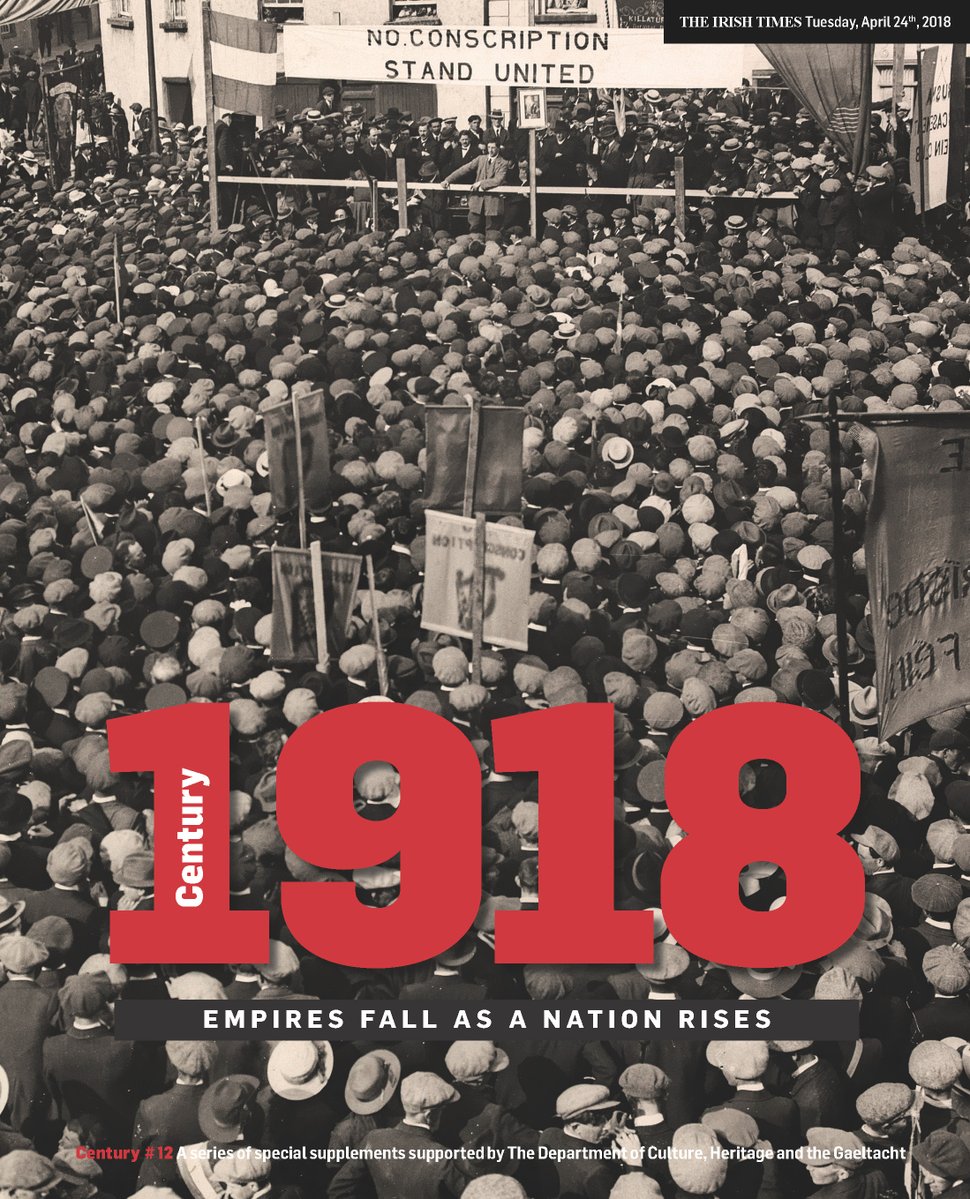

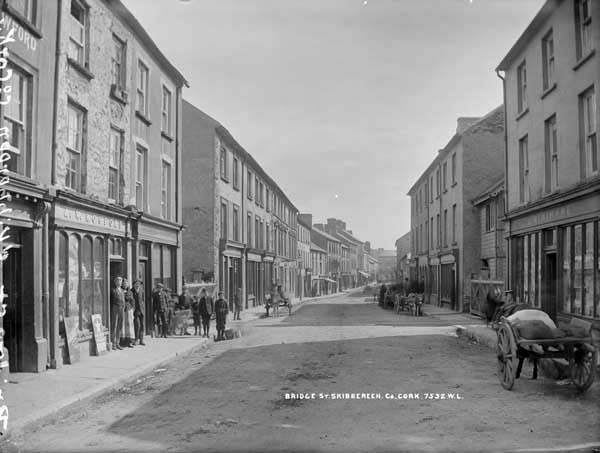

This week, I was thrilled to hear Met Éireann announcing that the first storm of this year will be called Storm Agnes, after Agnes Mary Clerke who grew up in Skibbereen (in the pink house, below) and went on to become the foremost science writer of her day and a distinguished astronomer.

I’ve been writing and giving talks about Agnes since 2015, and it’s wonderful that she is becoming more of a household name now. Storm Agnes is especially fitting because she certainly shook up the Astrophysics establishment in her day, as a woman writing about what had traditionally been a man’s domain. The post that follows is a substantial re-writing of my 2015 post From Skibbereen to the Moon: Agnes Mary Clerke. I know a lot more about Agnes now than I did then. Mostly, that’s down to the work of Mary Bruck, a fellow astronomer, yet another Irish woman (from Meath) and author of Agnes Mary Clerke and the Rise of Astrophysics.

West Cork is where Agnes grew up, with her parents, sister and brother. Agnes, Ellen and Aubrey were all brilliant, scholarly and published writers, each in their own fields. Their father, John William Clerke came from a long-established ‘Liberal Protestant’ family in Skibbereen – that’s John William’s own father, St John Clerke’s, grave in Skibbereen, above. At the time the children were young he was the manager of the Provincial Bank and the family lived above it.

Agnes was born in 1842 and her young life was dominated by the awful tragedy of the Great Famine, which started in 1845 and blighted life in Skibbereen up to 1850 and beyond. John William (above) headed up relief efforts in Skibbereen during this awful time and was felled by Famine Fever himself, remaining critically ill for months.

John had married Catherine Mary Deasy (above, in older age), the sister of his best friend at Trinity, Rickard Deasy, from a prosperous Catholic family in Clonakilty. Catherine had been well educated in the Cork Ursuline convent and was high-minded and musical. She tutored the children to a high proficiency in music, Latin and Greek. Catherine played Irish music on the harp and retained her ability to entertain well into her 80s.

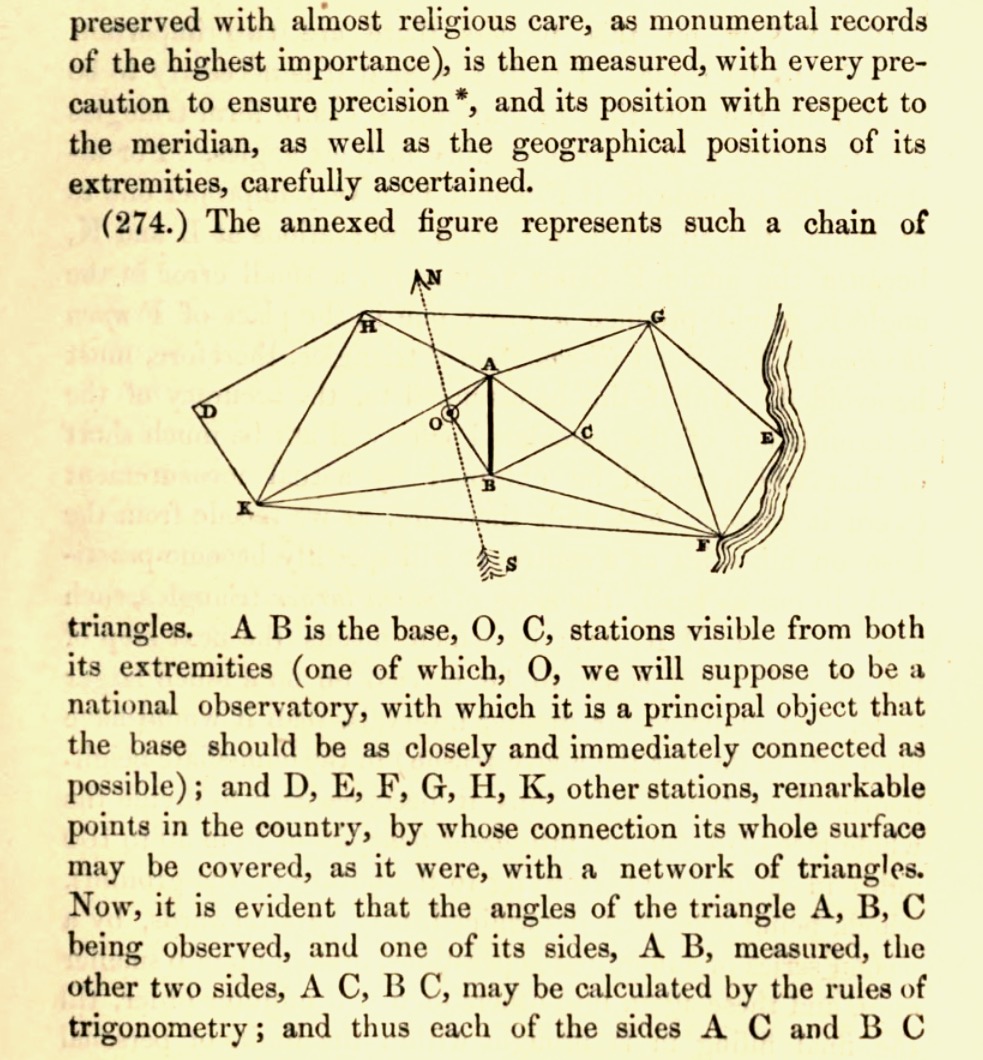

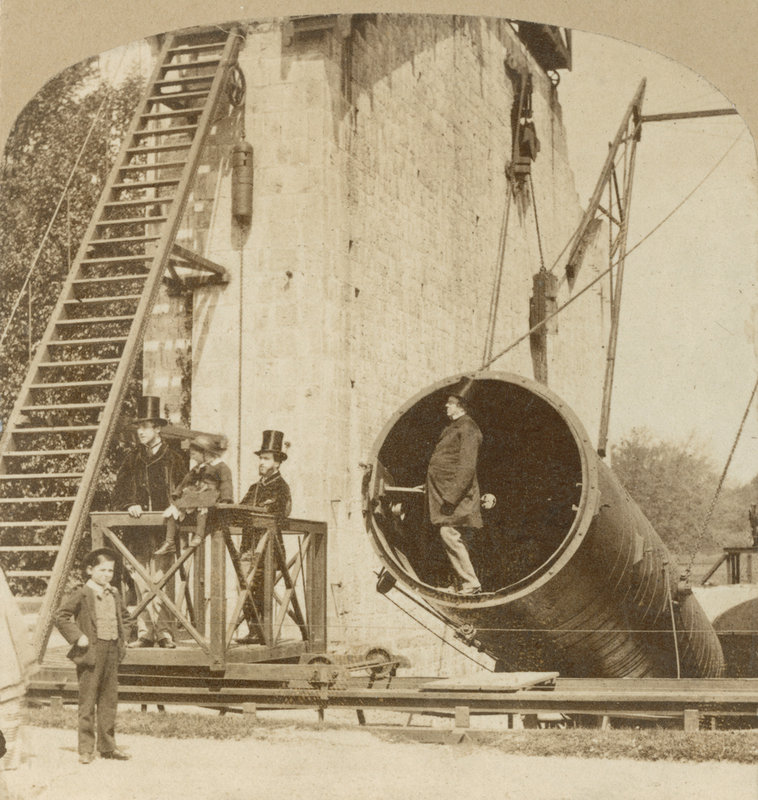

The children grew up in the 1840s and 50s with access to their father’s extensive library, his telescope (like the one above) and his chemistry experiments. The telescope, according to Mary Brück’s biography, was equipped with a chronograph for timing the transits of stars across the meridian. With this arrangement Clerke was able to provide a time service for the town of Skibbereen, which was as yet unconnected to the outer world by either railway or telegraph.

Insatiably curious, they devoured knowledge and by 15 Agnes had already begun to write a history of astronomy – a book that would later count as her magnum opus. By the age of 11, she had mastered John Herschel’s Outlines of Astronomy. (She was later to write the biography of Herschel’s father and aunt – still available for Kindle!). That’s a page from Outlines of Astronomy, below. To repeat – she was 11!

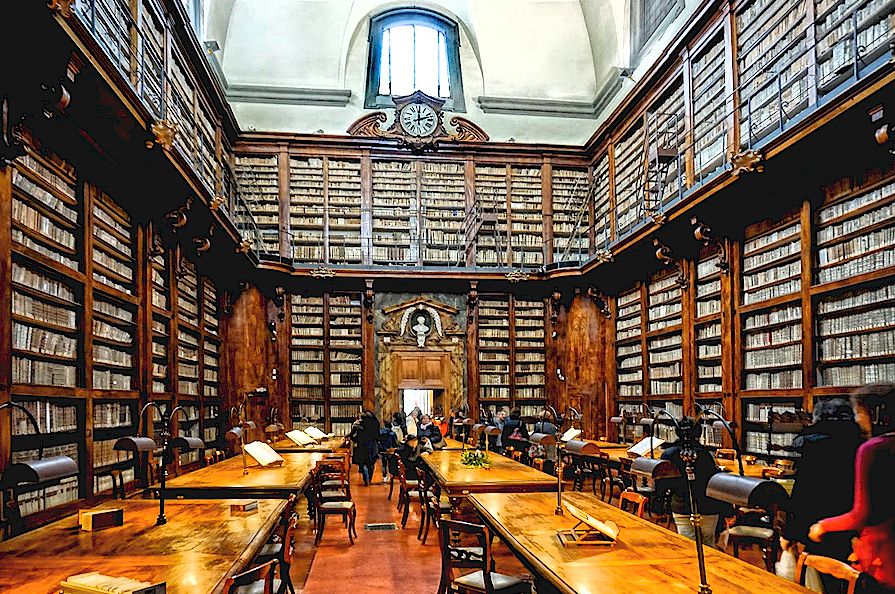

The family moved to Dublin when Agnes was 19 – her father had been appointed to a position by Rickard Deasy who was now Baron of the Exchequer Court. But her health was always delicate and her mother determined to move the two young women to a more salubrious climate. Starting with extended visits and then moving there, the Clerke women spent from 1867 to 1877 in Italy.

There, Agnes and Ellen, now in their 20s and early 30s, studied extensively in the excellent libraries in Rome and Florence (above), becoming proficient in several languages and going to primary sources to research their interests.

Thereafter, the family settled in London, at 68 Redcliffe Square (below). Devoted to each other, none of the siblings ever married and the family lived together in harmony and supported each other’s endeavours to the end.

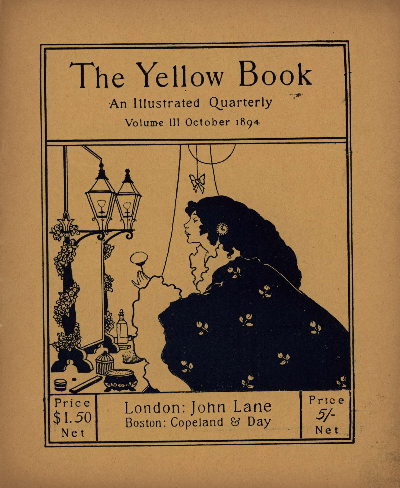

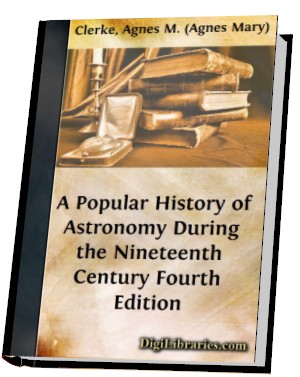

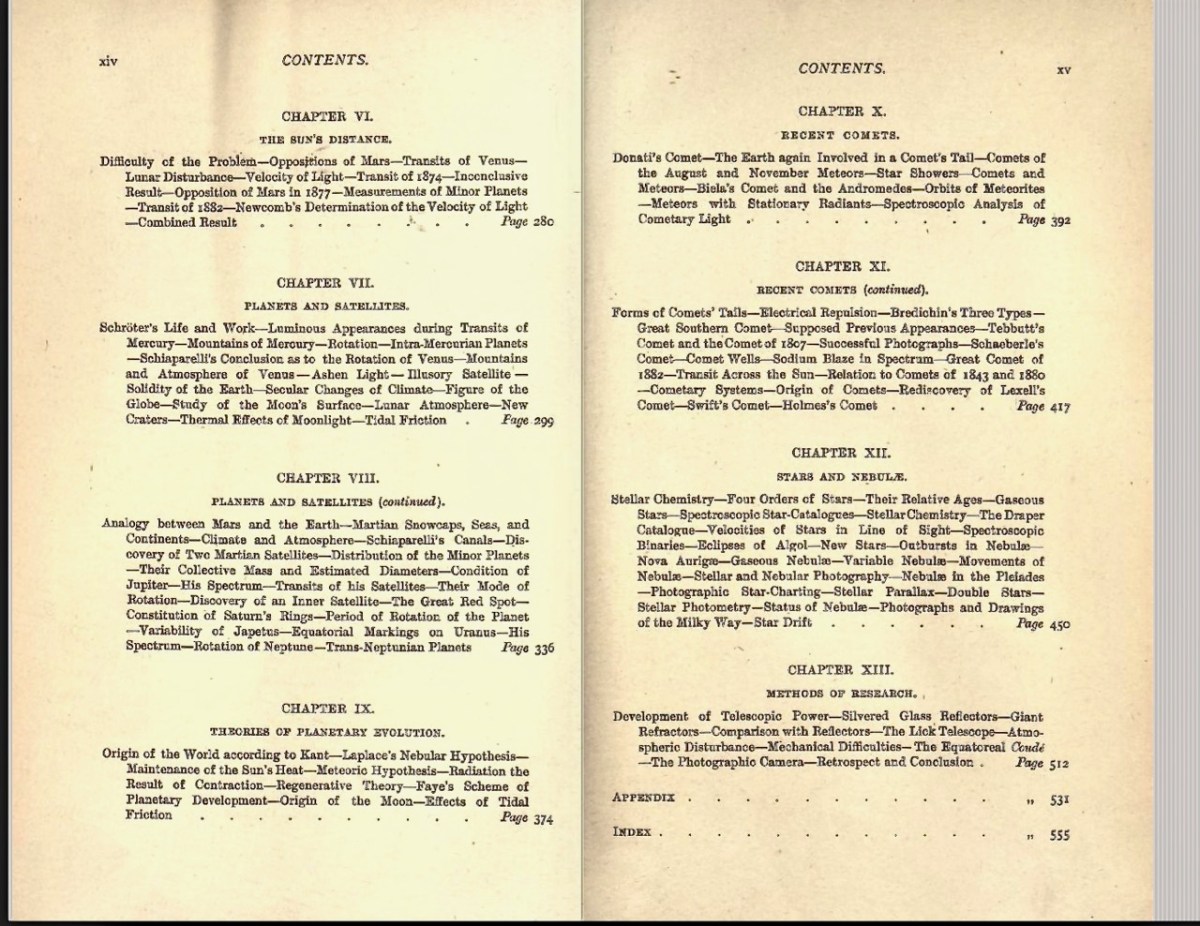

Although she started off with a wide range of topics, Agnes over time concentrated on writing about astronomy. Her first published pieces (one about Copernicus, the other about the Mafia!) appeared in the Edinburgh Review in 1873. But her magnum opus, the book which brought her to the attention of the scientific community in England and the United States, was her History of Astronomy during the Nineteenth Century.

With it, she burst upon the scene in December 1885. She had spent four years writing it. It was an instant best seller – both to interested lay people and amateurs but also to serious students of astronomy, as one reviewer put it on account of its accuracy and the really remarkable skill with which the leading points on which our knowledge has been increased are seized upon and set forth. It sold out in two months and went to a second printing and an American edition. It has never been out of print since. It is still used as a text book and on lists of recommended readings. It went into four editions, each one a monumental task to update as findings came thick and fast. Illustrations only began with the second edition.

Now in her early 40s, the depth and scope of Agnes’s scholarship is awe-inspiring. To read through the book (available online through Project Gutenberg) is to see a brilliant mind at work. Her purpose in writing it was:

to embody an attempt to enable the ordinary reader to follow, with intelligent interest, the course of modern astronomical inquiries, and to realize (so far as it can at present be realized) the full effect of the comprehensive change in the whole aspect, purposes, and methods of celestial science introduced by the momentous discovery of spectrum analysis.

This IS the rocket science of her generation, encompassing chemistry, physics, mathematics, history of scientific thought, cosmology, the most up to date observation and measurement techniques – in short, the disciplines that made up the emerging science of astrophysics. Take a look, for example, at the headings for her Chapter IV: Chemistry of Prominences—Study of their Forms—Two Classes—Photographs and Spectrographs of Prominences—Their Distribution—Structure of the Chromosphere—Spectroscopic Measurement of Radial Movements—Spectroscopic Determination of Solar Rotation—Velocities of Transport in the Sun—Lockyer’s Theory of Dissociation—Solar Constituents—Oxygen Absorption in Solar Spectrum. Looks pretty frightening for a non-scientist, doesn’t it? And yet, this book was one of the best-sellers of the day.

One of the huge advances in astronomy in the nineteenth century was the development of the spectroscope and Agnes’s book was the first widely-read description of its significance. A spectroscope disperses light over a much wider band than a simple prism. The pattern of colours, as well as black bands in the spectrum, all indicate the presence of certain elements. The composition of stars could now be studied for the first time.

Better optics was another huge advance. Lord Rosse of Birr Castle worked with Grubb (who had been at college with Aubrey) to develop the largest telescope then in existence, capable of analysing nebulae. Agnes has a chapter devoted to Rosse’s achievements. Agnes had a unique ability to absorb and compile knowledge and then to lay it out for the non-specialist. (I got through the first chapter with little difficulty.) She is rightly credited as the founder of what is called today Science Writing. Her books (she wrote many more) and articles sold well and she made a good living from her writing.

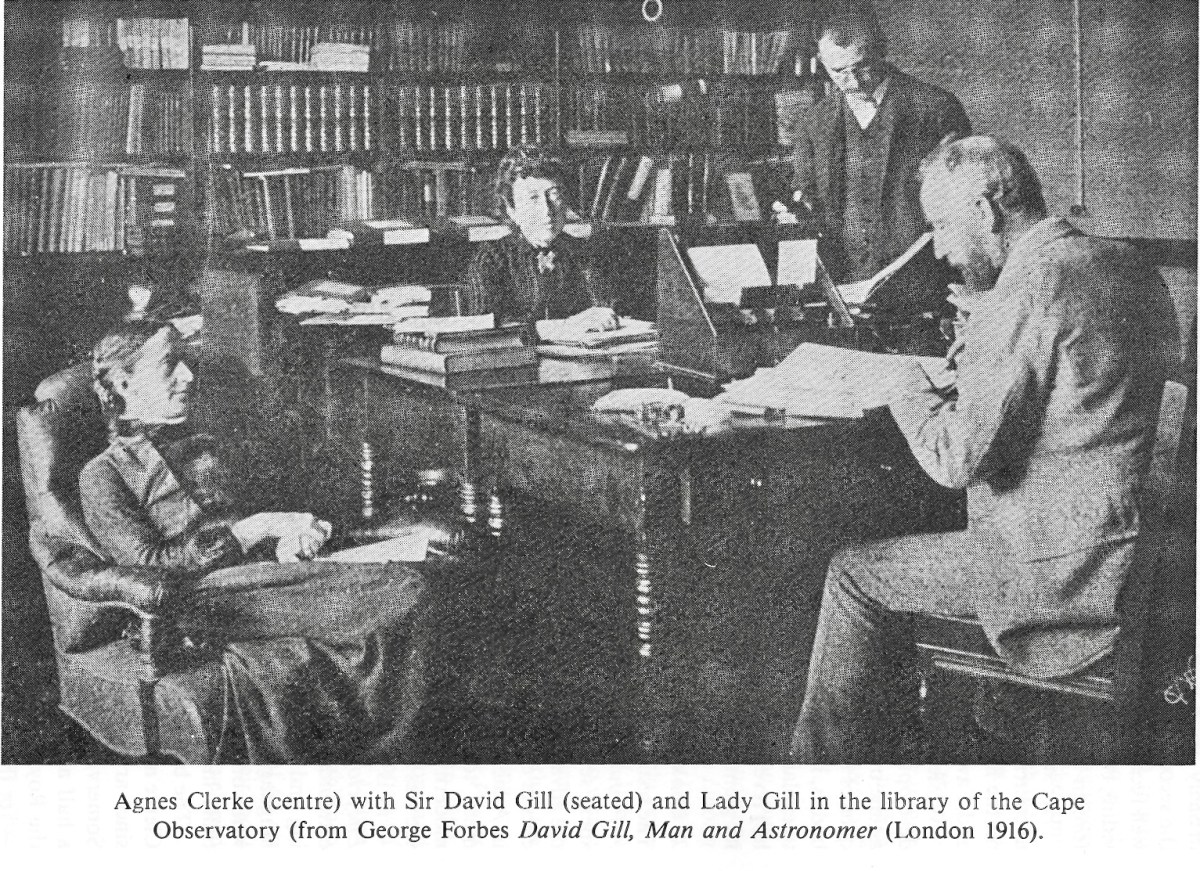

Successful as the book was, Agnes was a woman, and a non-practitioner (that is, she didn’t work in an observatory) and many in the predominantly male science establishment of Victorian Britain were sceptical of her knowledge and resentful at her success. One who was not was David Gill who invited her to spend time at his observatory in Cape Town. She went, had a marvellous time, and gained practical experience that enabled her to write with much more confidence on certain subjects afterwards.

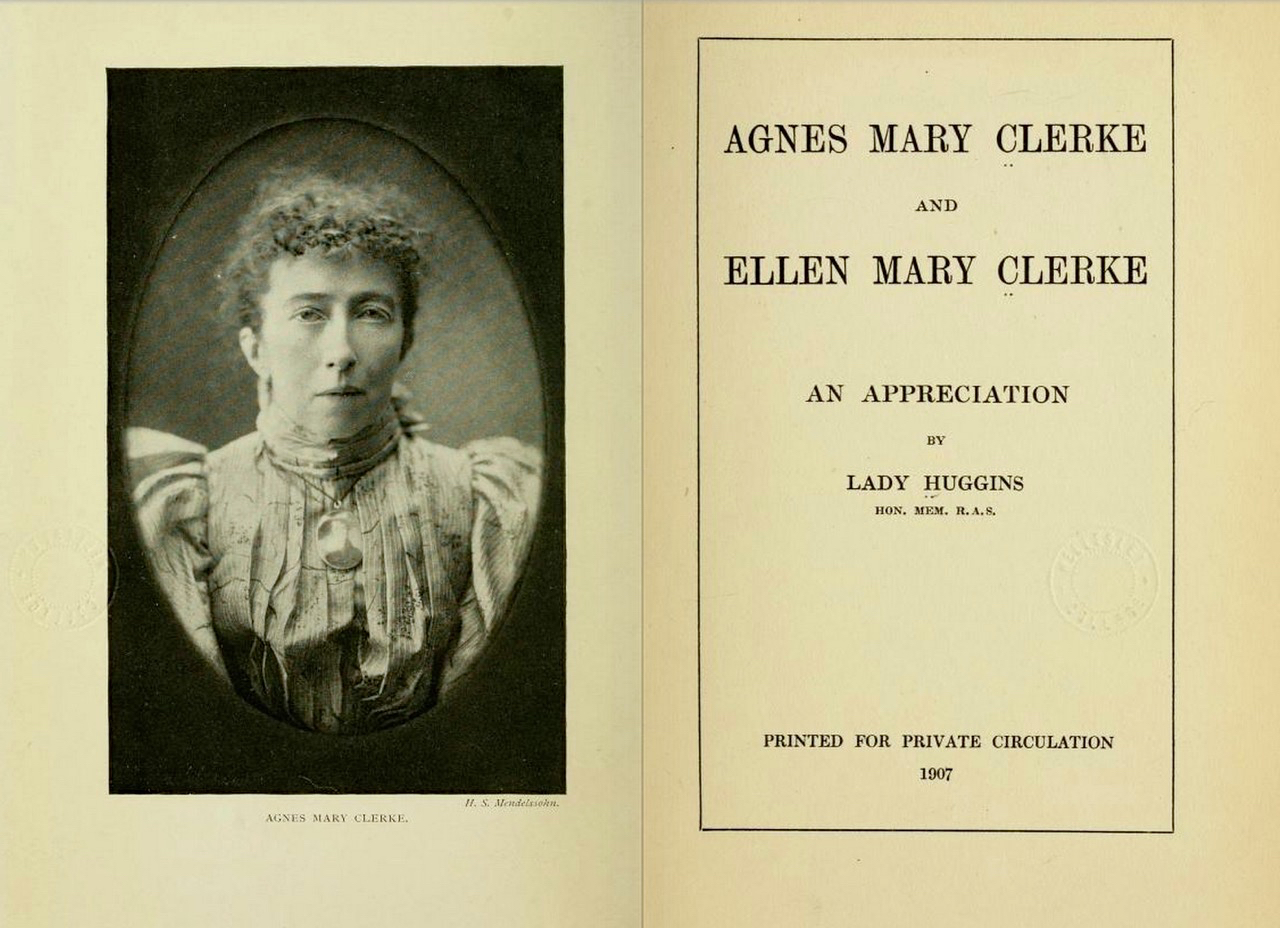

But as they read what she wrote, scientists were won over by her erudition and her ability to present their complex findings to a wide audience. Although she was a member of the British Astronomical Association, as a woman she was ineligible to be a member of the prestigious Royal Astronomical Society and had to call in favours to be allowed access to their library. But eventually even that bastion of male scientific privilege was forced to acknowledge her achievements and appointed her and her great friend Lady Margaret Huggins (another Irish astronomer, below) as honorary members. Lady Huggins was also her biographer.

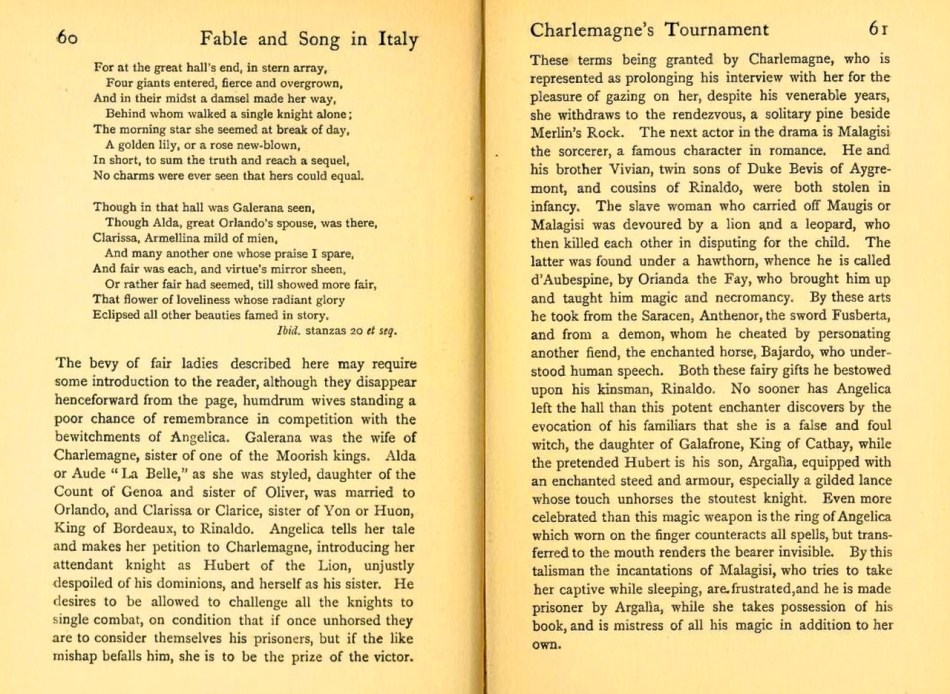

Besides her new editions of A History of Astronomy, Agnes wrote several other books on Astronomy and as a diversion took a break and wrote one about Greek Literature, Familiar Studies in Homer (she knew how to take it easy).

The foremost authority on Agnes’s life and scholarship was Mary Brück. Of Agnes, she said:

This remarkable woman, educated solely within her own family and through her own private studies, not only kept abreast of astronomical progress world-wide but also had a genuine understanding of the matters on which she reported and the gift of communicating them through her fluent and prolific writings. Her books – in particular her Popular History of Astronomy during the Nineteenth Century, first published in 1885 and reprinted over almost twenty years – are treasured by historians and by amateur lovers of astronomy alike as sources of reliable and enjoyable information on that period.

I loved her description of Agnes at the height of her powers: Agnes Clerke in her sixties had become a sort of mother figure among astronomers, tactful, kind, helpful. In one account, she was described at a scientific event surrounded by leading astronomers, genuinely keen to hear her opinion on some knotty point.

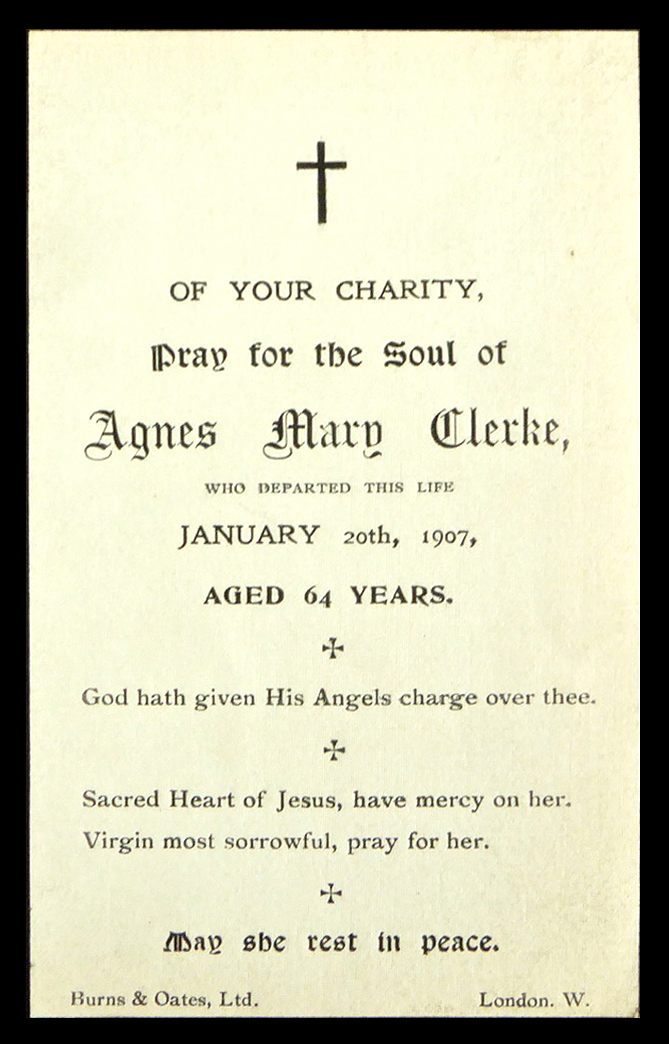

Agnes died in 1907, of the same flu that had carried off her beloved sister, Ellen, the year before. Aubrey lived on alone in the house in Redcliffe Square, the house where they had lived and worked and hosted many gatherings of eminent scientists and writers.

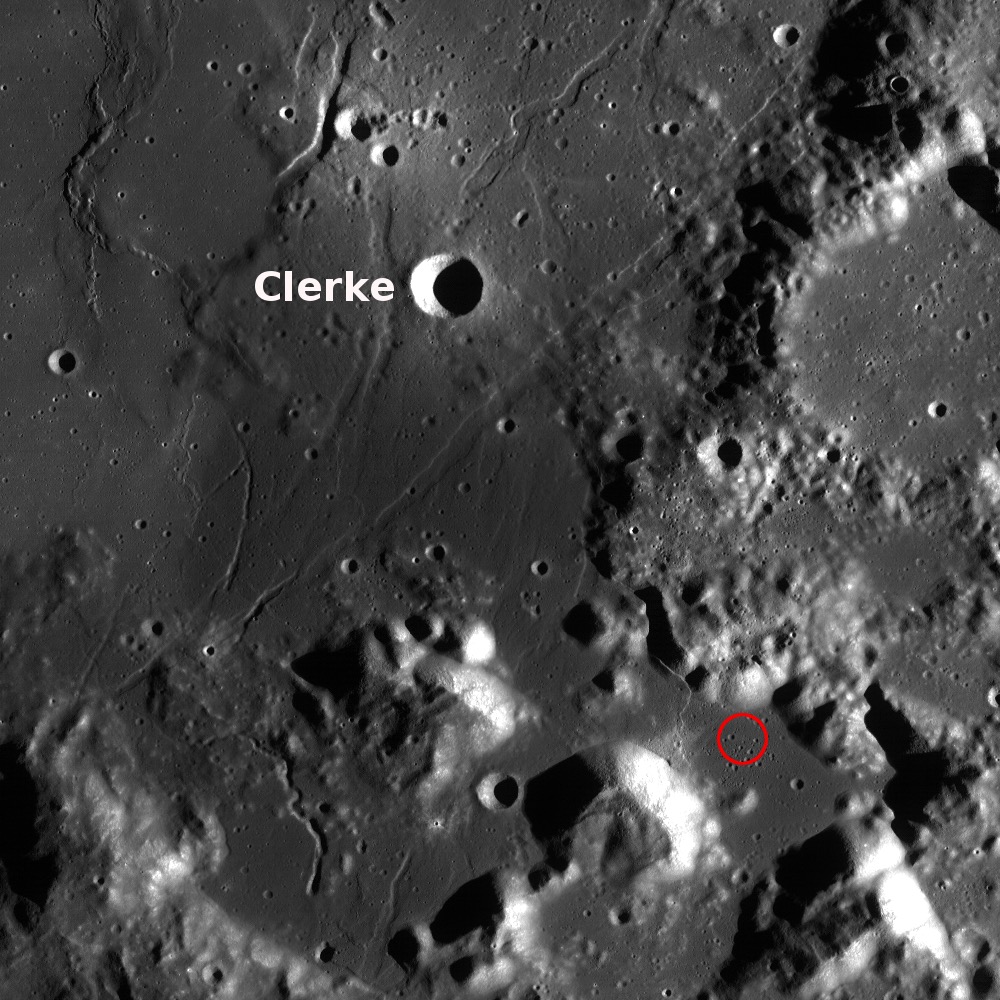

In 1981, Agnes was paid a high honour. A crater on the moon, near the Apollo 17 landing site, was named the Clerke Crater by the International Astronomical Union.

I have written about Ellen and Aubrey here. It seems apt to close this piece on Agnes with a quote from one of Ellen’s poems, Night’s Soliloquy:

…are not hidden things

Reveal’d to science when with piercing sight

She looks beneath the shadow of my wings

To fathom space and sound the infinite?

Thanks to: