs, called Gavel-Kind, and Thanistry, or Senior Government. O’Brien was a considerable scholar, author of one of the earliest Irish-English Dictionaries (below). [Most of the illustrations in this blog post are not from the Collectanea.]

Although this is all about gavelkind – the Irish custom that dictated how land was divided between male heirs, the first section is devoted to how succession works in various countries (much talk about the Franks) and to the exclusion of daughters from succession and inheritance. Yes – those of you who think that women had more agency and autonomy in ancient Ireland than in other cultures, should bear in mind that this was a deeply patriarchal society. Here’s what O’Brien has to say about succession and property rights for women:

No inasmuch as I have treated the good old ladies of antient times with all the severity of the primitive maxims by excluding them from the enjoyment of all landed properties, it is fit and decent, that before I take my leave, I should provide for them otherwise in some becoming manner; their fortunes and natural establishments were not the less secure for such an exclusion, they were under no necessity of providing a marriage portion to attract courtiers, or satisfy husbands; on the contrary their husbands were obliged to portion and endow them according to the wise maxims of the primitive times, and without this condition they could obtain no female conforts. Women were therefore as earnestly courted and demanded in disinterested marriage in those days, as they are now haunted and in some countries run away with for their fortunes, more than for any conjugal affection. And hence we may assure ourselves the unfortuned good women of antient times found the marriage state much happier, then some of our modern ladies find it with all their thousands.

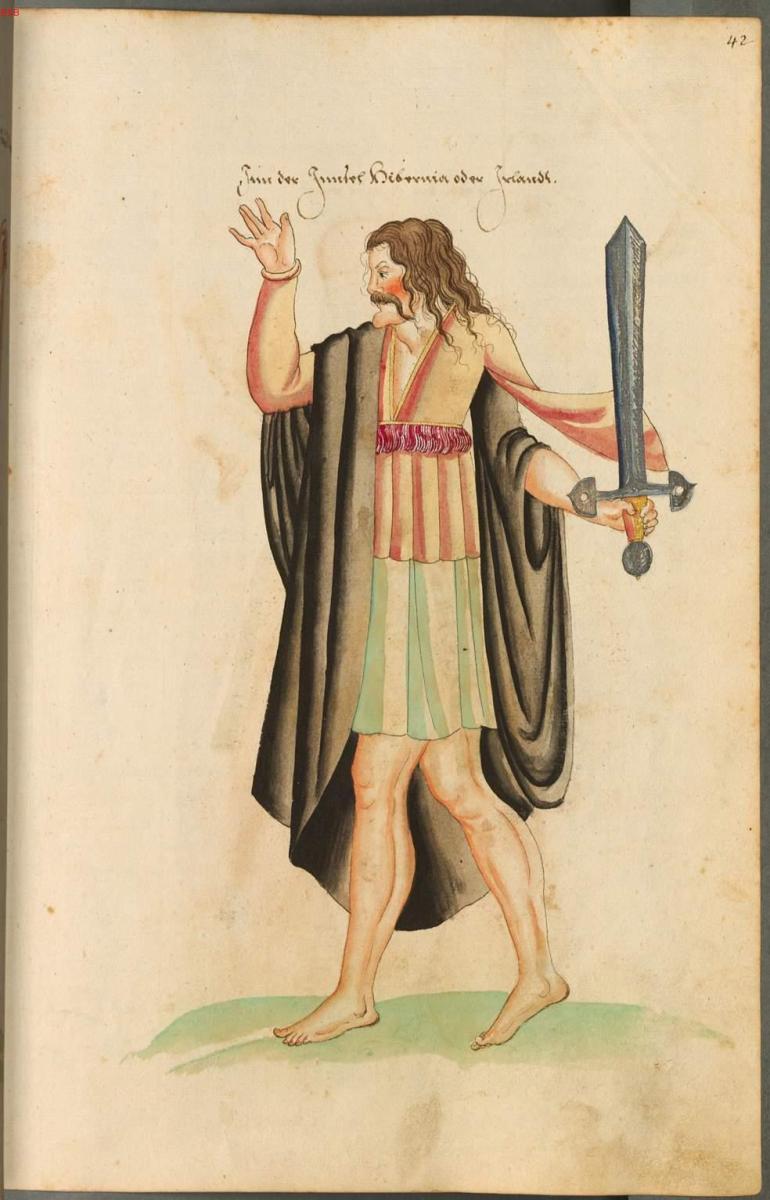

In short – the ladies, like the delightful one below*, should count themselves lucky!

He finally gets down to describing how gavel worked. Several forms existed but all consisted of dividing the property between sons or brothers. He asserts this was common in many countries – or antient lands – and also describes the practice of tanistry, whereby clan chiefs and their successors were chosen. Page after page is devoted to Scythians, Egyptians, Franks, Saxons, etc as precedents, showing it to be a common form of inheritance in the ancient world. This seems to be in service of counteracting the English prejudice agains it as barbarous and conflict-promoting. Clovis is mentioned, Gregory of Tours, the Visigoths and Vandals . . . O’Brien was obviously a man after Vallancey’s heart.

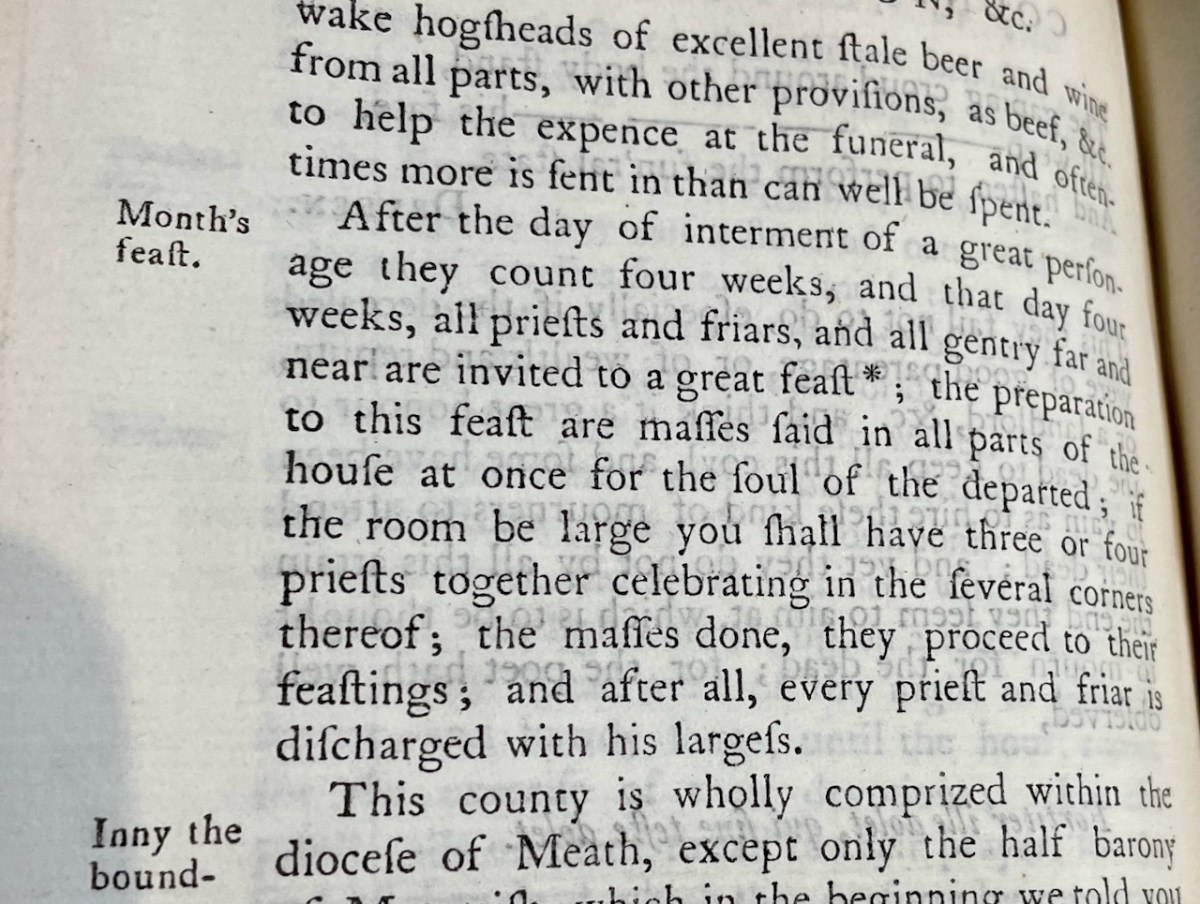

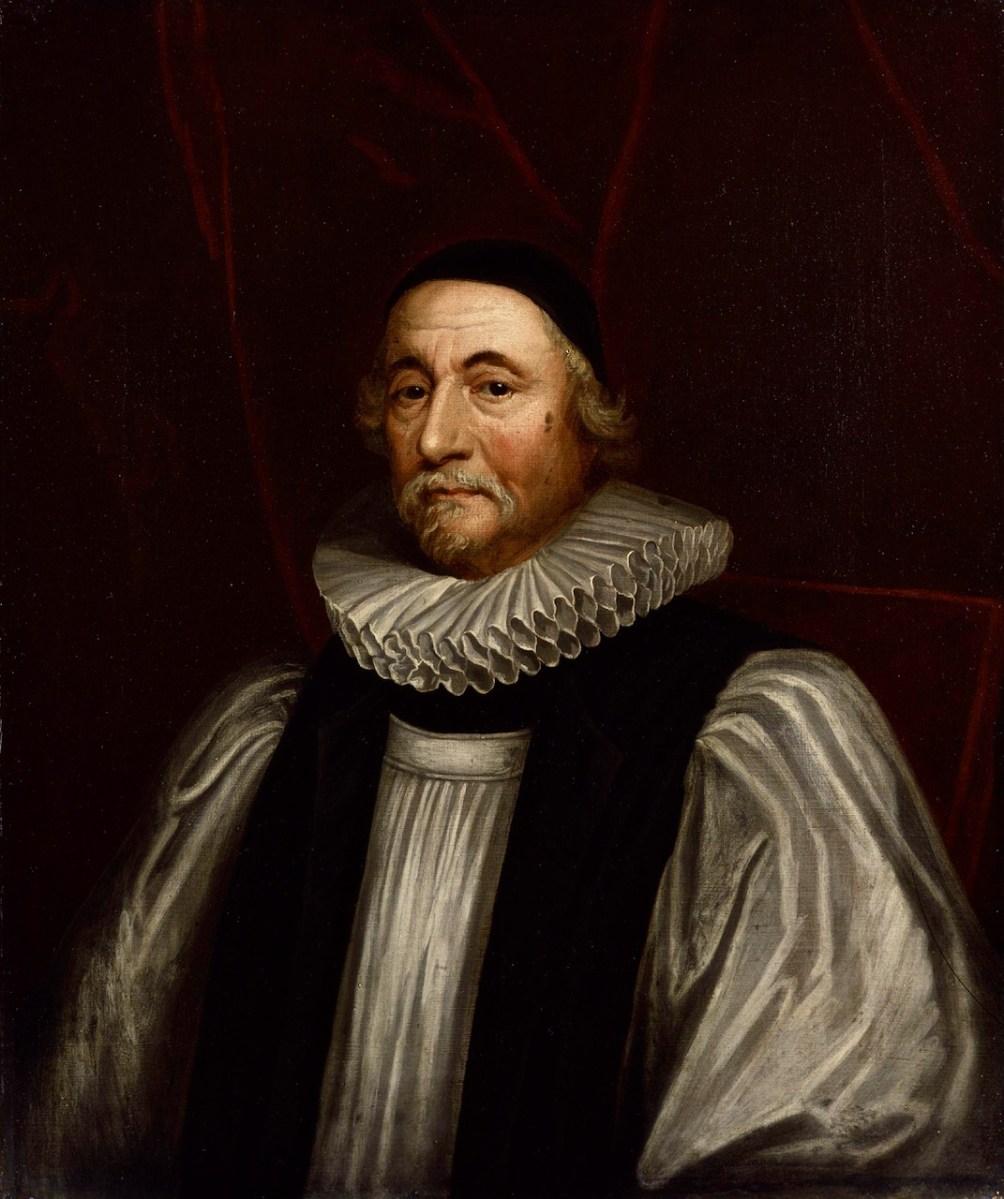

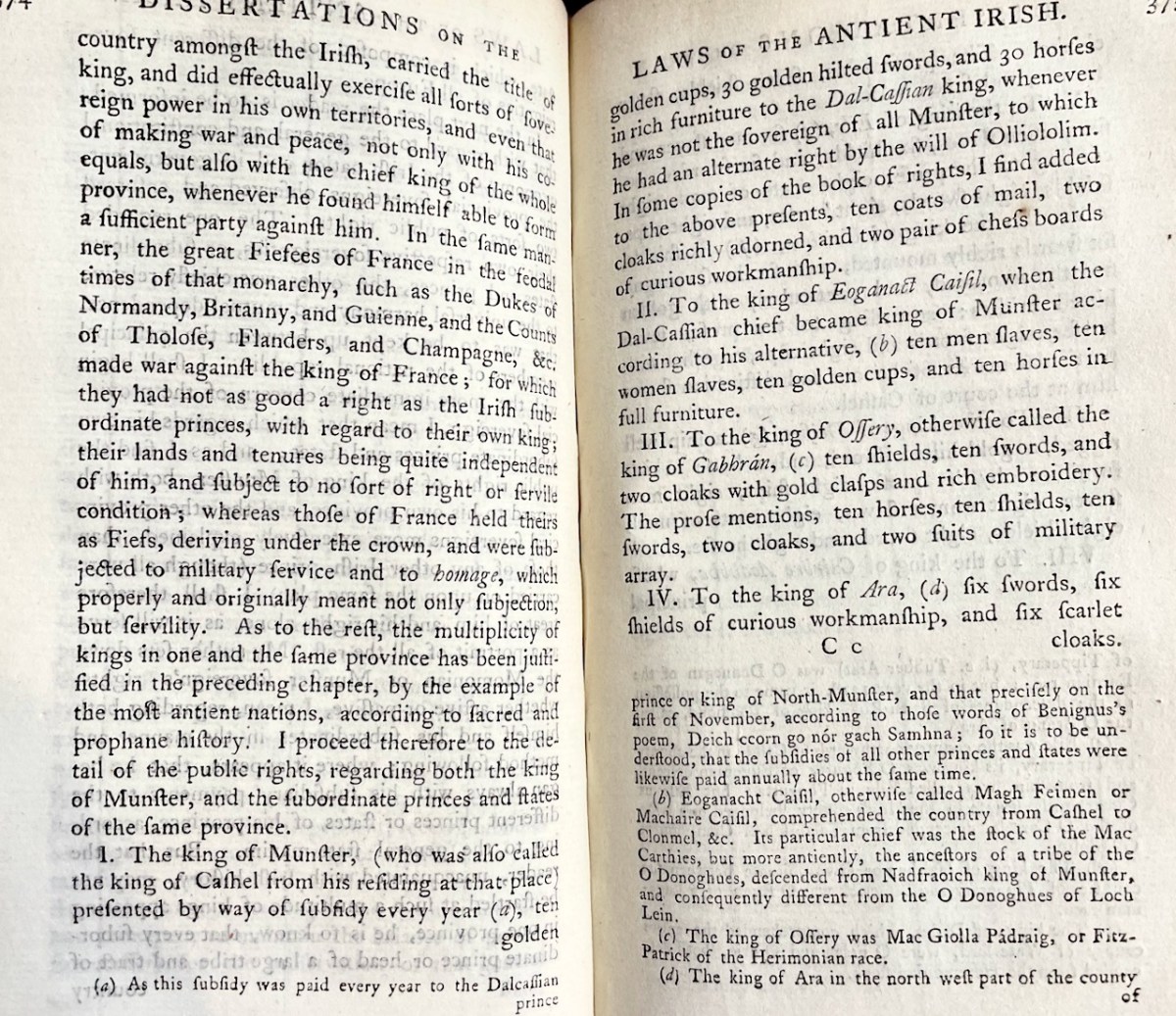

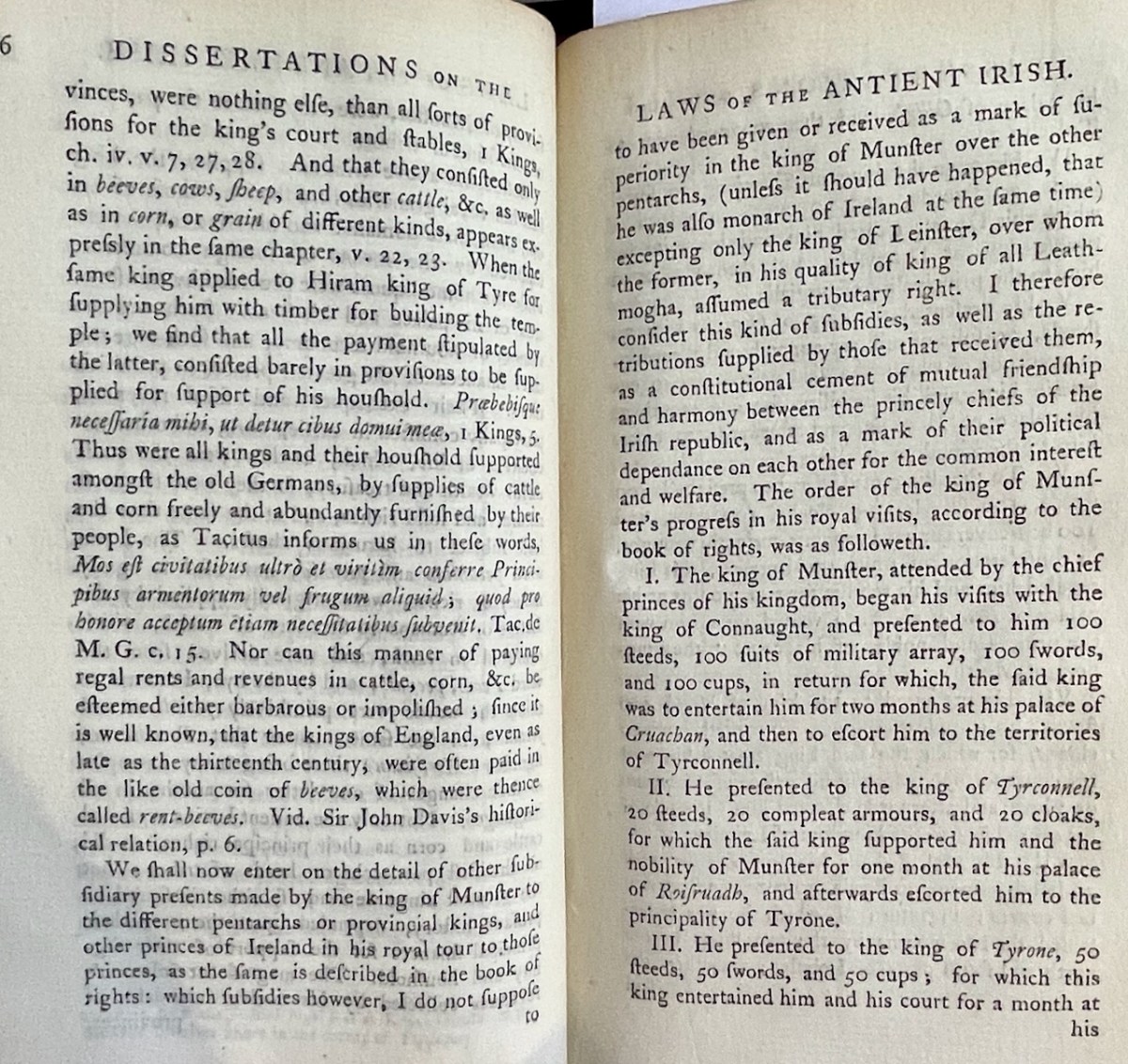

Chap 2 deals with all the tributes due to the king or chief (Above*) and his fiscal rights. The king or chief was NOT king or chief until inaugurated. I was surprised to find that the traffic went both ways – the king bestowed gifts on the chiefs within his sphere of influence and received tribute from them in turn.

For example the King of Munster (or Cashel) paid to the Dal-Cassian king

10 golden cups, 30 golden-hilted swords, 30 horses in rich furniture, 10 coats of mail, 2 cloaks richly adorned, 2 pairs of chess boards of curious workmanship

Another one mentions

10 men slaves, 10 women slaves,10 golden cups, 10 horses in full furniture

The King of Cashel, in return, received from his subject chiefs large gifts of livestock – bullocks, milch cows, hogs, weathers and beehives, along with, for some reason, many cloaks, some specifically described as scarlet.

The King also paid visits to other kings, as a constitutional cement of mutual friendship and harmony between the princely chiefs of the Irish republic (sic), and as a mark of their political dependence on each other for the common interest and welfare. The photo above sets out some of those kingly visits and what was involved for the visitor and the host. Lots of mentions of cups – perhaps like this one from the Hunt Museum Collection?

The second part of this Treatise is essentially a history of the O’Brien’s of Munster, offered as an illustration of the laws of Tanistry. It certainly offers many examples of conflict and treachery in the line of succession! And once again it wanders all over Europe and the ancient world as it traces the origin of the practice

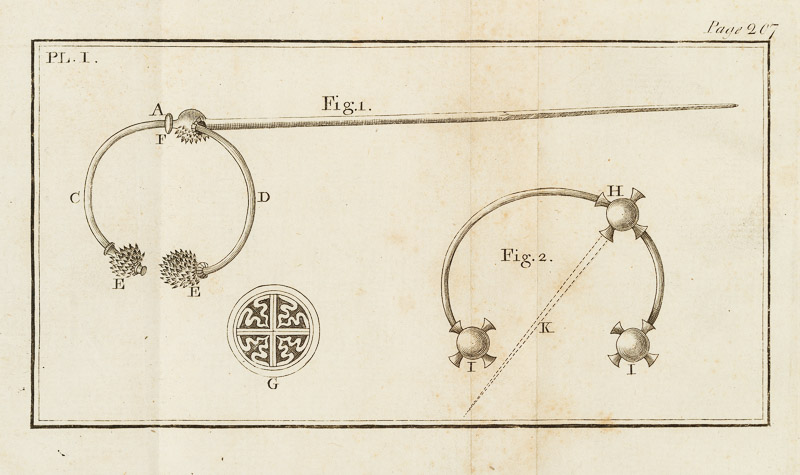

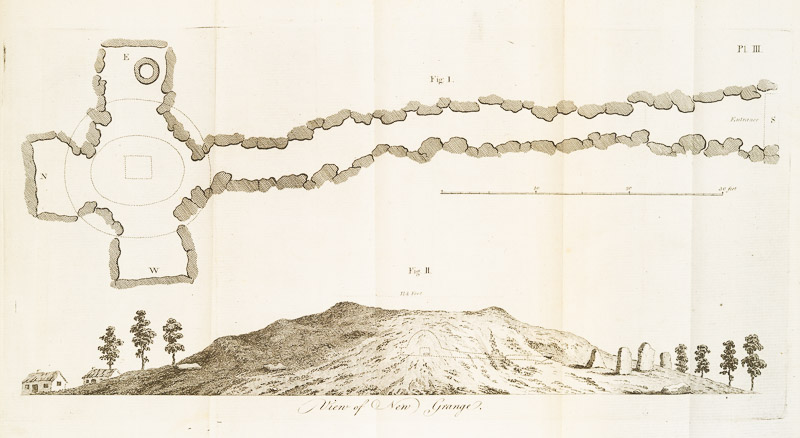

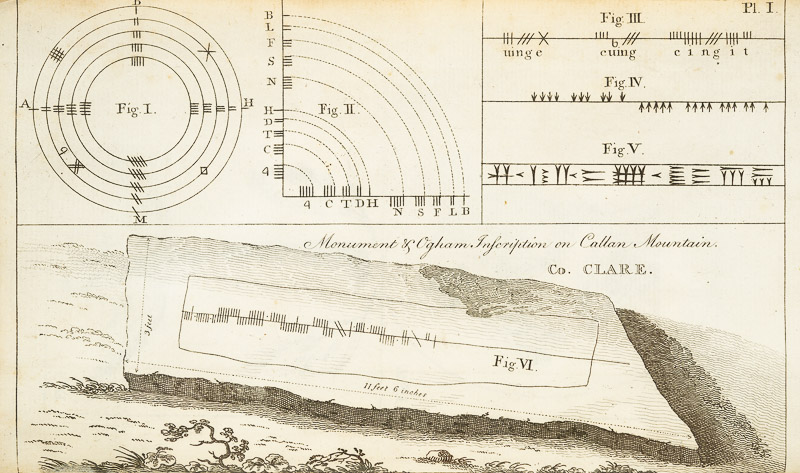

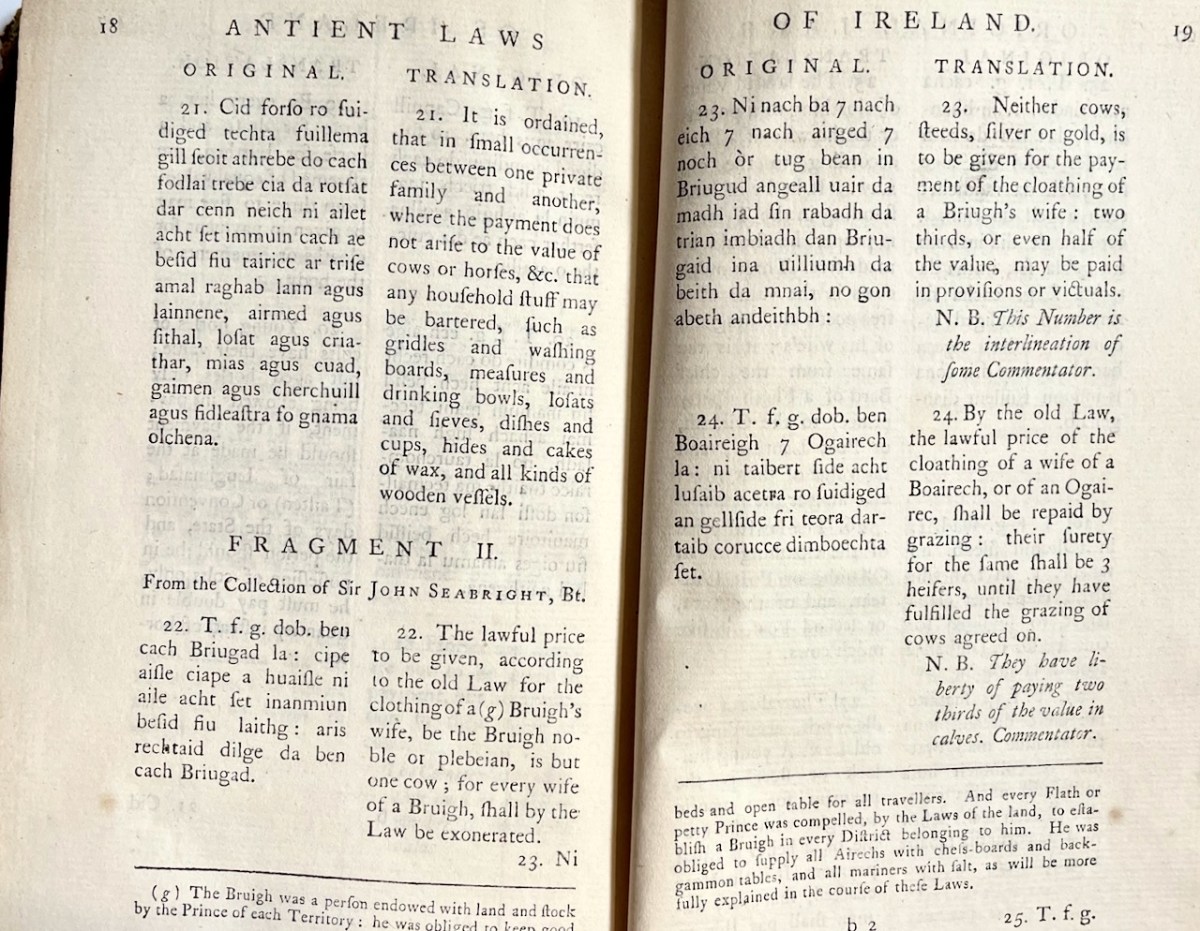

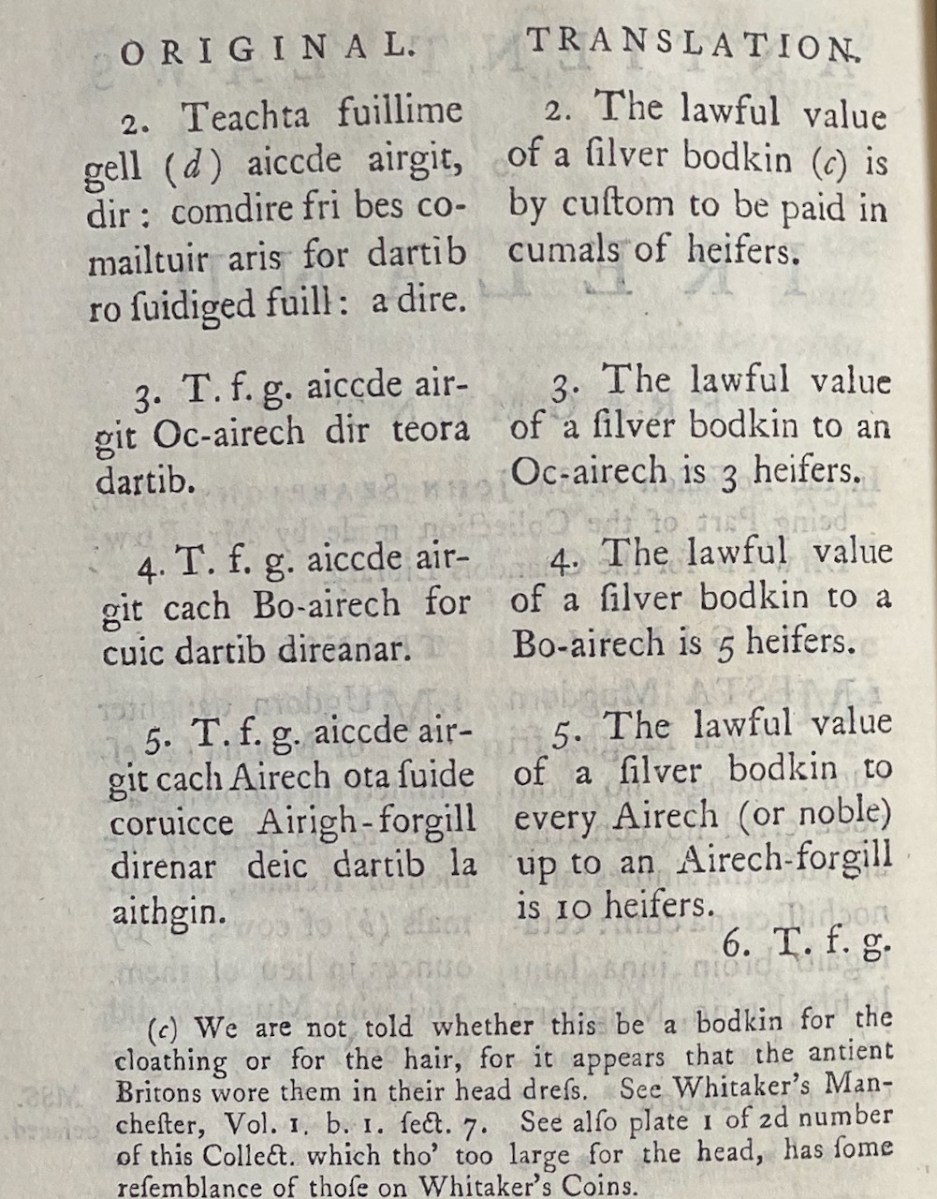

The final, and most interesting part of Vol 1 is about the Brehon Laws. This part indeed may have been by Vallancey. It consists of a number of fragments (above and below), originally collected by Edward Lhwyd (1660-17090, below) one of the earliest antiquaries to visit Ireland, document ancient sites and collect textual material.

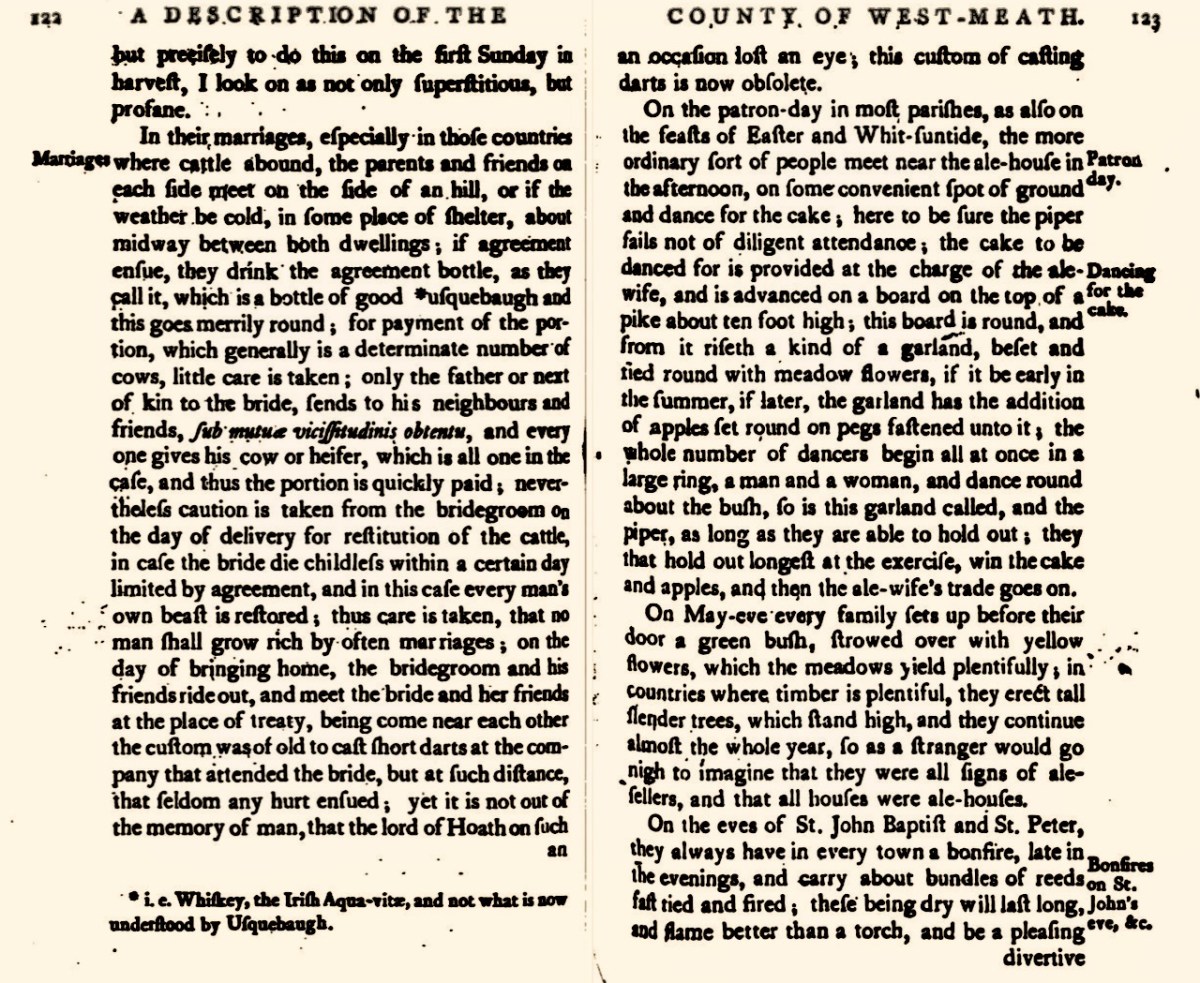

The section consists of individual laws, mostly pertaining to the value and goods and therefore the fines that were to be levied if something was stolen.

My favourites of these has to do with the value of the clothing of a poetess or the wife of a bard – three milk cows, apparently. However, if the clothing is embroidered the value goes up. For work properly done and completely finished, the reward is an ounce of silver. More is to be paid for extraordinary work in proportion. However, beware – if she be divorced for adultery this law is reversed and the woman must pay two thirds of the said value.

Having spent so much time on Vol 1, I am going to gallop, if I can, through Vol II. It starts with an essay called Brehon Laws and Gavel Kind Explained. This is mainly a defence agains the accusation by English of ‘barbarous’ customs’ and dwells on obscure points of orthography, such as when the letter P was introduced to Irish. It also deals with more of the practice of gavelkind, the exclusion of women, where else it was practiced and uses the marvellous term Strongbonian for the Anglo Norman settlers.

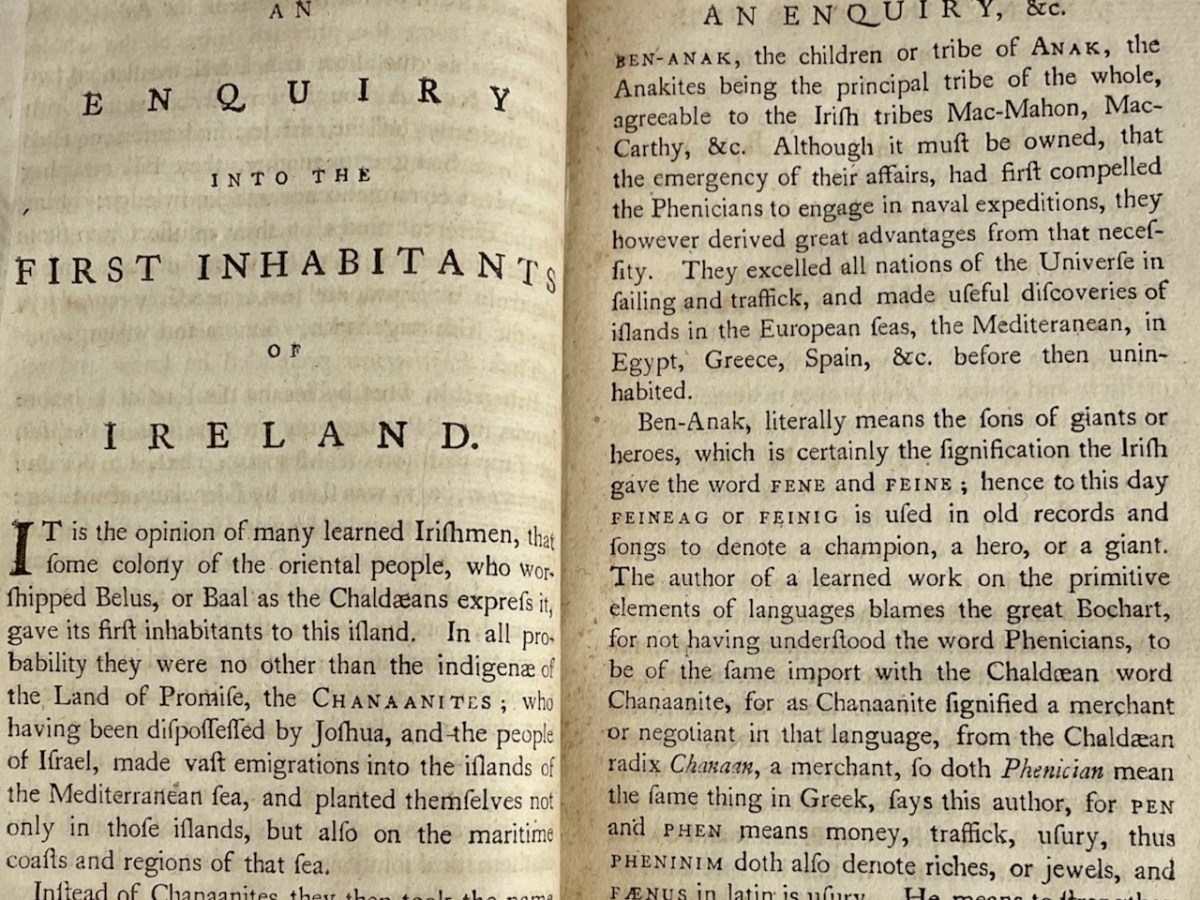

An Inquiry Into the First Inhabitants of Ireland follows. This is where Vallancey introduces his claim that the first Irish Irish were Phoenicians. I have dealt with this in the first post so I will not cover this in detail.

The next section was written by Edward Ledwich another of the early Irish antiquaries – see my post on the marvellous Monaincha for more about Ledwich. What’s fascinating about this is that Ledwich and Vallancey were subsequently at war with each other and Ledwich had views that were just as biased and erroneous as Vallancey’s.

For more on Ledwich see the The Dictionary of Irish Biography entry, which has this to say:

Ledwich afterwards openly and very strongly opposed Vallancey’s views on ancient Irish history, particularly his beliefs about the Phoenician origins of the Irish people. Ledwich was convinced that the ancient Irish had been as barbarous as the scanty Greek and Roman descriptions suggested; that they originated in Scandinavia; and that English colonisation had brought to the island such civilisation as it had subsequently enjoyed. Both Vallancey and Ledwich, along with Charles O’Conor (qv) of Belanagare and William Burton Conyngham (qv), were founder members (1779) of the Hibernian Antiquarian Society, which collapsed in 1783 in the bitter disagreements between Vallancey and Ledwich.

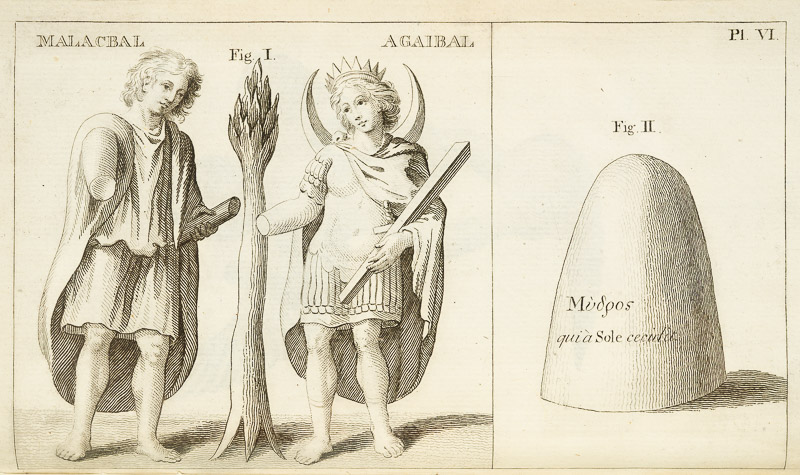

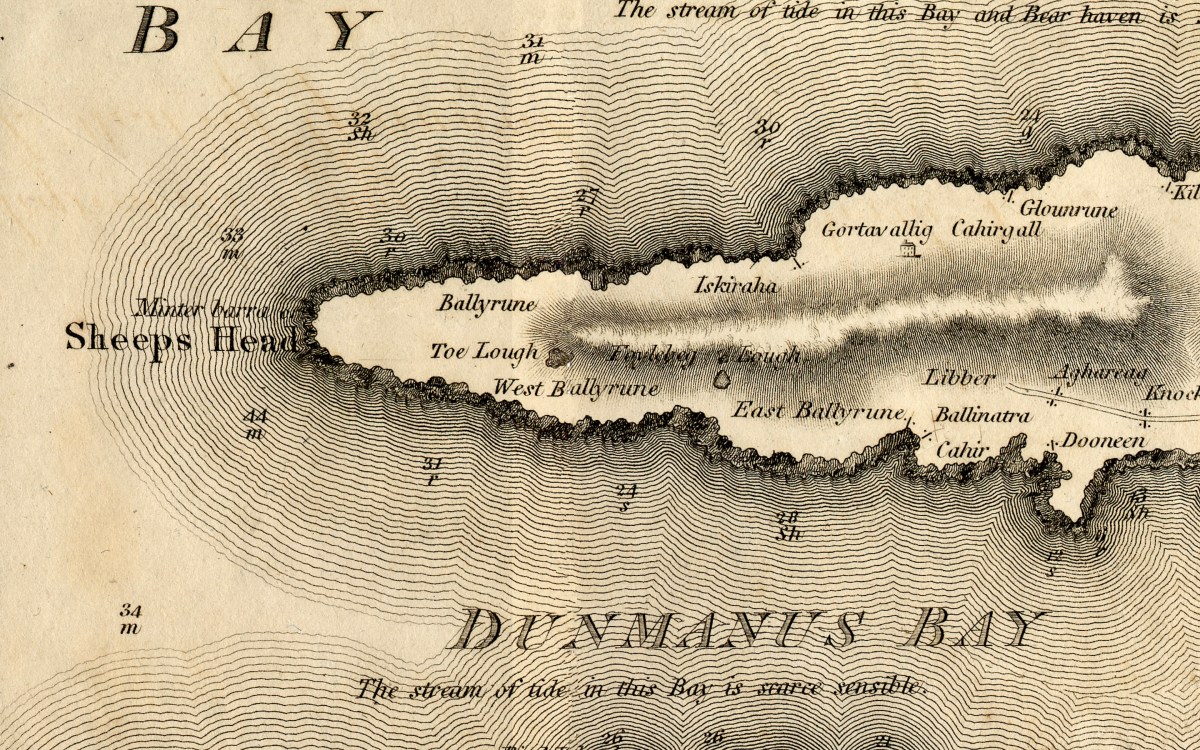

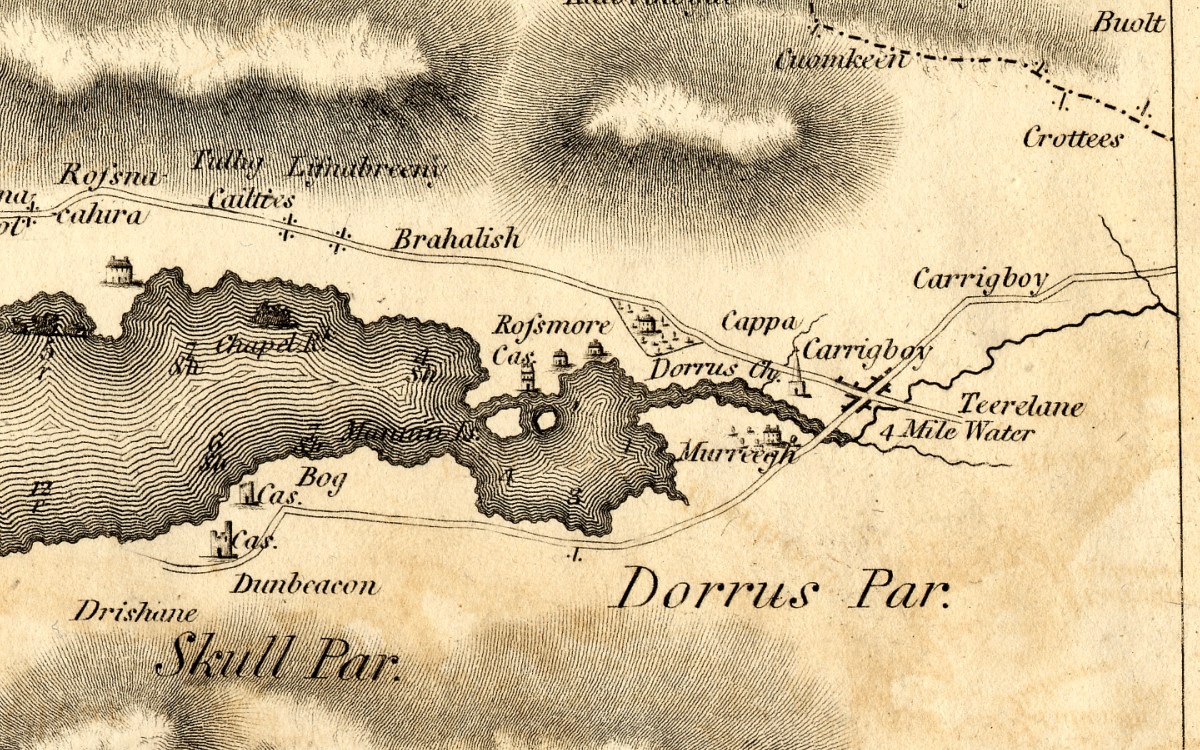

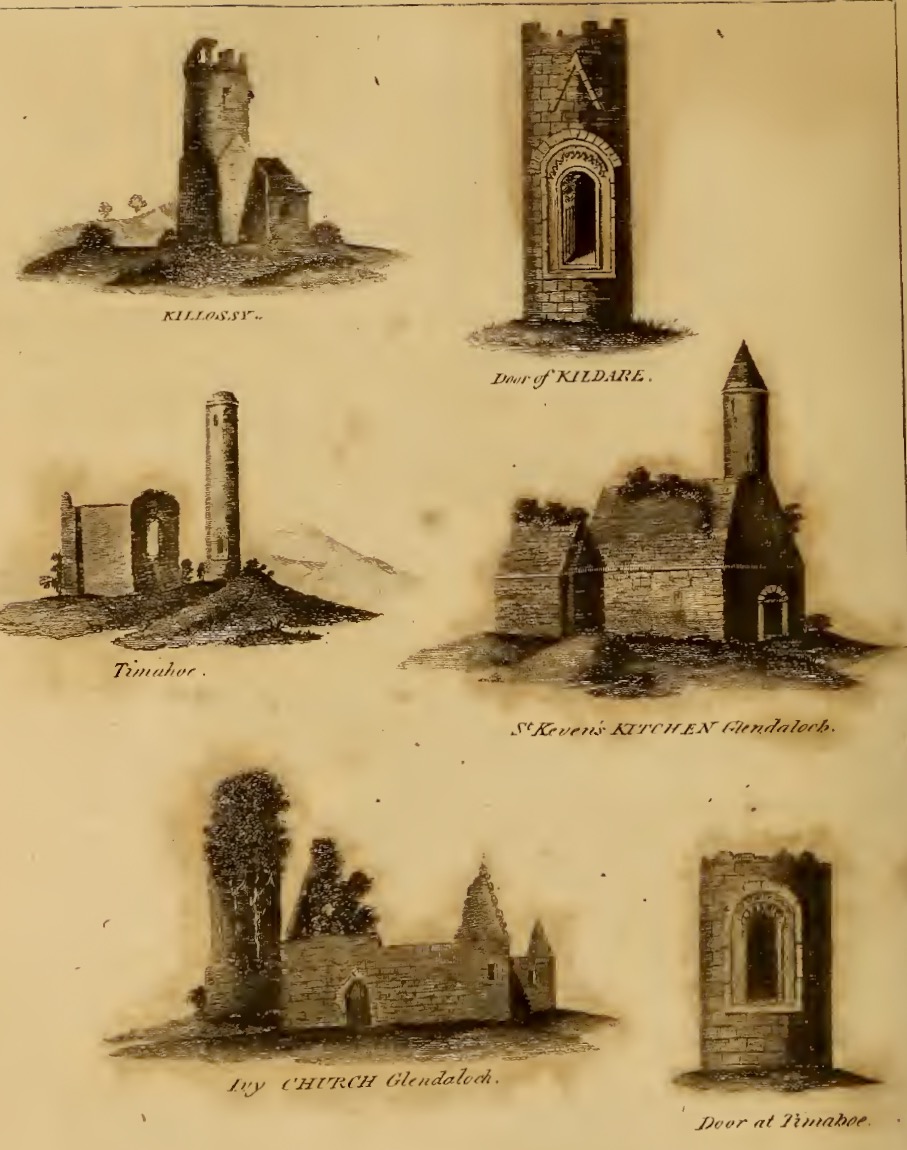

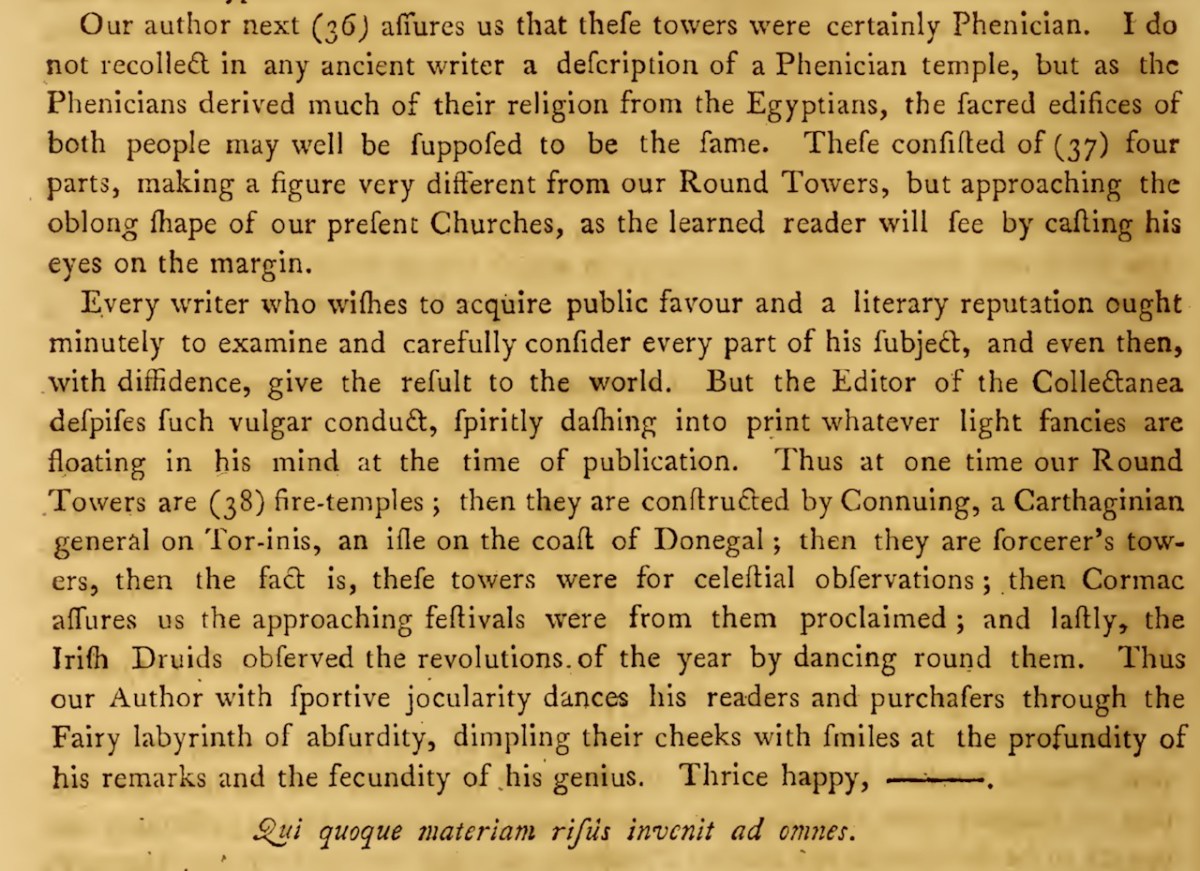

The piece on round towers was written by Ledwich, (although these illustrations are from his later Antiquities of Ireland) presumably before the great falling out between the two men. Whereas Vallancey saw round towers as observatories for an astral, or sun-worshipping, cult that had been brought to Ireland by the Phoenicians, Ledwich believed that the round towers were Danish works. In fact, he was as obsessed with the Danes as Vallancey was with the Phoenicians. They were built, he says as ‘watch towers against the natives’, thus neatly upending the most common belief in Ireland about round towers – that they were watch towers against Viking Raids. (In fact they were bell towers, but that’s another story.) Here, Ledwich obliquely refers to Vallancey’s work that towers were erected by Phoenicians and says ‘this description is plainly the work of fancy’.

Ledwich was convinced that nothing of any architectural value could have been constructed by the Irish themselves. Reading his argument (and Vallancey’s) I was struck by how it foreshadows the pseudo-archaeolologists who claimed that big impressive monuments must be the work of superior races – people like Von Daniken in his Chariots of the Gods in the 60s who assigned them to aliens, or more recently the conspiracy theorist, inexplicably given a platform by Netflix, Graham Hancock. Hancock’s series Ancient Apocalypse tries to find a race of Ice Age people who must have constructed many of the ancient monuments (or even odd geographical features) around the world. Hancock (‘I’m just asking questions’) is a true inheritor of the nuttiness and hubris of both Vallancey and Ledwich. Later, Ledwich felt sufficiently incensed by Vallancey’s theories to say this, in his Antiquities of Ireland:

No wonder they were at war! Can anyone translate the Latin? I suspect it’s a further insult. I do absolve Vallancey, by the way, of the baser motivations visible in Ledwich and Hancock – that is, a racist and colonial ideology that sees indigenous people as incapable of building impressive monuments. No – Vallancey had no difficulty at all in promoting the ancient Irish as one of the great and noble races.

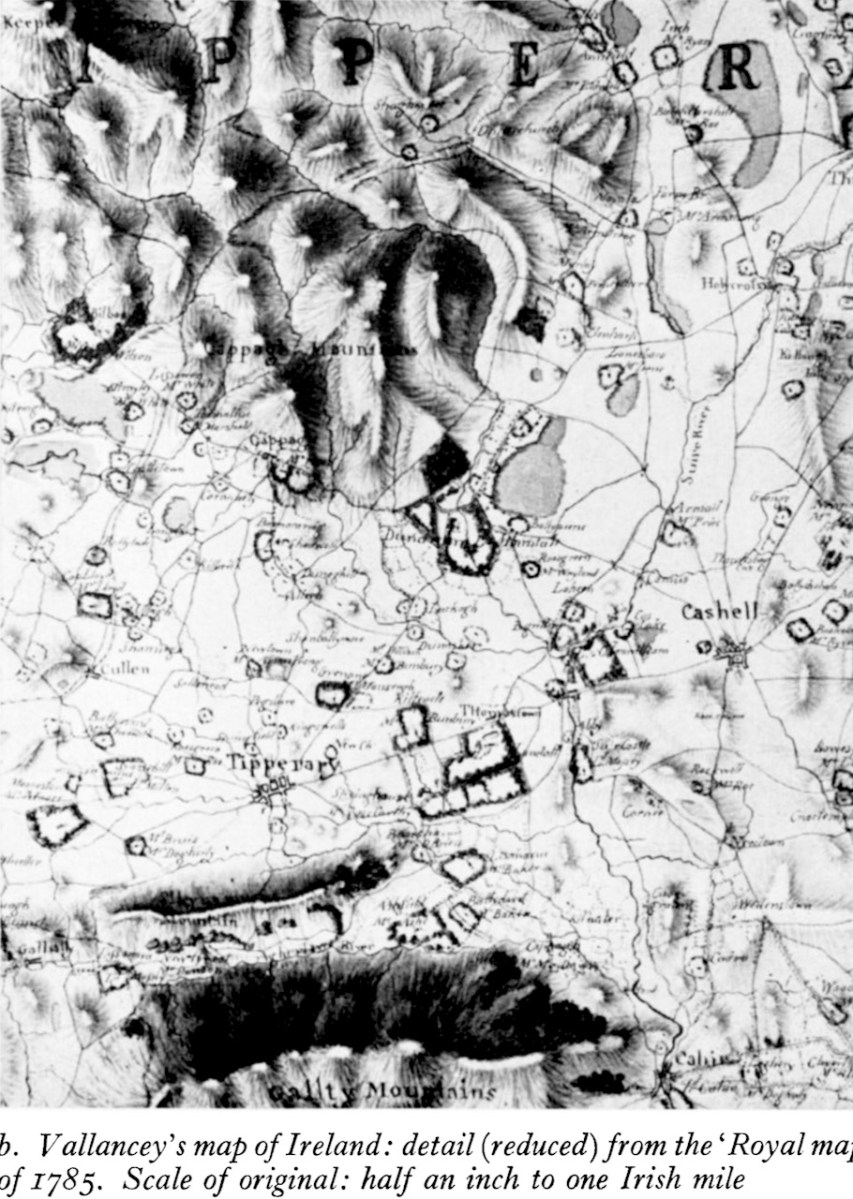

I’ll leave you with this view of Cashel from Ledwich’s Antiquities of Ireland. Despite all my best intentions of getting through several volumes, I am still only half way through Vol 2 of 5. Any suggestions, dear readers, on how I can wrap this up so that I can get my life back?

*Kostüme der Männer und Frauen in Augsburg und Nürnberg, Deutschland, Europa, Orient und Afrika available here.